11: Sexual Orientation, Sexuality, and Pornography

- Page ID

- 55073

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

- Define terms related to sexuality and sexual expression.

- Discuss different theories and models for sexual orientation.

- Explain the impact of history on the LGBTQ population.

- Discuss current treatment concerns for the LGBTQ population.

- Explain the impact of socialization and culture on sexuality.

- Define the meaning of pornography.

-

Explore the disconnect between the consumption of pornography in the U.S. and public attitudes about pornography in the U.S.

- Discuss the impact of pornography replacing comprehensive sex education.

11.1 What is Sex, Gender, Sexuality, & Sexual Orientation?

Sex and Gender

Each of us is born with physical characteristics that represent and socially assign our sex and gender. Sex refers to our biological differences and gender the cultural traits assigned to females and males (Kottak and Kozaitis 2012). Our physical make-up distinguishes our sex as either female or male implicating the gender socialization process we will experience throughout our life associated with becoming a woman or man.

Gender identity is an individual’s self-concept of being female or male and their association with feminine and masculine qualities. People teach gender traits based on sex or biological composition (Kottak and Kozaitis 2012). Our sex signifies the gender roles (i.e., psychological, social, and cultural) we will learn and experience as a member of society. Children learn gender roles and acts of sexism in society through socialization (Griffiths et al. 2015). Girls learn feminine qualities and characteristics and boys masculine ones forming gender identity. Children become aware of gender roles between the ages of two and three and by four to five years old, they are fulfilling gender roles based on their sex (Griffiths et al. 2015). Nonetheless, gender-based characteristics do not always match one’s self or cultural identity as people grow and develop.

Gender stratification focuses on the unequal access females have to socially valued resources, power, prestige, and personal freedom as compared to men based on different positions within the socio-cultural hierarchy (Light, Keller, and Calhoun 1997). Traditionally, society treats women as second-class citizens in society. The design of dominant gender ideologies and inequality maintains the prevailing social structure, presenting male privilege as part of the natural order (Parenti 2006). Theorists suggest society is male-dominated patriarchy where men think of themselves as inherently superior to women resulting in an unequal distribution of rewards between men and women (Henslin 2011).

Media portrays women and men in stereotypical ways that reflect and sustain socially endorsed views of gender (Wood 1994). Media affects the perception of social norms including gender. People think and act according to stereotypes associated with one’s gender broadcast by media (Goodall 2016). Media stereotypes reinforce the gender inequality of girls and women. According to Wood (1994), the underrepresentation of women in media implies that men are the cultural standard, and women are unimportant or invisible. Stereotypes of men in media display them as independent, driven, skillful, and heroic lending them to higher-level positions and power in society.

In countries throughout the world, including the United States, women face discrimination in wages, occupational training, and job promotion (Parenti 2006). As a result, society tracks girls and women into career pathways that align with gender roles and match gender-linked aspirations such as teaching, nursing, and human services (Henslin 2011). Society views men’s work as having a higher value than that of women. Even if women have the same job as men, they make 77 cents per every dollar in comparison (Griffiths et al. 2015). Inequality in career pathways, job placement, and promotion or advancement results in an income gap between genders affecting the buying power and economic vitality of women in comparison to men.

The United Nations found prejudice and violence against women are firmly rooted in cultures around the world (Parenti 2006). Gender inequality has allowed men to harness and abuse their social power. The leading cause of injury among women of reproductive age is domestic violence, and rape is an everyday occurrence and seen as a male prerogative throughout many parts of the world (Parenti 2006). Depictions in the media emphasize male-dominant roles and normalize violence against women (Wood 1994). Culture plays an integral role in establishing and maintaining male dominance in society ascribing men the power and privilege that reinforces subordination and oppression of women.

Cross-cultural research shows gender stratification decreases when women and men make equal contributions to human subsistence or survival (Sanday 1974). Since the industrial revolution, attitudes about gender and work have been evolving with the need for women and men to contribute to the labor force and economy. Gendered work, attitudes, and beliefs have transformed in responses to American economic needs (Margolis 1984, 2000). Today’s society is encouraging gender flexibility resulting from cultural shifts among women seeking college degrees, prioritizing career, and delaying marriage and childbirth.

Sexuality and Sexual Orientation

Sexuality is an inborn person’s capacity for sexual feelings (Griffiths et al. 2015). Normative standards about sexuality are different throughout the world. Cultural codes prescribe sexual behaviors as legal, normal, deviant, or pathological (Kottak and Kozaitis 2012). In the United States, people have restrictive attitudes about premarital sex, extramarital sex, and homosexuality compared to other industrialized nations (Griffiths et al. 2015). The debate on

sex education in U.S. schools focuses on abstinence and contraceptive curricula. In addition, people in the U.S. have restrictive attitudes about women and sex, believing men have more urges and therefore it is more acceptable for them to have multiple sexual partners than women setting a double standard.

Sexual orientation is a biological expression of sexual desire or attraction (Kottak and Kozaitis 2012). Culture sets the parameters for sexual norms and habits. Enculturation dictates and controls social acceptance of sexual expression and activity. Eroticism like all human activities and preferences is learned and malleable (Kottak and Kozaitis 2012). Sexual orientation labels categorize personal views and representations of sexual desire and activities. Most people ascribe and conform to the sexual labels constructed and assigned by society (i.e., heterosexual or desire for the opposite sex, homosexual or attraction to the same sex, bisexual or appeal to both sexes, and asexual or lack of sexual attraction and indifference). The projection of one’s sexual personality is often through gender identity. Most people align their sexual disposition with what is socially or publically appropriate (Kottak and Kozaitis 2012). Because sexual desire or attraction is inborn, people within the socio-sexual dominant group (i.e., heterosexual) often believe their sexual preference is “normal.” However, heterosexual fit or type is not normal. History has documented diversity in sexual preference and behavior since the dawn of human existence (Kottak and Kozaitis 2012). There are diversity and variance in people’s libido and psychosocial relationship needs. Additionally, sexual activity or fantasy does not always align with sexual orientation (Kottak and Kozaitis 2012). Sexual pleasure from the use of sexual toys, homoerotic images, or kinky fetishes does not necessarily correspond to a specific orientation, sexual label, or mean someone’s desire will alter or convert to another type because of the activity. Regardless, society uses sexual identity as an indicator of status dismissing the fact that sexuality is a learned behavior, flexible, and contextual (Kottak and Kozaitis 2012). People feel and display sexual variety, erotic impulses, and sensual expressions throughout their lives.

Individuals develop sexual understanding around middle childhood and adolescence (APA 2008). There is no genetic, biological, developmental, social, or cultural evidence linked to homosexual behavior. The difference is in society’s discriminatory response to homosexuality. Alfred Kinsley was the first to identify sexuality is a continuum rather than a dichotomy of gay or straight (Griffiths et al. 2015). His research showed people do not necessarily fall into the sexual categories, behaviors, and orientations constructed by society. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick (1990) expanded on Kinsley’s research to find women are more likely to express homosocial relationships such as hugging, handholding, and physical closeness. Whereas, men often face negative sanctions for displaying homosocial behavior. Society ascribes meaning to sexual activities (Kottak and Kozaitis 2012). Variance reflects the cultural norms and sociopolitical conditions of a time and place. Since the 1970s, organized efforts by LGBTQ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning) activists have helped establish a gay culture and civil rights (Herdt 1992). Gay culture provides social acceptance for persons rejected, marginalized, and punished by others because of sexual orientation and expression. Queer theorists are reclaiming the derogatory label to help in broadening the understanding of sexuality as flexible and fluid (Griffiths et al. 2015). Sexual culture is not necessarily subject to sexual desire and activity, but rather dominant affinity groups linked by common interests or purpose to restrict and control sexual behavior.

11.2 Sexual Orientation and Inequality

Social Problems in the News

“Miami Beach to Fire Two Officers in Gay Beating at Park,” the headline said. City officials in Miami Beach, Florida, announced that the city would fire two police officers accused of beating a gay man two years earlier and kicking and arresting a gay tourist who came to the man’s defense. The tourist said he called 911 when he saw two officers, who were working undercover, beating the man and kicking his head. According to his account, the officers then shouted antigay slurs at him, kicked him, and arrested him on false charges. The president of Miami Beach Gay Pride welcomed the news of the impending firing. “It sets a precedent that you can’t discriminate against anyone and get away with it,” he said. “[The two officers] tried to cover it up and arrested the guy. It’s an abuse of power. Kudos to the city. They’ve taken it seriously.”

Source: Smiley & Rothaus, 2011

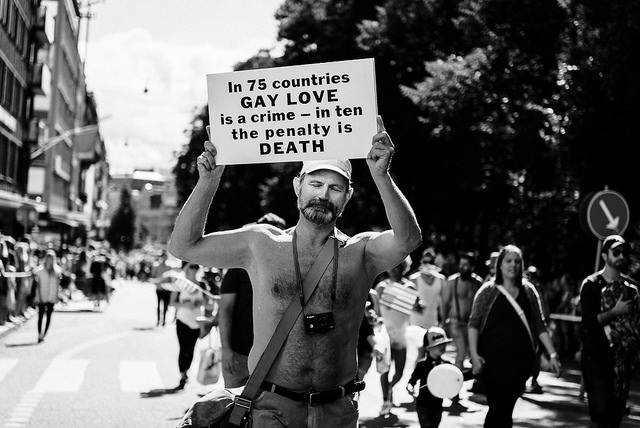

From 1933 to 1945, Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime exterminated 6 million Jews in the Holocaust, but it also persecuted millions of other people, including gay men. Nazi officials alleged that these men harbored what they termed a “degeneracy” that threatened Germany’s “disciplined masculinity.” Calling gay men “antisocial parasites” and “enemies of the state,” the Nazi government arrested more than 100,000 men for violating a law against homosexuality, although it did not arrest lesbians because it valued their child-bearing capacity. At least 5,000 gay men were imprisoned, and many more were put in mental institutions. Several hundred other gay men were castrated, and up to 15,000 were placed in concentration camps, where most died from disease, starvation, or murder. As the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (2011) summarizes these events, “Nazi Germany did not seek to kill all homosexuals. Nevertheless, the Nazi state, through active persecution, attempted to terrorize German homosexuals into sexual and social conformity, leaving thousands dead and shattering the lives of many more.”

This terrible history reminds us that sexual orientation has often resulted in inequality of many kinds, and, in the extreme case of the Nazis, the inhumane treatment that included castration, imprisonment, and death. The news story that began this chapter makes clear that sexual orientation still results in violence, even if this violence falls short of what the Nazis did. Although the gay rights movement has achieved much success, sexual orientation continues to result in other types of inequality as well. This chapter examines the many forms of inequality linked to sexual orientation today. It begins with a conceptual discussion of sexual orientation before turning to its history, explanation, types of inequality, and other matters.

References

Smiley, D. & Rothaus, S. (2011, July 25). Miami Beach to fire two officers in gay beating at park. The Miami Herald. Retrieved from http://miamiherald.typepad.com/gaysouthflorida/2011/07/miami-beach-to-fire-two-cops-who-beat-falsely-arrested-gay-man-at-flamingo-park.html.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (2011). Nazi persecution of homosexuals 1933–1945. Retrieved August 14, 2011, from http://www.ushmm.org/museum/exhibit/online/hsx/.

11.3 Understanding Sexual Orientation

Learning Objectives

- Define sexual orientation and gender identity.

- Describe what percentage of the U.S. population is estimated to be LGBT.

- Summarize the history of sexual orientation.

- Evaluate the possible reasons for sexual orientation.

Sexual orientation refers to a person’s preference for sexual relationships with individuals of the other sex (heterosexuality), one’s own sex (homosexuality), or both sexes (bisexuality). The term also increasingly refers to transgender (also transgendered) individuals, those whose behavior, appearance, and/or gender identity (the personal conception of oneself as female, male, both, or neither) departs from conventional norms. Transgendered individuals include transvestites (those who dress in the clothing of the opposite sex) and transsexuals (those whose gender identity differs from their physiological sex and who sometimes undergo a sex change). A transgender woman is a person who was born biologically as a male and becomes a woman, while a transgender man is a person who was born biologically as a woman and becomes a man. As you almost certainly know, gay is the common term now used for any homosexual individual; gay men or gays is the common term used for homosexual men, while lesbian is the common term used for homosexual women. All the types of social orientation just outlined are often collectively referred to by the shorthand LGBT (lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender). As you almost certainly also know, the term straight is used today as a synonym for heterosexual.

Counting Sexual Orientation

We will probably never know precisely how many people are gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgendered. One problem is conceptual. For example, what does it mean to be gay or lesbian? Does one need to actually have sexual relations with a same-sex partner to be considered gay? What if someone is attracted to same-sex partners but does not actually engage in sex with such persons? What if someone identifies as heterosexual but engages in homosexual sex for money (as in certain forms of prostitution) or for power and influence (as in much prison sex)? These conceptual problems make it difficult to determine the extent of homosexuality (Gates, 2011).

A second problem is empirical. Even if we can settle on a definition of homosexuality, how do we then determine how many people fit this definition? For better or worse, our best evidence of the number of gays and lesbians in the United States comes from surveys that ask random samples of Americans various questions about their sexuality. Although these are anonymous surveys, some individuals may be reluctant to disclose their sexual activity and thoughts to an interviewer. Still, scholars think that estimates from these surveys are fairly accurate but also that they probably underestimate by at least a small amount the number of gays and lesbians.

During the 1940s and 1950s, sex researcher Alfred C. Kinsey carried out the first notable attempt to estimate the number of gays and lesbians (Kinsey, Pomeroy, & Martin, 1948; Kinsey, Pomeroy, Martin, & Gebhard, 1953). His project interviewed more than 11,000 white women and men about their sexual experiences, thoughts, and attractions, with each subject answering hundreds of questions. While most individuals had experiences and feelings that were exclusively heterosexual, a significant number had experiences and feelings that were either exclusively homosexual or both heterosexual and homosexual in varying degrees. These findings led Kinsey to reject the popular idea back then that a person is necessarily either heterosexual or homosexual (or straight or gay, to use the common modern terms). As he wrote, “It is a characteristic of the human mind that tries to dichotomize in its classification of phenomena…Sexual behavior is either normal or abnormal, socially acceptable or unacceptable, heterosexual or homosexual; and many persons do not want to believe that there are gradations in these matters from one to the other extreme” (Kinsey et al., 1953, p. 469). Perhaps Kinsey’s most significant and controversial finding was that gradations did, in fact, exist between being exclusively heterosexual on the one hand and exclusively homosexual on the other hand. To reflect these gradations, he developed the well-known Kinsey Scale, which ranks individuals on a continuum ranging from 0 (exclusively heterosexual) to 6 (exclusively homosexual).

In terms of specific numbers, Kinsey found that (a) 37 percent of males and 13 percent of females had had at least one same-sex experience; (b) 10 percent of males had mostly homosexual experiences between the ages of 16 and 55, while up to 6 percent of females had mostly homosexual experiences between the ages of 20 and 35; (c) 4 percent of males were exclusively homosexual after adolescence began, compared to 1–3 percent of females; and (d) 46 percent of males either had engaged in both heterosexual and homosexual experiences or had been attracted to persons of both sexes, compared to 14 percent of females.

More recent research updates Kinsey’s early findings and, more importantly, uses nationally representative samples of Americans (which Kinsey did not use). In general, this research suggests that Kinsey overstated the numbers of Americans who have had same-sex experiences and/or attractions. A widely cited survey carried out in the early 1990s by researchers at the University of Chicago found that 2.8 percent of men and 1.4 percent of women self-identified as gay/lesbian or bisexual, with greater percentages reporting having had sexual relations with same-sex partners or being attracted to same-sex persons (see Table 5.1 “Prevalence of Homosexuality in the United States”). In the 2010 General Social Survey (GSS), 1.8 percent of men and 3.3 percent of women self-identified as gay/lesbian or bisexual. In the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) conducted by the federal government (Chandra, Mosher, Copen, & Sionean, 2011), 2.8 percent of men self-identified as gay or bisexual, compared to 4.6 percent of women (ages 18–44 for both sexes).

Table 5.1 Prevalence of Homosexuality in the United States

| Activity, attraction, or identity | Men (%) | Women (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Find same-sex sexual relations appealing | 4.5 | 5.6 |

| Attracted to people of same-sex | 6.2 | 4.4 |

| Identify as gay or bisexual | 2.8 | 1.4 |

| At least one sex partner of same-sex during the past year among those sexually active | 2.7 | 1.3 |

| At least one sex partner of same-sex since turning 18 | 4.9 | 4.1 |

Source: Data from Laumann, E. O., Gagnon, J. H., Michael, R. T., & Michaels, S. (1994). The social organization of sexuality. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

These are all a lot of numbers, but demographer Gary J. Gates (2011) drew on the most recent national survey evidence to come up with the following estimates for adults 18 and older:

- 3.5 percent of Americans identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual, and 0.3 percent are transgender; these figures add up to 3.8 percent of Americans, or 9 million people, who are LGBT.

- 3.4 percent of women and 3.6 percent of men identify as LGB.

- 66.7 percent of LGB women identify as bisexual, and 33.3 percent identify as a lesbian; 33.3 percent of LGB men identify as bisexual, and 66.7 percent identify as gay. LGB women are thus twice as likely as LGB men to identify as bisexual.

- 8.2 percent of Americans, or 19 million people, have engaged in same-sex sexual behavior, with women twice as likely as men to have done so.

- 11 percent of Americans, or 25.6 million people, report having some same-sex sexual attraction, with women twice as likely as men to report such attraction.

The overall picture from these estimates is clear: Self-identified LGBT people comprise only a small percentage of the US population, but they amount to about 9 million adults and undoubtedly a significant number of adolescents. In addition, the total number of people who, regardless of their sexual orientation, have had a same-sex experience is probably at least 19 million, and the number who have had same-sex attraction is probably at least 25 million.

Sexual Orientation in Historical Perspective

Based on what is known about homosexuality in past societies, it should be no surprise that so many people in the United States identify as gay/lesbian or have had same-sex experiences. This historical record is clear: Homosexuality has existed since ancient times and in some societies has been rather common or at least fully accepted as a normal form of sexual expression.

In the great city of Athens in ancient Greece, male homosexuality (to be more precise, sexual relations between a man and a teenaged boy and, less often, between a man and a man) was not only approved but even encouraged. According to classical scholar K. J. Dover (1989, p. 12), Athenian society “certainly regarded strong homosexual desire and emotion as normal,” in part because it also generally “entertained a low opinion of the intellectual capacity and staying-power of women.” Louis Crompton (2003, p. 2), who wrote perhaps the definitive history of homosexuality, agrees that male homosexuality in ancient Greece was common and notes that “in Greek history and literature…the abundance of accounts of homosexual love overwhelms the investigator.” He adds,

“Greek lyric poets sing of male love from almost the earliest fragments down to the end of classical times…Vase-painters portray scores of homoerotic scenes, hundreds of inscriptions celebrate the love of boys, and such affairs enter into the lives of a long catalog of famous Greek statesmen, warriors, artists, and authors. Though it has often been assumed that the love of males was a fashion confined to a small intellectual elite during the age of Plato, in fact, it was pervasive throughout all levels of Greek society and held an honored place in Greek culture for more than a thousand years, that is, from before 600 B.C.E. to about 400 C.E.”

Male homosexuality in ancient Rome was also common and accepted as normal sexuality, but it took a different form from than in ancient Greece. Ancient Romans disapproved of sexual relations between a man and a freeborn male youth, but they approved of relations between a slave master and his youthful male slave. Sexual activity of this type was common. As Crompton (2003, p. 80) wryly notes, “Opportunities were ample for Roman masters” because slaves comprised about 40 percent of the population of ancient Rome. However, these “opportunities” are best regarded as violent domination by slave masters over their slaves.

By the time Rome fell in 476 CE, Europe had become a Christian continent. Influenced by several passages in the Bible that condemn homosexuality, Europeans considered homosexuality a sin, and their governments outlawed same-sex relations. If discovered, male homosexuals (or any men suspected of homosexuality) were vulnerable to execution for the next fourteen centuries, and many did lose their lives. During the Middle Ages, gay men and lesbians were stoned, burned at the stake, hanged, or beheaded, and otherwise abused and mistreated. Crompton (2003, p. 539) calls these atrocities a “routine of terror” and a “kaleidoscope of horrors.” Hitler’s persecution of gay men several centuries after the Middle Ages ended had ample precedent in European history.

In contrast to the European treatment of gay men and lesbians, China and Japan from ancient times onward viewed homosexuality much more positively in what Crompton (2003, p. 215) calls an “unselfconscious acceptance of same-sex relations.” He adds that male love in Japan during the 1500s was “a national tradition—one the Japanese thought natural and meritorious” (Crompton, 2003, p. 412) and very much part of the samurai (military nobility) culture of preindustrial Japan. In China, both male and female homosexuality was seen as normal and even healthy sexual outlets. Because Confucianism, the major Chinese religion when the Common Era began, considered women inferior, it considered male friendships very important and thus may have unwittingly promoted same-sex relations among men. Various artistic and written records indicate that male homosexuality was fairly common in China over the centuries, although the exact numbers can never be known. When China began trading and otherwise communicating with Europe during the Ming dynasty, its tolerance for homosexuality shocked and disgusted Catholic missionaries and other Europeans. Some European clergy and scientists even blamed earthquakes and other natural disasters in China on this tolerance.

In addition to this body of work by historians, anthropologists have also studied same-sex relations in small, traditional societies. In many of these societies, homosexuality is both common and accepted as normal sexual behavior. In one overview of seventy-six societies, the authors found that almost two-thirds regarded homosexuality as “normal and socially acceptable for certain members of the community” (Ford & Beach, 1951, p. 130). Among the Azande of East Africa, for example, young warriors live with each other and are not allowed to marry. During this time, they often have sex with younger boys. Among the Sambia of New Guinea, young males live separately from females and have same-sex relations for at least a decade. It is felt that the boys would be less masculine if they continued to live with their mothers and that the semen of older males helps young boys become strong and fierce (Edgerton, 1976).

This brief historical and anthropological overview provides ready evidence of what was said at its outset: Homosexuality has existed since ancient times and in some societies has been rather common or at least fully accepted as a normal form of sexual expression. Although Western society, influenced by the Judeo-Christian tradition, has largely condemned homosexuality since Western civilization began some 2,000 years ago, the great civilizations of ancient Greece and ancient China and Japan until the industrial age approved of homosexuality. In these civilizations, male homosexuality was fairly common, and female homosexuality was far from unknown. Same-sex relations are also fairly common in many of the societies that anthropologists have studied. Although Western societies have long considered homosexuality sinful and unnatural and more generally have viewed it very negatively, the historical and anthropological record demonstrates that same-sex relationships are far from rare. They thus must objectively be regarded as normal expressions of sexuality.

In fact, some of the most famous individuals in Western political, literary, and artistic history certainly or probably engaged in same-sex relations, either sometimes or exclusively: Alexander the Great, Hans Christian Andersen, Marie Antoinette, Aristotle, Sir Francis Bacon, James Baldwin, Leonard Bernstein, Lord Byron, Julius Caesar, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Frederick the Great, Leonardo de Vinci, Herman Melville, Michelangelo, Plato, Cole Porter, Richard the Lionhearted, Eleanor Roosevelt, Socrates, Gertrude Stein, Pyotr Tchaikovsky, Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, Tennessee Williams, Oscar Wilde, and Virginia Woolf, to name just a few. Regardless or perhaps in some cases because of their sexuality, they all made great contributions to the societies in which they lived.

Explaining Sexual Orientation

We have seen that it is difficult to determine the number of people who are gay/lesbian or bisexual. It is even more difficult to determine why some people have these sexual orientations while most do not, and scholars disagree on the “causes” of sexual orientation (Engle, McFalls, Gallagher, & Curtis, 2006; Sheldon, Pfeffer, Jayaratne, Feldbaum, & Petty, 2007). Determining the origins of sexual orientation is not just an academic exercise. When people believe that the roots of homosexuality are biological or that gays otherwise do not choose to be gay, they are more likely to have positive or at least tolerant views of same-sex behavior. When they believe that homosexuality is instead merely a personal choice, they are more likely to disapprove of it (Sheldon et al., 2007). For this reason, if for no other, it is important to know why some people are gay or bisexual while most are not.

Studies of the origins of sexual orientation focus mostly on biological factors and on social and cultural factors, and a healthy scholarly debate exists on the relative importance of these two sets of factors.

Biological Factors

Research points to certain genetic and other biological roots of sexual orientation but is by no means conclusive. One line of research concerns genetics. Although no “gay gene” has been discovered, studies of identical twins find they are more likely to have the same sexual orientation (gay or straight) than would be expected from chance alone (Kendler, Thornton, Gilman, & Kessler, 2000; Santtila et al., 2008). Because identical twins have the same DNA, this similarity suggests but does not prove, a genetic basis for sexual orientation. Keep in mind, however, that any physical or behavioral trait that is totally due to genetics should show up in both twins or in neither twin. Because many identical twins do not have the same sexual orientation, this dissimilarity suggests that genetics are far from the only cause of sexual orientation, to the extent they cause it at all. Several methodological problems also cast doubt on findings from many of these twin studies. A recent review concluded that the case for a genetic cause of sexual orientation is far from proven: “Findings from genetic studies of homosexuality in humans have been confusing—contradictory at worst and tantalizing at best—with no clear, strong, compelling

Another line of research concerns brain anatomy, as some studies find differences in the size and structure of the hypothalamus, which controls many bodily functions, in the brains of gays versus the brains of straights (Allen & Gorski, 1992). However, other studies find no such differences (Lasco, Jordan, Edgar, Petito, & Byne, 2002). Complicating matters further, because sexual behavior can affect the hypothalamus (Breedlove, 1997), it is difficult to determine whether any differences that might be found reflect the influence of the hypothalamus on sexual orientation, or instead of the influence of sexual orientation on the hypothalamus (Sheldon et al., 2007).

The third line of biological research concerns hormonal balance in the womb, with scientists speculating that the level of prenatal androgen effects in which sexual orientation develops. Because prenatal androgen levels cannot be measured, studies typically measure it only indirectly in the bodies of gays and straights by comparing the lengths of certain fingers and bones that are thought to be related to prenatal androgen. Some of these studies suggest that gay men had lower levels of prenatal androgen than straight men and that lesbians had higher levels of prenatal androgen than straight women, but other studies find no evidence of this connection (Martin & Nguyen, 2004; Mustanski, Chivers, & Bailey, 2002). A recent review concluded that the results of the hormone studies are “often inconsistent” and that “the notion that non-heterosexual preferences may reflect [deviations from normal prenatal hormonal levels] is not supported by the available data” (Rahman, 2005, p. 1057).

Social and Cultural Factors

Sociologists usually emphasize the importance of socialization over biology for the learning of many forms of human behavior. In this view, humans are born with “blank slates” and thereafter shaped by their society and culture, and children are shaped by their parents, teachers, peers, and other aspects of their immediate social environment while they are growing up.

Given this standard sociological position, one might think that sociologists generally believe that people are gay or straight not because of their biology but because they learn to be gay or straight from their society, culture, and immediate social environment. This, in fact, was a common belief of sociologists about a generation ago (Engle et al., 2006). In a 1988 review article, two sociologists concluded that “evidence that homosexuality is a social construction [learned from society and culture] is far more powerful than the evidence for a widespread organic [biological] predisposition toward homosexual desire” (Risman & Schwartz, 1988, p. 143). The most popular introductory sociology text of the era similarly declared, “Many people, including some homosexuals, believe that gays and lesbians are simply ‘born that way.’ But since we know that even heterosexuals are not ‘born that way,’ this explanation seems unlikely…Homosexuality, like any other sexual behavior ranging from oral sex to sadomasochism to the pursuit of brunettes, is learned” (Robertson, 1987, p. 243).

However, sociologists’ views of the origins of sexual orientation have apparently changed since these passages were written. In a recent national survey of a random sample of sociologists, 22 percent said male homosexuality results from biological factors, 38 percent said it results from both biological and environmental (learning) factors, and 39 percent said it results from environmental factors (Engle et al., 2006). Thus 60 percent (= 22 + 38) thought that biology totally or partly explains male homosexuality, almost certainly a much higher figure than would have been found a generation ago had a similar survey been done.

In this regard, it is important to note that 77 percent (= 38 + 39) of the sociologists still feel that environmental factors, or socialization, matter as well. Scholars who hold this view believe that sexual orientation is partly or totally learned from one’s society, culture, and immediate social environment. In this way of thinking, we learn “messages” from all these influences about whether it is OK or not OK to be sexually attracted to someone from our own sex and/or to someone from the opposite sex. If we grow up with positive messages about same-sex attraction, we are more likely to acquire this attraction. If we grow up with negative messages about same-sex attraction, we are less likely to acquire it and more likely to have a heterosexual desire.

It is difficult to do the necessary type of research to test whether socialization matters in this way, but the historical and cross-cultural evidence discussed earlier provides at least some support for this process. Homosexuality was generally accepted in ancient Greece, ancient China, and ancient Japan, and it also seemed rather common in those societies. The same connection holds true in many of the societies that anthropologists have studied. In contrast, homosexuality was condemned in Europe from the very early part of the first millennium CE, and it seems to have been rather rare (although it is very possible that many gays hid their sexual orientation for fear of persecution and death).

So where does this leave us? What are the origins of sexual orientation? The most honest answer is that we do not yet know its origins. As we have seen, many scholars attribute sexual orientation to still unknown biological factor(s) over which individuals have no control, just as individuals do not decide whether they are left-handed or right-handed. Supporting this view, many gays say they realized they were gay during adolescence, just as straights would say they realized they were straight during their own adolescence; moreover, evidence (from toy, play, and clothing preferences) of future sexual orientation even appears during childhood (Rieger, Linsenmeier, Bailey, & Gygax, 2008). Other scholars say that sexual orientation is at least partly influenced by cultural norms so that individuals are more likely to identify as gay or straight and be attracted to their same-sex or opposite-sex depending on the cultural views of sexual orientation into which they are socialized as they grow up. At best, perhaps all we can say is that sexual orientation stems from a complex mix of biological and cultural factors that remain to be determined.

The official stance of the American Psychological Association (APA) is in line with this view. According to the APA, “There is no consensus among scientists about the exact reasons that an individual develops a heterosexual, bisexual, gay, or lesbian orientation. Although much research has examined the possible genetic, hormonal, developmental, social, and cultural influences on sexual orientation, no findings have emerged that permit scientists to conclude that sexual orientation is determined by any particular factor or factors. Many think that nature and nurture both play complex roles; most people experience little or no sense of choice about their sexual orientation” (American Psychological Association, 2008, p. 2).

Although the exact origins of sexual orientation remain unknown, the APA’s last statement is perhaps the most important conclusion from research on this issue: Most people experience little or no sense of choice about their sexual orientation. Because, as mentioned earlier, people are more likely to approve of or tolerate homosexuality when they believe it is not a choice, efforts to educate the public about this research conclusion should help the public become more accepting of LGBT behavior and individuals.

Key Takeaways

- An estimated 3.8 percent, or 9 million, Americans identify as LGBT.

- Homosexuality seems to have been fairly common and very much accepted in some ancient societies as well as in many societies studied by anthropologists.

- Scholars continue to debate the extent to which sexual orientation stems more from biological factors or from social and cultural factors and the extent to which sexual orientation is a choice or not a choice.

For Your Review

- Do you think sexual orientation is a choice, or not? Explain your answer.

- Write an essay that describes how your middle school and high school friends talked about sexual orientation generally and homosexuality specifically.

References

Allen, L. S., & Gorski, R. A. (1992). Sexual orientation and the size of the anterior commissure in the human brain. PNAS, 89, 7199–7202.

American Psychological Association. (2008). Answers to your questions: For a better understanding of sexual orientation and homosexuality. Washington, DC: Author.

Breedlove, M. S. (1997). Sex on the brain. Nature, 389, 801.

Chandra, A., Mosher, W. D., Copen, C., & Sionean, C. (2011). Sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and sexual identity in the United States: Data from the 2006–2008 national survey of family growth (National Health Statistics Reports: Number 36). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr036.pdf.

Crompton, L. (2003). Homosexuality and civilization. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Dover, K. J. (1989). Greek homosexuality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Edgerton, R. (1976). Deviance: A cross-cultural perspective. Menlo Park, CA: Cummings Publishing.

Engle, M. J., McFalls, J. A., Jr., Gallagher, B. J., III, & Curtis, K. (2006). The attitudes of American sociologists toward causal theories of male homosexuality. The American Sociologist, 37(1), 68–76.

Ford, C. S., & Beach, F. A. (1951). Patterns of sexual behavior. New York: Harper and Row.

Gates, G. J. (2011). How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender? Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute.

Kendler, K. S., Thornton, L. M., Gilman, S. E., & Kessler, R. C. (2000). Sexual orientation in a US national sample of twin and nontwin sibling pairs. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 1843–1846.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual behavior in the human male. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., Martin, C. E., & Gebhard, P. H. (1953). Sexual behavior in the human female. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders.

Lasco, M. A., Jordan, T. J., Edgar, M. A., Petito, C. K., & Byne, W. (2002). A lack of dimporphism of sex or sexual orientation in the human anterior commissure. Brain Research, 986, 95–98.

Martin, J. T., & Nguyen, D. H. (2004). Anthropometric analysis of homosexuals and heterosexuals: Implications for early hormone exposure. Hormones and Behavior, 45, 31–39.

Mustanski, B. S., Chivers, M. L., & Bailey, J. M. (2002). A critical review of recent biological research on human sexual orientation. Annual Review of Sex Research, 13, 89–140.

Rahman, Q. (2005). The neurodevelopment of human sexual orientation. Neuroscience Biobehavioral Review, 29(7), 1057–1066.

Rieger, G., Linsenmeier, J. A. W., Bailey, J. M., & Gygax, L. (2008). Sexual orientation and childhood gender nonconformity: Evidence from home videos. Developmental Psychology, 44(1), 46–58.

Risman, B., & Schwartz, P. (1988). Sociological research on male and female homosexuality. Annual Review of Sociology, 14, 125–147.

Robertson, I. (1987). Sociology. New York, NY: Worth.

Santtila, P., Sandnabba, N. K., Harlaar, N., Varjonen, M., Alanko, K., & Pahlen, B. v. d. (2008). Potential for homosexual response is prevalent and genetic. Biological Psychology, 77, 102–105.

Sheldon, J. P., Pfeffer, C. A., Jayaratne, T. E., Feldbaum, M., & Petty, E. M. (2007). Beliefs about the etiology of homosexuality and about the ramifications of discovering its possible genetic origin. Journal of Homosexuality, 52(3/4), 111–150.

11.4 Public Attitudes About Sexual Orientation

Learning Objectives

- Understand the extent and correlates of heterosexism.

- Understand the nature of public opinion on other issues related to sexual orientation.

- Describe how views about LGBT issues have changed since a few decades ago.

As noted earlier, views about gays and lesbians have certainly been very negative over the centuries in the areas of the world, such as Europe and the Americas, that mostly follow the Judeo-Christian tradition. There is no question that the Bible condemns homosexuality, with perhaps the most quoted Biblical passages in this regard found in Leviticus:

- “Do not lie with a man as one lies with a woman; that is detestable” (Leviticus 18:22).

- “If a man lies with a man as one lies with a woman, both of them have done what is detestable. They must be put to death; their blood will be on their own heads” (Leviticus 20:13).

The important question, though, is to what extent these passages should be interpreted literally. Certainly very few people today believe that male homosexuals should be executed, despite what Leviticus 20:13 declares. Still, many people who condemn homosexuality cite passages like Leviticus 18:22 and Leviticus 20:13 as reasons for their negative views.

This is not a theology text, but it is appropriate to mention briefly two points that many religious scholars make about what the Bible says about homosexuality (Helminiak, 2000; Via & Gagnon, 2003). First, English translations of the Bible’s antigay passages may distort their original meanings, and various contextual studies of the Bible suggest that these passages did not, in fact, make blanket condemnations about homosexuality.

Second, and perhaps more important, most people “pick and choose” what they decide to believe from the Bible and what they decide not to believe. Although the Bible is a great source of inspiration for many people, most individuals are inconsistent when it comes to choosing which Biblical beliefs to believe and about which beliefs not to believe. For example, if someone chooses to disapprove of homosexuality because the Bible condemns it, why does this person not also choose to believe that gay men should be executed, which is precisely what Leviticus 20:13 dictates? Further, the Bible calls for many practices and specifies many penalties that even very devout people do not follow or believe. For example, most people except for devout Jews do not keep kosher, even though the Bible says that everyone should do this, and most people certainly do not believe people who commit adultery, engage in premarital sex or work on the Sabbath should be executed, even though the Bible says that such people should be executed. Citing the inconsistency with which most people follow Biblical commands, many religious scholars say it is inappropriate to base public views about homosexuality on what the Bible says about it.

We now turn our attention to social science evidence on views about LGBT behavior and individuals. We first look at negative attitudes and then discuss a few other views.

The Extent of Heterosexism in the United States

We saw in earlier chapters that racism refers to negative views about, and practices toward, people of color, and that sexism refers to negative views about, and practices toward, women. Heterosexism is the analogous term for negative views about, and discriminatory practices toward, LGBT individuals and their sexual behavior.

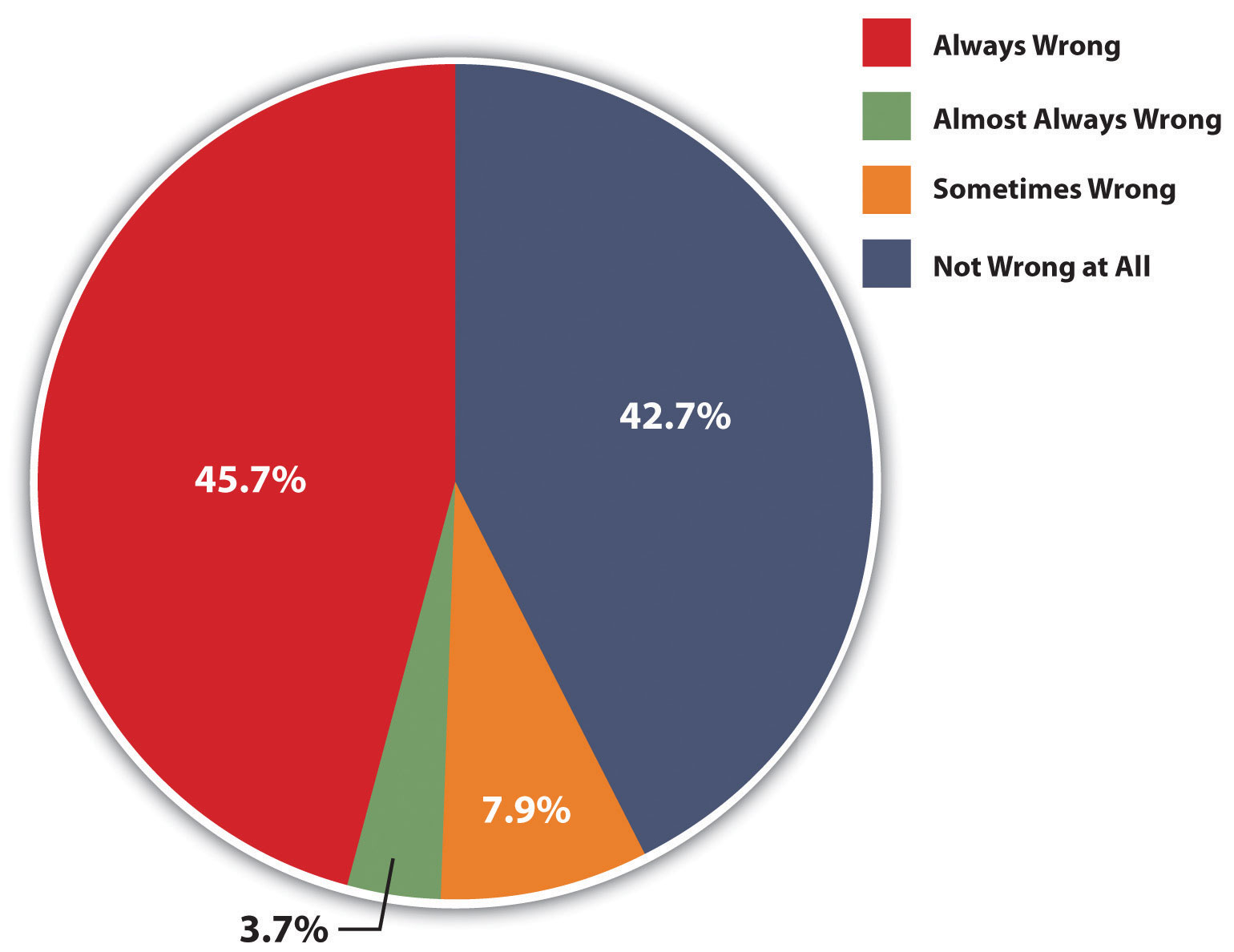

There are many types of negative views about LGBT and thus many ways to measure heterosexism. The General Social Survey (GSS), given regularly to a national sample of US residents, asks whether respondents think that “sexual relations between two adults of the same sex” are always wrong, almost always wrong, sometimes wrong, or not wrong at all. In 2010, almost 46 percent of respondents said same-sex relations are “always wrong,” and 43 percent responded they are “not wrong at all” (see Figure 5.1 “Opinion about “Sexual Relations between Two Adults of the Same Sex,” 2010”).

Figure 5.1 Opinion about “Sexual Relations between Two Adults of the Same Sex,” 2010

As another way of measuring heterosexism, the Gallup poll asks whether “gay or lesbian relations” are “morally acceptable or morally wrong” (Gallup, 2011). In 2011, 56 percent of Gallup respondents answered “morally acceptable,” while 39 percent replied “morally wrong.”

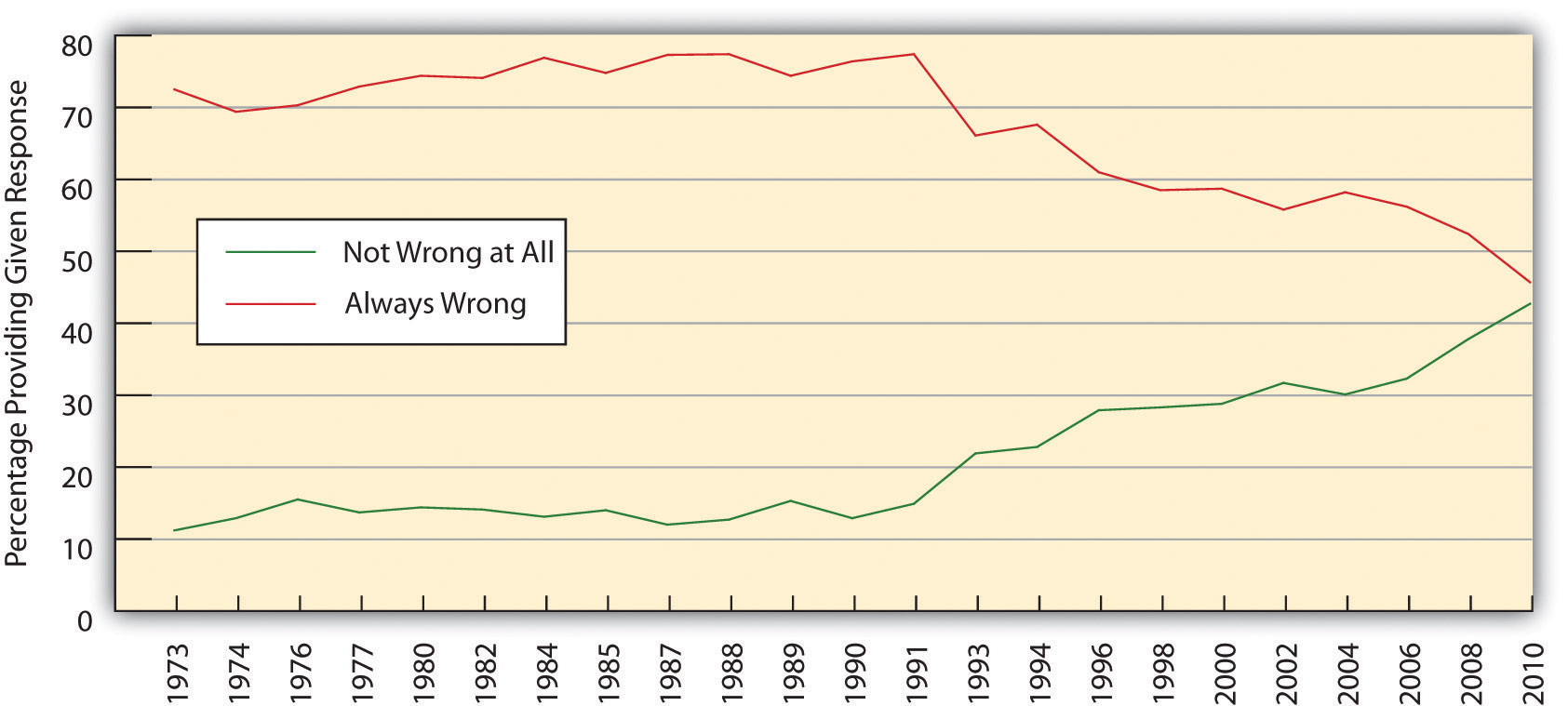

Although Figure 5.1 “Opinion about “Sexual Relations between Two Adults of the Same Sex,” 2010” shows that 57.3 percent of Americans (= 45.7 + 3.7 + 7.9) think that same-sex relations are at least sometimes wrong, public views regarding LGBT have notably become more positive over the past few decades. We can see evidence of this trend in Figure 5.2 “Changes in Opinion about “Sexual Relations between Two Adults of the Same Sex,” 1973–2010”, which shows that the percentage of GSS respondents who say same-sex relations are “always wrong” has dropped considerably since the GSS first asked this question in 1973, while the percentage who respond “not wrong at all” has risen considerably, with both these changes occurring since the early 1990s.

Figure 5.2 Changes in Opinion about “Sexual Relations between Two Adults of the Same Sex,” 1973–2010

Trends in Gallup data confirm that public views regarding homosexuality have become more positive in recent times. Recall that 56 percent of Gallup respondents in 2011 called same-sex relations “morally acceptable,” while 39 percent replied “morally wrong.” Ten years earlier, these percentages were 40 percent and 53 percent, respectively, representing a marked shift in public opinion in just a decade.

Correlates of Heterosexism

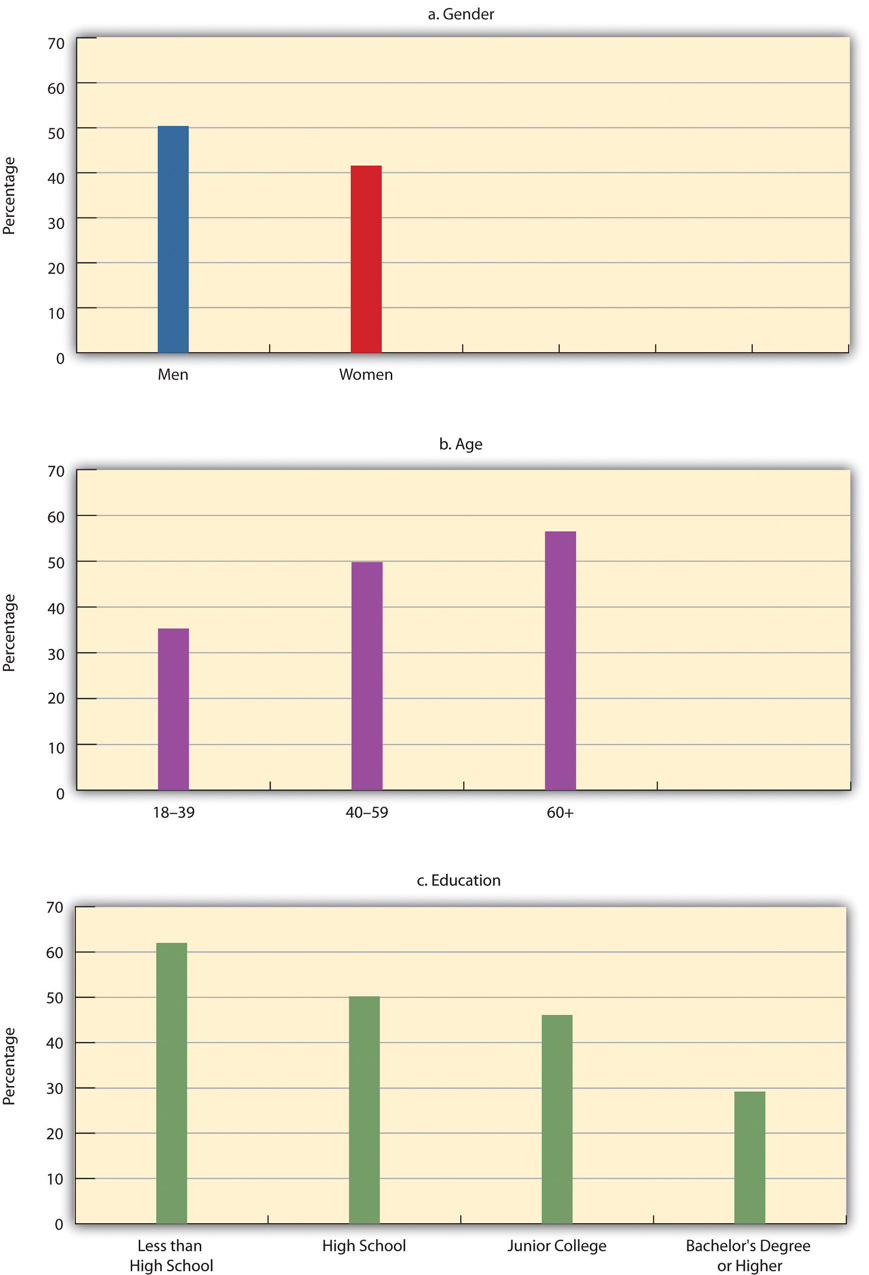

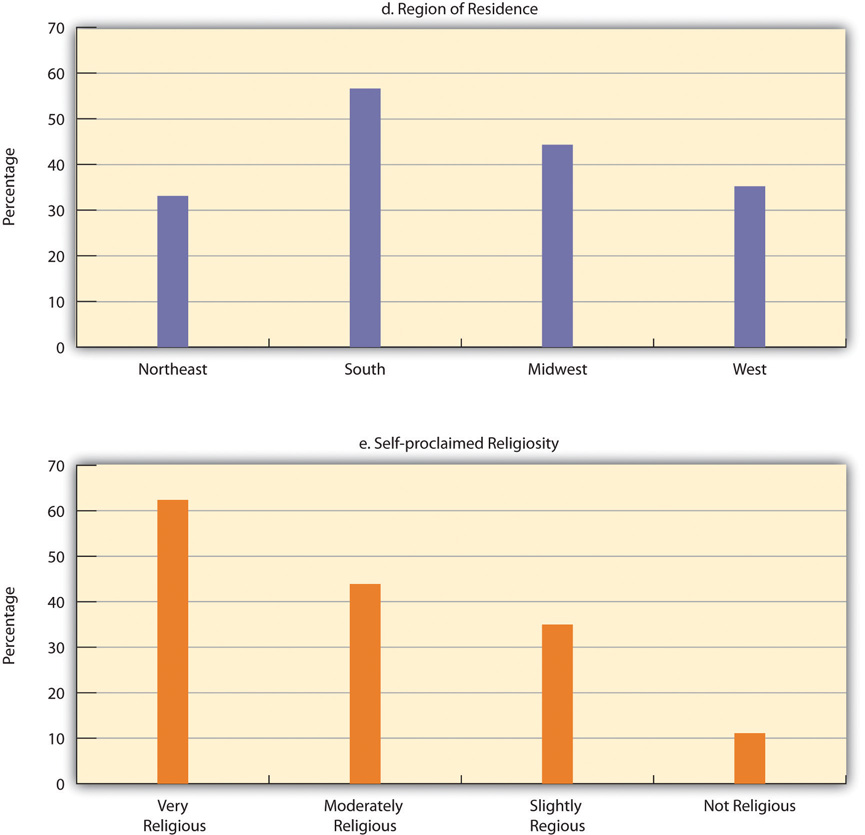

Scholars have investigated the sociodemographic factors that predict heterosexist attitudes. Reflecting on the sociological axiom that our social backgrounds influence our attitudes and behavior, several aspects of our social backgrounds influence views about gays and lesbians. Among the most influential of these factors are gender, age, education, the region of residence, and religion. We can illustrate each of these influences with the GSS question on whether same-sex relations are wrong, using the response “always wrong” as a measure of heterosexism.

- Gender. Men are somewhat more heterosexist than women (see part a of Figure 5.3 “Correlates of Heterosexism (Percentage Saying That Same-Sex Relations Are “Always Wrong”)”).

- Age. Older people are considerably more heterosexist than younger people (see part b of Figure 5.3 “Correlates of Heterosexism (Percentage Saying That Same-Sex Relations Are “Always Wrong”)”).

- Education. Less educated people are considerably more heterosexist than more educated people (see part c of Figure 5.3 “Correlates of Heterosexism (Percentage Saying That Same-Sex Relations Are “Always Wrong”)”).

- Region of residence. Southerners are more heterosexist than non-Southerners (see part d of Figure 5.3 “Correlates of Heterosexism (Percentage Saying That Same-Sex Relations Are “Always Wrong”)”).

- Religion. Religious people are considerably more heterosexist than less religious people (see part e of Figure 5.3 “Correlates of Heterosexism (Percentage Saying That Same-Sex Relations Are “Always Wrong”)”).

Figure 5.3 Correlates of Heterosexism (Percentage Saying That Same-Sex Relations Are “Always Wrong”)

The age difference in heterosexism is perhaps particularly interesting. Many studies find that young people—those younger than 30—are especially accepting of homosexuality and of same-sex marriage. As older people, who have more negative views, pass away, it is likely that public opinion as a whole will become more accepting of homosexuality and issues related to it. Scholars think this trend will further the legalization of same-sex marriage and the establishment of other laws and policies that will reduce the discrimination and inequality that the LGBT community experiences (Gelman, Lax, & Phillips, 2010).

Opinion on the Origins of Sexual Orientation

Earlier we discussed scholarly research on the origins of sexual orientation. In this regard, it is interesting to note that the US public is rather split over the issue of whether sexual orientation is in-born instead the result of environmental factors, and also over the closely related issue of whether it is something people are able to choose. A 2011 Gallup poll asked, “In your view, is being gay or lesbian something a person is born with, or due to factors such as upbringing and environment?” (Jones, 2011). Forty percent of respondents replied that sexual orientation is in-born, while 42 percent said it stems from upbringing and/or environment. The 40 percent in-born figure represented a sharp increase from the 13 percent figure that Gallup obtained when it first asked this question in 1977. A 2010 CBS News poll, asked, “Do you think being homosexual is something people choose to be, or do you think it is something they cannot change?” (CBS News, 2010). About 36 percent of respondents replied that homosexuality is a choice, while 51 percent said it is something that cannot be changed, with the remainder saying they did not know or providing no answer. The 51 percent “cannot change” figure represented an increase from the 43 percent figure that CBS News obtained when it first asked this question in 1993.

Other Views

The next section discusses several issues that demonstrate inequality based on sexual orientation. Because these issues are so controversial, public opinion polls have included many questions about them. We examine public views on some of these issues in this section.

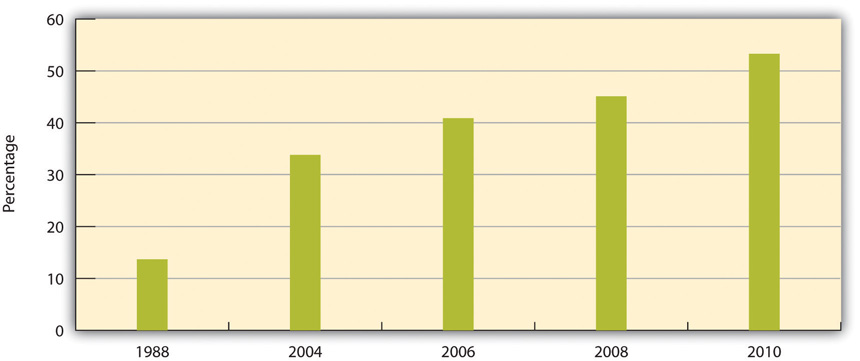

A first issue is same-sex marriage. The 2010 GSS asked whether respondents agree that “homosexual couples should have the right to marry one another”: 53.3 percent of respondents who expressed an opinion agreed with this statement, and 46.7 percent disagreed, indicating a slight majority in favor of legalizing same-sex marriage (SDA, 2010). In 2011, an ABC News/Washington Post poll asked about same-sex marriage in a slightly different way: “Do you think it should be legal or illegal for gay and lesbian couples to get married?” A majority, 51 percent, of respondents, replied “legal,” and 45 percent replied, “illegal” (Langer, 2011). Although only bare majorities now favor legalizing same-sex marriage, public views on this issue have become much more positive in recent years. We can see dramatic evidence of this trend in Figure 5.4 “Changes in Opinion about Same-Sex Marriage, 1988–2010 (Percentage Agreeing That Same-Sex Couples Should Have the Right to Marry; Those Expressing No Opinion Excluded from Analysis)”, which shows that the percentage agreeing with the GSS question on the right of same-sex couples to marry has risen considerably during the past quarter-century.

Figure 5.4 Changes in Opinion about Same-Sex Marriage, 1988–2010 (Percentage Agreeing That Same-Sex Couples Should Have the Right to Marry; Those Expressing No Opinion Excluded from Analysis)

In a related topic, public opinion about same-sex couples as parents has also become more favorable in recent years. In 2007, 50 percent of the public said that the increasing number of same-sex couples raising children was “a bad thing” for society. By 2011, this figure had declined to 35 percent, a remarkable decrease in just four years (Pew Research Center, 2011).

A second LGBT issue that has aroused public debate involves the right of gays and lesbians to serve in the military, which we discuss further later in this chapter. A 2010 ABC News/Washington Post poll asked whether “gays and lesbians who do not publicly disclose their sexual orientation should be allowed to serve in the military” (Mokrzycki, 2010). About 83 percent of respondents replied they “should be allowed,” up considerably from the 63 percent figure that this poll obtained when it first asked this question in 1993 (Saad, 2008).

A third issue involves the right of gays and lesbians to be free from job discrimination based on their sexual orientation, as federal law does not prohibit such discrimination. A 2008 Gallup poll asked whether “homosexuals should or should not have equal rights in terms of job opportunities.” About 89 percent of respondents replied that there “should be” such rights, and only 8 percent said there “should not be” such rights. The 89 percent figure represented a large increase from the 56 percent figure that Gallup obtained in 1977 when Gallup first asked this question.

Two Brief Conclusions on Public Attitudes

We have had limited space to discuss public views on LGBT topics, but two brief conclusions are apparent from the discussion. First, although the public remains sharply divided on various LGBT issues and much of the public remains heterosexist, views about LGBT behavior and certain rights of the LGBT community have become markedly more positive in recent decades. This trend matches what we saw in earlier chapters regarding views concerning people of color and women. The United States has without question become less racist, less sexist, and less heterosexist since the 1970s.

Second, certain aspects of people’s sociodemographic backgrounds influence the extent to which they do, or do not, hold heterosexist attitudes. This conclusion is not surprising, as sociology has long since demonstrated that social backgrounds influence many types of attitudes and behaviors, but the influence we saw earlier of sociodemographic factors on heterosexism was striking nonetheless. These factors would no doubt also be relevant for understanding differences in views on other LGBT issues. As you think about your own views, perhaps you can recognize why you might hold these views based on your gender, age, education, and other aspects of your social background.

Key Takeaways

- Views about LGBT behavior have improved markedly since a generation ago. More than half the US public now supports same-sex marriage.

- Males, older people, the less educated, Southerners, and the more religious exhibit higher levels of heterosexism than their counterparts.

For Your Review

-

Reread this section and indicate how you would have responded to every survey question discussed in the section. Drawing on the discussion of correlates of heterosexism, explain how knowing about these correlates helps you understand why you hold your own views.

-

Why do you think public opinion about LGBT behavior and issues has become more positive during the past few decades?

References

CBS News. (2010, June 9). CBS News poll: Views of gays and lesbians. Retrieved from http://www.cbsnews.com/htdocs/pdf/poll_gays_lesbians_060910.pdf.

Gallup. (2011). Gay and lesbian rights. Gallup. Retrieved September 4, 2011, from http://www.gallup.com/poll/1651/gay-lesbian-rights.aspx.

Gelman, A., Lax, J., & Phillips, J. (2010, August 22). Over time, a gay marriage groundswell. New York Times, p. WK3.

Helminiak, D. A. (2000). What the Bible really says about homosexuality. Tajique, NM: Alamo Square Press.

Jones, Jeffrey M. (2011). Support for legal gay relations hits new high. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/147785/Support-Legal-Gay-Relations-Hits-New-High.aspx.

Langer, Gary. (2011). Support for gay marriage reaches a milestone. Retrieved from http://abcnews.go.com/Politics/support-gay-marriage-reaches-milestone-half-americans-support/story?id=13159608#.T66_kp9YtQp.

Mokrzycki, Mike. (2010). Support for gays in the military crosses ideological, party lines. Retrieved from http://abcnews.go.com/PollingUnit/poll-support-gays-military-crosses-ideological-party-lines/story?id=9811516#.T67A659YtQo.

Pew Research Center. (2011). 35%—Disapprove of gay and lesbian couples raising children. Retrieved from http://pewresearch.org/databank/dailynumber/?NumberID=1253.

Saad, Lydia. (2008). Americans evenly divided on morality of homosexuality. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/108115/americans-evenly-divided-morality-homosexuality.aspx.

SDA. (2010). GSS 1972–2010 cumulative datafile. Retrieved from http://sda.berkeley.edu/cgi-bin/hsda?harcsda+gss10.

Via, D. O., & Gagnon, R. A. J. (2003). Homosexuality and the Bible: Two views. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press.

11.5 Inequality Based on Sexual Orientation

Learning Objectives

- Understand the behavioral, psychological, and health effects of bullying and other mistreatment of the LGBT community.

- Evaluate the arguments for and against same-sex marriage.

- Provide three examples of heterosexual privilege.

Until just a decade ago, individuals who engaged in consensual same-sex relations could be arrested in many states for violating so-called sodomy laws. The US Supreme Court, which had upheld such laws in 1986, finally outlawed them in 2003 in Lawrence v. Texas, 539 US 558, by a 6–3 vote. The majority opinion of the court declared that individuals have a constitutional right under the Fourteenth Amendment to engage in consensual, private sexual activity.

Despite this landmark ruling, the LGBT community continues to experience many types of problems. In this regard, sexual orientation is a significant source of social inequality, just as race/ethnicity, gender, and social class are sources of social inequality. We examine manifestations of inequality based on sexual orientation in this section.

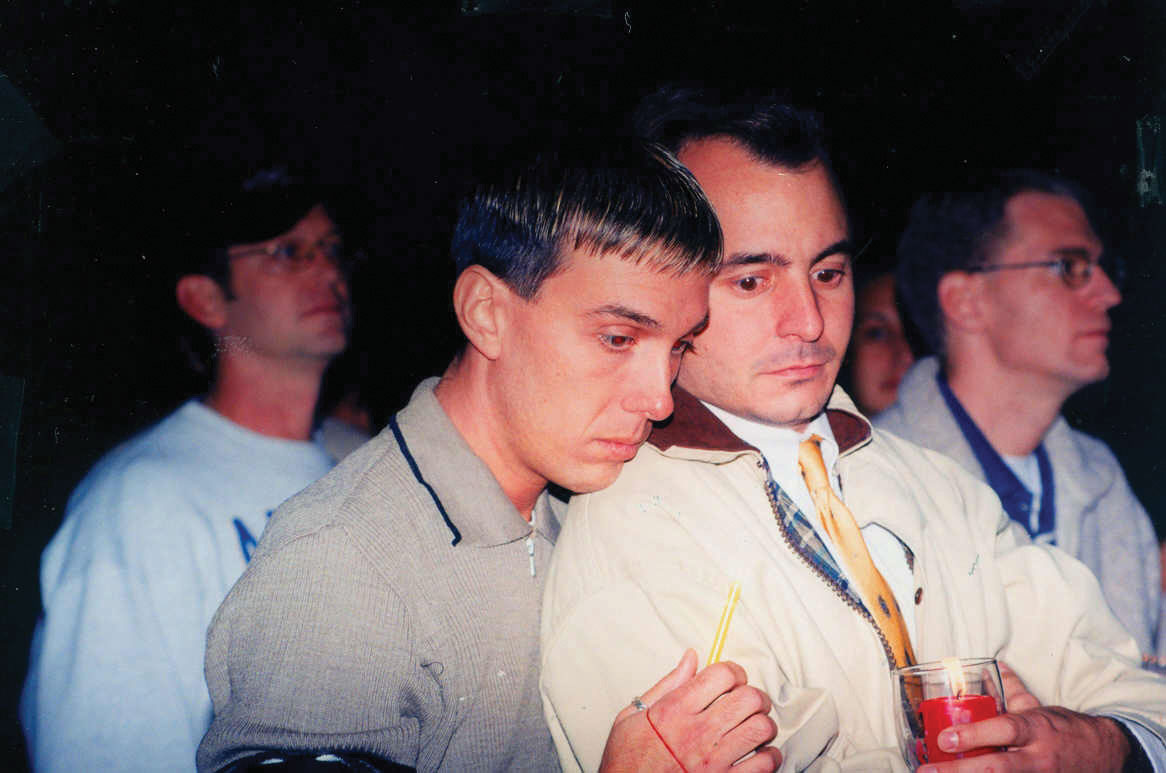

Bullying and Violence

The news story that began this chapter concerned the reported beatings of two gay men. Bullying and violence against adolescents and adults thought or known to be gay or lesbian constitute perhaps the most serious manifestation of inequality based on sexual orientation. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (2011), 1,277 hate crimes (violence and/or property destruction) against gays and lesbians occurred in 2010, although this number is very likely an underestimate because many hate crime victims do not report their victimization to the police. An estimated 25 percent of gay men have been physically or sexually assaulted because of their sexual orientation (Egan, 2010), and some have been murdered. Matthew Shepard was one of these victims. He was a student at the University of Wyoming in October 1998 when he was kidnapped by two young men who tortured him, tied him to a fence, and left him to die. When finding out almost a day later, he was in a coma, and he died a few days later. Shepard’s murder prompted headlines around the country and is credited with winning public sympathy for the problems experienced by the LGBT community (Loffreda, 2001).

Gay teenagers and straight teenagers thought to be gay are very often the targets of taunting, bullying, physical assault, and other abuse in schools and elsewhere (Denizet-Lewis, 2009). Survey evidence indicates that 85 percent of LGBT students report being verbally harassed at school, and 40 percent report being verbally harassed; 72 percent report hearing antigay slurs frequently or often at school; 61 percent feel unsafe at school, with 30 percent missing at least one day of school in the past month for fear of their safety; and 17 percent are physically assaulted to the point they need medical attention (Kosciw, Greytak, Diaz, & Bartkiewicz, 2010).

The bullying, violence, and other mistreatment experienced by gay teens have significant educational and mental health effects. The most serious consequence is a suicide, as a series of suicides by gay teens in fall 2010 reminded the nation. During that period, three male teenagers in California, Indiana, and Texas killed themselves after reportedly being victims of antigay bullying, and a male college student also killed himself after his roommate broadcast a live video of the student making out with another male (Talbot, 2010).

In other effects, LGBT teens are much more likely than their straight peers to skip school; to do poorly in their studies; to drop out of school; and to experience depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem (Mental Health America, 2011). These mental health problems tend to last at least into their twenties (Russell, Ryan, Toomey, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2011). According to a 2011 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), LGBT teens are also much more likely to engage in risky and/or unhealthy behaviors such as using tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs, having unprotected sex, and even not using a seatbelt (Kann et al., 2011). Commenting on the report, a CDC official said, “This report should be a wake-up call. We are very concerned that these students face such dramatic disparities for so many different health risks” (Melnick, 2011).

Ironically, despite the bullying and another mistreatment that LBGT teens receive at school, they are much more likely to be disciplined for misconduct than straight students accused of similar misconduct. This disparity is greater for girls than for boys. The reasons for the disparity remain unknown but may stem from unconscious bias against gays and lesbians by school officials. As a scholar in educational psychology observed, “To me, it is saying there is some kind of internal bias that adults are not aware of that is impacting the punishment of this group” (St. George, 2010).

Children and Our Future

The Homeless Status of LGBT Teens

Many LGBT teens are taunted, bullied, and otherwise mistreated at school. As the text discusses, this mistreatment affects their school performance and psychological well-being, and some even drop out of school as a result. We often think of the home as a haven from the realities of life, but the lives of many gay teens are often no better at home. If they come out (disclose their sexual orientation) to their parents, one or both parents often reject them. Sometimes they kick their teen out of the home, and sometimes the teen leaves because the home environment has become intolerable. Regardless of the reason, a large number of LGBT teens become homeless. They may be living in the streets, but they may also be living with a friend, at a homeless shelter, or at some other venue. But the bottom line is that they are not living at home with a parent.

The actual number of homeless LGBT teens will probably never be known, but a study in Massachusetts of more than 6,300 high school students was the first to estimate the prevalence of their homelessness using a representative sample. The study found that 25 percent of gay or lesbian teens and 15 percent of bisexual teens are homeless in the state, compared to only 3 percent of heterosexual teens. Fewer than 5 percent of the students in the study identified themselves as LGB, but they accounted for 19 percent of all the homeless students who were surveyed. Regardless of their sexual orientation, some homeless teens live with a parent or guardian, but the study found that homeless LGBT teens were more likely than their heterosexual counterparts to be living without a parent.

Being homeless adds to the problems that many LGBT teens already experience. Regardless of sexual orientation, homeless people of all ages are at greater risk for victimization by robbers and other offenders, hunger, substance abuse, and mental health problems.

The study noted that LGBT teen homelessness may be higher in other states because attitudes about LGBT status are more favorable in Massachusetts than in many other states. Because the study was administered to high school students, it may have undercounted LGBT teens, who are more likely to be absent from school.

These methodological limitations should not obscure the central message of the study as summarized by one of its authors: “The high risk of homelessness among sexual minority teens is a serious problem requiring immediate attention. These teens face enormous risks and all types of obstacles to succeeding in school and are in need of a great deal of assistance.”

Sources: Connolly, 2011; Corliss, Goodenow, Nichols, & Austin, 2011

Employment Discrimination

Federal law prohibits employment discrimination based on race, nationality, sex, or religion. Notice that this list does not include sexual orientation. It is entirely legal under federal law for employers to refuse to hire LGBT individuals or those perceived as LGBT, to fire an employee who is openly LGBT or perceived as LGBT, or to refuse to promote such an employee. Twenty-one states do prohibit employment discrimination based on sexual orientation, but that leaves twenty-nine states that do not prohibit such discrimination. Employers in these states are entirely free to refuse to hire, fire, or refuse to promote LGBT people (openly LGBT or perceived as LGBT) as they see fit. In addition, only fifteen states prohibit employment discrimination based on gender identity (transgender), which leaves thirty-five states in which employers may practice such discrimination (Human Rights Campaign, 2011).

The Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA), which would prohibit job discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity, has been proposed in Congress but has not come close to passing. In response to the absence of legal protection for LGBT employees, many companies have instituted their own policies. As of March 2011, 87 percent of the Fortune 500 companies, the largest 500 corporations in the United States, had policies prohibiting sexual orientation discrimination, and 46 percent had policies prohibiting gender identity discrimination (Human Rights Campaign, 2011).

National survey evidence shows that many LGBT people have, in fact, experienced workplace discrimination (Sears & Mallory, 2011). In the 2008 GSS, 27.1 percent of LGB respondents said they had been verbally harassed at work during the past five years, and 7.1 percent said they had been either fired or not hired during the same period (SDA, 2008). In other surveys that are not based on nationally representative samples, the percentage of LGB respondents who report workplace harassment or discrimination exceeds the GSS’s figures. Not surprisingly, more than one-third of LGB employees say they conceal their sexual orientation in their workplace. Transgender people appear to experience more employment problems than LGB people, as 78 percent of transgender respondents in one study reported some form of workplace harassment or discrimination. Scholars have also conducted field experiments in which they send out resumes or job applicants to prospective employers. The resumes are identical except that some mention the applicant is LGB, while the others do not indicate sexual orientation. The job applicants similarly either say they are LGB or do not say this. The LGB resumes and applicants are less likely than their non-LGB counterparts to receive a positive response from prospective employers.

LGBT people who experience workplace harassment and discrimination suffer in other ways as well (Sears & Mallory, 2011). Compared to LGBT employees who do not experience these problems, they are more likely to have various mental health issues, to be less satisfied with their jobs, and to have more absences from work.

Applying Social Research

How Well Do the Children of Same-Sex Couples Fare?

Many opponents of same-sex marriage claim that children are better off if they are raised by both a mother and a father and that children of same-sex couples fare worse as a result. As the National Organization for Marriage (National Organization for Marriage, 2011) states, “Two men might each be a good father, but neither can be a mom. The ideal for children is the love of their own mom and dad. No same-sex couple can provide that.”

Addressing this contention, social scientists have studied the children of same-sex couples and compared them to the children of heterosexual parents. Although it is difficult to have random, representative samples of same-sex couples’ children, a growing number of studies find that these children fare at least as well psychologically and in other respects as heterosexual couples’ children.

Perhaps the most notable published paper in this area appeared in the American Sociological Review, the preeminent sociology journal, in 2001. The authors, Judith Stacey and Timothy J. Biblarz, reviewed almost two dozen studies that had been done of same-sex couples’ children. All these studies yielded the central conclusion that the psychological well-being of these children is no worse than that of heterosexual couples’ children. As the authors summarized this conclusion and its policy implications, “Because every relevant study to date shows that parental sexual orientation per se has no measurable effect on the quality of parent-child relationships or on children’s mental health or social adjustment, there is no evidentiary basis for considering parental sexual orientation in decisions about children’s ‘best interest.’”

Biblarz and Stacey returned to this issue in a 2010 article in the Journal of Marriage and the Family, the preeminent journal in its field. This time they reviewed almost three dozen studies published since 1990 that compared the children of same-sex couples (most of them lesbian parents) to those of heterosexual couples. They again found that the psychological well-being and social adjustment of same-sex couples’ children was at least as high as those of heterosexual couples’ children, and they even found some evidence that children of lesbian couples fare better in some respects than those of heterosexual couples. Although the authors acknowledged that two parents are generally better for children than one parent, they concluded that the sexual orientation of the parents makes no difference overall. As they summarized the body of research on this issue: “Research consistently has demonstrated that despite prejudice and discrimination children raised by lesbians develop as well as their peers. Across the standard panoply of measures, studies find far more similarities than differences among children with lesbian and heterosexual parents, and the rare differences mainly favor the former.”

This body of research, then, contributes in important ways to the national debate on same-sex marriage. If children of same-sex couples indeed farewell, as the available evidence indicates, concern about these children’s welfare should play no part in this debate.

Same-Sex Marriage

Same-sex marriage has been one of the most controversial social issues in recent years. Nearly 650,000 same-sex couples live together in the United States (Gates, 2012). Many of them would like to marry, but most are not permitted by law to marry. In May 2012, President Obama endorsed same-sex marriage.