13.4: Revenue, Funds, and Expenditures

- Page ID

- 129218

A budget regulates a state’s cash flow. There are three aspect to this flow. The first is the definition of which sources of revenue will be used to gather money into the treasury. The second is determining which of the many funds the revenue will be allocated to. The third is the expenditure itself. While this process is the same for all areas of funding in the state, the specifics vary. Here is a quick example of how these work in action. When you pump gas into your car—assuming you do, of course—you are charged a twenty cents per gallon gasoline tax.15 This tax is sent by the owner of the gas station to the comptroller’s office who then places it in the State Highway Fund. The Texas Department of Transportation can then draw from the State Highway Fund for “the furtherance of public road construction and for establishing a system of state highways.”16 This is a simple way to describe the process. Each stage is more complex than this, but this describes the general structure that efficiently ties the source of revenue to the good used by that source. Much of the information drawn for the discussion of revenue, funds, and expenditures are from the Fiscal Size-Up, discussed earlier in the chapter, which is written after the end of each legislative session by the staff of the Legislative Budget Board to describe as fully as possible the contents of the General Appropriations Bill.

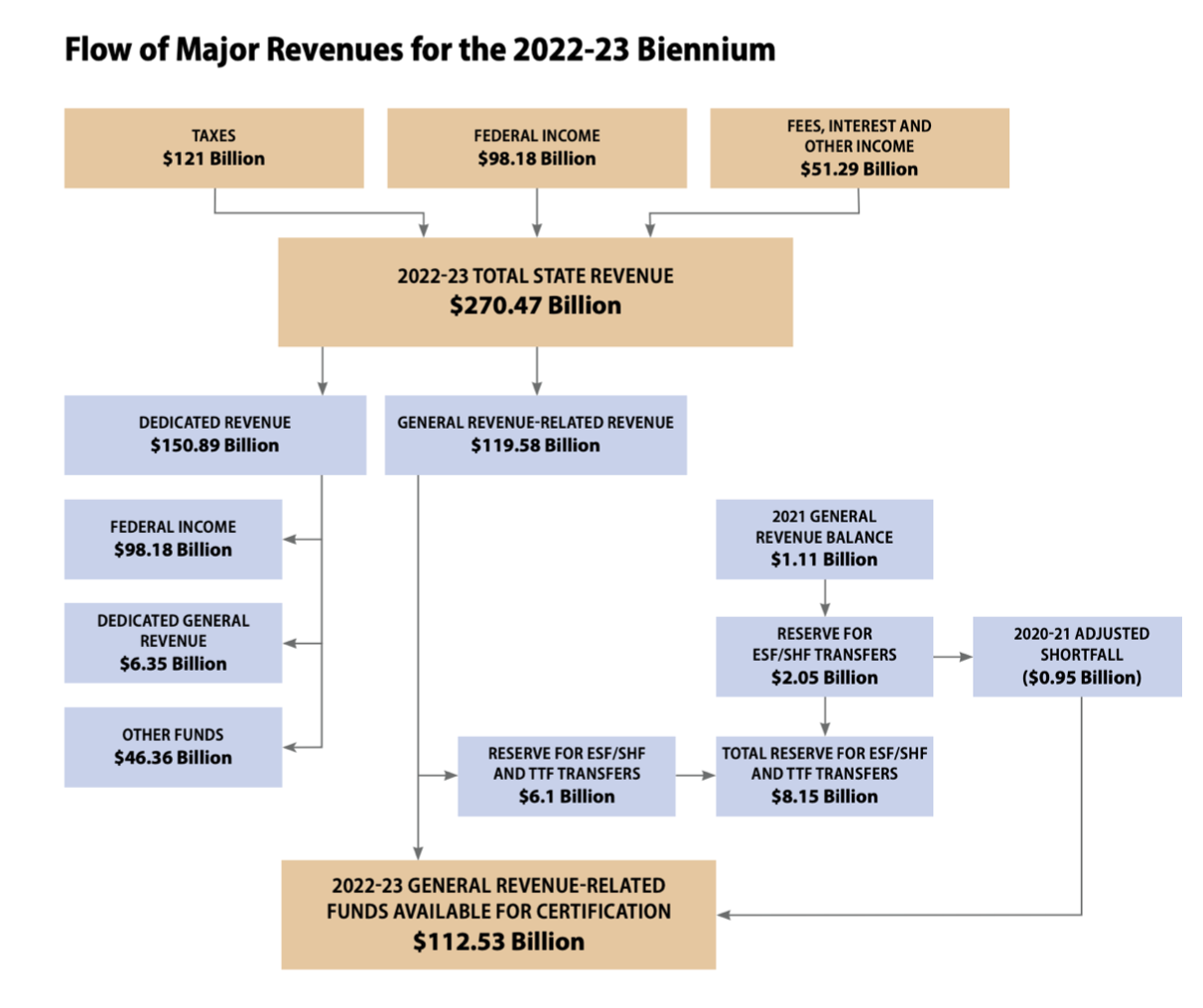

There are various sources of revenue for the state (Figure 13.8). Not all revenues come from taxes. Some come from investments, fees, and penalties. Even more comes from the national government in the form of grants.

These revenues are tied into a large number of funds, separate accounts in the state treasury that designate how the revenue will be spent. Some of these are flexible, meaning the money can be shifted as deemed necessary. Others are designated to specific purposes, meaning that the revenue collected is to be spent in a particular manner, which brings us to expenditures. There are approximately 200 funds are in the Texas Treasury.

Many of the funds in the Texas Treasury are fixed funds, which means that the amount of money they contain is tied into a specific source. The amount of money they contain depends on the activity from that source. In turn, the amount of money that can be spent is fixed as well. As a consequence, much of the budget is set and not subject to revision by the legislature. The only part of the budget that is truly flexible is contained in the General Revenue Fund. Items in the fund can be shifted as the legislature, and the executive, see fit.

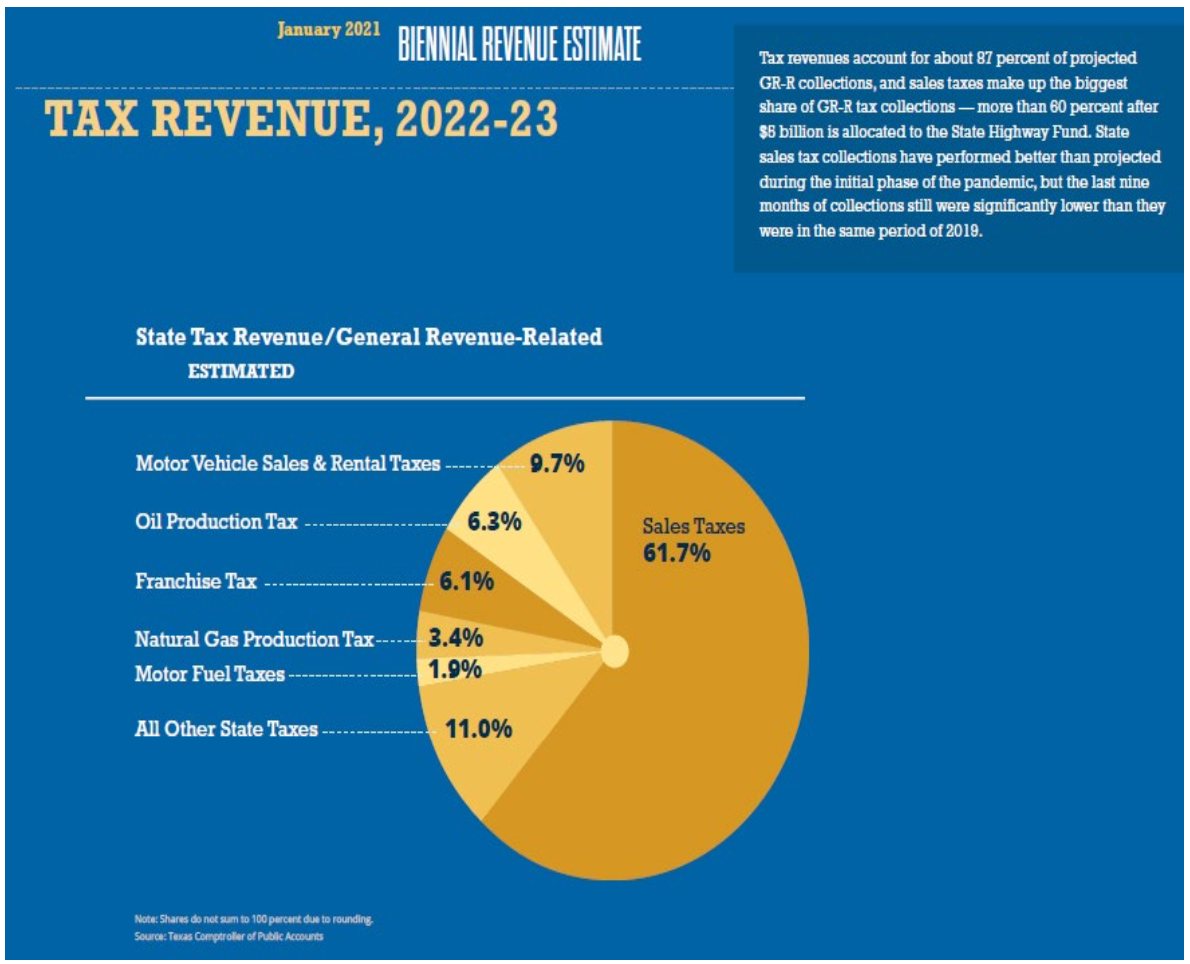

Tax Revenue

Figure 13.9 breaks down where tax revenue is expected to come from in the 2022-2023 budget. Tax revenue is expected to be down some from the 2020-2021 budget, which expected revenue collected from tax breaks to total $123.9: Sales Tax ($72.5 billion); Motor Vehicle Sales and Rental taxes ($10,192.76 billion); Franchise tax ( $8,836.80 billion); Oil Production taxes- ($7,837.50); Motor Fuel Taxes ($7,670.56 billion); Insurance taxes ($5,485.38 billion); Natural Gas Production tax ($3,067.14); Alcoholic Beverage taxes ($2,911.00 billion); Cigarette and Tobacco taxes ($2,523.99 billion); Hotel Occupancy tax ($1,352.42 billion); Utility taxes ($959.30 million); Other taxes ($647.74 million).

Sales Tax The sales tax is the largest tax collected by the state government (see Figure 13.9). A sales tax can be collected by any local governments as well. The state has placed a limit of 6.25 percent on the state rate, and a total of 8.25 percent on the overall rate including what is imposed locally. For example, a resident in Houston pays a total of 8.25 percent sales tax. In addition to the 6.25 percent imposed by the state, one percent is collected by the City of Houston and one percent by the Houston Metropolitan Transit Authority. The state has exempted certain items from the sales tax, such as property used in manufacturing, food purchased for home consumption, gas and electricity, and water. For items that are not exempt, the tax is added to the costs of the purchased item by the seller who is then responsible for collecting the moneys and sending the proper amount to the state.

Motor Vehicle Sales and Rentals Tax People who purchase and rent one of a large variety of motor vehicles must pay a tax that is to be collected by the business owner. This includes automobiles, trucks, trailers, and motorcycles. For rentals of less than thirty days, the tax is ten percent. Longer rentals are taxed at 6.25 percent as is the standard sales tax rate. The vehicle sales tax is also 6.25 percent though a complicated system of exceptions can reduce it. Franchise Tax Despite the official name, this is a tax on business. It is also called a margins tax because of changes made in 2008 in how the tax was calculated. A variety of methods of calculation were created which limited how much of a business entity was subject to taxation. One method is to only make seventy percent of the total revenue of a business taxable. This seventy percent is the margin, which explains the use of the term. The bulk of the franchise tax is allocated to the General Revenue Fund while the remainder is allocated to the Property Tax Relief Fund.

Oil and Natural Gas Production Tax These taxes are, respectively 4.6 percent and 7.5 percent of the market value of the amount of each product drawn during the biennium. This is a severance tax since it is a one-time tax when oil or gas is removed from beneath the ground. Its market value is based on the average price of each item during each fiscal year on the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX). These are important since they are major contributors to the Economic Stabilization Fund, which will be discussed later in the chapter.

Motor Fuel Taxes These are taxes upon the three types of motor fuel. Motor fuel taxes were the source of the example used above regarding the flow of money in the state budget. Gasoline and diesel are taxed at twenty cent per gallon, and liquefied and compressed natural gas are taxed at fifteen cents per gallon. Seventy-five percent of these revenues are placed in the State Highway Fund, and twenty-five percent are allocated to public education.

Motor fuels taxes, along with many listed below, are excise taxes. These are taxes imposed on the merchants who sell the product and are usually applied on a per-unit basis, for example, a gallon. Merchants often raise the prices of their goods as a way of passing them onto the consumers. Since they are not itemized, these are often called hidden taxes. Consumers are not necessarily aware that they are paying them, as opposed to the sales tax which is listed on receipts.17

Sin Taxes Certain taxes are called sin taxes because their purpose is not only to collect revenue but to increase the costs of the behavior in question. Drinking and using tobacco products impose costs on the greater society in terms of public health and public safety. This increases the costs associated with hospitals and law enforcement. Ideally, the increased costs imposed on the products reduces the tendency of people to engage in that activity. This should, in turn, reduce social costs. But in case it does not, the increased revenue can be allocated towards addressing the problems created by that behavior.

The state imposes a tax of $70.50 per 1000 cigarettes weighing three pounds or less, and $72.50 per 1000 cigarettes weighing three pounds or more. A portion of the revenue is deposited in the Physician Education Loan Repayment Program, and the remainder is deposited in the Property Tax Relief Fund.

Texas collects revenue from a variety of alcoholic products. As with motor fuel taxes, these are called volume-based excise taxes (that is, the taxes are fixed amounts per a set unit of volume). They are imposed on merchants. Wine and beers vendors are each responsible for paying an excise tax of twenty cents per gallon. Vendors of distilled liquors must pay an excise tax of $2.40 per gallon. Controversially, sales of all three are also subject to the 6.25 percent general sales tax, which is paid by the consumer.18 Critics of tax policy often point out that separate taxes are often collected at various points in the market.

Regressive and Progressive Taxes One of the more frequent criticisms made of the sales tax, and all other taxes related to the purchase of items, is that it is a regressive tax, meaning that it imposes a higher burden on the poor than on the middle class, and a higher cost on the middle class than the wealthy. This is because the poorer you are, the greater a percentage of your income is spent on basic needs, which are often subject to the sales tax. A greater percentage of the income of the poor is therefore taxed, which makes it regressive. This is different from how the income tax is treated at the national level where the rate of taxes increases with each incremental increase of income. Since incomes at a high level—say $400,000—are taxed at a higher rate, the wealthy pay more in taxes as a percentage than the poor, so this is called a progressive tax.

A Word about State Property and Income Taxes Two types of taxes that the state cannot collect are:

- State Property Taxes;

- State Income Taxes.

At one point the state of Texas, and not only local governments, could collect a property tax. It funded a significant percentage of state expenditures. But in 1968, the state put an end to it. There was a simple reason in doing so, it was very difficult to manage statewide. A key requirement of taxes is that they be able to be collected. This was not the case for the state property tax. Collections were erratic, property undervalued, tax assessor-collectors sometimes corrupt, and following the Great Depression many properties were delinquent. Trying to collect them simply became more trouble than they were worth, and Texas began to rely more on the sales tax, among others, for revenue. The sales tax was, at root, much easier and cheaper, to collect.19

Non-Tax Revenue

The chart in Figure 13.8 identifies non-tax income generally as federal receipts and fees, interest, and other income. In addition to fees and interest, the Texas Lottery and Land Income are other sources of non-tax revenue for the state. More recently, bonds have become a way for Texas to generate revenue.

Federal Receipts The largest single source of revenue for the state—33.8 percent of all revenue—are federal receipts. These are expected to total $87.8 billion in 2020-2021. The state receives federal revenue in the form of matching grants and then uses to implement federal policies, especially those that impact individuals. Chapter 2 on federalism discusses cooperative federalism, a term used to describe when the national government became involved in areas of public policy previously reserved to the states.

Some of these policies can be traced to the New Deal in the 1930s, others to the Great Society in the 1960s. Some policies are run by the national government and provide direct benefits to people. The two most prominent are those for individuals over sixty-five: Social Security and Medicare. Others are run by the states, which are allowed to place restrictions on them. These include funds for the poor, such as Medicaid, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

Social Security and Medicare are federal programs that benefit those over sixty-five. The former provides funds for retirement, the later provides medical assistance. Each is funded by payroll taxes drawn from a person’s paycheck, and matched by that person’s employer. As a result, the funds eventually received are a reimbursement of the money paid into the accounts. The states have no consequential role in either policy. This is, at least in part, a result of the programs being relatively uncontroversial. This is not to say that controversies do not exist with either program, but the general sense is that the people who receive these benefits, earned them and are therefore entitled to them. After all, they paid into funds—with matching grants by their employers. That make them deserving of the benefits.

This is not the case with Medicaid, TANF, or SNAP. These programs are made available to the poor, and are paid by incomes taxes, meaning that recipients have likely not contributed to their own welfare. Political battles often exist over whether those who receive Medicaid, TANF, or SNAP, are worthy of the benefits. Even if they are, the general sense in states like Texas is that benefits should be low and only available for a brief period of time.

Licenses, Fees, Fines, and Penalties Licenses, fees, fines, and penalties will likely bring in $13.24 billion in 2020-2021. As you can imagine, this includes a wide variety of items, such as hunting and fishing licenses, vehicle registration fees, penalties related to driving without a license, and past due taxes. The revenue from licenses, fees, fines, and penalties are often allocated to funds related to those receipts. For example, hunting and fishing licenses funds the Texas Wildlife Department and vehicle registration fees are allocated to the State Highway Fund.

Interest and Investment Income Interest and investment income is expected to bring in $4.4 billion in 2020-2021.20

The Lottery The Texas lottery is estimated to bring in $4.6 billion in 2020-2021. While the original 1876 constitution prevented the legislature from allowing for lotteries, amendments beginning in 1980 were ratified authorizing them in certain instances.21 It was promoted as a way to supplement education funding since a portion of its proceeds is transferred to the Foundation School Fund. In 2019, this amounted to $1.5 billion. Since it is a lottery, and it promises payouts, it falls to reason that the dominant cost is payouts to winners. This came to $4.1 billion in 2019. In case you are curious, $70.9 million in winnings was unclaimed.

Land Income Land income is estimated to bring in $4.6 billion in 2020-2021. Land income is derived from mineral royalties and leases, land sales, and the sale of timber and sand. Up until the twentieth century, Texas was capital poor. The availability of land grants lured American immigrants to Spanish and Mexican Texas. After independence, land was made available to Anglo men with the understanding that they would clear and develop it. This would continue after statehood since Texas was able to retain possession of its land. Land grants were also made available to the veterans of the various wars it had been engaged in. This is a practice continued today.

Land grants were significant in funding the internal improvements necessary to promote commerce in the state. The construction of railroads and highways, and the clearing of rivers and development of harbors, among other things, were funded by the granting of land. This included the rights to any minerals—or oil and gas—that might be discovered beneath the surface.

Bonds Since the sale of bonds have become increasingly common as ways to supplement spending in the state, it is necessary to say a word about them. While the state of Texas officially

does not allow itself to go into debt, allowances have been made in recent decades to do so. The primary way of doing so is the sale of bonds. This allows for obtaining revenue for projects that exists outside of the normal revenue collection process.

A bond is similar to an IOU. It is a financial instrument offered in the marketplace to potential buyers. By purchasing the bond for a fixed price, the buyer is promised a specific return—an interest rate—at a particular moment in time. The buyer has to have a reasonable expectation that they will receive their investment back, with the promised interest, at the promised date. In addition to their use at the state level, they are the principle financial instrument local governments use to finance construction projects.

Voters have approved the sale of a number of bonds over the past few decades, as well as the creation of a variety of funds. This allows the state to go into debt, despite the language in the original constitution. It does however require the bonds to be added to the Texas Constitution in a process that involved two-thirds votes by each chamber of the legislature, and a simple majority vote by the electorate.

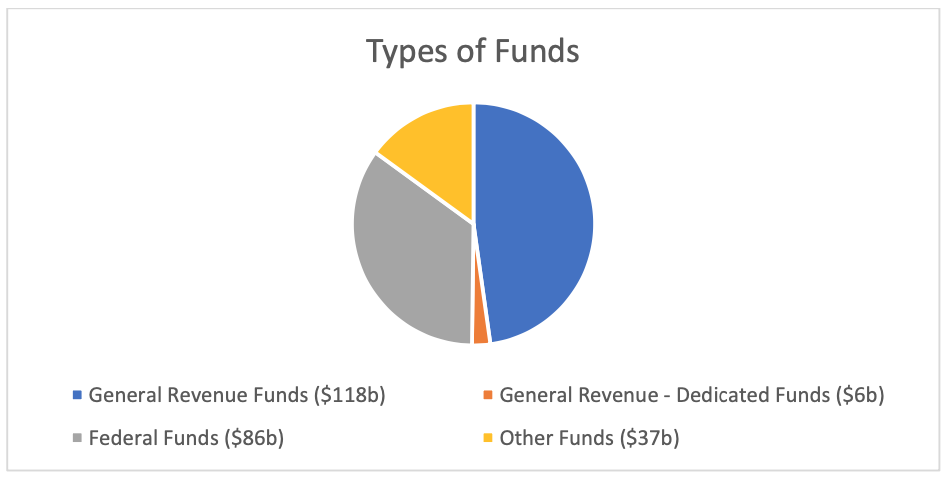

Types of Funds

The revenue that is collected by the state is then deposited in the Texas Treasury. This revenue is not treated the same, however. It goes into one of a variety of funds, some of which were mentioned earlier in the chapter. Some funds are generally available to any area of expenditure, while others are limited in terms of what they can fund. The Texas Treasury contains more than 400 funds, which then determine how they are spent, but these fall into four general categories: General Revenue Fund; Dedicated General Funds; Federal Funds; Other Funds (Figure 13.11).

General Revenue Fund The General Revenue Fund is the state’s primary operating fund. “Expenditures may be made directly from nondedicated General Revenue Funds, or, in some cases, revenue may be transferred from non-dedicated General Revenue Funds to special funds or accounts.”22 Among the taxes deposited initially to the nondedicated General Revenue Fund are the state sales tax, the franchise tax, motor vehicle sales taxes, alcohol and tobacco taxes, the oil production tax, the natural gas tax, and motor fuel taxes. General Revenue Funds also include the Available School Fund (ASF), the Instructional Materials Allotment (IMA), and the Foundation School Program (FSP), which is the primary source of school funding in the state. Dedicated General Funds These are funds included in the General Revenue Fund, but are not transferable. By law they are to be spent on a specific items. These include “more than 200 accounts within the General Revenue Fund that state law dedicates for specific purposes.”23 Federal Funds Federal funds are where the federal receipts mentioned earlier are deposited. Federal funds are grants, allocations, payments, or reimbursements received from the federal government by state agencies and institutions. The largest portion of federal funding appropriations are for the Medicaid program discussed earlier. Other examples of Federal Fund appropriations include grants to Local Educational Agencies, the National School Lunch Program, Transportation Grants and National Highway System Funding, Special Education, Basic State Grants, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

Other Funds In 1991 the legislature placed over 200 funds within the General Fund but created distinct accounts for them which dedicated them to specific uses. Not all funds were included in the consolidation. These make up the bulk of what is found in this broad category. These include some of the more significant funds in the state, including the State Highway Fund, the Texas Mobility Fund, the Property Tax Relief Fund. In addition, this category includes the trust fund, bond proceeds, and interagency contracts.

Economic Stabilization Fund The Economic Stabilization Fund—otherwise known as the Rainy Day Fund24—was established in 1988 to provide an auxiliary source of money should the state’s anticipated revenue fall short, and the state risks running a deficit.25 The impetus behind its creation was the oil crash of the 1980s, which helps explain the connection mentioned earlier in the chapter between oil and gas taxes and the fund.

Expenditures

The legislature is responsible for establishing how revenue is collected, which includes establishing and setting tax rates, but there are constitutional limits on spending established in the Texas Constitution. The Fiscal Size-Up puts these limits into four categories: pay-as-you-go; limits on welfare spending; limits on the rate of growth of appropriations; and limits on debt service.

Pay-as-You-Go As discussed earlier in the chapter, Texas is a pay-as-you-go, balanced budget state, following the mandate of Article 3, Section 49a (The Legislative Branch) of the constitution, which was most recently amended in 1991. As mentioned earlier, the term pay-as- you-go simply means that the state’s budget must balance. Expenditures cannot exceed revenues. Consequently, the state cannot go into debt. As written in 1876, the restriction was severe, which worked well for an agrarian economy. The state’s ability to create debt was limited to casual deficiencies of revenue less than $200,000, repelling invasions, and suppressing insurrection. Debt can also be created if authorized in the constitution itself—a significant exception.

This proved too restrictive for the government of a state transforming into a commercial economy, and the development of the infrastructure necessary to sustain it. Changes in 1991 made the process of acquiring debt easier, but it still required a constitutional amendment which involves a supermajority votes in both houses of the legislature—two-thirds in the House and in the Senate—and a simple majority of the voters in the state. Voters are given the opportunity to approve, or disapprove the sale of bonds to be sold by the state for designated purposes. If the voters of the state approve these bonds in the form of a constitutional amendment, then the spending is allowable. In 2019 the voters approved three billion dollars in additional bonds to fund the Cancer Prevention Institute of Texas. The obvious consequence of this change was the acquisition of a sizable amount of debt by the state. Conveniently, Section 49 contains the language which has provided that authorization, which allows for an understanding of the purposes for the debt.

Limit on Welfare Spending In 1933, during the height of the Great Depression, the national government began to pass a series of laws authorizing matching grant programs for the states. This has always been a source of dispute in Texas since accepting the grants meant that Texas is obligated to pitch in funding, even if it is small in comparison to the federal portion.

An amendment was added to Section 51-a in 1945 to address this. It place limits on the matching grants that were made available to the state to “needy aged, needy blind, and needy children.”26 State spending was capped at thirty-five million dollars, and the maximum monthly payment was capped at twenty million. After a series of amendments increased both caps, the limit was replaced with a cap of no more than one percent of the state budget to be spend on assistance in any biennium. This limit is still in place.

Limit on the Rate of Growth of Appropriations. By the late 1970s, tax payer revolts were common throughout the United States. In Texas these led to the addition of the Tax Relief Amendment, Article 8, Section 22 (Taxation and Revenue). This places limits on the increased spending in successive appropriations bills. The increase cannot exceed the economic growth in the state during that period. The limit is focused primarily on the operating costs of government—what is contained in the General Revenue Fund.

Being a low services state, and given the expansion in the powers of government since the Great Depression, along with the presidency of Lyndon Johnson, concerns were raised that Texas government would become too expansive. Placing limits on the rate of spending was considered an effective way to curtail it. Setting that rate to the growth of the economy seemed a reasonable way to allow for necessary growth, though this restriction did not apply to areas of spending dedicated by the constitution for certain defined areas of spending such as highway construction and the Available School Fund.

Limit on Debt Service. By 1997, the state of Texas commonly issued bonds—as constitutional amendments with the approval of the voters of the state in ratifying elections—to fund defined projects such as highway and prison construction, farm and ranch loans for veterans, and water development projects. These amendments are generally added to Section 49 of Article 3 of the constitution. A perusal through Article 49 allows us to see what those projects have been:

- Veterans’ Land Board, Bond Issues, Veterans’ Land and Housing Funds (49-b);

- Texas Water Development Board, Bond Issue, Texas Water Development Fund

(49-c);

- Development of Reservoirs and Water Facilities, Sale, Transfer, or Lease of

Facilities or Public Waters (49-d);

- Texas Park Development Fund, Bonds) (49-e);

- Bonds for Financial Assistance to Purchase Farm and Ranch Land and for Rural

Economic Development (49-f);

- Superconducting Super Collider Fund (49-g);

- Bond Issuance for Correctional and Statewide Law Enforcement Facilities and for

Institutions for Persons with Intellectual and Development Disabilities (49-h);

- Texas Agricultural Funds, Rural Microenterprise Development Fund (49-i).

In 1997, Section 49-j was added to Article 3 as a response to the increase level of debt carried by the state. A cap was placed on the obligation that the general revenue fund had to service the debt. The limits was set at “five percent of an amount equal to the average of the amount of general revenue fund revenues.”27

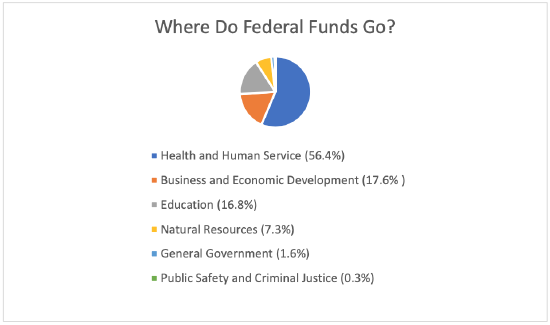

Where Do Federal Funds Go? The total amount of federal funds received by the government of Texas is $86.4 billion. Figure 13.10 shows how that breaks down across areas of spending in the state.

The primary purpose of federal funds is to ensure that the states enforce federal law. These include Social Security, Medicare, unemployment compensation, and disability. States, such as Texas, saw little need to place conditions on who receives these funds. As a result, they come to Texas by being directly placed in the pockets of those eligible for them. Federal funds also come to the state through direct spending on military bases such as Fort Hood, national parks, forests, and monuments, federal offices and employees, as well as money appropriated as a result of natural disasters.28 Recently the state legislature has been wrestling with how to allocate federal stimulus funds it has received due the economic harm caused by the Coronavirus pandemic. These funds are relatively non-controversial.

The same is true for transportation grants and National Highway System Funding. These benefit both intrastate and interstate commerce, meaning that it would be a concurrent power under the constitutional jurisdiction of the national and state governments. Both levels cooperate

to ensure that the transportation systems in place are sufficient to serve the needs of industry and the general population. The goals of the state and the goals of the nation are more or less in sync, despite occasional disputes regarding mass transit and the actual placement and design of highways. Highway project grants are awarded on a competitive basis.29

As discussed earlier in the chapter, other areas of federal spending are very controversial. For example, those related to assistance to the poor. These funds are sent to the state in a variety of forms. These can be matching grants, allocations, payments, or reimbursements. The state is in a position to impose requirements for receiving funds. This process is called means testing. The largest category of federal funding is for Medicaid. Other funds are allocated to local educational agencies, such as the National School Lunch Program, Special Education Basic State Grants, the CHIP, TANF, and the Head Start Program.

What determines the amount of money distributed by the federal government to Texas, or to any state? The amount of funding is not negotiated by a legislature, rather it is determined by a series of formulas that are described in the grants given to the states. Some, such as TANF, are awarded as block grants with few conditions regarding expenditures as long as they have the desired measurable results. Others, such as Head Start, are awarded as categorical grants which are more restrictive.

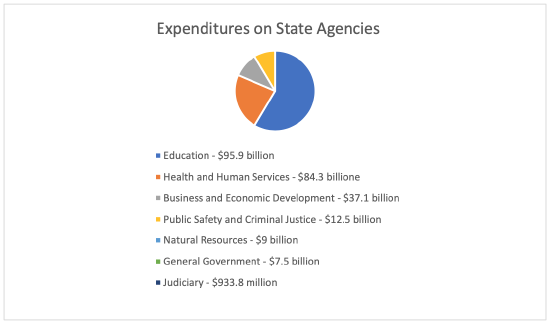

Expenditures for Each Area of Public Policy The amount of spending in the various categories described in the Fiscal Size-Up total $248.3. Figure 13.11 breaks down spending projections from the 2020 – 2021 budget for state agencies.

Agencies of Education This category includes both K-12 (primary and secondary education) and higher education, which includes two year institutions. The bulk of spending is on the former— $64.7 billion—the remainder—$22.7 billion—is on higher education. The most consistent source of funding for education comes from the Permanent School Fund (PSF), which was begun with money contributed from the sale of western lands in 1850, and continues with revenue drawn from further sale of lands, as well as resources are drawn from the land. A similar fund, the Permanent University Fund (PUF), was created to fund two of the state’s public universities— the University of Texas and Texas A&M University. In response to criticism from other state universities, the state created the Higher Education Assistance Fund as an endowment to fund non-PUF institutions.

These figures only reflect the money that is contributed by the state. Funding for K-12 is also drawn from each of the over 1,000 independent school districts throughout the state in the form of property taxes. The fifty community college districts in the state can also draw property taxes, which other general academic institutions cannot. All higher education institutions charge tuition however. Altogether this means that the total amount spent on education in Texas far exceeds what is contributed in state dollars.

But this creates problems. Property taxes are assessed based on a combination of a property’s appraised value and the tax rate set by the elected board of the local government. The amount that can be raised varies from district to district depending on the value of the property in each district. These differences in expenditures have been challenged by poor school districts in both state and federal courts.

As outlined in the chapter 11 on public policy, the United States Supreme Court refused to find that discrepancies in education funding violated the Equal Protection Clause on the Fourteenth Amendment. They noted in San Antonio ISD v. Rodriquez (1973) that a fundamental right to education does not exist in the U.S. Constitution, so there was no constitutional issue to raise.30 But in Edgewood Independent School District v. Kirby (1989), the Texas Supreme Court agreed that the reliance on property taxes, which led to the imbalance, was the result of a lack of sufficient funding by the state of Texas in violation of Article 7 of the Texas Constitution.31 It requires that “the Legislature of the State to establish and make suitable provision for the support and maintenance of an efficient system of public free schools.”32

The decision mandated that the legislature develop a more equitable system of school finance, and in 1993 they would eventually develop the recapture program. Wealthy districts would pay into a fund which would be redistributed to poorer districts. In 2020-2021, 141 school districts paid approximately $1.9 billion to the state for recapture, meaning to redistribute to the poorer districts.. While it has been argued the program helps equalize education in the state, critics contend that the legislature uses these funds to justify reductions in state education funding, freeing them up for other areas of the budget.

Arguments were made that the legislature also violated the Texas Constitution’s requirement for adequate funding when it drastically cut funding to education following the reduction in revenue as a consequence of the 2008 housing crash of the Great Recession.33 The $5.4 billion cut could have been covered by the state’s Rainy Day Fund, but the legislature opted not to draw the money to cover the loss. A lawsuit ensued brought by more than 600 school districts, but the Texas Supreme Court ruled that the cuts did not violate “minimum constitutional requirements” for funding.34

Independent school districts and community college districts are also allowed to sell bonds—if they are authorized by the voters in an election—in order to fund capital projects and the acquisition of property, among a few other things. (Critics have argued that these bonds put schools and communities at risk of insolvency, often pointing out that these bonds are sometimes approved for building relatively frivolous items such as football stadiums. On the other hand, these bonds have allowed school districts in rapidly growing areas such as the suburbs surrounding major population centers to meet the educational needs of their communities.

Given the amount of money spent on education in Texas, the legislature is constantly looking for ways to cuts back on it. Increases in local property values have led to increases in property tax collections. State legislators are attempting to use that additional local revenue to cut back on state spending. In 2020, the legislature has estimated that local property tax increases amount to $5.5 billion. In addition, the state legislature is considering using some of the COVID- 19 relief money allocated to the local school districts, through the state, to offset further state commitments to education funding.35

Health and Human Services With $84.3 billion in expenditures, Health and Human Services (HHS) is the second largest are of spending in Texas. It is not nearly as complex as spending in education. The level of spending is not simply due to a decision by the state, but rather by the national government when it passed the Social Security Amendments of 1965 which created both Medicaid and Medicare. Almost sixty percent of the money spent is from matching grants that the state receives from the national government to implement Medicaid, TANF, and CHIP, among others. Expenditures are based on caseloads for those programs, which in turn is limited to those deemed eligible for assistance.

Total expenditures the are a function of who is eligible, and who applies for the benefits. This is true for Medicaid, TANF, and CHIP. Eligibility is based on income relative to the federal poverty level (FPL), which in 2021 was set at $21,960 for a family of three.36 Eligibility levels vary in Texas based on a number of factors including the age of children and whether a woman who receives Medicaid is pregnant. Generally, Medicaid is only available for people with incomes below the FPL. Incomes can be slightly higher for CHIP. Texas, controversially, remains one of the state’s that has refused to expand Medicaid to 133 percent of the FPL, despite the offer of cost sharing from the federal government that provides a federal matching rate starting at 100 percent and going down no lower than ninety percent.

Business and Economic Development This area of spending is unique in that it includes very little funding from the General Revenue Fund. Of the thirty-seven billion dollars it was budgeted, less than one billion comes from, combined, the General Revenue Fund and the General Revenue – Dedicated Funds. $15.1 billion—forty-one percent of the total—comes from federal funds. $20.8 billion—56.2 percent of the total comes from other funds. The reason is simple. The bulk of the funds are spent building highways and other transportation projects across the state which are funded uniquely.

Public Safety and Criminal Justice Almost all the expenditures on public safety and criminal justice come from the state’s General Revenue Fund (96.2 percent), meaning that it is largely discretionary. Very little is committed to any one areas of spending, as opposed to spending on business and economic development. About half of the revenue spent in this area is on the statewide penitentiary system. Another $2.3 billion is spent on the Department of Public Safety, which is the largest statewide police force in Texas. The rest is split between juvenile justice, the military, and the Alcohol Beverage Commission.

Natural Resources Nearly ten billion dollars is spent on the management of natural resources. Seventy percent of these funds are federal, and 14.5 percent are form Dedicated General Funds. The top recipients of appropriated funds in 2020-2021 are the General Land Office and the Department. Each receives a significant amount of revenue from federal funds. In the case of the Department of Agriculture much of this spending is in the form of child and nutrition programs, and in that of the General Land Office, it was due to disaster recovery efforts.

General Government This section funds the executive branch, with the exception of the regulatory agencies which are listed separately. These include the elected offices of Texas’s plural executive branch. Most funding for these agencies come from the General Revenue Fund, with additional moneys coming from all other funds.

Judiciary Appropriations for the Judiciary come primarily from the General Revenue Fund, and are augmented with funds collected from fees and civil penalties among other sources. The total level of appropriations is responsible for maintaining sixteen separate courts (The Supreme Court, The Court of Criminal Appeals, and fourteen Courts of Appeals) and the salaries of the judges and justices. The costs of district courts are handled by the counties.

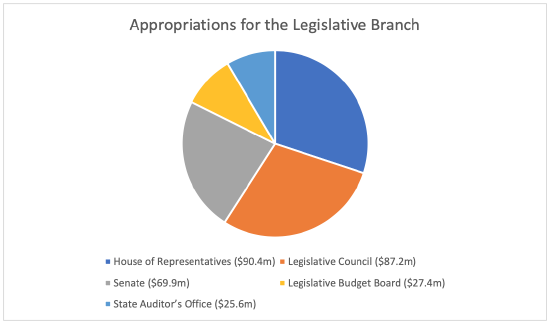

Regulatory The regulatory agencies are a component of the executive branch, and are charged with regulating business in the state. The agencies are designed to focus on specific industries and occupations and are funded largely by those industries and occupations through fees. As discussed in chapter 7 on the executive branch, these agencies are headed by boards composed of people appointed by the governor. By far, the largest agency in the state is the Department of Insurance, with a budget of $271.6 million. Other agencies include the Texas Medical Board, the Texas Board of Nursing, the Texas Racing Commission, and the Public Utility Commission. Legislature The smallest area of appropriations is for the legislative branch. The basic design of the legislature—which includes it meeting only five months every other year and $600 per month pay for legislators. The low overall level of funding for the legislative branch is a reflection of this. Almost all appropriations are drawn from the General Revenue Fund. In addition to the two chambers, the appropriations also fund supporting agencies such as the Legislative Budget Board (the agency responsible for these numbers), the Legislative Council, the Sunset Advisory Commission, and the Legislative Reference Library (Figure 13.12).

15. “Taxes: Gasoline: Who Is Responsible for this Tax?” Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, https://comptroller.texas.gov/taxes/...s/gasoline.php.

16. Transportation Code, “Title 6. Roadways; Subtitle A. Texas Department of Transportation; Chapter 201. General Provisions and Administration; Subchapter A, General Provisions; Sec. 201.002. Operating Expenses; Use of State Highway Fund,” https://statutes.capitol.texas.gov/d...01.htm#201.002.

17. “Hidden Taxes,” in “Be Informed: Taxes,” Just Facts. Seize the Data, https://www.justfacts.com/taxes.asp.

18. “Texas Liquor, Wine, and Beer Tax,” Sales Tax Handbook, https://www.salestaxhandbook.com/tex...0liquor%20sold.

19. Josh Haney, “The (Long, Long) History of the Texas Property Tax, A Controversial Levy,” Fiscal Notes, Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, Oct. 2015, https://comptroller.texas.gov/econom...er/proptax.php.

20. Legislative Budget Board, “2. Revenue Sources and Economic Indicators,” Fiscal Size-Up 2020-21 Biennium, p. 35, https://www.lbb.state.tx.us/Document...izeUp_2020-pdf.

21. SJR 18, 66th Regular Session, Legislative Reference Library of Texas, https://lrl.texas.gov/legis/billsear...umberDetail=18.

22. Legislative Budget Board, “Revenue Sources and Economic Indicators,” Fiscal Size-Up 2020–21 Biennium, May 2020, p. 43, https://lbb.state.tx.us/Documents/Pu...cal_SizeUp.pdf.

23. “Budget Drivers: The Forces Driving State Spending, Classifying State Revenue,” Fiscal Notes, State Comptroller of Public Accounts, Nov. 2018, https://comptroller.texas.gov/econom...2018/november/.

24. T.J, Costello, David Green, and Patrick Graves, “The Texas Economic Stabilization Fund, Saving for Rainy Days,” Fiscal Notes, Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, https://comptroller.texas.gov/econom.../rainy-day.php.

25. HJR 2, 70th Regular Session, amends Tex. Const. art. III, §49-g, Nov. 8, 1988, https://statutes.capitol.texas.gov/D...N.3.htm#3.49-g.

26. Tex. Const. art. III, §51-a, amended Nov. 5, 1945, Legislative Reference Library of Texas, https://lrl.texas.gov/legis/billsear...mendmentID=221.

27. Tex Const. art III, added §49-j, 1997.

28. Kevin McPherson and Bruce Wright, “Federal Funding in Texas,” Fiscal Notes, Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, Nov. 2017, https://comptroller.texas.gov/econom...%20that%20year.

29. “A Guide to Federal-Aid Programs and Projects,” Federal Highway Administration, May 1999, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/programadmin/if99006.cfm.

30. San Antonio Independent School District et al., Apellants, v. Demetrio P. Rodriguez, 411 US 1 (1973), Legal Information Institute [LII], Cornell Law School, https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/411/1

31. Edgewood ISD v. Kirby, The Texas Politics Project, https://texaspolitics.utexas.edu/edu...od-isd-v-kirby.

32. Tex. Const. art. VII, § 1, https://statutes.capitol.texas.gov/D...N/htm/CN.7.htm.

33. “The Past Decade in Texas School Finance,” Texas School Coalition, Jan. 10, 2020, https://www.txsc.org/the-past-decade...chool-finance/.

34. Justice Don Willet, opinion quoted in Kiah Collier, “Texas Supreme Court Rules School Funding System is Constitutional,” Texas Tribune, May 13, 2016, https://www.texastribune.org/2016/05...inance-ruling/

35. Ross Ramsey, “Analysis: A $5.5 Billion Shift in Who Pays for Public Education in Texas,” Texas Tribune, Apr. 9, 2021, https://www.texastribune.org/2021/04...roperty-taxes/.

36. Kimberly Amadeo, “Federal Poverty Level Guidelines and Chart,” Balance, Mar. 31, 2021, https://www.thebalance.com/federal-p...-chart-3305843.