5.1: The History of Voting in Texas

- Page ID

- 129157

Texas shares with many other states—especially with former Confederate states—a history of systematic disenfranchisement of Blacks and poor Whites. The systematic disenfranchisement was rooted in the Texas Constitutions which provided limited suffrage. The Texas Constitutions of 1836 and 1845 only gave the right to vote to White and Hispanic men, but not to African Americans, Native Americans, or women.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, Union troops occupied the Confederate states, and as a precondition for the removal of the occupying troops, the Union required these states to ratify the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments.

The Thirteenth Amendment (1865) abolished slavery.

The Fourteenth Amendment, Section I (1868) established the citizenship of those who had been enslaved:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.1

This was important because until citizenship was established, those who had been enslaved could not claim any of the rights protected by the U.S. Constitution. By granting citizenship to all people born in the United States, including those formerly enslaved, the Fourteenth Amendment guarantees all citizens “equal protection of the laws.”2

Most of the laws concerning the right to vote developed under the guarantee of equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment, even though the Fifteenth Amendment (1870) provides for the right to vote “regardless of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”3 The Fifteenth Amendment does protect against discrimination based on race, but it does not actually guarantee the right to vote. It is the Fourteenth Amendment that has served as the basis for countless landmark Supreme Court decisions instrumental in the fight for equality and the civil and legal rights of Asian Americans (United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 1898), African Americans (Brown v. Board of Education, 1954), Hispanic Americans (Hernandez v. Texas, 1954), women (Reed v. Reed, 1971), LGBTQIA (Obergefell v. Hodges, 2014), Arab Americans (Arab American Civil Rights League [ACRL] v. Trump, 2017), and other minority groups.

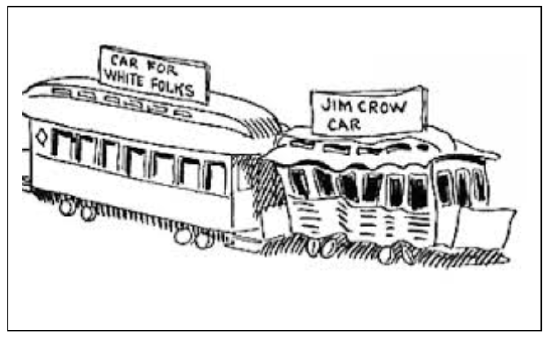

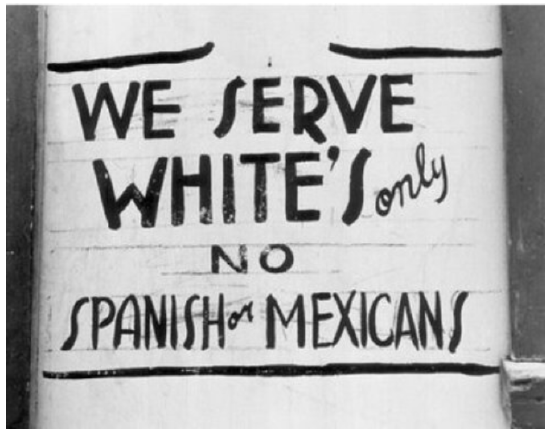

The ratification of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments was not only required for the removal of troops but also for readmission to the Union. Many former Confederate states were angry at having been forced to ratify these Civil War amendments and sought other ways to disenfranchise those who were now free. With the end of Reconstruction in the 1870s, the nation politically abandoned uniform enforcement of the Civil War amendments. Union troops withdrew from the South and, although Blacks were still legally able to vote in 1870, they faced increasing resistance. Like many southern states, Texas legalized segregation through Jim Crow laws (Figure 5.2). These laws, designed to restrict or prevent voter participation by African Americans, replaced the Black Codes of 1866 that kept African Americans in inferior positions politically, economically, and socially. During Jim Crow, Texas utilized several methods for suppressing votes: literacy tests, the secret ballot, poll taxes, and the all-White primary.

Literacy Tests

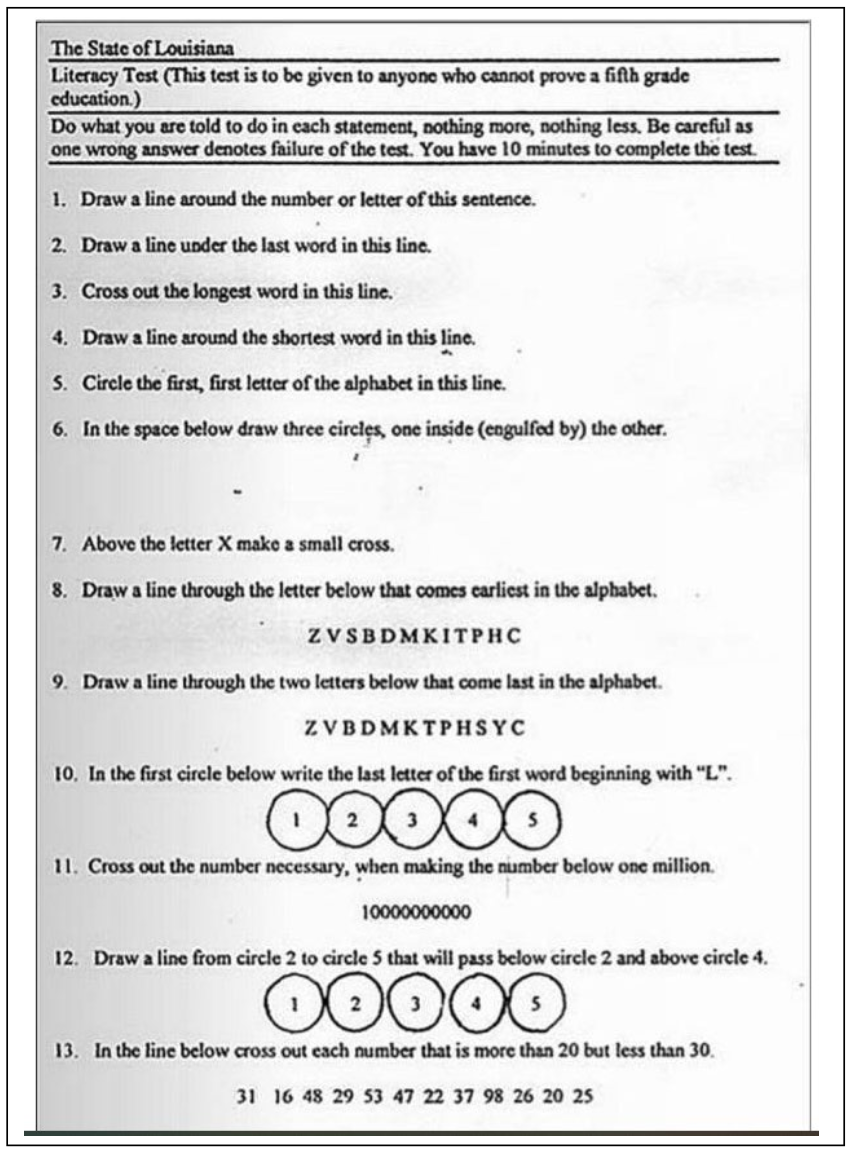

Literacy tests were implemented in southern states as a way to block Blacks from voting (Figure 5.3). People who wanted to vote would have to illustrate that they were able to read and write English. This might not sound like a big deal, but it wasn’t as easy as it sounds. The tests were designed to block African-Americans from voting so some literacy tests required prospective voters to answer a thirty question test in ten minutes and if someone answered incorrectly then that person failed. But what about Whites who couldn’t read or pass the test. Well, there was a special set of rules for them. It was called the grandfather clause. The grandfather clause meant that people who had been able to vote prior to January 1, 1867, or their descendants, would be exempt from requirements like educational, property, or tax requirements for voting. This was a way for White people to circumvent the rules. The grandfather clause was a way to enfranchise White voters who would have been unable to vote based on factors like literacy tests. Although the Fifteenth Amendment made it so southern states couldn’t pass laws saying Blacks cannot vote, they could pass laws that weren’t based on race but would have the effect of helping poor Whites and preventing Blacks from voting. Grandfather clauses stayed in effect until 1915 when the Supreme Court ruled in Guinn v. United States that they violated the Fifteenth Amendment. However, this did not affect the ability of southern states to use literacy tests as long as they did not grandfather anyone in. A point to remember is that these literacy tests were evaluated by White men who then decided if you passed or not. There was nothing that precluded them from simply saying White men passed and Black men did not. See if you can pass the literacy test used in Louisiana as recently as 1964. Would have had to have been grandfathered in?

The Secret Ballot

Until the mid-1880s, elections in the U.S. were public events, full of fanfare, electioneering, and celebration. Everyone knew who voted for whom, and party leaders could see which way the winds were blowing and pull out the stops to change the final result if needed, which could and often did involve corruption. The secret ballot is a voting method where the vote is cast anonymously. The secret ballot, also known as the Australian ballot because it was first passed in Australia before making its way to the U.S, was introduced to protect the secrecy of an individual’s vote and to stop attempts to influence the voter by intimidation, blackmailing, and potential vote buying.

Prior to the implementation of the secret ballot, Texas relied on priming voters. Often the evening before elections the Democratic Party managers would host barbeques where food and alcohol would be served to the Black and Hispanic voters. The alcohol was carefully controlled because the managers wanted to ensure that the voters showed up at the polls the next day. The voters would be given already filled out party ballot in their hands. In South Texas, alien declarant laws were utilized under the Texas Constitution of 1876, which in Article 6 allows any “male person of foreign birth” simply to “declare his intentions to become a citizen” in order vote:

Every male person of foreign birth [not subject to a list of disqualifications] who, at any time before an election, shall have declared his intentions to become a citizen of the United States, in accordance with the Federal naturalization laws, . . . shall also be deemed a qualified elector.4

What this means is that someone could be brought from Mexico to Texas and in order to vote that person just had to declare their intention of becoming a citizen.

According to the study of racial voting rights prepared by historian Susan Cianci Salvatore for the National Historic Landmarks Program, “Prior to the secret ballot, voters went to the polls with printed ballots distributed by political parties with their candidates’ names on them. The secret ballot system prohibited the use of this material and required voters to make their choices from the numerous names and offices printed on official ballots, a task that many of them could not perform.”5 Thus, the end result was that the secret ballot disenfranchised uneducated Americans, in a way that functioned similarly to literacy tests. This new method enabled Texas and many other southern states to legally block the majority of Black voters.

Poll Taxes

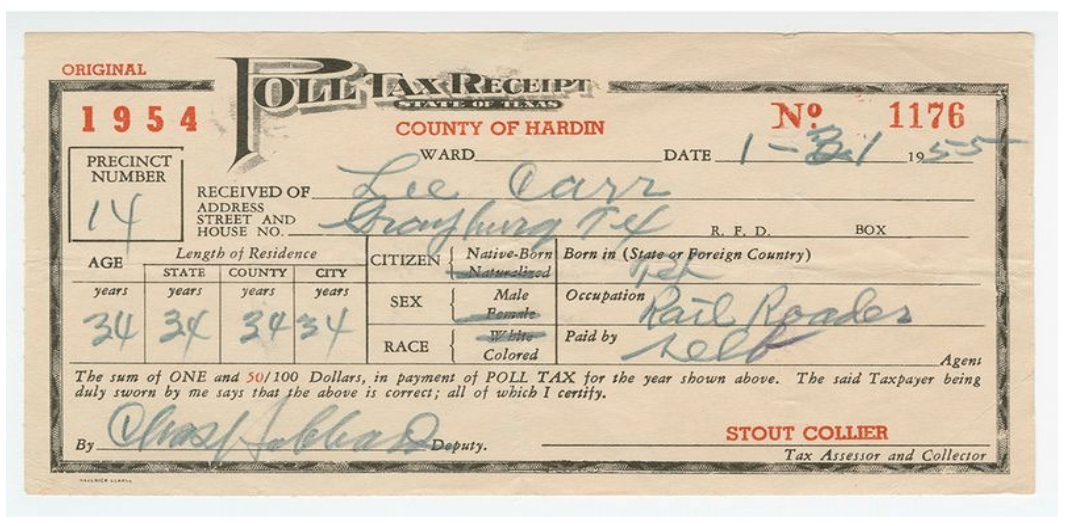

In January 1955 in Hardin County, Texas, Leo Carr had to pay $1.50 to vote. That receipt for Carr's poll tax now resides in the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (Figure 5.4). In today’s dollars, Carr paid roughly thirteen dollars. “It’s a day’s wages,” explains William Pretzer, the museum’s senior history curator. “You’re asking someone to pay a day’s wages in order to be able to vote.”6

Poll taxes added a direct out-of-pocket transaction cost to voting by charging money to vote. Texas adopted a poll tax in 1902. It required that otherwise eligible voters pay between $1.50 and $1.75 to register to vote—a lot of money at the time, and a big barrier to the working classes and poor. Poll taxes, which disproportionately affected African Americans and Mexican Americans, were finally abolished for national elections by the Twenty-Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, adopted in 1964. This prevented states from applying poll taxes for presidential or congressional elections, but states were still able to implement poll taxes in state and local elections, and Texas used the poll tax for two more years after the Twenty-Fourth Amendment was passed. This changed in 1966, with the U.S. Supreme Court decision in United States v. State of Texas that poll taxes in Texas were unconstitutional and unfairly disenfranchised Blacks denying them their basic rights under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The All-White Primary

Texas has a long history of being a one-party state meaning that in Texas, really only one party has a real chance of winning office. That means that the primary elections are where the real election is taking place. Texas was long controlled by the Democratic Party, and the Republican Party, associated as it was with the military occupation of Texas during Reconstruction, did not really stand a chance in Texas elections. Therefore, the Democratic Party primary was truly the deciding factor for who would take office. So, voting in that primary election or preventing people from voting in it was key.

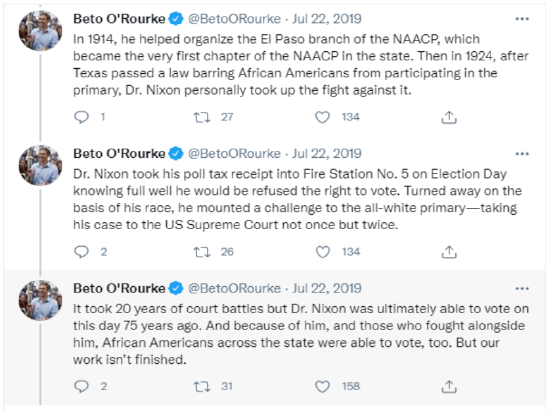

Texas prohibited Blacks from voting in Democratic primary elections. The Supreme Court case Nixon v. Herndon (1927) changed this (Figure 5.5); well, sort of. The Supreme Court ruled this law violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. So, the Democratic Party worked around this ruling. They now continued to block Black votes by having the party’s executive committee prevent Blacks from voting in the Democratic

primaries. The Supreme Court decision in Nixon v. Condon (1932) said this was illegal because the party’s executive committee was formed by the legislature. So, the Texas Democratic Party got more creative. They restricted their membership to only Whites.

The ability to prevent Blacks from voting in the Democratic primary was actually upheld by the Supreme Court in the case Grovey v. Townsend (1935). In that case, a Black Houston resident, R. R. Grovey, sued the country clerk for refusing to give him a ballot in the Democratic primary election. In Texas, the Democratic Party functioned like a private club whose membership was restricted. It was based on this idea of the party as a private club that the Supreme Court based their decision. All-White primaries were not declared unconstitutional until Grovey v. Townsend was overturned in the case Smith v. Allwright (1944) stating that all-White primaries violated the Fifteenth Amendment. Smith v. Allwright was a landmark Supreme Court case because since 1923 the Democratic Party in Texas required all voters in their primary to be White this was because by law the state party was allowed to make its own rules. However, Lonnie E. Smith, a Black citizen of Harris County challenged it by suing the Harris County election official S. S. Allwright for the right to vote in the primary. On April 3, 1944, the Court declared the state law to be unconstitutional. The Court said that by only allowing Whites to participate in the primary election that Smith was being denied equal protection under the law which was in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Hernandez v. Texas

1954 was a big year for landmark Supreme Court cases, the most famous of which was Brown v. Board of Education. With that case, the segregation that was enshrined by Jim Crow laws was overruled, determining that separate schools for Blacks and Whites unconstitutional. But there was a big case that hit close to home that year. It was the year when Texas’s long history of discriminatory practices was challenged. The fight for equal treatment of Hispanics was brought to national forefront with the Supreme Court case Hernandez v. Texas (1954). Prior to this case Mexican Americans faced overt discrimination in Texas. Meaning that Mexican Americans could not go to White schools, eat with Whites, live in the same neighborhoods as Whites, use the same restrooms as Whites, or even be buried in the same cemetery (Figure 5.6). So, does that mean Mexican Americans were classified the same way as African Americans? No, Mexican Americans were actually legally classified as White, but the Hernandez case would show how this legal classification was actually used to discriminate against Mexican Americans.

Pete Hernandez was enjoying a drink in a bar when Joe Espinoza approached him and insulted him. Pete went home and returned with a gun and shot Joe. Pete Hernandez was found guilty of murder by an all Anglo jury in Jackson County, Texas, and sentenced to life in prison. If all Americans are guaranteed a fair trial by a jury of their peers, did he get a fair

trial? In Jackson County where he was tried, no one of Mexican ancestry had served on a jury in the past twenty-five years. If at any time a Mexican American had served on a jury where a White person was on trial it might have been considered fair, but since that had never happened it seemed clear that Pete had not had a fair trial by a jury of his peers. Ironically, in the very Texas courthouse where the judge determined that there was no discrimination in the case of Pete Hernandez, the representing attorneys who were of Mexican heritage themselves could not use the White bathroom. In that very courthouse there was a bathroom for White men and one for colored men that said Hombres aqui (Men Here).

Gustavo “Gus” Garcia, a Mexican American civil rights lawyer, represented Pete in what would be the first Mexican American case in front of the Supreme Court. Gus Garcia was well spoken and brilliantly argued his case, that Mexican Americans were “a separate class, distinct from‘whites’”7 by which Garcia meant that Mexican Americans were indeed a class apart, more than either Black or White, and therefore an all-Anglo (White) jury did not constitute the jury of your peers that is guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution, and the Supreme Court delivered a unanimous decision that Mexican Americans were entitled to protection under the Fourteenth Amendment. Pete Hernandez received a new trial by a jury of his peers where he was convicted of murdering Joe Espinoza. However, the case was not about his guilt or innocence, but instead about getting a fair trial. This case, like Brown v. Board of Education also in 1954, paved the way for change and provided the first step towards equal rights.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was an important piece of legislation during the administration of President Lyndon Baines Johnson. Its aim was to protect minorities but particularly Blacks from the voting barriers that still existed in many southern states, including Texas. States that had a history of discriminatory practices when it came to voting were now required to get preclearance for any electoral changes. Preclearance included a process known as

redistricting. While the number of representative each state sends to the U.S. Congress is determined by the national census, conducted every ten years, in Texas the districts that these congress people represent are drawn by the state legislature. Redistricting is the drawing of geographical boundaries to proportionally distribute representation by population.

When these geographical boundaries are drawn in a biased way to favor one political party over another it is called gerrymandering. Gerrymandering for political party dominance is not illegal as long as it is not done to discriminate by race. Such partisan gerrymandering in favor of Republican districts began in earnest in 2003 when Republicans gained control of both the state legislature as well as the governor’s office. Republicans claimed districts had been gerrymandered in favor of Democrats and now it was their turn. The Democratic representative to the U.S. Congress from Fort Worth, Marc Veasey, puts it this way, Texas has “created a system in which the elected officials are choosing their constituents, not the other way around.”8

In the Supreme Court case Shelby County v. Holder (2013) a key portion of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was struck down. In that case, preclearance of changes in voting laws for those states with a history of voter suppression was invalidated. In his announcement of the Supreme Court’s reason for removing the preclearance condition of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Chief Justice John Roberts explained that it was based on “decades-old data related to decades-old problems, rather than current data related to current needs.”9 He pointed to the fact that now “voting tests were abolished, disparities of voter registration and voter turnout due to race were erased, and African Americans attained political office in record numbers.”10 Chief Justice Roberts goes on to clarify that, “Our decision in no way affects the permanent, nationwide ban on racial discrimination in voting . . . [but rather reflects that] Our country has changed, and while any racial discrimination is too much, Congress must ensure that the legislation it passes to remedy that problem speaks to current conditions.”11 This decision allowed Texas to change its voting laws without approval from the federal government as long as new voting laws do not disenfranchise voters based on race. Since the 2013 ruling, Texas has installed the most restrictive voting requirements of all of the states, including strict voter identification laws, strict vote-by-mail laws, and a reduction in both the number of polling places and drop-off points for vote-by-mail ballots.12

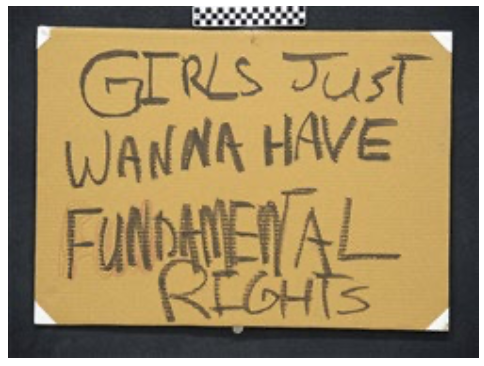

Girls Just Want to Have Fundamental Rights!

Ok, so you’ve read a lot about men and voting but what about women (Figure 5.7)? Well, women got the right to vote with the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment on August 18, 1920. Remember that even after congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment, thirty-six states had to ratify it for it to become law. This was one small step in the fight for women’s equality. For a long time, the popular view was that a women’s place was in the home. Married women could not own property or really anything; it all belonged to her husband. And ladies, if you worked, well, that money wasn’t yours; it belonged to your husband. The fight for women’s suffrage, meaning the right to vote, really gained national prominence in July 1848 when a group of 300 women met in Seneca Falls, New York.

In Texas, amending the Texas Constitution to enfranchise women was considered during the state Constitutional Conventions in 1868-69 and 1875; however, it was rejected by the delegates both times. The fight did not end there. The fight both for and against suffrage amped up in the 1910s. In 1918 the women of Texas won the right to vote but only in primary elections not in the general elections (Figure 5.8). On June 4, 1919, congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment. On June 23, 1919, the Texas legislature met in a special session and on June 28, 1919, Texas ratified the Nineteenth Amendment making it the first southern state to do so. It took until August of 1920 for the amendment to be ratified by thirty-six states making it officially part of the U.S. Constitution.

Hispanic Voices The fight for women’s suffrage was not just fought by non-Hispanic White women; it was a fight that crossed cultural and racial bounds. In 1911 Mexican American journalist, Jovita Idár, championed the cause of Mexican Americans. She wrote articles for her family’s Spanish language newspaper, La Crónica. She called on working women to join the fight for the vote, pointing to recently enfranchised women in California as a model. "Working women . . . proudly raise your chins and face the fight,"13 she implored. "The time of your degradation has passed."14 That same year, and again in 1913, resolutions to amend the Texas Constitution to enfranchise women were introduced in the Texas legislature and were defeated. Black Voices You often hear about the White women that fought for the right to vote, but what about Black women? There were many Black suffragists too. Many of the women who were fighting against racial oppression and slavery as abolitionists were also fighting for civil rights, namely the right to vote. Mary Ann Shadd Cary was one of these heroes. She was born in Wilmington, Delaware, and had twelve siblings! She helped fugitive slaves and was the first Black women to edit a newspaper. She became a teacher and not only taught but established schools for Black children in several states as well as Canada. She was also the first Black female law student at Howard University and earned her law degree there. She went on to fight for all women and their right to vote. As a suffragist, she testified along with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton before the Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives. Fannie Barrier Williams, Charlotte Forten Grimke, Mary Church Terrell, Septima Poinsette Clark, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Nannie Helen Burroughs, and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper were all Black women who fought for equality and were instrumental suffragists in the fight for the Nineteenth Amendment.

However, the Nineteenth Amendment did not really guarantee the right to vote to Black women here in Texas because things like the poll tax, literacy tests, the grandfather clause, and all-White primaries prevented Black women from participating. In addition, the National Women’s Party did not include Black Women as a focus of the suffrage movement. In her book on African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850-1920, Rosalyn Terborg-Penn writes:

When the African American women suffragists sought assistance from the National Woman's Party, the party's leadership position was that, since Black women were discriminated against in the same ways as Black men, their problems were not women's rights issues, but race issues. Therefore, the NWP felt no obligation to defend the right of African American women as voters.15

Nevertheless, women like Lulu White, a native Texan, devoted her life to fighting for the right to vote, equal pay for equal work, and desegregation. White worked tirelessly for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and worked her way to becoming the full-time executive secretary of the Houston branch, a first for a woman in the South. This suffragist fought alongside the NAACP to eliminate the all-White primary. The civil rights attorney at the NAACP, Thurgood Marshall, successfully argued the Houston case against the all-White primary in front of the Supreme Court in the landmark case discussed previously in this chapter, Smith v. Allwright. Thurgood Marshall would go on to become the first African American appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

- U.S. Const. amend XIV, § 1, https://constitutioncenter.org/inter.../amendment-xiv.

- U.S. Const. amend. XIV, § 1, https://constitutioncenter.org/inter.../amendment-xiv.

- U.S. Const. amend. XV, § 1, https://constitutioncenter.org/inter...t/amendment-xv.

- Tex. Const. art. VI, § 2, https://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/const...cle-6-suffrage.

- Susan Cianci Salvatore, “Civil Rights in America: Racial Voting Rights,” National Parks Service, revised 2009, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/telling...tingRights.pdf.

- William Pretzer, quoted in Allison Keyes, “Recalling an Era When the Color of Your Skin Meant You Paid to Vote,” Smithsonian Magazine, Mar. 18, 2016, “https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smith...ote-180958469/.

- Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954), pp. 470-480.

- Eric Griffey, “A Brief History of Texas Gerrymandering,” Spectrum News 1, Oct. 14. 2020, https://spectrumlocalnews.com/tx/san...errymandering-.

- Shelby County v. Holder, 570 U.S. 529 (2013), Opinion of the Court, p. 20, https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinion...12-96_6k47.pdf.

- Shelby County v. Holder, 570 U.S. 529 (2013), Opinion of the Court, p. 20, https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinion...12-96_6k47.pdf.

- Shelby County v. Holder, 570 U.S. 529 (2013), Opinion of the Court, p. 24, https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinion...12-96_6k47.pdf.

- “ How Hard Is It to Vote in Your State?” NIU Newsroom, Northern Illinois University, Oct.13, 2020, https://newsroom.niu.edu/2020/10/13/...in-your-state/; “Voting Laws Roundup: March 2021,” Apr. 1, 2021, Brennan Center, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-wo...roundup-march- 2021.

- Jovita Idár, quoted in “Texas and the Nineteenth Amendment,” National Parks Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/texas-w...-s-history.htm.

- Idár, quoted in “Texas and the Nineteenth Amendment,” https://www.nps.gov/articles/texas-w...-s-history.htm.

- Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850-1920 (Bloomington, IN: University of Indiana Press, 1998), quoted in Jen Rice, “How Texas Prevented Black Women From Voting Decades After the 19th Amendment,” KHUT TV 8, June 28, 2019, https://www.houstonpublicmedia.org/a...right-to-vote/.