3.3: The Texas Constitution Today

- Page ID

- 129148

Given that Texas went through six constitutions in a forty year period, it seems unusual that it has had the same constitution in place for almost 150 years. But this is a bit misleading. While, with few exceptions, it has retained the characteristics and principles written into it in 1876—the same basic rights and liberties, the same basic structure and internal procedures, and the same governing institutions composed of individuals directly elected by the people—significant changes have been made to the document that reflect Texas’s transition from a state where over ninety percent of the people lived on a farm or ranch. The agrarian interests of 1876 were best served by regulatory power over business, limits on spending, and local control. Expansive education and infrastructure needs, apart from transportation, were relatively limited. Today, Texas is a commercial juggernaut. It’s Gross State Product would make it the tenth largest economy in the world if it were a sovereign nation. This kind of economic growth would have been impossible had the financial restraints in the 1876 version remained in place.

The Amendment Process

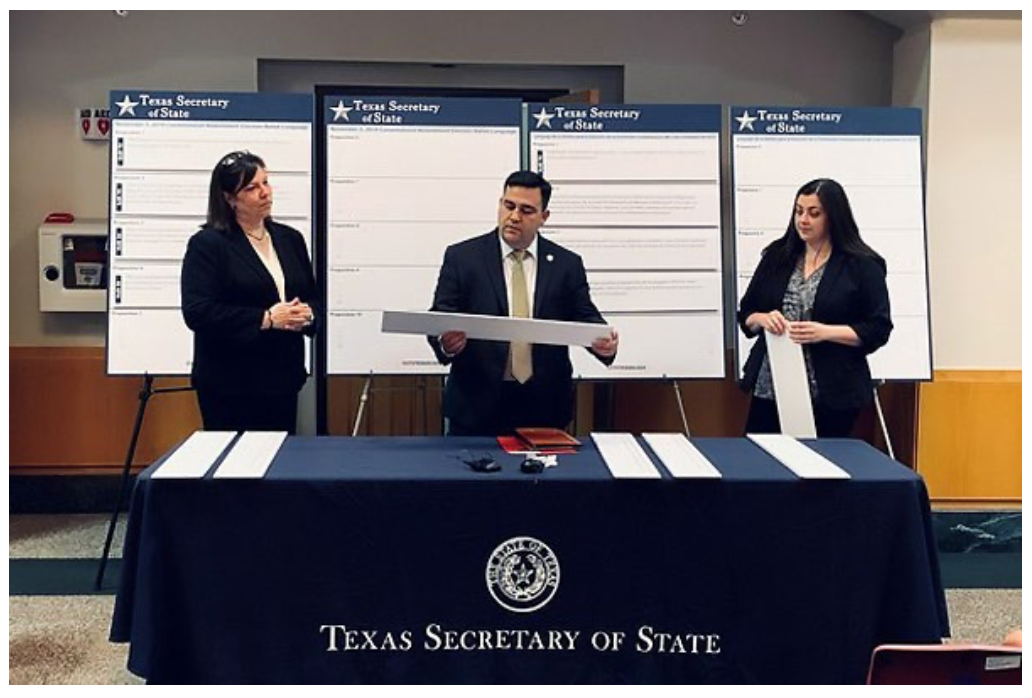

The clarity in the language in most—but not all—of the Texas Constitution makes it difficult to drive constitutional change through the Texas courts, as is done on the national level when the U.S. Supreme Court reinterprets the vague terminology of the U.S. Constitution. But the relatively low bar for changing the document itself makes the amendment process doable. A simple majority of voters must approve an amendment in Texas. Legislators propose an amendment. The Texas secretary of state drafts a ballot explanation of the amendment which must be approved by the attorney general (Figure 3.6). The ballot explanation is what the voters see on the ballot when they vote on the amendment. These must be published in newspapers that print official notices, and they must be sent to each county clerk, with explanations of the amendment. The county clerk posts this in the county courthouse. The governor plays no role in the process, a signature is not required. These amendments are often passed with legislation that then leads to the actual implementation of the desired policy.

Soon after ratification, proposals to amend the constitution became increasingly common. Some of the amendments removed parts of the original constitution, though most either added new Sections, or added new language to existing Sections. The number of amendments proposed stayed relatively low until the mid-twentieth century, however. Spikes occurred in the 1960s and 1970s, and since the mid-1980s more often than not the legislature sees the need to offer more than a dozen amendments to the public each year. Table 3.3 shows the frequency with which amendments have been approved by the voters since the first amendment was proposed in 1879.

Table 3.3 Number of Changes to the Articles of the 1876 Texas Constitution., 1879-2019

| Article | Subject | Number of Changes |

| Article 1 | Bill of Rights | +2143 |

| Article 2 | Separated Powers | no change |

| Article 3 | The Legislature | +29,127 |

| Article 4 | The Executive | +1,556 |

| Article 5 | The Judiciary | +4,616 |

| Article 6 | Suffrage | +555 |

| Article 7 | Education | +7493 |

| Article 8 | Taxation | +11,267 |

| Article 9 | Counties | +4,534 |

| Article 10 | Railroads | -551 |

| Article 11 | Municipal Corporations | +800 |

| Article 12 | Private Corporations | -174 |

| Article 13 | Spanish and Mexican Land Titles | Repealed |

| Article 14 | Public Lands and Land Office | -820 |

| Article 15 | Impeachment | +173 |

| Article 16 | Supplemental Provisions | +14,130 |

| Article 17 | Amendments | +219 |

* minus (-) and plus (+) indicate language remove or added to an Article.

The Texas Constitution has grown from 22,911 words in 1876s to 97,642 as of the constitutional election of November 5, 2019. This is the second longest state constitution. The longest is Alabama’s which contains an incredible 388,882 words as of 2019. It is the longest constitution of any type in the world, and the reason is simple. All power is centralized in the state government. Local governments have little independent power, which was set in place in the nineteenth century to perpetuate the control of the status quo. Any change in local law has to happen at the state level. Most state constitution have less than 40,000 words. The shortest is Utah’s at less than 9,000 words.

In the early years, voters were reluctant to pass amendments. In fourteen of the first thirty-seven constitutional amendment elections the voters refused to ratify any of them. In recent years it has been common for the voters to approve all, or most, of the proposed amendments. Turnout in these elections is often exceptionally low, though. It is not unusual for turnout to be less than five percent of the eligible population. Even for those voters who do vote, the language on the ballot can be confusing, vague, or misleading. For example, the amendment offered to the voters on September 13, 2003, which implemented financial limits on pain and suffering awards for malpractice simply stated:

Proposing a constitutional amendment concerning civil lawsuits against doctors and health care providers, and other actions, authorizing the legislature to determine limitations on non-economic damages.33

It did not go into any specific detail regarding the nature of those limitations. Different groups provide analyses of the readability of ballot initiatives. The title of an amendment offered in 2017 proposing tax exemptions for partially disabled veterans with donated homes was judged to require thirty-six years of formal education to understand.

Proposals to change the constitution continue. As of this writing, over 200 proposed amendments have been introduced to the Eighty-Seventh Session of the Texas Legislature. Since amendments have to be introduced to the legislature as joint resolutions, it is easy to find and follow them through the legislative process. If history is any indication, anywhere from five to twenty will pass the legislature and be presented to the voters in November of 2021. By the time you read this, some of these listed in Table 3.4 might well be in the constitution. Even those that do not succeed might be resubmitted when the legislature meets again in 2023.

Table 3.4 Amendments Proposed by the 87th Texas Legislature*

| HJR 5 |

Proposing a constitutional amendment authorizing the issuance of general obligation bonds and the dedication of bond proceeds to the Brain Institute of Texas research fund established to fund brain research in this state. |

| HJR 5 - |

Proposing a constitutional amendment authorizing the issuance of general obligation bonds and the dedication of bond proceeds to the Brain Institute of Texas research fund established to fund brain research in this state. |

| HJR 7 - |

Proposing a constitutional amendment to limit the time that a person may serve as a member of the Texas Legislature. |

| HJR 13 - |

Proposing a constitutional amendment to authorize and regulate the possession, cultivation, and sale of cannabis. |

| HJR 26 |

Proposing a constitutional amendment to authorize the operation of casino gaming in certain state coastal areas to provide additional money for residual windstorm insurance coverage and catastrophic flooding assistance in those areas and to authorize the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas to conduct casino gaming by executing a gaming compact with this state; providing for occupational licensing; authorizing fees; limiting certain taxes and fees. |

| HJR 41 |

Proposing a constitutional amendment to require the attorney general to appoint a special prosecutor to prosecute certain offenses that are committed by peace officers. |

| SJR 21 - |

Proposing a constitutional amendment providing for an annual state budget and annual legislative sessions for budget purposes. |

| SJR 24 - |

Proposing a constitutional amendment to prohibit the legislature from requiring a license or permit for the wearing of arms. |

| SJR 68 - |

Proposing a constitutional amendment exempting this state from daylight saving time. |

*Joint resolutions, such as a HJR (House Joint Resolution) and SJR (Senate Joint Resolution) are used to propose amendments to the Texas Constitution.

What Has Change and What Has Not

The following description of each Article in the Texas Constitution paints a picture of the Texas Constitution under which Texas is governed today. Understanding what has changed and what has not helps isolate the trends in order to determine what types of changes are likely to continue into the future.

Article 1 The Bill of Rights This has grown from twenty-nine Sections with 1,450 words to thirty-four Sections with 3,393 words, but while it has more than doubled in size, the additional language is concentrated in a small number of Sections. Of the twenty-nine original Sections in the Bill of Rights, twenty-three have not been changed. These include an expansive proactive declaration of religious liberty, the rights and responsibilities of free speech and the press, due process rights, the right of habeas corpus, and trial by jury. As with other states, it contains a right to keep and bear arms for the purpose of self-defense.

Section 29 deserves special attention because it declares that the rights contained in the first Article cannot be changed:

To guard against transgressions of the high powers herein delegated, we declare that everything in this "Bill of Rights" is excepted out of the general powers of government, and shall forever remain inviolate, and all laws contrary thereto, or to the following provisions, shall be void.

The additional terminology was added primarily to two preexisting Sections—on bail and eminent domain—and in five that have been added since 1876. Exceptions for bail began to be

added in 1956 and have continued thought 2007. These exceptions are for previous felony convictions, violations of terms of release, and violations involving family violence.

Section 3, which e stablished equal rights for free men, was changed to include “sex, race, color, creed, or national origin” when Texas ratified the Equal Rights Amendment (banning gender-based discrimination).

Additions include: stating the right of, and compensation for, victims of crime in 1989 and 1997 respectively; the right to access to and use of public beaches in 2009; and the right to hunt, fish, and harvest wildlife in 2015.

In 2005 Texas passed a ban on same sex marriage and prevented the state and local governments from recognizing those entered into elsewhere, but the ban was overturned when the U.S. Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015). It remains in the constitution however. Such provisions are called deadwood, and will likely be removed at some point in the future when doing so is uncontroversial.

Article 2 The Powers of Government No changes have occurred in Article 2:

The powers of the Government of the State of Texas shall be divided into three distinct departments, each of which shall be confided to a separate body of magistracy, to wit: Those which are Legislative to one; those which are Executive to another, and those which are Judicial to another; and no person, or collection of persons, being of one of these departments, shall exercise any power properly attached to either of the others, except in the instances herein expressly permitted.

Article 2 outlines the structure of government into three separate branches (executive, legislature, judiciary) with checks and balances through independent government powers.

Article 3 The Legislative Department The legislature is still bicameral and the terms have not changed. They still meet part time and are paid low wages, you can see the language setting the compensation and duration for sessions by clicking on this link to Section 24. But this Article has grown the most. From 3,811 words in fifty-eight Sections; it now has 32,938 words in sixty- seven Sections. The growth has been uneven. Twenty eight Sections remain unchanged, most involving procedural issues and basic checks and balances. Some procedures have been clarified, including the timing of the legislative process, the role of the governor in declaring items emergency matters, the process for filling vacancies and for taking record vote in each chamber, and setting salaries and the length of regular sessions. The added language has primarily been to expand the ability of the legislature to go into debt.

In 1948 an amendment was ratified allowing for the creation of a Legislative Redistricting Board after each census (Section 28), and in 1991 another was ratified creating the Texas Ethics Commission (Section 24-a) which sets salaries for legislators with the approval of the voters in a referendum. Most of the amendments regarding procedures have remained unchanged. The vast majority of the changes have been made to three Sections: 47, 48, and 49.

Section 47 concerns gambling. It originally stated that the legislature shall pass laws prohibiting lotteries and gift enterprises in the state. This reflects the social conservatism of the state, which continues to this day. Beginning in 1980, these laws began to be loosened. Bingo, charitable raffles, and lotteries—including the one run by the Texas Lottery Commission, were allowed. Betting on dog and horse racing was also allowed in licensed facilities.

Section 49 is by far the largest section in Article 3, and the entire constitution as well. As originally written, it was relatively short and simply placed limits on the amount of debt the state could carry, and what purposes allowed for debt, which included repelling invasion and suppressing insurrection. Since then it has been amended to allow for the selling of bonds, and the creation of funds for specific purposes—primarily business support and infrastructure development. Without their addition to the constitution, they would of course be unconstitutional. In the past several decades, almost 18,000 words in dozens of separate sections have been added in order to authorize these expenditures.

The process began in the 1940s—spurred by the return of soldiers from World War II to approve the creation of the Veteran’s Land Board and two dedicated funds for each: The Veteran’s Land Fund, and the Veteran’s Housing Assistance Fund. These have been followed by a large number of similar bonds and funds dealing from issues as diverse as water development projects, prison and highway construction, and rail relocation. The amendment creating the Rainy Day Fund—known as the Economic Stabilization Fund—was added to this Section (49-g) in 1988 following an oil bust. Most recently the voters approved an amendment in 2019 creating the Flood Infrastructure Fund to allow for the construction of flood control projects.

Similar expansions have been made to Section 50, which originally prohibited the lending of money by the state to a “person, association, or corporation.” This has been amended to allow for student and farm and ranch loans, as well as loans to local governments to maintain equipment.

Section 51 also had to be amended in order to receive and redistribute federal matching grants for assistance to needy persons.

Nine sections have been added, three of which deserve special note: these are Sections 62, 66, and 67. The first amendment was ratified in 1962, and modified in 1983 during the height of the Cold War and the fear that enemy attack (including nuclear) could eradicate the governments in Washington D.C. as well as Austin. The section created a process for the continuity of state and local government should such an attack occur.

Section 66 limits the financial liability for non-economic—or punitive—damages in a civil trial. The amendment on malpractice awards is discussed earlier in this chapter. This amendment changed the financial liability in the healthcare industry. Members of the medical profession, and the manufacturing industry, promoted its passage, as Texas juries had a tendency to be very generous in awarding large settlements to victims of negligence.

The final section in Article 3, Section 67, was originally added in 2007 and was amended in 2019. In an effort to increase the ability of the state to be a center of cancer research, and reap the rewards of the development of cures for it, voters approved the selling of up to three billion dollars in bonds to create and fund the Cancer Prevention Institute of Texas. In 2019, voters approved an additional three billion dollars.

Article 4 The Executive Department This has been changed slightly since 1876. Article 4 has 1,556 additional words, which brings it to 4,272 total, but it remains at 26 sections. Eleven of these remain unchanged. As with the legislature, the basic procedures, primarily regarding elections, relations with the legislature and the bill making process, remain the same. Doing so allowed for an expansion of power, which was deemed necessary to regulate economic affairs within the state.

The executive power remains split into separately elected offices, though these have changed slightly as the position of treasurer was eliminated in 1995. In 1907 the legislature also created the office of the commissioner of agriculture.

The role of the governor in terms of the legislature is largely unchanged, including the power the office has over special sessions. A major rollback in the governor’s power to issue pardons and paroles occurred in 1936 following allegations that Governor James Ferguson accepted bribes in the mid-1920s to issue over 3,500 pardons. An amendment was added allowing for the creation of the Board of Pardons and Paroles which was charged with making recommendations for reprieves, commutations, and pardons. The governor was limited to doing so only in cases of Treason.

While the governor’s office remains weak, especially in comparison to those in other states that have a unitary executive that appoints all other executive officials, subtle changes have been made to increase the power of the governor. Key among them was the 1972 amendment that expanded the governor’s term, along with all other elected executive officers from two to four year terms. They run for office in midterm elections, meaning elections where the president is not on the ballot.

Article 5 The Judicial Department This article created the judiciary, and it grew from twenty-eight Sections and 4,008 words to thirty-two Sections and 8,624 words. It has changed considerably since 1876. Only two Sections have not been amended (10 and 24). The additional language concerned two principal changes.

The first occurred in 1891 when thirteen separate amendments were added to the document. Collectively they were referred to as Texas Appellate Court Reorganization, and it was meant to correct what became a flaw in the design of the original court system, as well as facilitate the larger number, and variety of cases that came to the court as the state was changing. Texas has always had a system with two top courts, but it did not have an intermediate level of appellate courts until created by these amendments. Initially it had three districts and was expanded to fourteen by 1980. The Court of Appeals was renamed the Court of Criminal Appeals. Beginning In 1948 a series of amendments established an age of retirement and in 1965 a State Commission on Judicial Conduct which is charged with investigating judicial misconduct and removing judges if deemed appropriate.

Article 6 Suffrage The power to determine who could vote was fully vested in the states until after the Civil War. It continues to be an area of conflict between the national government and states like Texas since the national government has been used to expand voting rights over the resistance of those states. It still contains five Sections, and has been roughly doubled in size to just under 1000 words. The only section unchanged protects voters from arrest going to and returning from the polls. The rest have been changed slightly, but significantly, as Texas’s history has placed it under the watch of the national government in regards to voting rights and practices. Many of the changes made to this section had less to do with the desires of the state and more to do with pressures placed on it from the national government.

Changes have been made to the classes of people not allowed to vote and language has been added to cover voter registration. Changes to voter eligibility included reducing the eligible age from twenty-one to eighteen, and replacing restrictions to “idiots and lunatics” to those “determined mentally incompetent by a court.” Two restrictions were removed, these are “paupers supported by any county,” and “All soldiers, marines and seamen, employed in the service of the army or navy of the United States.” After modifications in 1932 and 1954, the later was the subject of a 1965 United States Supreme Court decision, Carrington v. Rash. Texas attempted to restrict members of the armed forces residing in the state to only vote in the counties they resided in when they joined the service. The Supreme Court argued that this was a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

Section 2, on voter requirements, was added in 1896. Even if you are eligible to vote, you do not become qualified to vote unless you are registered according to the rules established by the legislature. These were made applicable to presidential elections in a separate amendment in 1966. This proved to be an alternative way for the state to suppress voter turnout, without making it illegal. In 1902 Section 2 was amended to include the poll tax (fees charged for voting), which would be repealed in 1966 after the Twenty-Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution made them unconstitutional. At this time, in 1903, the state legislature also passed the Terrell Election Law allowing race-based voter restrictions in primary elections, another method at the time of suppressing the vote. Until 1921, the constitution allowed for non-citizens to vote if they intended to become citizens within six months. This was changed in 1921 when voters passed an amendment stating that only native born or naturalized citizen could vote. Article 7 Education—The Public Free Schools This grew from fifteen to twenty Sections and from 1414 words to 8,907. This is a significate increase of almost 7,500 words. Five Articles remain unchanged. These include the introductory Section stating the duty of the legislature to support and maintain an “efficient system of public free schools.”

Aside from providing the basic rules regarding curriculum and textbooks, the state’s role in education is primarily financial. This includes authorizing local government to add their own funding as well. Most of the content of the original article involved how funds would be drawn from public lands and placed into various funding streams. The bulk of the changes made have clarified the nature of that funding, which includes establishing the Permanent School Fund, the Available School Fund, the Permanent University Fund, the Higher Education Assistance Fund, the Available University Fund, the Texas Tomorrow Fund, and the National Research University Fund. In the 1960s, conditions were placed on the nature of the taxes that could be collected by independent school districts, and junior college districts, the authorization of which had already been established.

In 1969, Section 7 was repealed. It stated that separate school had to be provided for White and colored children. Similarly, the legislature was to—when practicable—create a college or university branch for “the colored youths of the state.” As amended, this became Prairie View A&M University as a branch of Texas A&M University.

Article 8 Taxation and Revenue Allowances for taxes had been part of the original version of Article 8 and taxes, were limited in order to keep tax rates low in the state. Economic forces were in motion, however, that would seek to make it more conducive to the interests of both industry and the urban areas that supported them, so this section has grown considerably. As the state has expanded and become more complex, issues related to funding have become more controversial and increasingly confrontational. From eighteen Sections and 1,326 words, it now has twenty-nine Sections and 12,593 words. Five Sections remain unchanged, these focus on the basic ability of the state to tax individuals and corporations, that taxes are to be by general laws and for public purposes, the inability of the state to release individuals from payment of taxes— expect “in case of great public calamity,”34 and the requirement that all property to be assessed for purposes of taxation. The explanation for the growth in language is simple. The original language was necessary to place limits on the taxing authority of both the state and local governments, loosening tight limits on state and local spending as they made the development of infrastructure difficult.

Section 1 of the original constitution allowed the legislature the right to pass laws imposing a variety of taxes. Since 1876 over a dozen subsections and approximately 7000 words have been added limiting that power, including establishing homestead exemptions, limitations on the assessment of property, and exemptions of property used in manufacturing, farming, pollution control, and water conservation. This Section also contains exemptions for items

related to commercial enterprises and activities the state wishes to promote. Recent examples include an exemption for taxing raw cocoa and green coffee beans in 2001 and rural economic development.

As the constitution authorizes local governments to collect property taxes, and as local needs have expanded, measures have been added to place limits on increases in local property taxes and who is required to pay them. Ninety amendments to this section have proven to be an efficient way to place overall limits on taxes. This also applies to the spending side, as Section 22 contains limits on the increase of spending in the state.

Article 9 Counties and Article 11 Municipal Corporations These original Articles were quite small. Article 9 contained two Sections and 472 words; Article 11 had ten Sections and 815 words. The original sections in Article 9 gave the legislature the power to create counties, placed limits on their minimum size, and protected the borders of existing counties. The second placed limits on the ability of the legislature to remove county seats. There is mention that county seats should be within five miles of the geographic center of the county. This is important because the county seat is where residents can conduct business with the state. A rule of thumb from the day was that people should be no further than one day’s travel from the county seat.

Over the years twelve Sections and over 4,500 words have been added to Article 9, and three Sections and 800 words have been added to Article 11. The content of Article 11 covers counties as well as cities. It begins by defining counties as legal subdivisions of the state and gives the state the authority to pass laws regarding the construction of “jails, court-houses, and bridges” and “the laying out, construction and repairing of county roads.” The increase in railroad transportation fueled boost in manufacturing, and the increase of manufacturing led to the growth of urban areas. As cities grew, their residents sought greater autonomy, as well as resources. In 1909 and 1912 Section 5 was amended to allow cities greater autonomy in conducting their own affairs. Larger cities were granted home-rule status, which expanded their ability to pass laws as they saw fit, and the ability of counties to tax their residents to construct roads and bridges, and to create special districts for emergency services, among other services demanded by their residents.

Article 10 Railroads, Article 12 Private Corporations, and Article 14 Public Lands Three Articles have been reduced in size. All concern the regulation of business, which could be heavily regulated according to the original constitution. In the late nineteenth century, the state was subject to the power of out of state corporate interests, particularly railroads and monopolies. These were rife with corruption and abuse, which led to a need to control banking and railroad companies in particular. Economic forces, however, were in motion that would seek to transform the document to make it more conducive to the interests of industry. Key restrictions that would be whittled away were business regulations that were written into the original constitution and the tight limits on state and local spending that made the development of infrastructure difficult.

Article 10 contained nine Sections touching on a variety of aspects of business, including limits on ownership and the discretion railroad companies had in where they laid their tracks. This has since been reduced to one Section—Section 2—declaring railroads to be common carriers. You can see the changes yourself by clicking on the original language of Article 10 here, and its current language here. This makes then subject to regulation to, among other things, “correct abuses and prevent unjust discrimination and extortion” in the rates charged. The term common carrier is important because it refers to a person or company that offers to transport items for the public. These can be physical items or non-physical like text and voice messages and data, as can oil and gas pipelines. As common carriers they can be regulated in the public interest.

Article 12 has been reduced to only stating they can only be created by laws passed by the legislature, and these laws shall protect the public and individual stockholders.

Article 14 was reduced to the single section establishing the land office, declaring that all land titles be registered with it, and that the office be self-sustaining. Sections which had limits on grants to railroad companies, and guaranteed homesteads to qualified individuals—heads of households and single males over eighteen—were removed. Sections related to resolving disputes over land ownership were removed following the ultimate resolution of these claims.

Article 13 Spanish and Mexican Land Titles Article 13 was completely removed in 1969 because there were no outstanding disputes that needed resolution.

Article 15 Impeachment Article 15 has not changed substantively since 1876. The process is similar to that on the national level. Members of the plural executive and all state judges, including district court judges, are subject to removal from office based on a simple majority vote to impeach in the House of Representatives, followed by a two-thirds vote to remove from office in the Senate. As opposed to the U.S. Constitution, there is no clear statement regarding why an official can be impeached, nothing similar to the high crimes and misdemeanors standards. Only two officials have been impeached and removed from office in Texas history. Political conflicts between Governor James Ferguson and the University of Texas—which culminated in Ferguson’s use of the line item veto to remove all appropriations to the university—led to his impeachment in 1917. He was also accused of embezzlement and misappropriation of public funds. In 1975, District Judge O.P. Carrillo was impeached and removed from office following a conviction on income tax charges.

Article 16: General Provisions This section contains items that were judged to not fit neatly anywhere else in the constitution. This includes the surviving aspects of Spanish law, specifically Section 15 which establishes communal property for spouses and Section 50, which concerns homestead protection. It has been amended greatly. In 1997 Section 50 was altered, controversially, to allow for reverse mortgages, meaning that people could borrow money against the equity they have built up in their homes. Language was inserted in order to ensure that borrowers understood the risks they were taking since failure to pay back the mortgage can result in the loss of the home.

Section 16 contained prohibitions on banking, and can be used as an example of the changes in the document related to the increased power of businesses in the state. Beginning in 1904, a series of amendments were added allowing the legislature to pass laws incorporating state banks and savings and loans. These provisions are contained in Section 16. Overtime these allowances have been expanded in order to facilitate the expansion of the financial sector in the state.

Section 20 allows for the legislature to pass laws related to alcohol, including the creation of a state monopoly on the sale of distilled liquors. The industry is divided into brewers and distillers, distributors, and sellers. This arrangement benefits enough of the industry that the three-part regulatory system has been maintained over the objection of smaller interests— notably brewers—which would like to be able to sell their product directly, as the wine industry has been allowed to do since 2003. Local areas are still permitted to have local option elections to determine what can and cannot be sold in the state.

Article 17 Amendments The amendment process, discussed previously in the chapter, is detailed in Article 17. Fittingly, it is the last Article of the Texas Constitution.

33. HJR 3, https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/78...l/HJ00003F.htm.

34. Tex. Const. art. VIII, § 10, https://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/const...xation-revenue.