7.5: How a Bill Becomes a Law in Texas

- Page ID

- 129169

Once the House and Senate convene at the beginning of each session, and the House elects a speaker, each chamber must adopt rules that will govern its operations. The House and Senate operate differently and have very different rules of procedure—each adopted as a simple resolution by a majority in each chamber. The Texas Constitution provides some rules for both the House and Senate, but most procedural matters are left for the members to decide. Once House and Senate rules are adopted, they are rarely changed, although most rules can be suspended on a case-by-case basis with a supermajority vote.

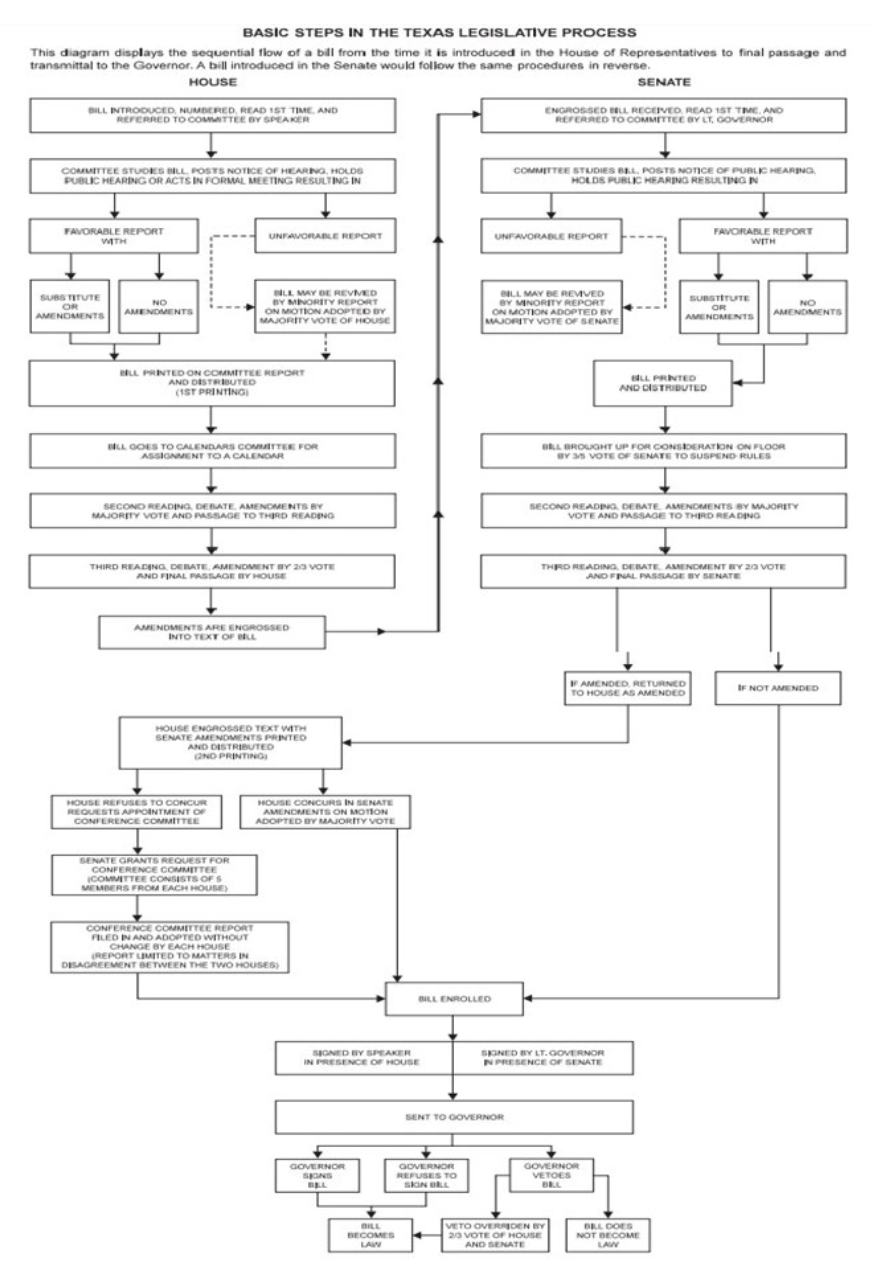

Only after rules are adopted can the legislature begin considering bills. The steps in the process include (1) introduction; (2) committee action; (3) floor action; (4) conference committee (if necessary) (these steps are repeated in the Senate); and (5) governor’s action

Introducing a Bill

A representative or senator often gets an idea for a bill by listening to the people he or she represents and then working to solve their problem. Some bills are suggested by interest groups, often with ties to the legislator’s district. A bill may also grow out of the recommendations of an interim committee study conducted when the legislature is not in session. The idea is researched to determine what state law needs to be changed or created to best solve that problem. A bill is then written by the legislator, often with legal assistance from the Texas Legislative Council, a legislative agency which provides bill drafting services, research assistance, computer support, and other services for legislators.

Once a bill has been written, it is introduced by a member of the House or Senate in the member’s own chamber. Sometimes, similar bills about a particular issue are introduced in both houses at the same time by a representative and senator working together.

After a bill has been introduced, a short description of the bill, called a caption, is read aloud while the chamber is in session so that all of the members are aware of the bill and its subject. This is called the first reading, and it is the point in the process where the presiding officer assigns the bill to a committee. This assignment is announced on the chamber floor during the first reading of the bill.

The Committee Process

Most of the real work of the Texas legislature is done at the committee level. The floor of the 150 member House of Representatives (or even the thirty-one member Senate) is not a useful forum for a detailed line-by-line study of potential legislation. Accordingly, the House and Senate are divided into committees of various types.

A standing committee is a permanent committee with jurisdiction over legislation dealing with specific subjects. The House Corrections Committee, for example, has exclusive jurisdiction over bills dealing with the state’s prison system.

Temporary committees include joint committees, conference committees, and interim committees. A joint committee (usually temporary) includes members of both the House and Senate, and generally examine policy issues rather than individual bills. The 2019 session saw the appointment of a joint advisory committee to oversee the Texas Infrastructure Resiliency Fund, a source of funding to improve critical infrastructure following the unprecedented destruction caused by Hurricane Harvey in 2017. A conference committee, consisting of five senators and five representatives, resolves the differences between a House and Senate-passed version of one specific bill. An interim committee studies a specific policy issue between regular legislative sessions.

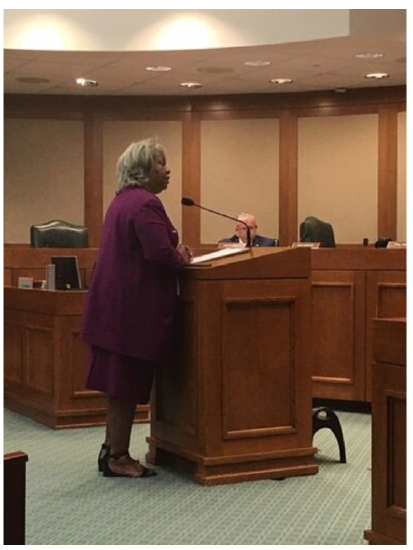

The chair of each committee decides when the committee will meet and which bills will be considered. The House rules permit a House committee or subcommittee to meet: (1) in a public hearing where testimony is heard and where official action may be taken on bills, resolutions, or other matters; (2) in a formal meeting where the members may discuss and take official action without hearing public testimony; or (3) in a work session for discussion of matters before the committee without taking formal action (Figure 7.6). In the Senate, testimony may be considered and official action may be taken at any meeting of a Senate committee or subcommittee.

If you have ever watched a congressional hearing on CSPAN, you may have noticed that testimony is by invitation only, with witnesses chosen carefully by the majority party to support its chosen narrative. Texas House and Senate Committees allow anyone to testify on any bill, with hearings occasionally lasting all night to make sure everyone has a chance to speak.

A House committee or subcommittee holding a public hearing during a legislative session must post notice of the hearing at least five calendar days before the hearing during a regular session and at least twenty-four hours in advance during a special session (Figure 7.7). For a formal meeting or a work session, written notice must be posted and sent to each member of the committee two hours in advance of the meeting or an announcement must be filed with the journal clerk and read while the House is in session. A Senate committee or subcommittee must post notice of a meeting at least twenty-four hours before the meeting.

After considering a bill, a committee may choose to take no action or may issue a report on the bill. Many bills die in committee, sometimes referred to as pigeonholing. An unofficial but important job of the committee chair is to help members avoid the embarrassment of a public vote to kill their bill, and to protect members from having to cast that vote. When the chair sees that the committee members don’t like a bill, it is generally just left pending or referred to a subcommittee that will never meet. If the committee wants to advance a bill to the floor, the committee report, expressing the committee’s recommendations regarding action on a bill,

includes a record of the committee’s vote on the report, the text of the bill as reported by the committee, a detailed bill analysis, and a fiscal note or other impact statement, as necessary. The report is then printed, and a copy is distributed to every member of the House or Senate.

In the House, a copy of the committee report is sent to either the Committee on Calendars or the Committee on Local and Consent Calendars for placement on a calendar for consideration by the full House. In the Senate, local and noncontroversial bills are scheduled for Senate consideration by the Senate Administration Committee. All other bills in the Senate are placed on the regular order of business for consideration by the full Senate in the order in which the bills were reported from senate committee. A bill on the regular order of business may not be brought up for floor consideration unless the Senate sponsor of the bill has filed a written notice of intent to suspend the regular order of business for consideration of the bill.

Floor Debate

When a bill comes up for consideration by the full House or Senate, it receives its second reading. The bill is read, again by caption only, and then debated by the full membership of the chamber (Figure 7.8). Any member may offer an amendment, but it must be approved by a majority of the members present and voting to be adopted. The members then vote on whether to pass the bill. The bill is then considered by the full body again on third reading and final passage. A bill may be amended again on third reading, but amendments at this stage require a two-thirds majority for adoption. Although the Texas Constitution requires a bill to be read on three separate days in each house before it can have the force of law, this constitutional rule may be suspended by a four-fifths vote of the House in which the bill is pending. The Senate routinely suspends this constitutional provision in order to give a bill an immediate third reading after its second reading consideration. The House, however, rarely suspends this provision, and third reading of a bill in the House normally occurs on the day following its second reading consideration.

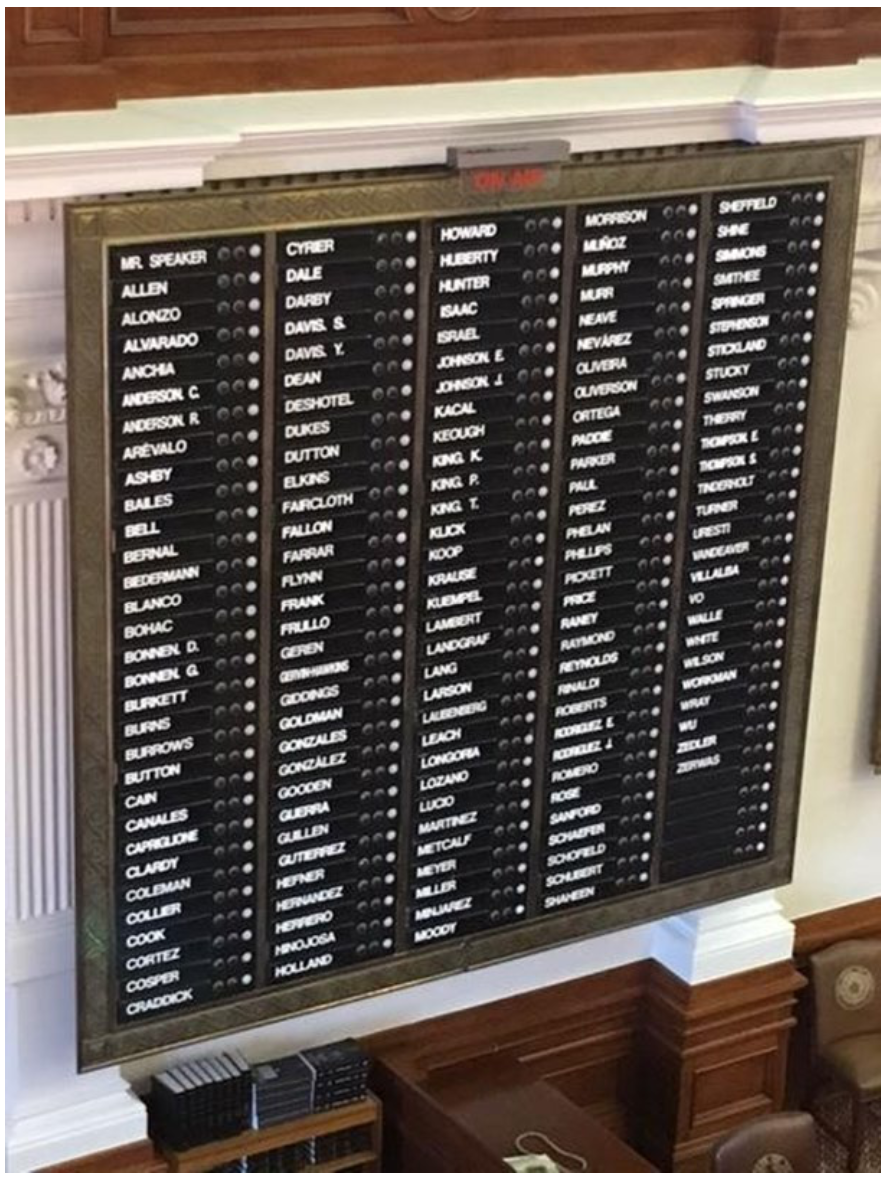

In either house, a bill may be passed on a voice vote or a record vote. In the House, record votes are tallied by an electronic vote board (Figure 7.9) controlled by buttons on each member’s desk (Figure 7.10). In the Senate, record votes are taken by calling the roll of the members.

If a bill receives a majority vote on third reading, it is considered passed by that chamber. When a bill is passed in the House where it originated, a new copy of the bill which incorporates all corrections and amendments is prepared and sent to the other chamber for consideration. In the second chamber, the bill follows basically the same steps it followed in its chamber of origin. When the bill is passed in the other chamber, it is returned to the originating chamber with any amendments that have been adopted simply attached to the bill.

Debate in the 150-member House of Representatives is more carefully controlled than in the Senate. The author of the bill being debated stands at the “front mic,” in front of the Speaker’s podium, to explain the bill and answer questions. Representatives wishing to question (or argue with) the author speak from the “back mic” near the center of the House Chamber.

Speakers from either mic are generally limited to three minutes. Texas senators each have their own microphone at their desk and, once recognized to speak, may continue for as long as they wish. Toward the end of a session, this can occasionally take the form of a filibuster, in which a senator purposely continues speaking for an extended period of time in order to delay action and force a compromise. Unlike a U.S. Senate filibuster, which is strictly a procedural exercise, a filibuster in the Texas Senate is an endurance sport. The filibustering senator must remain standing at his or her desk, speaking on the issue before the Senate. He may yield to answer questions—a crafty senator will arrange in advance for a team of allies on his issue to take shifts asking very long questions in what is known as a tag team filibuster. Several state legislatures allow filibusters, but former Texas Senator Bill Meier, a Democrat from Euless, holds the world’s record for a forty-three hour filibuster in 1977. Democratic State Senator Wendy Davis famously spoke for thirteen hours in 2013 against a bill that would require women to get sonograms in order to have an abortion, a bill widely considered to effectively limit a woman’s access to abortion. The session ended before a vote could be taken, thus killing the bill, though the bill was passed several days later in a subsequent special session.

Conference Committees and Action on the Other Chamber’s Amendments

If a bill is returned to the originating chamber with amendments, the originating chamber can either agree to the amendments or request a conference committee to work out differences between the House version and the Senate version. If the amendments are agreed to, the bill is put in final form, signed by the presiding officers, and sent to the governor.

Conference committees are composed of five members from each chamber appointed by the presiding officers. Once the conference committee reaches agreement, a conference

committee report is prepared and must be approved by at least three of the five conferees from each chamber. Conference committee reports are voted on in each house and must be approved or rejected without amendment. If approved by both houses, the bill is signed by the presiding officers and sent to the governor.

In recent decades, the legislature has adopted end-of-session rules to prevent the flood of hastily-conceived legislation commonly seen near the end of each legislative session for much of the state’s history. After the 119th day of the 140-day session, House committees can no longer report House bills and joint resolutions. House bills cannot be brought up for initial floor debate after the 122nd day. These restrictions continue to build until, by the last several days, the legislature is restricted mostly to approving or rejecting conference committee reports and passing honorary resolutions.

Governor’s Action

Upon receiving a bill, the governor has ten days in which to sign the bill or reject it with a veto, Otherwise, the bill become law without a signature. If the governor vetoes the bill and the legislature is still in session, the bill is returned to the house in which it originated with an explanation of the governor’s objections. A two-thirds majority in each house is required to override the veto. If the governor neither vetoes nor signs the bill within ten days, the bill becomes a law. If a bill is sent to the governor within ten days of final adjournment, the governor has until twenty days after final adjournment to sign the bill, veto it, or allow it to become law without a signature. Since most bills do not reach the governor until the end of the regular session, this has the practical effect of making a Texas governor’s veto unilateral. The last Texas governor to have a veto overridden was William Clements, whose early veto of a bill on hunting and fishing regulations in Comal County was overridden in 1979—and that was the first Texas veto override since 1941.

The Texas Constitution also allows the governor the power of line-item veto. This power, which the president of the United States can only envy, allows the governor to veto specific spending item from an appropriations bill without vetoing the entire bill. Some governors have used this power aggressively to remove spending items they considered wasteful or unnecessary. Following the 2019 session, Governor Abbott signed the state budget into law with no line-item vetoes, the first governor since 1955 to sign a budget into law without a single change.

Enactment (When Laws Go Into Effect)

Bills passed by the legislature rarely take effect immediately. Most bills are written to become effective on September 1, which matches the beginning of the state’s fiscal year (The state budget covers a period from September 1 after the legislature adjourns through August 31 two years later). The state constitution mandates that bills cannot take effect sooner than ninety days after passage unless two-thirds of each house vote to put the bill into immediate effect. Sometimes, bills are written with an intentionally longer fuse. Texas’ “one sticker” law, passed in 2013, which eliminated the state’s longstanding requirement that cars have separate registration and inspection stickers, was phased into effect over two years so that existing stickers already paid for by Texans would remain valid.