13.5: Sexual Orientation

- Page ID

- 142984

This page is a draft and under active development. Please forward any questions, comments, and/or feedback to the ASCCC OERI (oeri@asccc.org).

- Understand Kinsey's continuum of sexual orientation and the range of sexual orientation labels used now

- Explain the evidence for at least two nonsocial causes of sexual orientation

Overview

This section discusses sexual orientation, a person's emotional and sexual attraction to other individuals of a particular sex or gender. Kinsey's continuum of sexual orientation (a range from exclusively heterosexual through equally bisexual to exclusively homosexual) is introduced, as well as some additional terms that are in contemporary use (polysexual, pansexual, and asexual). The development and origins of sexual orientation are addressed, including research exploring genetics, prenatal hormone exposure, the fraternal-birth-order effect, and childhood development. Regardless of the root cause(s) for a person's sexual orientation (and/or gender identity), it is not a conscious choice and cannot be easily changed.

Sexual Orientation

A person's sexual orientation is their emotional and sexual attraction to a particular sex or gender, including a continuing pattern of romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of a given sex or gender. According to the American Psychological Association (APA) (2016), sexual orientation also refers to a person's sense of identity based on those attractions, related behaviors, and membership in a community of others who share those attractions. Although a person’s intimate behavior may have sexual fluidity- changing due to circumstances (Diamond, 2009)- sexual orientations are relatively stable over one’s lifespan, and are influenced by genetics (Frankowski, 2004). Sexual orientation is distinct and independent from both biological sex and gender, as discussed in Section 13.4.

While some argue that sexual attraction is primarily driven by reproduction (e.g., Geary, 1998), empirical studies point to pleasure as the primary force behind our sex drive. For example, in a survey of college students who were asked, “Why do people have sex?” respondents gave more than 230 unique responses, most of which were related to pleasure rather than reproduction (Meston & Buss, 2007). Here’s a thought-experiment to further demonstrate how reproduction has relatively little to do with driving sexual attraction: Add the number of times you’ve had and/or hope to have sex during your lifetime. With this number in mind, consider how many times the goal was (or will be) for reproduction versus how many it was (or will be) for pleasure. Which number is greater?

A Continuum of Sexual Orientation

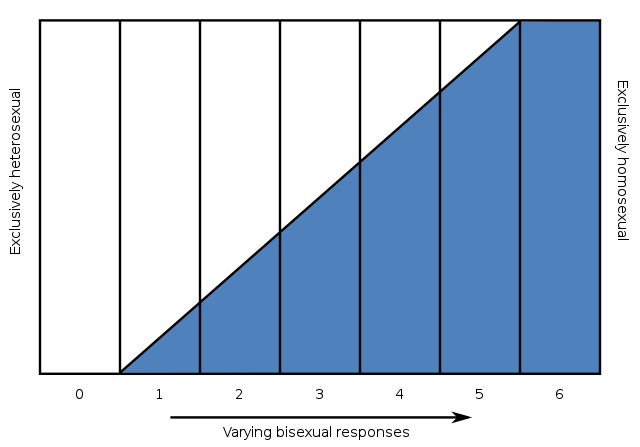

Instead of thinking of sexual orientation as being two dichotomous categories- homosexual (attracted to the same sex, Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)) and heterosexual (attracted to the opposite sex)- sexuality researcher Alfred Kinsey and colleagues argued that it is a continuum (Kinsey, Pomeroy, & Martin, 1948). They measured sexual orientation using a seven-point scale called the Heterosexual-Homosexual Rating Scale (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)), in which zero is exclusively heterosexual, three is bisexual (with equal attractions to the same and opposite sexes), and six is exclusively homosexual. Research done over several decades has supported this idea that sexual orientation ranges along a continuum, from exclusive attraction to the opposite sex/gender to exclusive attraction to the same sex/gender (Carroll, 2016).

The commonly stated notion that “10% of people are homosexual” originates (erroneously) from Kinsey’s 1948 study, which found that 10% of men reported being exclusively homosexual for at least three years during adulthood. In addition to the likelihood that Kinsey’s sample overestimated the actual occurrence of homosexuality in the population, only 4% of the male respondents in his study reported being homosexual their entire lifetime. This figure is much closer to the 3.5% prevalence of non-heterosexual (gay/lesbian/bisexual) orientation found in more recent and representative studies of US and other Western populations (Bailey et al., 2016). However, it is important to note that how a respondent is asked to report their sexual orientation produces very different results. Researchers using the Kinsey Scale have found 18% to 39% of Europeans and Americans identifying as somewhere between heterosexual and homosexual (Lucas et al., 2017; YouGov.com, 2015). These percentages drop dramatically to only 0.5% to 1.9% non-heterosexual when researchers force individuals to respond using only two categories (Copen, Chandra, & Febo-Vazquez, 2016; Gates, 2011).

Although the percentage of US adults identifying as LGBT (lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender) remained relatively stable through the early 2010s (and still remains stable in older-aged cohorts), there is evidence that younger people are more likely to identify as LGBT than previous generations, which is in turn increasing the overall prevalence in the population. Gates (2017, page 1221) reports that “the percentage of older age cohorts identifying as LGBT has remained stable or declined despite large increases among Millennials, who are now three times more likely than Baby Boomers to identify as LGBT (7.3% vs 2.4%).” (Millennials are people born during the years 1981 through 1996 and Baby Boomers are people born during the years 1946 through 1964 (Dimock, 2019).)

Indeed, even beyond a continuum from heterosexual to homosexual, sexual orientation is as diverse as gender identity. Some examples of sexual orientation include heterosexuality (attraction to the opposite sex/gender), homosexuality (attraction to the same sex/gender, also referred to as same-sex attraction- some people find the term homosexuality offensive since it was previously classified as a mental illness), bisexuality (attraction to two sexes/genders), polysexuality (attraction to multiple sexes/genders), pansexuality (attraction to all sexes/genders), and asexuality (no sexual attraction to any sex/gender).

Development and Origins of Sexual Orientation

Genetics

Prenatal Hormone Exposure

Fraternal-Birth-Order Effect

Childhood Development

Two other forms of evidence supporting non-social causes of sexual orientation, particularly for males, are related to childhood development and behavior: gender nonconformity and outcomes from attempts to alter gender identity. Children who display gender nonconformity by not following the roles that society expects (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)) are more likely to be homosexual as adults. This is a robust finding across cultures, but applies much more strongly to boys than girls. Additionally, "when infant boys are surgically and socially “changed” into girls, their eventual sexual orientation is unchanged (i.e., they remain sexually attracted to females)" (Bailey et al., 2016, page 46). This "natural experiment" is most commonly the result of irreparable damage to the penis, as was the case with David Reimer (see the section on differences of sexual development).

In Closing: Gender and Sexual Orientation

Summary

Sexual orientation is an individual's emotional and sexual attraction to a particular sex or gender, including their sense of identity based on those attractions and related behaviors. A person may exhibit sexual fluidity (with attractions and behaviors changing due to circumstances), but sexual orientations tend to be relatively stable over the lifespan. Some argue that sexual attraction is primarily driven by reproduction, but empirical studies suggest that pleasure is the primary force behind our sex drive, and that reproduction has relatively little to do with it.

Arguing that dividing people into homosexual and heterosexual did not capture the breadth of human sexual orientation, Kinsey created a continuum with a seven-point scale called the Heterosexual-Homosexual Rating Scale. Zero is exclusively heterosexual, three is bisexual (with equal attractions to the same and opposite sexes), and six is exclusively homosexual. Subsequent research has supported this idea that sexual orientation ranges along a continuum. Representative studies of US and other Western populations report a 3.5% prevalence of non-heterosexual (gay/lesbian/bisexual) orientation. However, how a respondent is asked to report their sexual orientation produces very different results: using the Kinsey Scale, 18% to 39% of Europeans and Americans identify as somewhere between heterosexual and homosexual, whereas only 0.5% to 1.9% of respondents identify as non-heterosexual when researchers force individuals to respond using only two categories. While the percentage of US adults identifying as LGBT (lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender) remains stable in older-aged cohorts, younger people are more likely to identify as LGBT than previous generations. Examples of terms currently used to identify sexual orientation include heterosexuality (attraction to the opposite sex/gender), homosexuality or same-sex attraction (attraction to the same sex/gender), bisexuality (attraction to two sexes/genders), polysexuality (attraction to multiple sexes/genders), pansexuality (attraction to all sexes/genders), and asexuality (no sexual attraction to any sex/gender).

References

Note: These references are specifically those added to the content of this page by Naomi Bahm and do not include citations from the outside sources used. Refer to the text attributions to locate citations for articles from other sources.

Bailey, J.M., Vasey, P.L., Diamond, L.M., Breedlove, S.M., Vilain, E., & Epprecht, M. (2016). Sexual orientation, controversy, and science. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 17(2), 45-101. doi: 10.1177/1529100616637616

Blanchard, R., Cantor, J., Bogaert, A., Breedlove, S.M., & Ellis, L. (2006). Interaction of fraternal birth order and handedness in the development of male homosexuality. Hormones and Behavior, 49, 405-414. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.09.002

Bogaert, A. (2007). Extreme right-handedness, older brothers, and sexual orientation in men. Neuropsychology, 21(1), 141-148. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.21.1.141

Dimock, M. (2019). Defining generations: Where Millennials end and Generation Z begins. Pew Research Center (January 17), https://pewrsr.ch/2szqtJz

Gates, G.J. (2017). LGBT data collection amid social and demographic shifts of the US LGBT community. American Journal of Public Health, 107 (8), 1220-1222. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.303927

O'Hanlan, K.A., Gordon, J.C., & Sullivan, M.W. (2018). Biological origins of sexual orientation and gender identity: Impact on health. Gynecologic Oncology, 149, 33-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.11.014

Additional Resources

Educational graphics for understanding sex, gender, sexual orientation, and more: https://www.itspronouncedmetrosexual.com/2018/10/the-genderbread-person-v4/

How do queer couples have babies? Learn more here:

Attributions

- Figures:

- First photo: Lesbian couple Sacramento by Bev Sykes from Davis, CA, USA, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons; Second photo: Two Men Midtown Baltimore MD by Elvert Barnes, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Own work (Kinsey Scale), licensed CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

- The four Marx Brothers by John Decker, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- A boy playing, nursing his doll by Ms. Melissa, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Text:

- The Psychology of Human Sexuality by Don Lucas and Jennifer Fox, licensed CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 via Noba Project.

- " Development of Sexual Identity" by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, LibreTexts is licensed under CC BY.

- Changes:

- Text from above two sources pieced together with some modifications, transitions and additional images and content (particularly in the sections A Continuum of Sexual Orientation, and Development and Origins of Sexual Orientation) added by Naomi I. Gribneau Bahm, PhD., Psychology Professor at Cosumnes River College, Sacramento, CA.

- Birth year ranges for Millennials and Baby Boomers from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tan...tion-z-begins/ (accessed 5/12/22; see Dimock, 2019 in references)