13.3: Differences of Sexual Development

- Page ID

- 110547

This page is a draft and under active development. Please forward any questions, comments, and/or feedback to the ASCCC OERI (oeri@asccc.org).

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Identify the basic characteristics of the most common sex chromosome abnormalities (Turner Syndrome and Klinefelter Syndrome).

- Understand the term intersex and the various conditions it encompasses.

- Explain the role of hormones in the development of anomalous sexual differentiation for XX individuals with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) and XY individuals with androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS).

- Explain how David Reimer's case challenged Dr. John Money's theory of psychosexual neutrality.

Overview

This section discusses some of the many ways in which sexual development can differ from typical XX/male and XY/female formats. Note that while the scientific literature on this topic typically labels these conditions "Disorders of Sexual Development (DSD)", we prefer to refer to them as "Differences of Sexual Development". Chromosomal abnormalities (such as Triple X syndrome, Turner syndrome, and Klinefelter syndrome), intersex conditions, anomalous female differentiation (such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia) and anomalous male sexual differentiation (such as 5α-reductase deficiency and androgen insensitivity syndrome) demonstrate some of the diverse variations of biological sex found in humans. The case of David Reimer illustrates that raising a typically-developed biological male (who lost his penis in infancy due to a circumcision accident) as a girl can fail catastrophically.

Chromosomal Abnormalities

Aneuploidy

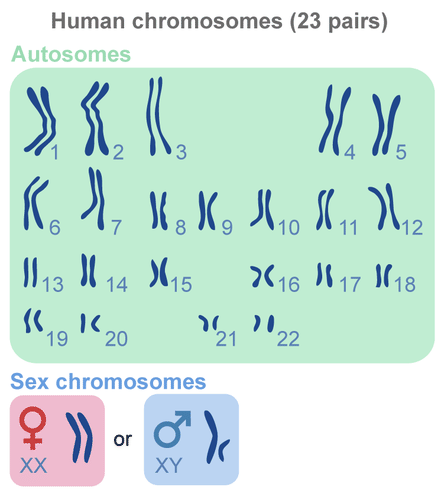

As discussed in the chapter on genetics, a typical human individual has 22 pairs of autosomes ("self" chromosomes) and one pair of sex chromosomes (either XX for females or XY for males), resulting in a total of 46 chromosomes (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

Sometimes errors occur during the formation of the gametes (eggs in females and sperm in males), resulting in missing chromosomes or extra chromosomes. When an individual inherits too many or two few chromosomes, it is called a chromosomal abnormality. (Or, more specifically, aneuploidy- the presence of an abnormal number of chromosomes in a cell.) The most common cause of chromosomal abnormalities is older age of the mother. As a female ages, the immature eggs in her ovaries (which have been present since before birth, unlike the sperm cells in males) are more likely to suffer damage due to longer term exposure to environmental factors. Consequently, some gametes do not divide evenly when they are forming, and some eggs have more (or less) than 23 chromosomes. Often when the error includes one of the autosomes, the resulting zygote (fertilized egg) is not viable. In fact, it is believed that close to half of all zygotes have an abnormal number of chromosomes. Most of these zygotes fail to develop and are spontaneously aborted by the body of the mother (often without her knowledge that conception ever occurred).

One of the few chromosomal abnormalities that more commonly survives (to birth and decades beyond) is Down syndrome (trisomy 21- three copies of chromosome number 21). In addition to some degree of intellectual disability and characteristic facial features, affected individuals often have heart defects and other health problems. The overall occurrence of Down Syndrome is one in every 691 births, but it increases to one in every 300 births for women aged 35 and older.

Interestingly, chromosomal errors involving the sex chromosomes (the 23rd pair), called sex chromosome aneuploidy, are less lethal. The exception is having only a single Y chromosome- there are many important genes on the X chromosome, so a zygote with only one Y chromosome (and no X chromosome) will not survive. At least 1 in every 1,000 conceptions results in a variation of chromosomal sex beyond the typical XX or XY sets. Some of these variations include XXX (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)), XYY, XXY, or even a single X (Dreger, 1998).

Some individuals with atypical sex chromosomes may have unusual physical characteristics, such as being taller than average, having a thick neck, or being sterile (unable to reproduce); but in many cases, these individuals have no cognitive, physical, or sexual issues (Wisniewski et al., 2000). These sex-linked chromosomal disorders are briefly described in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\). It is even possible to have four or more sex chromosomes (XXXX, XXYY, XXXYY, etc.).

| Disorder | Sex Appearance & Fertility | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Turner Syndrome (XO) | Female, but immature (infertile) | Affects cognitive functioning and sexual maturation; short stature may be noted. |

| Klinefelter Syndrome (XXY) | Male, may have some breast development (often infertile) | The Y chromosome stimulates the growth of male genitalia, but the additional X chromosome inhibits this development (may have low levels of testosterone). |

| Supermale Syndrome (XYY) | Male (usually normal fertility) | Few symptoms, which may include being taller than average, acne, and an increased risk of learning problems. Generally otherwise normal. |

| Triple X Syndrome (XXX) | Female (usually normal fertility) | May result in being taller than average, having learning difficulties, decreased muscle tone, seizures, and kidney problems. |

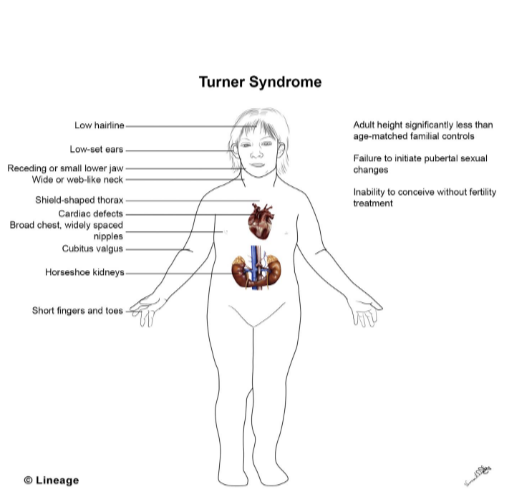

The more common of these sex chromosome disorders are Turner Syndrome and Klinefelter Syndrome. Turner Syndrome occurs when one of the X chromosomes is missing or damaged and the resulting zygote has XO sex chromosomes. This occurs in 1 of every 2,500 live female births (Carroll, 2007) and affects the individual’s cognitive functioning and sexual maturation. The external genitalia appear normal, but breasts and ovaries do not develop fully and the woman does not menstruate. Turner’s syndrome also results in short stature and other physical characteristics, such as a webbed neck, shield-shaped thorax, and cardiac defects. Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) illustrates the symptoms of Turner's syndrome and Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) shows pictures of 18 individuals of Asian descent with Turner's syndrome.

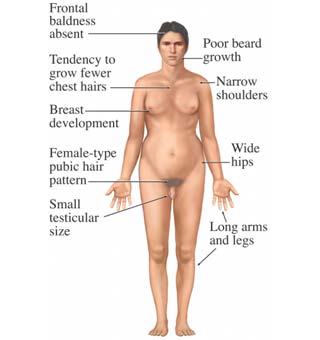

Klinefelter Syndrome (XXY) results when an extra X chromosome is present in the cells of a male and occurs in 1 out of 700 live male births. The Y chromosome stimulates the growth of male genitalia, but the additional X chromosome inhibits this development. An individual with Klinefelter Syndrome often has some breast development, wide hips, infertility (this is the most common cause of infertility in males), small testicular size, and low levels of testosterone (National Institutes of Health, 2019). Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) illustrates the symptoms of Klinefelter's syndrome on the left and a 29 year old male with Klinefelter`s syndrome who is undergoing testosterone treatment on the right. Regular testosterone injections can promote strength and facial hair growth, build a more muscular body type, increase sexual desire, and enlarge the testes.

Other Chromosomal Alterations

As mentioned in Section 13.2, the SRY gene on the Y chromosome is the gene that directs development of the testes (typically leading to male reproductive structure development). Occasionally during sperm formation the SRY gene can cross over from the Y chromosome to the X chromosome. (Gene cross over regularly occurs between the 22 autosomes during the formation of gametes, but usually does not occur between the X and Y chromosomes, since they do not have the same genes.) If a sperm carrying a Y chromosome that has lost its SRY gene fertilizes an egg, although chromosomally genetically male (XY), the resulting embryo will not form testes and consequently will not develop male reproductive structures. (For mammals, female development is the "default" in the absence of hormones.) Likewise, if a sperm carrying an X chromosome that has an SRY gene attached to it fertilizes an egg, although chromosomally genetically female (XX), the resulting embryo will develop testes (which will then produce testosterone) and reproductive structures will develop in a male pattern. The individual will be infertile, however, since other genes on the Y chromosome are necessary for viable sperm production. This is another way in which abnormalities on the X or Y chromosomes (rather than having entire chromosomes that are extra or missing) produce variations in human sex characteristics.

Variations in Reproductive Structures

Intersex Conditions

In cases where hormones are not produced (or responded to) following the two most common patterns, a fetus may develop biological characteristics in between typical male and typical female structures. These people are considered to have intersex conditions. According to the Intersex Society of North America, intersex is a general term used for a variety of conditions in which a person is born with a reproductive or sexual anatomy that doesn’t fit the typical definitions of male or female. For example, a person might be born appearing to be male on the outside, but having mostly female-typical anatomy on the inside. Or a person may be born with genitals that seem to be intermediate between the usual male and female types—for example, a girl may be born with a notably large clitoris, or lacking a vaginal opening, or a boy may be born with a micropenis, or with a scrotum that is divided so that it has formed more like labia. Some people have mosaic genetics, meaning that two separate sets of chromosomes merged into one individual early in embryonic development. Any given body cell will contain one set or the other, and if all cells have either XX chromosomes or XY chromosomes, the condition may never even be detected. However, if some of their cells have XX chromosomes and some of them have XY chromosomes, separate areas of the body may have developed differently as a result. For example, a person may have an ovary on one side of the body and a testis on the other side. This is the true meaning of the word "hermaphrodite"- having both male and female gonadal tissue in the same body. (It is also possible to have a mixture of ovarian and testicular tissue in the gonads.) The intersex conditions discussed below are sometimes called "pseudohermaphrodites"- having something similar to both male and female anatomical structures in the same body (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)).

Though intersex is commonly thought of as an inborn condition, intersex anatomy isn’t always apparent at birth. Some intersex traits are not recognizable until puberty or later in life (interACT 2021), or never even realized at all. Sometimes a person isn’t found to have intersex anatomy until they reach the age of puberty, or find themselves to be infertile as an adult, or die of old age and are autopsied. Some people live and die with intersex anatomy without anyone (including themselves) ever knowing. Which variations of sexual anatomy count as intersex? In practice, different people have different answers to that question. That’s not surprising, because intersex isn’t a discrete category. Nature presents us with a spectrum of sexual anatomy. Breasts, penises, clitorises, scrotums, labia, gonads—all of these vary in size and shape and morphology. However, in human cultures, sex categories generally get simplified into male or female, sometimes with "intersex", "third sex" or "two spirit" included as an "other" option.

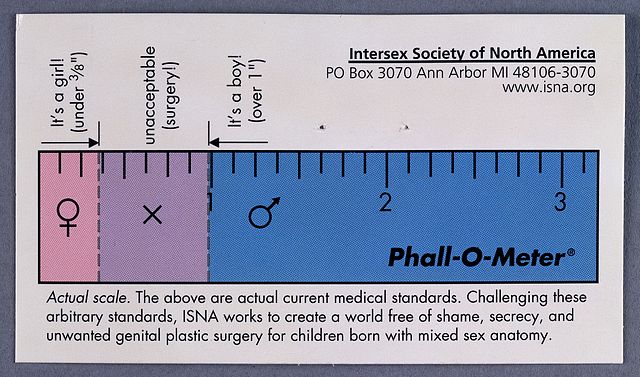

So nature doesn’t determine where the category of “male” ends and the category of “intersex” begins, or where the category of “intersex” ends and the category of “female” begins. Humans decide. Humans (typically doctors today, at least in Western cultures) decide how small a penis has to be, or how unusual a combination of parts has to be, before it counts as intersex. Humans decide whether a person with XXY chromosomes or XY chromosomes and androgen insensitivity will count as intersex. Doctors’ opinions about what should count as intersex vary substantially. Some think you have to have “ambiguous genitalia” to count as intersex, even if your inside is mostly of one sex and your outside is mostly of another. Some think your brain has to be exposed to an unusual mix of hormones prenatally to count as intersex—so that even if you’re born with atypical genitalia, you’re not intersex unless your brain experienced atypical development. And some think you have to have both ovarian and testicular tissue (be a true hermaphrodite- very rare!) to count as intersex. Intersex and transgender (having a gender identity that does not match your assigned birth sex) are not interchangeable terms; many transgender people have no intersex traits, and many intersex people do not consider themselves transgender.

According to the Intersex Society of North America, it is up to the individual to decide if they "count" as intersex. However, since some forms of intersex signal underlying metabolic concerns, a person who thinks they might be intersex should seek a diagnosis and find out if they need professional healthcare. Everyone, regardless of their sexual anatomy, should be free of shame, secrecy, and unwanted genital surgeries, even if someone else believes they have non-standard sexual anatomy. It used to be standard practice to surgically alter any newborn who didn't quite fit to the typical "male" or "female" body pattern, which often meant attempting to make the child look more like a typical girl (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). Although that is much easier surgically, gender identity confusion, loss of sexual sensation, and possibly unsatisfactory future sexual relationships are unfortunate possible outcomes. Current recommendations are to simply leave the child alone and see where development takes them, being prepared for any possible combinations of gender expression and sexual orientation. If desired, the individual can choose genital reconstruction surgery for themselves when they are old enough to understand and consent to the procedure.

Anomalous Female Sexual Differentiation

By studying individuals who do not neatly fall into the dichotic boxes of female or male and for whom the process of sexual differentiation is atypical, behavioral endocrinologists glean hints about the process of typical sexual differentiation. Prenatal exposure to androgens is the most common cause of anomalous sexual differentiation among females. The source of androgen may be internal (e.g., secreted by the adrenal glands- endocrine glands located on top of the kidneys) or external (e.g., exposure to environmental estrogens). One case of prenatal exposure to internal androgens is congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH). CAH develops when an enzyme needed to produce cortisol is defective or missing, resulting in abnormal hormonal feedback which leads to excessive production of androgens by the adrenal cortex. In a female (XX) fetus, the elevated androgen levels caused by CAH result in varying degrees of masculinization of the external genitalia. As a result, the baby's sex may appear ambiguous or may even be mistaken as male. CAH is the most common cause of intersex conditions.

Although the effects of CAH on anatomical development are more noticeable in biological females, males can also inherit CAH. If a male (XY) fetus has CAH, his prenatal body development is similar to other males. However, he is likely to show precocious (early) sexual development as a result of the excessive androgens, such as enlargement of the penis and facial hair as a toddler (Jones & Lopez, 2006).

Anomalous Male Sexual Differentiation

Female mammals are considered the “neutral” sex; additional physiological steps are required for male differentiation, and more steps bring more possibilities for errors in differentiation. One example of male anomalous sexual differentiation (seen in Dominican Republic populations) is Guevedoces syndrome ("eggs at twelve") or 5α-reductase deficiency. Individuals with 5α-reductase deficiency are genetic males (XY) with testes that produce testosterone and cells that respond to androgens. However, because they lack the enzyme 5α-reductase, which converts testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, they are born with ambiguous genitalia and are raised as females. As mentioned in Section 13.2, dihydrotestosterone is required for typical prenatal development of the penis and scrotum. The high levels of testosterone occurring during puberty result in recognizable masculinization of the body. The "girls" become boys in dress and behavior and generally have heterosexual orientations (Jones & Lopez, 2006). In other words, these individuals readily transition to a masculine gender identity and are attracted to women.

Another example of male anomalous sexual differentiation is androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS). Individuals with AIS lack receptors for androgens and develop as females. Androgen insensitivity syndrome is an example of an endocrine disorder where an endocrine gland secretes a typical amount of hormone, but target cells do not respond normally to it. Individuals with AIS are genetically male and have an X and a Y chromosome, but they develop and are raised as females. This is due to a mutation in the androgen receptor gene which is located on the X chromosome. The androgen hormone testosterone normally causes the testes to descend and typical male characteristics to develop.

People with AIS have the external sex characteristics of females; they are typically raised as females and have a female gender identity. Affected individuals have male gonads (testes) that are undescended, which means they are located in the pelvis or abdomen (instead of inside a scrotum hanging between the legs). However, these individuals have neither female nor male internal reproductive structures. During prenatal development, the testes produced Mullerian inhibiting substance, which caused the duct system that would form female internal sex organs to degenerate. Thus, these individuals do not have a uterus and do not menstruate. Without ovaries, Fallopian tubes, or a uterus, they are infertile and thus unable to conceive a child. Since the Wolffian ducts (that form male internal sex organs) require testosterone to develop, they also degenerate prenatally. The testes did (and do) produce testosterone, but since the body cells lack receptors for androgens, male development does not occur.

Conclusion: Variations in Biological Sex

"Although male and female are the most typical biologically ordained poles of sexual identity, a vast number of gradations can be produced by normally occurring variations in the underlying hormonal control mechanisms that guide gender differentiation" (Panksepp, 2004, page 234). In humans, intersex individuals make up about two percent—more than 150 million people—of the world’s population (Blackless et al., 2000). There are dozens of conditions that can lead to intersex anatomical variations, such as Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome and Turner’s Syndrome (Lee et al., 2006). The term “syndrome” can be misleading; although intersex individuals may have physical limitations (e.g., about a third of Turner’s individuals have heart defects; Matura et al., 2007), they otherwise lead relatively normal intellectual, personal, and social lives. In any case, intersex individuals demonstrate the diverse variations of biological sex.

The Case of David Reimer

In August of 1965, Janet and Ronald

Dr. Money had spent a considerable amount of time researching transgendered individuals and individuals born with ambiguous genitalia. As a result of this work, he developed a theory of psychosexual neutrality. His theory asserted that we are essentially neutral at birth with regard to our gender identity and that we don’t assume a concrete gender identity until we begin to master language. Furthermore, Dr. Money believed that the way in which we are socialized in early life is ultimately much more important than our biology in determining our gender identity (Money, 1962).

Dr. Money encouraged Janet and Ronald to bring the twins to Johns Hopkins University, and he convinced them that they should raise Bruce as a girl. Left with few other options at the time, Janet and Ronald agreed to have Bruce’s testicles removed and to raise him as a girl. When they returned home to Canada, they brought with them Brian and his “sister,” Brenda, along with specific instructions to never reveal to Brenda that she had been born a boy (Colapinto, 2000).

Early on, Dr. Money shared with the scientific community the great success of this natural experiment that seemed to fully support his theory of psychosexual neutrality (Money, 1975). Indeed, in early interviews with the children it appeared that Brenda was a typical little girl who liked to play with “girly” toys and do “girly” things.

However, Dr. Money was less than forthcoming with information that seemed to argue against the success of the case. In reality, Brenda’s parents were constantly concerned that their "daughter" wasn’t really behaving as most girls did, and by the time Brenda was nearing adolescence, it was painfully obvious to the family that Brenda was really having a hard time identifying as a female. In addition, Brenda was becoming increasingly reluctant to continue the visits with Dr. Money to the point that Brenda threatened suicide if she ever saw him again.

At that point, Janet and Ronald disclosed the true nature of Brenda’s early childhood to their children. While initially shocked, Brenda reported that things made more sense now, and ultimately, decided to identify as a male, choosing the name

This sad story speaks to the complexities involved in gender identity. While the

Summary

Although the scientific literature regarding sexual development that differs from typical XX/male and XY/female formats refers to these conditions as "Disorders of Sexual Development (DSD)", we use "Differences of Sexual Development" in this chapter. It is called a chromosomal abnormality (or aneuploidy) when an individual inherits too many or two few chromosomes, typically as a result of an error during gamete (egg or sperm) formation in one (or both) of the parents. The most common aneuploidies of the sex chromosomes (X and Y) include Triple X syndrome (XXX), Supermale syndrome (XYY), Klinefelter syndrome (XXY), and Turner syndrome (XO). (A zygote that inherits only one Y chromosome and no X chromosome is spontaneously aborted.) While individuals with Klinefelter syndrome and Turner syndrome usually have visible anatomical differences and are often infertile, individuals with Triple X syndrome and Supermale syndrome may have no noticeable symptoms and usually have normal fertility. Another chromosomal alteration that affects sexual development is the transfer of the SRY gene from the Y chromosome to the X chromosome. A zygote with a Y chromosome that has lost its SRY gene will develop in the "default" female pattern (since the gonads will not develop as testes without an SRY gene), and a zygote with an X chromosome that has the SRY gene attached to it will develop in a male pattern, but will not be fertile.

When an individual develops biological characteristics that are in between typical male and typical female structures during prenatal development, they are said to have an intersex condition. There are many anatomical and physiological variations which fit under this umbrella term, and there is no current consensus on what "counts" as intersex and what does not. The Intersex Society of North America states that it is up to the individual to decide if they "count" as intersex, and that everyone, regardless of their sexual anatomy, should be free of shame, secrecy, and unwanted genital surgeries. While immediate surgery to try to create a more typical (usually female) appearance used to be common practice, current recommendations are to simply leave the intersex child alone and see where development takes them, being prepared for any possible combinations of gender expression and sexual orientation. Although intersex individuals may have physical limitations, they otherwise lead relatively normal intellectual, personal, and social lives.

Prenatal exposure to androgens is the most common cause of anomalous sexual differentiation among females. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) develops when excessive production of androgens by the adrenal cortex occurs due to a missing enzyme. In a female (XX) fetus, the elevated androgen levels result in varying degrees of masculinization of the external genitalia. As a result, the baby's sex may appear ambiguous or may even be mistaken as male. CAH is the most common cause of intersex conditions.

Androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS) and 5α-reductase deficiency are the most common causes of anomalous male (XY) sexual differentiation. People with AIS have the external sex characteristics of females and they are typically raised as females and have a female gender identity. However, they are infertile because they do not have female internal structures and their gonads are testes rather than ovaries. Although their testes produce testosterone, their body cells lack testosterone receptors and thus do not respond accordingly. Individuals with 5α-reductase deficiency are born with ambiguous genitalia and are raised as females. During puberty, high levels of testosterone result in recognizable masculinization of the body, and these individuals usually transition to male gender identities and are generally attracted to women.

David Reimer was one of a pair of identical twin boys born in Canada in August 1965 (birth name Bruce). As a result of a tragic circumcision accident in infancy, his penis was destroyed, and he was raised as "Brenda" under the advice of Dr. John Money, who erroneously believed that gender identity was exclusively determined by experiences during childhood development. By early adolescence, it was clear that Brenda was having difficulties identifying as a girl, and the truth was revealed to Brenda and "her" twin brother Brian by their parents. Brenda returned to a masculine gender identity, choosing the name David, and initially his life was going well. In the early 2000s, after discovering that Dr. Money was still touting the "experiment" as a success, the Reimer family went public with their story. Ultimately a number of unfortunate events (including the death of Brian due to a drug overdose) led to David's suicide in 2004. The truth of this story (which had originally been used to support decisions to reassign the gender of intersex children at birth) made the scientific and medical communities more cautious in dealing with cases that involve intersex children and how to deal with their unique circumstances.

References

Note: These references are specifically those added to the content of this page by Naomi Bahm and do not include citations from the outside sources used. Refer to the text attributions to locate citations for articles from other sources.

Jones, R.E. & Lopez, K.H. (2006) Human Reproductive Biology, 3rd edition. Academic Press.

Panksepp, J. (2004). Affective neuroscience: The foundations of human and animal emotions; Chapter 12: The varieties of love and lust: Neural control of sexuality. Oxford University Press.

Additional Resources

Chromosomal Abnormalities- Video link from Wakim & Grewal textbook: https://youtu.be/jhHGCvMlrb0

Emily Quinn is an artist and activist. In this video, she talks about the hardship that she experienced while growing up as an individual with Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome.

Websites for specific conditions:

- XO: https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseas...rner-syndrome/

- XXY: https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseas...lter-syndrome/

- XXX: https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/trisomy-x/

- XYY:

- AIS: https://rarediseases.org/gard-rare-d...vity-syndrome/

- CAH: https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseas...l-hyperplasia/

- Guevodoces:

Intersex Society of North America: https://isna.org/

Attributions

- Figures:

- Chromosomes by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal (LadyofHats), CC BY-NC 3.0, for CK-12

- XXXSyndromeB By Nicole R Tartaglia, Susan Howell, Ashley Sutherland, Rebecca Wilson, and Lennie Wilson - https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2883963/, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/inde...curid=5022965

- A girl with Turner's syndrome by Sküskü15, licensed CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

- Individuals of Asian descent with Turner's syndrome by Paul Kruszka, Yonit A Addissie, Cedrik Tekendo-Ngongang, Kelly L Jones, Sarah K Savage, Neerja Gupta, Nirmala D Sirisena, Vajira H W Dissanayake, C Sampath Paththinige, Teresa Aravena, Sheela Nampoothiri, Dhanya Yesodharan, Katta M Girisha, Siddaramappa Jagdish Patil, Saumya Shekhar Jamuar, Jasmine Chew-Yin Goh, Agustini Utari, Nydia Sihombing, Rupesh Mishra, Neer Shoba Chitrakar, Brenda C Iriele, Ezana Lulseged, Andre Megarbane, Annette Uwineza, Elizabeth Eberechi Oyenusi, Oluwarotimi Bolaji Olopade, Olufemi Adetola Fasanmade, Milagros M Duenas-Roque, Meow-Keong Thong, Joanna Y L Tung, Gary T K Mok, Nicole Fleischer, Godfrey M Rwegerera, María Beatriz de Herreros, Johnathan Watts, Karen Fieggen, Victoria Huckstadt, Angélica Moresco, María Gabriela Obregon, Dalia Farouk Hussen, Neveen A Ashaat, Engy A Ashaat, Brian H Y Chung, Eben Badoe, Sultana M H Faradz, Mona O El Ruby, Vorasuk Shotelersuk, Ambroise Wonkam, Ekanem Nsikak Ekure, Shubha R Phadke, Antonio Richieri-Costa, Maximilian Muenke, is in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- [Left image] The symptoms of Klinefelter's syndrome in a human male By http://smithperiod6.wikispaces.com/K...ter's+Syndrome, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/inde...curid=25557422 AND [right image] Klinefelter's syndrome By CDL69 - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/inde...curid=18683822

- Wax human hermaphrodite genitals by Daniel Ullrich, Threedots, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Phall-O-Meter (Intersex Society of North America) by Wellcome Images, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International, via Wikimedia Commons

- Text adapted from:

- "Genetics of Inheritance" by Suzanne Wakim & Mandeep Grewal, LibreTexts is licensed under CC BY-NC.

- " Chromosomal Abnormalities" by Martha Lally & Suzanne Valentine-French, LibreTexts is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA. From textbook Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

- " Heredity" by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, LibreTexts is licensed under CC BY./@go/page/10183

- Human Sexual Anatomy and Physiology by Don Lucas and Jennifer Fox, licensed CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 via Noba Project.

- The Psychology of Human Sexuality by Don Lucas and Jennifer Fox, licensed CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 via Noba Project.

- Intersex Conditions section (somewhat modified): "The Interplay of Sex and Gender" by LibreTexts is licensed under notset.

- CAH (partial): "Genetics Teacher Preparation Notes" by LibreTexts is licensed under CC BY-NC.

- Hormones & Behavior by Randy J. Nelson, licensed CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 via Noba Project.

- "Introduction to the Endocrine System" by Suzanne Wakim & Mandeep Grewal, LibreTexts is licensed under CC BY-NC.

- David Reimer story, a few phrases in Intersex Conditions: 10.3 Sexual Behavior (Psychology 2e) by Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, and Marilyn D. Lovett, licensed CC BY 4.0 via OpenStax.

- Changes: Text (and some images) from above ten sources pieced together with some modifications, transitions and additional content (particularly much of the Aneuploidy and Other Chromosomal Alterations sections) added by Naomi I. Gribneau Bahm, PhD., Psychology Professor at Cosumnes River College, Sacramento, CA.