4.2: A History of Political Parties in Texas

- Page ID

- 129153

The Democratic and Republican Parties have not always existed. When George Washington became the country’s first president, there were no parties. But parties began to form around the issue of how powerful the new federal government should be. Federalists favored a strong central government. The Democratic-Republican Party did not. The National Republican Party replaced the Democratic-Republican Party in 1824, primarily in opposition to Andrew Jackson. Andrew Jackson then founded the Democratic Party we know today in 1826 and ran for president. The Whigs replaced the National Republican Party in 1833, again, primarily in opposition to Andrew Jackson. The Republican Party we know today, founded in 1854, grew out of the anti-slavery faction of the Whig Party. Not only can party names change, but what policies and values a party represents can change, too (Figure 4.3). The Democratic Party once supported slavery but today fights against racial discrimination. The Republican Party dominates the South, fighting to maintain traditional norms.

Beginnings

Texas had no organized political parties before joining the Union in 1845. In the early days of settlement, those who came to Texas were happy to leave government and politics behind. Since there was no strong party tradition in the Republic of Texas, elections held after the state gained its independence in 1836 primarily reflected support for individual candidates.3

During the period of the Texas Republic (1836–1845), Texas politics was dominated by Sam Houston, the hero of the war for independence from Mexico. Although there were no political parties, pro-Houston and anti-Houston factions existed.4

However, the majority of early settlers came from the South and brought their past political allegiances to Andrew Jackson’s Democratic Party with them. The state’s fledgling Democratic Party evolved over the years from a very loose association of merchants, doctors, lawyers, and other professionals into an organized, unified party without any legitimate opposition. Nationally, the Democrats were pro-slavery, while their opponents, the Whigs, were divided on the issue. Designed largely to challenge the Jacksonian Democrats, the Whigs were a diverse group comprised of people who supported a variety of issues, such as moral reform, opposition to the harsh treatment of American Indians, and the abolition of slavery. The Democrats had also endorsed the admission of Texas to the Union during the 1844 presidential campaign, whereas the Whigs had waffled on the issue. Texas became a state in 1845 as a slave state, with most Texans supporting Democrats.5 Even so, it was some time before Democrats adopted any sort of a statewide network or arranged for scheduled conventions. Contests between rival factions evolved into a more defined stage of competition with the development of the Democratic Party in Texas as a formal organ of the electoral process during the 1848 presidential contest among three candidates: Whig Zachary Taylor, a war hero in the Mexican- American War who wanted to preserve the Union; pro-slavery Democrat Lewis Cass; and anti- slavery Martin van Buren, of the Free Soil Party. Taylor won the election, but the firestorm around slavery would not be quenched.

Beginning in the 1850s, the Democratic Party was solidly aligned with the pro-slavery, wing of the national party, and factionalism in the party essentially ceased.6 Texas, despite opposition by Sam Houston and others, seceded from the Union and joined the Confederacy in 1861. The North, led by the Republican administration of Abraham Lincoln, defeated the Confederacy and officially freed those who had been enslaved. Under the aegis of the Congressional Reconstruction Act of 1867, Union troops then occupied the former Confederate states to ensure the rights of freedmen and women were recognized,

During Reconstruction (1863 to 1877), the divisions between Unionist and Secessionist Democrats once again became intense and more pronounced, Former Confederates found themselves under the rule of northerners, the military, and—even worse for most—newly freed African Americans who now assumed leadership roles in the military and the postwar government.7 It was also during Reconstruction that the state saw the creation of the Republican Party in Texas. African Americans emerged as a new group of voters who consistently supported the Republican Party. In fact, because former Confederates were required to take an Ironclad Oath (an oath that they would never bear arms against the Union or support the Confederacy) in order to regain their right to vote, ninety percent of the Republican Party’s members were African American. Despite the strong support of African Americans and groups that had opposed slavery and secession (such as the Northern Methodists of Texas whose Reverend Anthony Bewley was lynched for his belief and Bexar County’s German Texans who were massacred by Confederate soldiers at the Battle of Nueces in 1862), the Reconstruction period was troublesome at best for the new Republican Party.8

Many former Confederates chafed under what they believed were the dictatorial and vindictive policies of the Congressional Reconstruction Act, and the Reconstruction period was troublesome at best for the new Republican Party. Edmund J. Davis, a Unionist and a Republican, became governor in 1870, and his four-year administration was marked with bitter controversy, voter suppression, scandal, corruption, and oppression.9 Ultimately, Davis and the Republican Party prompted a profound response in Texas by those who believed they were subjected to the tyranny and despotism of a foreign conqueror identified with the Republican Party. Democrats captured the Texas legislature in 1872, and in the 1873 gubernatorial election Democrat Richard Coke, a judge and former Confederate who had fought as captain of the Fifteenth Texas Infantry, easily defeated Davis.10

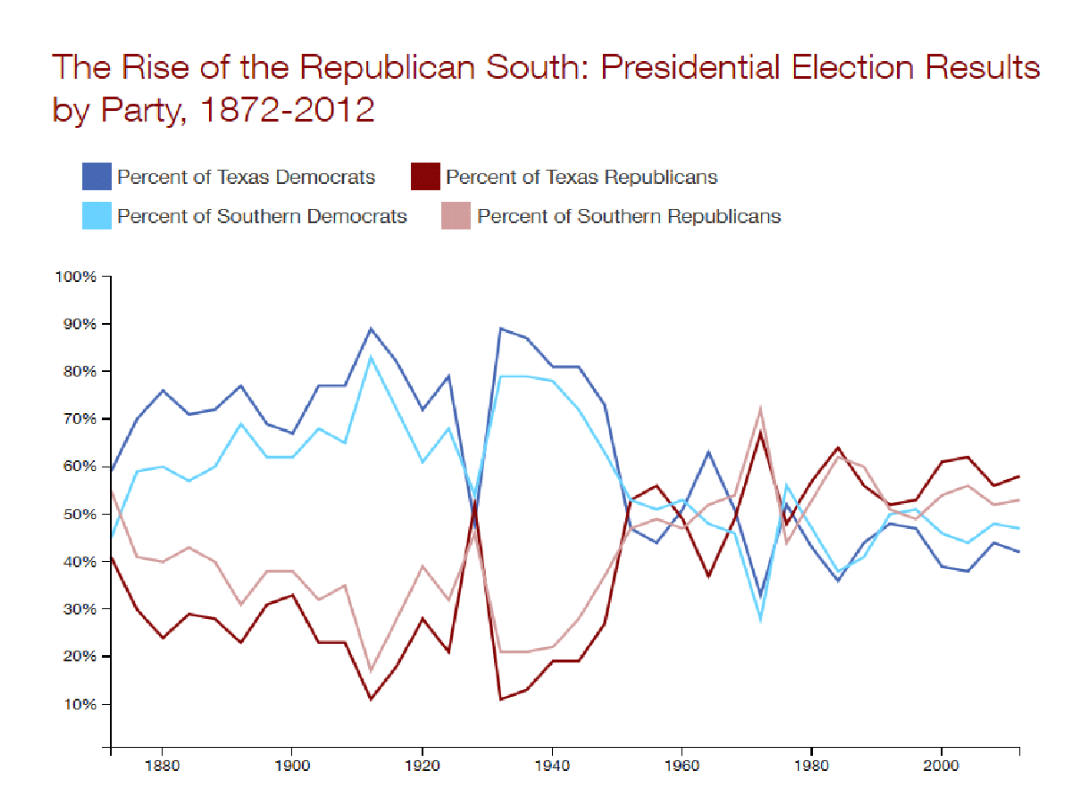

The Democratic Party and a One-Party State

In this crucible, Texas politics for the next century was forged. The Democratic Party became the vehicle of southern resistance to northern domination and of White opposition to the granting and exercise of full citizenship rights for African Americans, particularly voting rights.11 The final Democratic measure to overturn all Republican influence in Texas came with the ratification of the Constitution of 1876, which reversed most of the acts and effects of the Davis regime.12 As a result, when Reconstruction ended in 1877, Texas—like the other former members of the Confederacy—was a solid one-party state with the Democratic Party in power.13 For the next century, the Republican Party was not a viable force in Texas politics. The agrarian Grange movement had more influence in its efforts to protect farmers who had been crushed by devastated crop prices and the erratic transportation fees charged by railroads during the financial panic of 1873. Their People’s Party was one of the most successful of the historic Third Parties discussed earlier in this chapter and their reforms became part of policies promoted by the Democratic Party, including the creation of the Railroad Commission to regulate price gouging. While the Grange movement had its successes during that period, the Republican Party failed to win a single statewide race and controlled only a handful of seats in the legislature.14 One-party Democratic control remained the norm until the late 1960s, with telling effects on politics and public policy (Figure 4.4).15

It is often difficult for younger White Texans to understand the animosity that their White ancestors held for Republicans who governed the state during Reconstruction. Virtually no Republicans ran for statewide office for decades since doing so would have been futile. For the most part, it was politically impossible for any Republican to win elective office in the state. Because there was, for around 100 years, no loyal opposition to Democrats in Texas, the general election was essentially decided in Democratic Party primaries (elections in which candidates from the same party are seek the majority of the vote cast by members of the public who demonstrate their preferences only for their party’s candidates). As a result, nominees from the Democratic Party usually ran unopposed in the general election.16

While a candidate’s party label was (and, in many cases still is) the most important guide for an American voter in national elections, it was of little or no value in Texas. The state’s voters usually had a choice between several candidates for each office, but they were all Democrats. Only limited debate on public policy was exchanged between liberal and conservative Democrats. Without party competition to foster more vigorous debate about the most critical state issues or to spur voter interest, most White citizens were apathetic, and voter turnout was very low. Be mindful that despite the fact that African Americans were granted the right to more actively participate in politics, they were often not able to freely exercise those rights because of the number of political obstacles placed in their path, including intimidation that included violence and lynching by the Ku Klux Klan.

The return to power of the Democratic Party did not resolve the stark differences between the competing factions within the party, however.17 Interestingly, during this period, candidates of all ideological persuasions, including liberals, conservatives, members of the Ku Klux Klan, and those who ran on single-issues (like Prohibition), all ran as Democrats.18

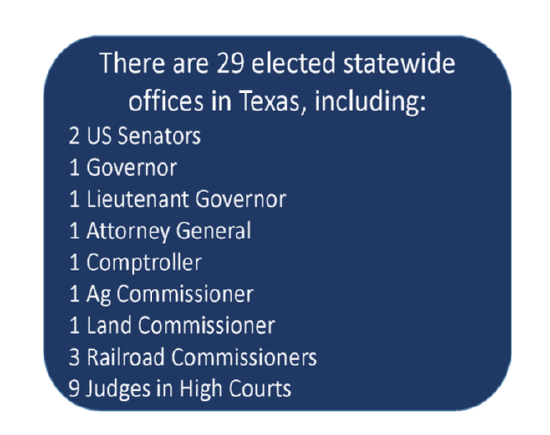

Traditional party functions such as recruiting, financing, and conducting campaigns were performed not by the party but by informal, unofficial organizations, campaign committees, and other groups. Voters were generally uninformed about these groups and knew little, if anything, about who controlled the parties or their agendas. Consequently, when voters elected only Democrats to the officers of governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general, comptroller, and other offices (Figure 4.5), they were not electing a Democratic “team” to govern in Austin. Rather, they were electing independent officials who were frequently political rivals and shared little except personal ambition and the Democratic label. The parties acted to emphasize, not overcome, the limited government created by the state constitution,19 as the Texas Constitution limits the role of the governor by fragmenting power in the executive branch, dividing the power traditionally vested in the governor amongst other government officials. The term plural executive describes this fragmented power.

Under the conditions of splintered power, because there was no unified team, there was no universally accepted or created public policy. Each politician pursued his or her own interests and those of their constituencies. In other words, one-party politics in Texas was really no-party politics. Instead of vigorous debate and citizen involvement that characterize well-run democracies, confusion and apathy reigned in the midst of this lengthy, one-party dominance.20 Conservative vs. Progressive Democratic Factions

The transition to two-party politics in Texas changed this dysfunctional system, but that change occurred slowly and intermittently.21 The decade of the 1920s was a bridge for Democrats between the reforms of the Progressive Era—such as child labor, workers’ compensation, the eight-hour work day, regulating monopolies and railroads, safe food, drug, and housing standards, among many others, including, as mentioned earlier in this chapter, minimum wage and women’s suffrage—and the economic collapse of the Great Depression. Southern Democrats, including Texas Democrats, shifted their goals for reform from social issues toward business and economic growth, government efficiency, and governmental support for educational and prison reform, as well as highway and industrial construction.22

Beginning in 1928, in the midst of a bitter feud between the warring factions of the Democratic Party about such issues as the legitimacy of the Ku Klux Klan and Prohibition, Texas occasionally voted for Republican presidential candidates. Still, the party held complete control of state politics and government. From the mid-1930s until the early 1950s, the Democratic Party experienced significant upheaval as a result of inter-party disputes between its conservative and liberal factions relating to the issues of oil and gas regulation, the severe economic impact of the Great Depression, the New Deal legislation ushered in by the election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt as president in 1933, and the prevention or limitation of African American voting rights.23 Still, Democrats were staunchly loyal to the party even with divides over government programs and civil rights. These old school Democrats were known as yellow dog Democrats, so called because of the nineteenth century saying, “I’d vote for a yellow dog if he ran on the Democratic ticket.”24 A conservative blue dog Democrat, on the other hand, would become Republican.25 It is widely believed that the Republican Party officially entered the modern era of state politics in the mid-1940s, while Democrats were fighting amongst themselves.26

No one anticipated that the Democratic Party would politically implode in the 1950s and, in the process, provide an almost forgotten Republican Party the opportunity to gain inroads to statewide and national political power. The Democrats three primary factions—conservatives (otherwise known as the Shivercrats, for Democratic governor Allan Shivers, who backed Republican Dwight Eisenhower for president), moderates (who backed the policies espoused by then Senator Lyndon B. Johnson), and liberals. who backed Adlai Stevenson, the Democratic nominee. These three cliques engaged in an “intraparty battle that featured mistrust, mudslinging, shifting alliances, and ultimately a deeper division within the party.”27

In 1961, Republican John Tower cracked the Democratic monopoly at the state level by winning a special election for a U.S. Senate seat vacated by Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson.28 Tower had campaigned for the popular Dwight Eisenhower in Texas and was supported by the former governor of the state, conservative Democrat Coke Stevenson (named for Governor Richard Coke mentioned earlier in the chapter). He campaigned heavily for “independent- thinking” in courting the conservative Democrat vote.29 Liberal Democrats refused to vote for Tower’s opponent, William Blakley, another “Eisenhower Democrat” whom they found too conservative.30 Tower won, and from 1964 until 1978, Republicans gradually won more local elections in Dallas and Houston and experienced slow, but growing success electing candidates to the federal and state House of Representatives and Senate.31 However, conservative Democrats continued to dominate state politics well into the 1970s despite the electoral losses of some of their most well-known and respective candidates.32

In 1978, the state’s first Republican governor in 104 years—William P. Clements—was elected, but he did not win reelection in 1982. Despite his loss for reelection, it was clear that the party has arrived and intended to stay as a critical player in the state’s political landscape.29 Experts rightfully contend that the party’s reemergence was attributable to the vast number of moderate and conservative Democrats who abandoned their party loyalty to support conservative Republican candidates (Figure 4.6).30

Republican Realignment and a New One-Party Regime

President Ronald Reagan’s landslide reelection in 1984 finally broke the Democrats’ stronghold on Texas. Dozens of Republican candidates gladly rode Reagan’s political coattails to victory in state and local elections. Some of the local officeholders subsequently loss their reelection bids, but by then, Texas was no longer Democratic.31 Any doubts about Republican realignment—a change in the partisan identification or affiliation resulting in a standing decision to vote for a given party—in Texas were removed in the 1986 election cycle. By then, the majority of “old school” conservative Democrats had either fled their party or retired from office..32 As a result, aside from rare exceptions, the only Democrats left in the party were liberal.33

Former Governor William Clements was reelected by a wide margin in 1990, and his party enjoyed gains in all three branches of the state government and also in the federal government. The 1994 elections were truly a watershed for Republicans, who defeated an incumbent Democratic governor (Ann Richards), garnered the state’s second U.S. Senate seat, pulled nearly even with Democrats in the number of state senators, and saw hundreds of local offices won by their candidates. In 1994 Republican George W. Bush won the governorship and since then no Democrat has won state office. Two years later, Republicans won the majority in the Texas Senate, the first time the party had been able to achieve this feat since Reconstruction. And in 1998, Republicans swept the statewide races.34

In 2003, Republicans gained additional seats in the Texas Senate and, for the first time in 130 years, a majority in the Texas House of Representatives.34 By 2006, Texas could just barely be considered a two-party state. Every statewide elective official, including all eighteen members of the two highest courts, was a Republican, as were both U.S. senators and the majorities in both chambers of the Texas legislature. Texas has decisively voted for Republican presidential candidates since 1980. The last Democratic bastion—the party’s slim majority in the state’s delegation to the U.S. House of Representatives—fell as a result of the Republican Party’s 2003 redistricting bill.36

Let’s Have a Tea Party!

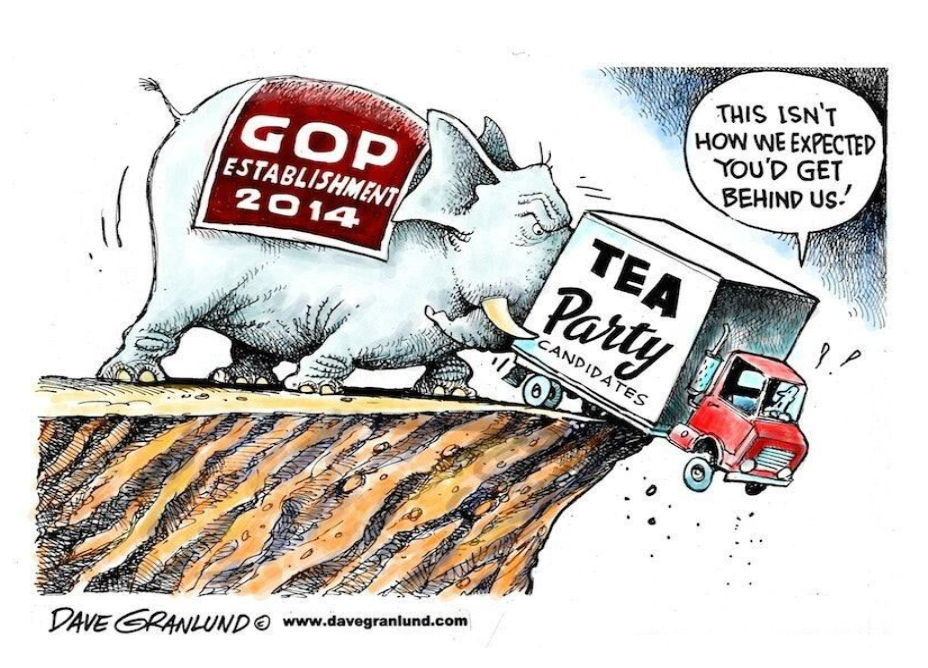

Tea and crumpets anyone? It sounds like something from Alice in Wonderland—tea with the Mad Hatter—but no, the Tea Party is a grassroots movement within the Republican Party by those who felt Republicans were not being Republican enough. Perhaps the Tea Party movement took hold within Texas because, lacking any real opposition from the Democratic Party, the Republican Party felt the need to create competition within itself. There are those whom The Tea Party labeled RINOS—Republicans In Name Only—whom they felt were not true enough to the party’s conservative values and some in the party don’t appreciate the label or the competition (Figure 4.7). The intra-party divide occurred in the mid-2000s as backlash against the election in 2008 of Barack Obama to the presidency of the United States. Many were unhappy with the programs initiated by then-President Obama, particularly the Affordable Care Act, dubbed Obamacare, which required everyone to purchase medical insurance to support government subsidies for insurance companies that agreed to provide care. The price of the insurance was then scaled to the individual’s income. The rollout of the program through State- based Exchanges was confusing and the various levels of insurance (bronze to gold) often had steep premium increases. The requirement to purchase insurance was repealed in 2017, though the program is still in effect.

The Tea Party name came from the Boston Tea Party, where colonists threw tea into Boston harbor to protest British taxes. The Tea Party actually began in Texas, created by U.S. House Republican Texan Dick Armey. Although the movement went on to gain national support, everything is bigger in Texas including Tea Party support. Republicans like U.S. Senator Ted Cruz and Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick rode the wave of Tea Party support to victory. Since Obama left office, the Tea Party has evolved into the Freedom Caucus, which continues to wield tremendous support in the Republican Party, although not the support it once had. Many representatives and statewide officials are beholden to its support, including U.S. Representatives Louie Gohmert, and Representative Michael C. Burgess, Attorney General Ken Paxton, Senator Ted Cruz, and many others.

A Two-Party State? Demographic Changes and Shifting Voting Patterns

Until the 1980s, enough Texans had adopted a standing decision to vote for candidates of the Democratic Party, whose candidates could win most of the time. By the twenty-first century, however, enough Texans had changed their affiliations so that Republicans were normally victorious in statewide, although not necessarily in local, elections. Once a solidly Democratic state, Texas has aligned to be overwhelmingly Republican. If voting trends of the past two decades had continued, Texas might have become as much a one-party state deep into the twenty-first century as it was in the twentieth century, but with a different party in command. However, that now seems unlikely. The voting and survey date collected during the last two decades of the twentieth century indicate that Texas has experienced another realignment. Demographic changes and shifting voting patterns in the state has led to the reemergence of the Democratic Party in state legislative, local, and some judicial races.37

The resumption of two-party competition in Texas will undoubtedly prove beneficial for democracy in the state. In recent years, there has once again been robust debate between the two major parties on many issues important to citizens.

3. Nancy Beck Young, “Democratic Party,” Texas Historical Association, Handbook of Texas, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/...mocratic-party.

4. Kenneth Dautrich, David A. Yalof, David F. Prindle, Charldean Newell, and Mark Shomaker,. American Government: Historical, Popular, and Global Perspectives: Texas Edition (Belmont: Wadsworth, 2009).

5. Dautrich. et al., American Government: Texas Edition.

6. Young, “Democratic Party,” https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/...mocratic-party.

7. Dautrich, et al., American Government: Texas Edition.

8. Claude Elliot, “Abolition,” Texas State Historical Association Handbook of Texas, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/abolition; Donald E. Reynolds, “Anthony Bewley (1804-1860),” Texas State Historical Association Handbook of Texas, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/...bewley-anthony.

9. “Overview and History,” Republican Party of Texas, https://www.texasgop.org/overview-and-history/.

10. Carl H. Moneyhon, “Republican Party,” Texas State Historical Association Handbook of Texas, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/...publican-party.

11. Dautrich, et al., American Government: Texas Edition.

12. Young, “Democratic Party,” https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/...mocratic-party.

13. Dautrich, et al., American Government: Texas Edition.

14. “Overview and History,” Republican Party of Texas, https://www.texasgop.org/overview- and-history/.

15. Dautrich, et al., American Government: Texas Edition.

16. Dautrich, et al., American Government: Texas Edition.

17. Young, “Democratic Party,” https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/...mocratic-party. 18. Dautrich, et al., American Government: Texas Edition.

19. Dautrich, et al., American Government: Texas Edition.

20. Dautrich, et al., American Government: Texas Edition.

21. Dautrich, et al., American Government: Texas Edition.

22. Young, “Democratic Party,” https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/...mocratic-party.

23. Dautrich, et al., American Government: Texas Edition.

24. “Yellow Dog and Blue Dog Democrats,” The Texas Politics Project, https://texaspolitics.utexas.edu/arc...4_01/dogs.html.

25. “Yellow Dog and Blue Dog Democrats,” The Texas Politics Project, https://texaspolitics.utexas.edu/arc...4_01/dogs.html.

26 “Overview and History,” Republican Party of Texas, https://www.texasgop.org/overview-and-history/.

27. Young, “Democratic Party,” https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/...mocratic-party.

28. Dautrich, et al., American Government: Texas Edition.

29. Aman Betheja, “Slideshow: John Tower’s Historic 1961 Senate Campaign,” Texas Tribune, June 6, 2014, https://www.texastribune.org/2014/06...enate-campaig/.

30. “Political Notes: Harmony in Texas,” Time, Jan 28, 1957, http://content.time.com/time/subscri...808962,00.html.

31. “Overview and History,” Republican Party of Texas, https://www.texasgop.org/overview-and-history/.

32. “Yellow Dog and Blue Dog Democrats,” The Texas Politics Project, https://texaspolitics.utexas.edu/arc...4_01/dogs.html.

33. Dautrich, et al., American Government: Texas Edition.

34. Dautrich, et al., American Government: Texas Edition.

35. “Overview and History,” Republican Party of Texas, https://www.texasgop.org/overview-and-history/.

36. Dautrich, et al., American Government: Texas Edition.

37. Dautrich, et al., American Government: Texas Edition.