15: Working Groups- Performance and Decision Making

- Page ID

- 55077

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

- Define the factors that create social groups.

- Define the concept of social identity, and explain how it applies to social groups.

- Review the stages of group development and dissolution.

- Describe the situations under which social facilitation and social inhibition might occur, and review the theories that have been used to explain these processes.

- Outline the effects of member characteristics, process gains, and process losses on group performance.

- Summarize how social psychologists classify the different types of tasks that groups are asked to perform.

- Explain the influence of each of these concepts on group performance: groupthink, information sharing, brainstorming, and group polarization.

- Review the ways that people can work to make group performance more effective.

15.1 Introduction

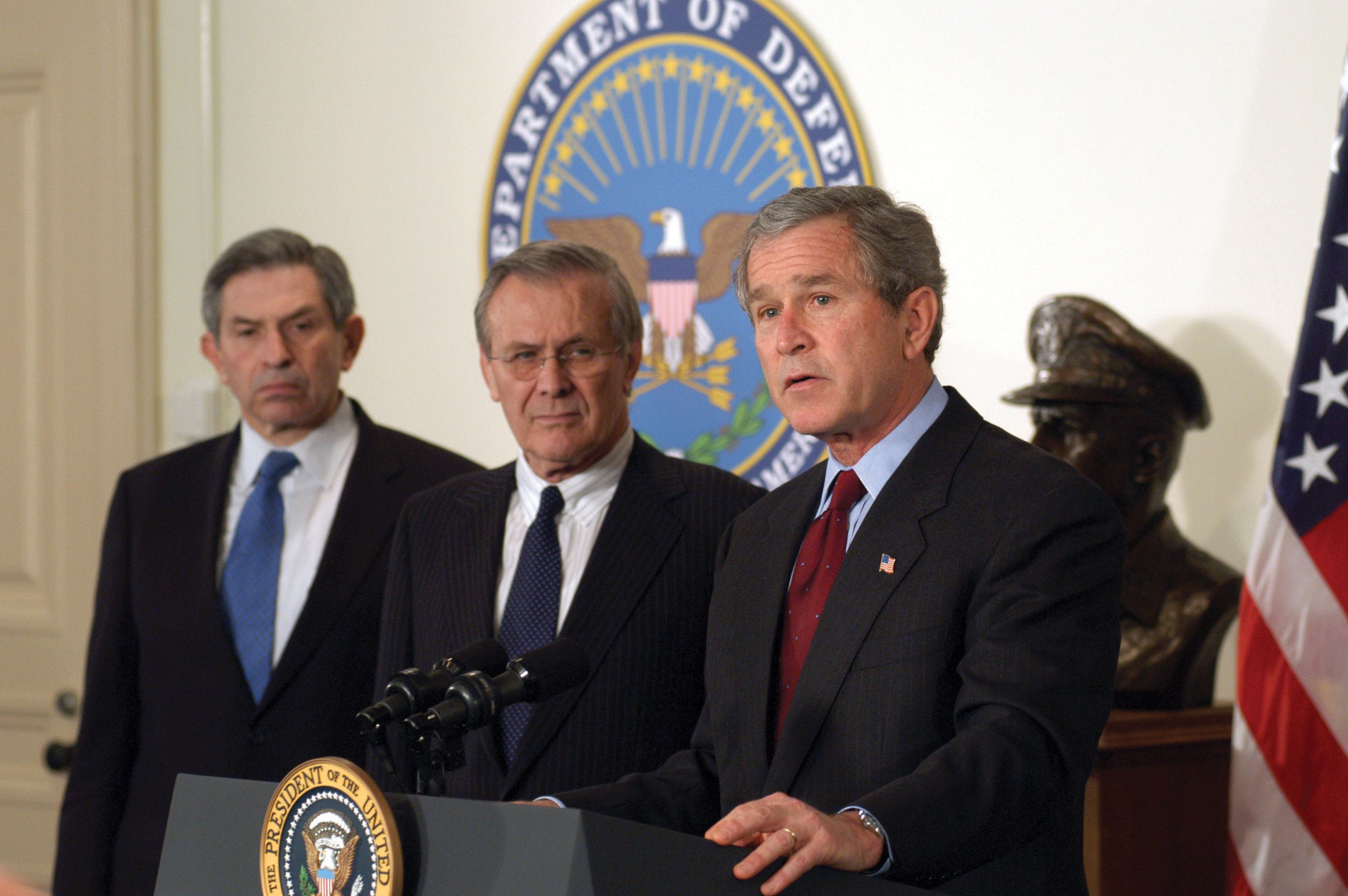

Groupthink and Presidential Decision Making

Wikimedia Commons – CC BY 2.0.

In 2003, President George Bush, in his State of the Union address, made specific claims about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction. The president claimed that there was evidence for “500 tons of sarin, mustard, and VX nerve agent; mobile biological weapons labs” and “a design for a nuclear weapon.” But none of this was true, and in 2004, after the war was started, Bush himself called for an investigation of intelligence failures about such weapons preceding the invasion of Iraq. Many Americans were surprised at the vast failure of intelligence that led the United States into war. In fact, Bush’s decision to go to war based on erroneous facts is part of a long tradition of decision making in the White House. Psychologist Irving Janis popularized the term groupthink in the 1970s to describe the dynamic that afflicted the Kennedy administration when the president and a close-knit band of advisers authorized the ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba in 1961. The president’s view was that the Cuban people would greet the American backed invaders as liberators who would replace Castro’s dictatorship with democracy. In fact, no Cubans greeted the American-backed force as liberators, and Cuba rapidly defeated the invaders. The reasons for the erroneous consensus are easy to understand, at least in hindsight. Kennedy and his advisers largely relied on testimony from Cuban exiles, coupled with a selective reading of available intelligence. As is natural, the president and his advisers searched for information to support their point of view. Those supporting the group’s views were invited into the discussion. In contrast, dissenters were seen as not being team players and had difficulty in getting a hearing. Some dissenters feared to speak loudly, wanting to maintain political influence. As the top team became more selective in gathering information, the bias of information that reached the president became even more pronounced. A few years later, the administration of President Lyndon Johnson became mired in the Vietnam War. The historical record shows that once again, few voices at the very top levels of the administration gave the president the information he needed to make unbiased decisions. Johnson was frequently told that the United States was winning the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese but was rarely informed that most Vietnamese viewed the Americans as occupiers, not liberators. The result was another presidential example of groupthink, with the president repeatedly surprised by military failures. How could a president, a generation after the debacles at the Bay of Pigs and in Vietnam, once again fall prey to the well-documented problem of groupthink? The answer, in the language of former Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill, is that Vice President Dick Cheney and his allies formed “a praetorian guard that encircled the president” to block out views they did not like. Unfortunately, filtering dissent is associated with more famous presidential failures than

spectacular successes.

Source: Levine, D. I. (2004, February 5). Groupthink and Iraq. San Francisco Chronicle.

Retrieved from http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-

bin/article.cgi?file=/chronicle/archive/2004/02/05/EDGV34OCEP1.DTL.

Although people and their worlds have changed dramatically over the course of our history, one

fundamental aspect of human existence remains essentially the same. Just as our primitive

ancestors lived together in small social groups of families, tribes, and clans, people today still

spend a great deal of time in social groups. We go to bars and restaurants, we study together in

groups, and we work together on production lines and in businesses. We form governments, play

together on sports teams, and use Internet chat rooms and user groups to communicate with

others. It seems that no matter how much our world changes, humans will always remain social

creatures. It is probably not incorrect to say that the human group is the very foundation of

human existence; without our interactions with each other, we would simply not be people, and

there would be no human culture.

We can define a social group as a set of individuals with a shared purpose and who normally

share a positive social identity. While social groups form the basis of human culture and

productivity, they also produce some of our most profound disappointments. Groups sometimes

create the very opposite of what we might hope for, such as when a group of highly intelligent

advisers lead their president to make a poor decision when a peaceful demonstration turns into a

violent riot, or when the members of a clique at a high school tease other students until they

become violent.

In this chapter, we will first consider how social psychologists define social groups. We will also see that effective group decision making is important in business, education, politics, law, and many

other areas (Kovera & Borgida, 2010; Straus, Parker, & Bruce, 2011). We will close the chapter

with a set of recommendations for improving group performance. Taking all the data together, one psychologist once went so far as to comment that “humans would do better without groups!” (Buys, 1978). What Buys probably meant by this comment, I think, was to acknowledge the enormous force of social groups and to point out the importance of being aware that these forces can have both positive and negative consequences (Allen & Hecht, 2004; Kozlowski & Ilgen, 2006; Larson, 2010; Levi, 2007; Nijstad, 2009). Keep this important idea in mind as you read this chapter.

References

Allen, N. J., & Hecht, T. D. (2004). The “romance of teams”: Toward an understanding of its

psychological underpinnings and implications. Journal of Occupational and Organizational

Psychology, 77(4), 439–461. doi: 10.1348/0963179042596469.

Buys, B. J. (1978). Humans would do better without groups. Personality and Social Psychology

Bulletin, 4, 123–125.

Kovera, M. B., & Borgida, E. (2010). Social psychology and law. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, &

G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (5th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 1343–1385). Hoboken,

NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Kozlowski, S. W. J., & Ilgen, D. R. (2006). Enhancing the effectiveness of work groups and

teams. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 7(3), 77–124. doi:

10.1111/j.1529–1006.2006.00030.x.

Larson, J. R., Jr. (2010). In search of synergy in small group performance. New York, NY:

Psychology Press; Levi, D. (2007). Group dynamics for teams (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA:

Sage

Nijstad, B. A. (2009). Group performance. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Straus, S. G., Parker, A. M., & Bruce, J. B. (2011). The group matters: A review of processes

and outcomes in intelligence analysis. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 15(2),

128–146.

15.2 Understanding Social Groups

Although it might seem that we could easily recognize a social group when we come across one, it is actually not that easy to define what makes a group of people a social group. Imagine, for instance, a half dozen people waiting in a checkout line at a supermarket. You would probably agree that this set of individuals should not be considered a social group because the people are not meaningfully related to each other. And the individuals watching a movie at a theater or those attending a large lecture class might also be considered simply as individuals who are in the same place at the same time but who are not connected as a social group.

Of course, a group of individuals who are currently in the same place may nevertheless easily turn into a social group if something happens that brings them “together.” For instance, if a man in the checkout line of the supermarket suddenly collapsed on the floor, it is likely that the others around him would quickly begin to work together to help him. Someone would call an ambulance, another might give CPR, and another might attempt to contact his family. Similarly, if the movie theater were to catch on fire, a group would quickly form as the individuals attempted to leave the theater. And even the class of students might come to feel like a group if the instructor continually praised it for being the best (or the worst) class that she has ever had. It has been a challenge to characterize what the “something” is that makes a group a group, but one term that has been used is entitativity (Campbell, 1958; Lickel et al., 2000). Entitativity refers to something like “groupiness”—the perception, either by the group members themselves or by others, that the people together are a group.

References

Campbell, D. T. (1958). Common fate, similarity, and other indices of the status of aggregate persons as social entities. Behavioral Science, 3, 14–25.

Crump, S. A., Hamilton, D. L., Sherman, S. J., Lickel, B., & Thakkar, V. (2010). Group entitativity and similarity: Their differing patterns in perceptions of groups. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(7), 1212–1230. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.716.

Deutsch, M. (1949). An experimental study of the effects of cooperation and competition upon group processes. Human Relations, 2, 199–231.

Gersick, C. (1989). Marking time: Predictable transitions in task groups. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 274–309.

Gersick, C. J. (1988). Time and transition in work teams: Toward a new model of group development. Academy of Management Journal, 31(1), 9–41.

Hogg, M. A. (2003). Social identity. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (pp. 462–479). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hogg, M. A. (2010). Human groups, social categories, and collective self: Social identity and the management of self-uncertainty. In R. M. Arkin, K. C. Oleson, & P. J. Carroll (Eds.), Handbook of the uncertain self (pp. 401–420). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Kuypers, B. C., Davies, D., & Hazewinkel, A. (1986). Developmental patterns in self-analytic groups. Human Relations, 39(9), 793–815.

Lickel, B., Hamilton, D. L., Wieczorkowska, G., Lewis, A., Sherman, S. J., & Uhles, A. N. (2000). Varieties of groups and the perception of group entitativity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(2), 223–246.

Miles, J. R., & Kivlighan, D. M., Jr. (2008). Team cognition in group interventions: The relation between coleaders’ shared mental models and group climate. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 12(3), 191–209. doi: 10.1037/1089–2699.12.3.191.

Rispens, S., & Jehn, K. A. (2011). Conflict in workgroups: Constructive, destructive, and asymmetric conflict. In D. De Cremer, R. van Dick, & J. K. Murnighan (Eds.), Social psychology and organizations (pp. 185–209). New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

15.3 Group Process: the Pluses & Minuses of Working Together

When important decisions need to be made, or when tasks need to be performed quickly or effectively, we frequently create groups to accomplish them. Many people believe that groups are effective for making decisions and performing other tasks (Nijstad, Stroebe, & Lodewijkx, 2006), and such a belief seems commonsensical. After all, because groups have many members, they will also have more resources and thus more ability to efficiently perform tasks and make good decisions. However, although groups sometimes do perform better than individuals, this outcome is not guaranteed. Let’s consider some of the many variables that can influence group performance.

References

Abrams, D., Wetherell, M., Cochrane, S., & Hogg, M. (1990). Knowing what to think by knowing who you are: Self-categorization and the nature of norm formation, conformity, and group polarization. British Journal of Social Psychology, 29, 97–119.

Armstrong, J. S. (2001). Principles of forecasting: A handbook for researchers and practitioners. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Baron, R. S. (2005). So right it’s wrong: Groupthink and the ubiquitous nature of polarized group decision making. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 37, pp. 219–253). San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press.

Baumeister, R. F., & Steinhilber, A. (1984). Paradoxical effects of supportive audiences on performance under pressure: The home field disadvantage in sports championships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(1), 85–93.

Bond, C. F., & Titus, L. J. (1983). Social facilitation: A meta-analysis of 241 studies. Psychological Bulletin, 94(2), 265–292.

Bornstein, B. H., & Greene, E. (2011). Jury decision making: Implications for and from psychology. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(1), 63–67.

Brauer, M., Judd, C. M., & Gliner, M. D. (2006). The effects of repeated expressions on attitude polarization during group discussions. In J. M. Levine & R. L. Moreland (Eds.), Small groups (pp. 265–287). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Cheng, P.-Y., & Chiou, W.-B. (2008). Framing effects in group investment decision making: Role of group polarization. Psychological Reports, 102(1), 283–292.

Clark, R. D., Crockett, W. H., & Archer, R. L. (1971). Risk-as-value hypothesis: The relationship between perception of self, others, and the risky shift. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 20, 425–429.

Clayton, M. J. (1997). Delphi: A technique to harness expert opinion for critical decision-making tasks in education. Educational Psychology, 17(4), 373–386. doi: 10.1080/0144341970170401.

Collaros, P. A., & Anderson, I. R. (1969). Effect of perceived expertness upon creativity of members of brainstorming groups. Journal of Applied Psychology, 53, 159–163.

Connolly, T., Routhieaux, R. L., & Schneider, S. K. (1993). On the effectiveness of group brainstorming: Test of one underlying cognitive mechanism. Small Group Research, 24(4), 490–503.

Delbecq, A. L., Van de Ven, A. H., & Gustafson, D. H. (1975). Group techniques for program planning: A guide to nominal group and delphi processes. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman.

Dennis, A. R., & Valacich, J. S. (1993). Computer brainstorms: More heads are better than one. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 531–537.

Devine, D. J., Olafson, K. M., Jarvis, L. L., Bott, J. P., Clayton, L. D., & Wolfe, J. M. T. (2004). Explaining jury verdicts: Is leniency bias for real? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(10), 2069–2098.

Diehl, M., & Stroebe, W. (1987). Productivity loss in brainstorming groups: Toward the solution of a riddle. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(3), 497–509.

Diehl, M., & Stroebe, W. (1991). Productivity loss in idea-generating groups: Tracking down the blocking effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(3), 392–403.

Drummond, J. T. (2002). From the Northwest Imperative to global jihad: Social psychological aspects of the construction of the enemy, political violence, and terror. In C. E. Stout (Ed.), The psychology of terrorism: A public understanding (Vol. 1, pp. 49–95). Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group.

Einhorn, H. J., Hogarth, R. M., & Klempner, E. (1977). Quality of group judgment. Psychological Bulletin, 84(1), 158–172.

Ellsworth, P. C. (1993). Some steps between attitudes and verdicts. In R. Hastie (Ed.), Inside the juror: The psychology of juror decision making. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Faulmüller, N., Kerschreiter, R., Mojzisch, A., & Schulz-Hardt, S. (2010). Beyond group-level explanations for the failure of groups to solve hidden profiles: The individual preference effect revisited. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 13(5), 653–671.

Gabrenya, W. K., Wang, Y., & Latané, B. (1985). Social loafing on an optimizing task: Cross-cultural differences among Chinese and Americans. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 16(2), 223–242.

Gallupe, R. B., Cooper, W. H., Grise, M.-L., & Bastianutti, L. M. (1994). Blocking electronic brainstorms. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(1), 77–86.

Geen, R. G. (1989). Alternative conceptions of social facilitation. In P. Paulus (Ed.), Psychology of group influence (2nd ed., pp. 15–51). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Guerin, B. (1983). Social facilitation and social monitoring: A test of three models. British Journal of Social Psychology, 22(3), 203–214.

Hackman, J., & Morris, C. (1975). Group tasks, group interaction processes, and group performance effectiveness: A review and proposed integration. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 8, pp. 45–99). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Hastie, R. (1993). Inside the juror: The psychology of juror decision making. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Hastie, R. (2008). What’s the story? Explanations and narratives in civil jury decisions. In B. H. Bornstein, R. L. Wiener, R. Schopp, & S. L. Willborn (Eds.), Civil juries and civil justice: Psychological and legal perspectives (pp. 23–34). New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media.

Hastie, R., Penrod, S. D., & Pennington, N. (1983). Inside the jury. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hinsz, V. B. (1990). Cognitive and consensus processes in group recognition memory performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(4), 705–718.

Hogg, M. A., Turner, J. C., & Davidson, B. (1990). Polarized norms and social frames of reference: A test of the self-categorization theory of group polarization. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 11(1), 77–100.

Hornsby, J. S., Smith, B. N., & Gupta, J. N. D. (1994). The impact of decision-making methodology on job evaluation outcomes: A look at three consensus approaches. Group and Organization Management, 19(1), 112–128.

Janis, I. L. (2007). Groupthink. In R. P. Vecchio (Ed.), Leadership: Understanding the dynamics of power and influence in organizations (2nd ed., pp. 157–169). Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Jones, M. B. (1974). Regressing group on individual effectiveness. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 11(3), 426–451.

Karau, S. J., & Williams, K. D. (1993). Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(4), 681–706.

Kelley, H. H., Condry, J. C., Jr., Dahlke, A. E., & Hill, A. H. (1965). Collective behavior in a simulated panic situation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 1, 19–54.

Kerr, N. L. (1978). Severity of prescribed penalty and mock jurors’ verdicts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36(12), 1431–1442.

Kogan, N., & Wallach, M. A. (1967). Risky-shift phenomenon in small decision-making groups: A test of the information-exchange hypothesis. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 3, 75–84.

Kramer, R. M. (1998). Revisiting the Bay of Pigs and Vietnam decisions 25 years later: How well has the groupthink hypothesis stood the test of time? Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 73(2–3), 236–271.

Kravitz, D. A., & Martin, B. (1986). Ringelmann rediscovered: The original article. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 936–941.

Larson, J. R. J., Foster-Fishman, P. G., & Keys, C. B. (1994). The discussion of shared and unshared information in decision-making groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 446–461.

Latané, B., Williams, K., & Harkins, S. (1979). Many hands make light the work: The causes and consequences of social loafing. Journal of Personality and social Psychology, 37(6), 822–832.

Lieberman, J. D. (2011). The utility of scientific jury selection: Still murky after 30 years. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(1), 48–52.

Lorge, I., Fox, D., Davitz, J., & Brenner, M. (1958). A survey of studies contrasting the quality of group performance and individual performance. Psychological Bulletin, 55(6), 337–372.

MacCoun, R. J., & Kerr, N. L. (1988). Asymmetric influence in mock jury deliberation: Jurors’ bias for leniency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(1), 21–33.

Mackie, D. M. (1986). Social identification effects in group polarization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(4), 720–728.

Mackie, D. M., & Cooper, J. (1984). Attitude polarization: Effects of group membership. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 575–585.

Markus, H. (1978). The effect of mere presence on social facilitation: An unobtrusive test. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 14, 389–397.

McCauley, C. R. (1989). Terrorist individuals and terrorist groups: The normal psychology of extreme behavior. In J. Groebel & J. H. Goldstein (Eds.), Terrorism: Psychological perspectives (p. 45). Sevilla, Spain: Universidad de Sevilla.

Mesmer-Magnus, J. R., DeChurch, L. A., Jimenez-Rodriguez, M., Wildman, J., & Shuffler, M. (2011). A meta-analytic investigation of virtuality and information sharing in teams. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 115(2), 214–225.

Mojzisch, A., & Schulz-Hardt, S. (2010). Knowing others’ preferences degrades the quality of group decisions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(5), 794–808.

Myers, D. G. (1982). Polarizing effects of social interaction. In H. Brandstatter, J. H. Davis, & G. Stocher-Kreichgauer (Eds.), Contemporary problems in group decision-making (pp. 125–161). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Myers, D. G., & Bishop, G. D. (1970). Discussion effects on racial attitudes. Science, 169(3947), 778–779. doi: 10.1126/science.169.3947.778.

Myers, D. G., & Kaplan, M. F. (1976). Group-induced polarization in simulated juries. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2(1), 63–66.

Najdowski, C. J. (2010). Jurors and social loafing: Factors that reduce participation during jury deliberations. American Journal of Forensic Psychology, 28(2), 39–64.

Nijstad, B. A., Stroebe, W., & Lodewijkx, H. F. M. (2006). The illusion of group productivity: A reduction of failures explanation. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36(1), 31–48. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.295.

Osborn, A. F. (1953). Applied imagination. Oxford, England: Scribner’s.

Paulus, P. B., & Dzindolet, M. T. (1993). Social influence processes in group brainstorming. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(4), 575–586.

Petty, R. E., Harkins, S. G., Williams, K. D., & Latané, B. (1977). The effects of group size on cognitive effort and evaluation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 3(4), 579–582.

Reimer, T., Reimer, A., & Czienskowski, U. (2010). Decision-making groups attenuate the discussion bias in favor of shared information: A meta-analysis. Communication Monographs, 77(1), 121–142.

Reimer, T., Reimer, A., & Hinsz, V. B. (2010). Naïve groups can solve the hidden-profile problem. Human Communication Research, 36(3), 443–467.

Robinson-Staveley, K., & Cooper, J. (1990). Mere presence, gender, and reactions to computers: Studying human-computer interaction in the social context. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 26(2), 168–183.

Siau, K. L. (1995). Group creativity and technology. Psychosomatics, 31, 301–312.

Stasser, G. M., & Taylor, L. A. (1991). Speaking turns in face-to-face discussions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 675–684.

Stasser, G., & Stewart, D. (1992). Discovery of hidden profiles by decision-making groups: Solving a problem versus making a judgment. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 63, 426–434.

Stasser, G., & Titus, W. (1985). Pooling of unshared information in group decision making: Biased information sampling during discussion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(6), 1467–1478.

Stasser, G., Kerr, N. L., & Bray, R. M. (1982). The social psychology of jury deliberations: Structure, process and product. In N. L. Kerr & R. M. Bray (Eds.), The psychology of the courtroom (pp. 221–256). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Stasser, G., Taylor, L. A., & Hanna, C. (1989). Information sampling in structured and unstructured discussions of three- and six-person groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(1), 67–78.

Stein, M. I. (1978). Methods to stimulate creative thinking. Psychiatric Annals, 8(3), 65–75.

Stoner, J. A. (1968). Risky and cautious shifts in group decisions: The influence of widely held values. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 4, 442–459.

Straus, S. G. (1999). Testing a typology of tasks: An empirical validation of McGrath’s (1984) group task circumplex. Small Group Research, 30(2), 166–187. doi: 10.1177/104649649903000202.

Stroebe, W., & Diehl, M. (1994). Why groups are less effective than their members: On productivity losses in idea-generating groups. European Review of Social Psychology, 5, 271–303.

Strube, M. J., Miles, M. E., & Finch, W. H. (1981). The social facilitation of a simple task: Field tests of alternative explanations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 7(4), 701–707.

Surowiecki, J. (2004). The wisdom of crowds: Why the many are smarter than the few and how collective wisdom shapes business, economies, societies, and nations (1st ed.). New York, NY: Doubleday.

Szymanski, K., & Harkins, S. G. (1987). Social loafing and self-evaluation with a social standard. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(5), 891–897.

Triplett, N. (1898). The dynamogenic factors in pacemaking and competition. American Journal of Psychology, 9(4), 507–533.

Valacich, J. S., Jessup, L. M., Dennis, A. R., & Nunamaker, J. F. (1992). A conceptual framework of anonymity in group support systems. Group Decision and Negotiation, 1(3), 219–241.

Van Swol, L. M. (2009). Extreme members and group polarization. Social Influence, 4(3), 185–199.

Vinokur, A., & Burnstein, E. (1978). Novel argumentation and attitude change: The case of polarization following group discussion. European Journal of Social Psychology, 8(3), 335–348.

Weber, B., & Hertel, G. (2007). Motivation gains of inferior group members: A meta-analytical review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(6), 973–993.

Williams, K. D., Nida, S. A., Baca, L. D., & Latane, B. (1989). Social loafing and swimming: Effects of identifiability on individual and relay performance of intercollegiate swimmers. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 10(1), 73–81.

Winter, R. J., & Robicheaux, T. (2011). Questions about the jury: What trial consultants should know about jury decision making. In R. L. Wiener & B. H. Bornstein (Eds.), Handbook of trial consulting (pp. 63–91). New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media.

Wittenbaum, G. M. (1998). Information sampling in decision-making groups: The impact of members’ task-relevant status. Small Group Research, 29(1), 57–84.

Zajonc, R. B. (1965). Social facilitation. Science, 149, 269–274.

Zajonc, R. B., Heingartner, A., & Herman, E. M. (1969). Social enhancement and impairment of performance in the cockroach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13(2), 83–92.

Zhu, H. (2009). Group polarization on corporate boards: Theory and evidence on board decisions about acquisition premiums, executive compensation, and diversification. (Doctoral dissertation). University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

15.4 Improving Group Performance

As we have seen, it makes sense to use groups to make decisions because people can create outcomes working together that any one individual could not hope to accomplish alone. In addition, once a group makes a decision, the group will normally find it easier to get other people to implement it because many people feel that decisions made by groups are fairer than those made by individuals. And yet, as we have also seen, there are also many problems associated with groups that make it difficult for them to live up to their full potential. In this section, let’s consider this issue more fully: What approaches can we use to make best use of the groups that we belong to, helping them to achieve as best as is possible? Training groups to perform more effectively is possible if appropriate techniques are used (Salas et al., 2008).

Perhaps the first thing we need to do is to remind our group members that groups are not as effective as they sometimes seem. Group members often think that their group is being more productive than it really is and that their own groups are particularly productive. For instance, people who participate in brainstorming groups report that they have been more productive than those who work alone, even if the group has actually not done all that well (Paulus, Dzindolet, Poletes, & Camacho, 1993; Stroebe, Diehl, & Abakoumkin, 1992).

The tendency to overvalue the productivity of groups is known as the illusion of group effectivity, and it seems to occur for several reasons. For one, the productivity of the group as a whole is highly accessible, and this productivity generally seems quite good, at least in comparison with the contributions of single individuals. The group members hear many ideas expressed by themselves and the other group members, and this gives the impression that the group is doing very well, even if objectively it is not. And on the affective side, group members receive a lot of positive social identity from their group memberships. These positive feelings naturally lead them to believe that the group is strong and performing well. Thus the illusion of group effectivity poses a severe problem for group performance, and we must work to make sure that group members are aware of it. Just because we are working in groups does not mean that we are making good decisions or performing a task particularly well—group members, and particularly the group leader, must always monitor group performance and attempt to motivate the group to work harder.

References

Bantel, K. A., & Jackson, S. E. (1989). Top management and innovations in banking: Does the composition of the top team make a difference? Strategy Management Journal, 10(S1), 107–124.

Baron, J., & Pfefer, J. (1994). The social psychology of organizations and inequality. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57(3), 190–209.

Bond, M. A., & Keys, C. B. (1993). Empowerment, diversity, and collaboration: Promoting synergy on community boards. American Journal of Community Psychology, 21, 37–57.

Bond, M. H., & Shiu, W. Y.-F. (1997). The relationship between a group’s personality resources and the two dimensions of its group process. Small Group Research, 28(2), 194–217.

Crisp, R. J., & Turner, R. N. (2011). Cognitive adaptation to the experience of social and cultural diversity. Psychological Bulletin, 137(2), 242–266. doi: 10.1037/a002184.

Geurts, S. A., Buunk, B. P., & Schaufeli, W. B. (1994). Social comparisons and absenteeism: A structural modeling approach. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 24(21), 1871–1890.

Graves, L. M., & Powell, G. M. (1995). The effect of sex similarity on recruiters’ evaluations of actual applicants: A test of the similarity-attraction paradigm. Personnel Psychology, 48, 85–98.

Gurin, P., Peng, T., Lopez, G., & Nagda, B. A. (1999). Context, identity, and intergroup relations. In D. A. Prentice & D. T. Miller (Eds.), Cultural divides: Understanding and overcoming group conflict (pp. 133–170). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Hackman, J., & Morris, C. (1975). Group tasks, group interaction processes, and group performance effectiveness: A review and proposed integration. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 8, pp. 45–99). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Hardy, C. J., & Latané, B. (1988). Social loafing in cheerleaders: Effects of team membership and competition. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 10(1), 109–114.

Harkins, S. G., & Petty, R. E. (1982). Effects of task difficulty and task uniqueness on social loafing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(6), 1214–1229.

Haslam, S. A., Wegge, J., & Postmes, T. (2009). Are we on a learning curve or a treadmill? The benefits of participative group goal setting become apparent as tasks become increasingly challenging over time. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39(3), 430–446.

Hinsz, V. B. (1995). Goal setting by groups performing an additive task: A comparison with individual goal setting. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25(11), 965–990.

Jackson, S. E., & Joshi, A. (2011). Work team diversity. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, Vol 1: Building and developing the organization. (pp. 651–686). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Kanter, R. M. (1977). Some effects of proportions on group life: Skewed sex ratios and responses to token women. American Journal of Sociology, 82, 965–990.

Karau, S. J., & Williams, K. D. (1993). Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(4), 681–706.

Kerr, N. L., & Bruun, S. E. (1981). Ringelmann revisited: Alternative explanations for the social loafing effect. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 7(2), 224–231.

Kerr, N. L., & Bruun, S. E. (1983). Dispensability of member effort and group motivation losses: Free-rider effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(1), 78–94.

Kim, Y. Y. (1988). Communication and cross cultural adaptation: A stereotype challenging theory. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

Kruglanski, A. W., & webster, D. M. (1991). Group members’ reactions to opinion deviates and conformists at varying degrees of proximity to decision deadline and of environmental noise. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 212–225.

Latané, B., Williams, K., & Harkins, S. (1979). Many hands make light the work: The causes and consequences of social loafing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(6), 822–832.

Latham, G. P., & Locke, E. A. (1991). Self-regulation through goal setting. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 212–247.

Latham, G. P., Winters, D. C., & Locke, E. A. (1994). Cognitive and motivational effects of participation: A mediator study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15(1), 49–63.

Little, B. L., & Madigan, R. M. (1997). The relationship between collective efficacy and performance in manufacturing work teams. Small Group Research, 28(4), 517–534.

Locke, E., & Latham, G. (1990). A theory of goal setting and task performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

McLeod, P. L., Lobel, S. A., & Cox, T. H. (1996). Ethnic diversity and creativity in small groups. Small Group Research, 27(2), 248–264.

Miller, N., & Davidson-Podgorny, G. (1987). Theoretical models of intergroup relations and the use of cooperative teams as an intervention for desegregated settings in Review of Personality and Social Psychology. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Mullen, B., & Baumeister, R. F. (1987). Group effects on self-attention and performance: Social loafing, social facilitation, and social impairment. In C. Hendrick (Ed.), Group processes and intergroup relations (pp. 189–206). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mullen, B., Symons, C., Hu, L.-T., & Salas, E. (1989). Group size, leadership behavior, and subordinate satisfaction. Journal of General Psychology, 116(2), 155–170.

Nemeth, C., Brown, K., & Rogers, J. (2001). Devil’s advocate versus authentic dissent: Stimulating quantity and quality. European Journal of Social Psychology, 31(6), 707–720. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.58.

Nishii, L. H., & Mayer, D. M. (2009). Do inclusive leaders help to reduce turnover in diverse groups? The moderating role of leader–member exchange in the diversity to turnover relationship. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(6), 1412–1426. doi: 10.1037/a0017190.

Paulus, P. B., Dzindolet, M. T., Poletes, G., & Camacho, L. M. (1993). Perception of performance in group brainstorming: The illusion of group productivity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 19(1), 78–89.

Platow, M. J., O’Connell, A., Shave, R., & Hanning, P. (1995). Social evaluations of fair and unfair allocators in interpersonal and intergroup situations. British Journal of Social Psychology, 34(4), 363–381.

Salas, E., Diaz-Granados, D., Klein, C., Burke, C. S., Stagl, K. C., Goodwin, G. F., & Halpin, S. M. (2008). Does team training improve team performance? A meta-analysis. Human Factors, 50(6), 903–933.

Silver, W. S., & Bufanio, K. M. (1996). The impact of group efficacy and group goals on group task performance. Small Group Research, 27(3), 347–359.

Silver, W. S., & Bufanio, K. M. (1997). Reciprocal relationships, causal influences, and group efficacy: A reply to Kaplan. Small Group Research, 28(4), 559–562.

Stroebe, W., Diehl, M., & Abakoumkin, G. (1992). The illusion of group effectivity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(5), 643–650.

Tsui, A. S., Egan, T. D., & O’Reilly, C. A. (1992). Being different: Relational demography and organizational attachment. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37(4), 549–579.

van Knippenberg, D., & Schippers, M. C. (2007). Work group diversity. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 515–541.

Wagner, W., Pfeffer, J., & O’Reilly, C. I. (1984). Organizational demography and turnover in top management groups. Administrative Science Quarterly, 29, 74–92.

Weldon, E., & Weingart, L. R. (1993). Group goals and group performance. British Journal of Social Psychology, 32, 307–334.

Weldon, E., Jehn, K. A., & Pradhan, P. (1991). Processes that mediate the relationship between a group goal and improved group performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(4), 555–569.

Williams, K., Harkins, S. G., & Latané, B. (1981). Identifiability as a deterrant to social loafing: Two cheering experiments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40(2), 303–311.

Wood, W. (1987). Meta-analytic review of sex differences in group performance. Psychological Bulletin, 102(1), 53–71. doi: 10.1037/0033–2909.102.1.53.

Yetton, P., & Bottger, P. (1983). The relationships among group size, member ability, social decision schemes, and performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 32(2), 145–159.

15.5 Thinking Like A Social Psychologist About Social Groups

This chapter has looked at the ways in which small working groups come together to perform tasks and make decisions. I hope you can see now, perhaps better than you were able to before, the advantages and disadvantages of using groups. Although groups can perform many tasks well, and although people like to use groups to make decisions, groups also come with their own problems.

Since you are likely to spend time working with others in small groups—almost everyone does—I hope that you can now see how groups can succeed and how they can fail. Will you use your new knowledge about social groups to help you be a more effective group member and to help the groups you work in become more effective?

Because you are thinking like a social psychologist, you will realize that groups are determined in part by their personalities—that is, the member characteristics of the group. But you also know that this is not enough and that group performance is also influenced by what happens in the group itself. Groups may become too sure of themselves, too full of social identity and with strong conformity pressures, making it difficult for them to succeed. Can you now see the many ways that you—either as a group member or as a group leader—can help prevent these negative outcomes?

Your value as a group member will increase when you make use of your knowledge about groups. You now have many ideas about how to recognize groupthink and group polarization when they occur and how to prevent them. And you can now see how important group discussion is. When you are in a group, you must work to get the group to talk about the topics fully, even if the group members feel that they have already done enough. Groups think that they are doing better than they really are, and you must work to help them overcome this overconfidence.

15.6 End-of-Chapter Summary

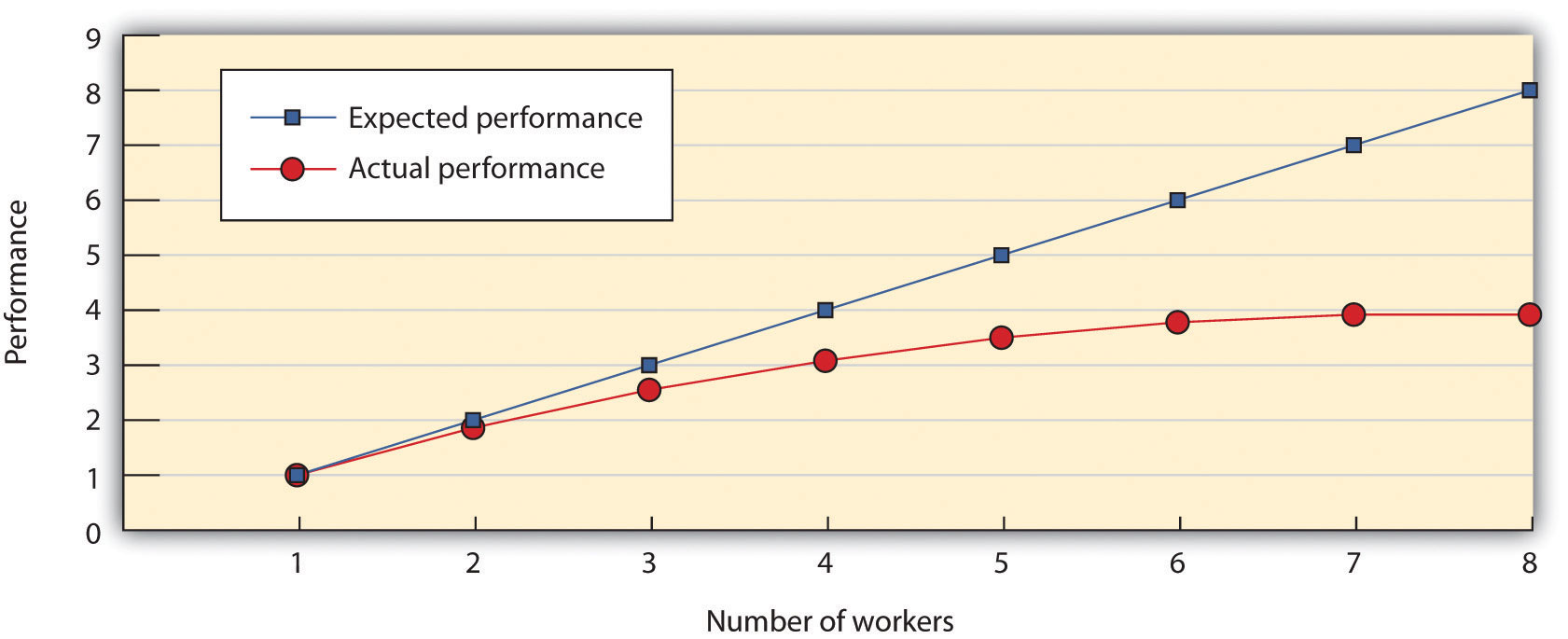

This chapter has focused on the decision making and performance of small working groups. Because groups consist of many members, group performance is almost always better, and group decisions generally more accurate, than that of any individual acting alone. On the other hand, there are also costs to working in groups—we call them process losses.

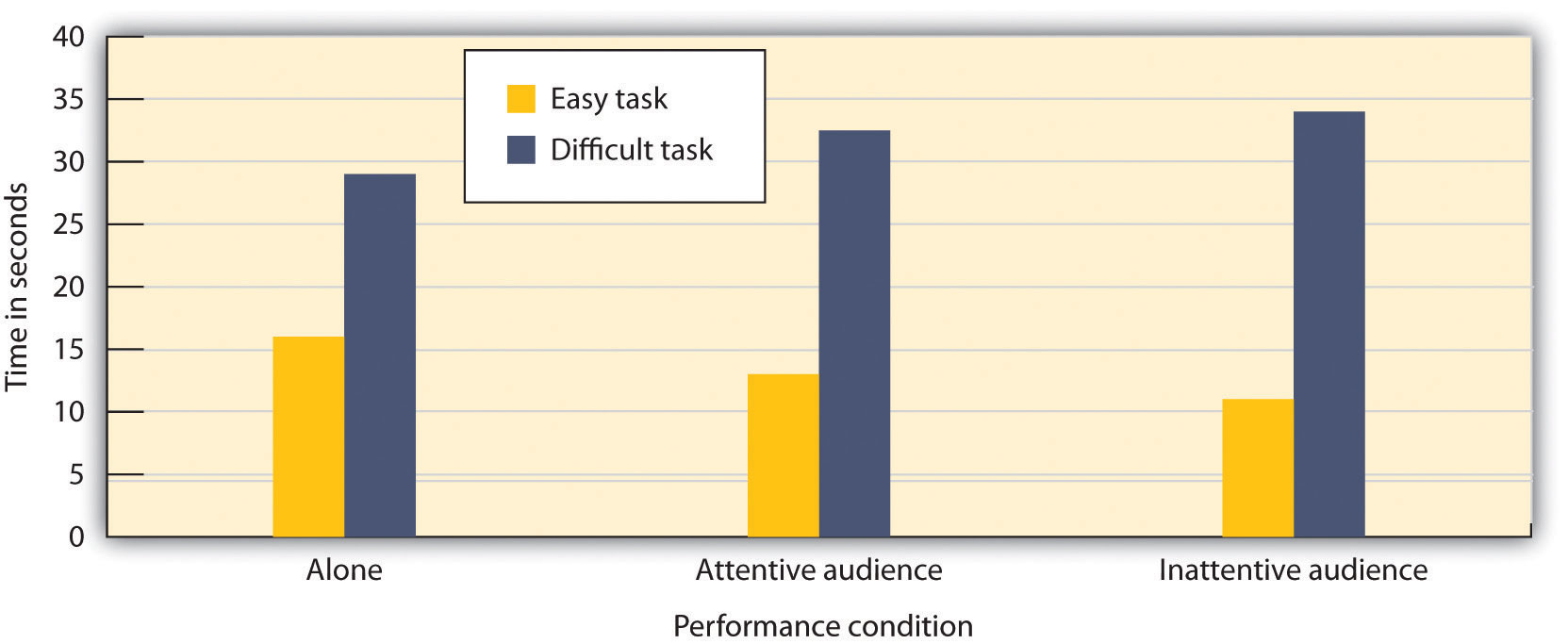

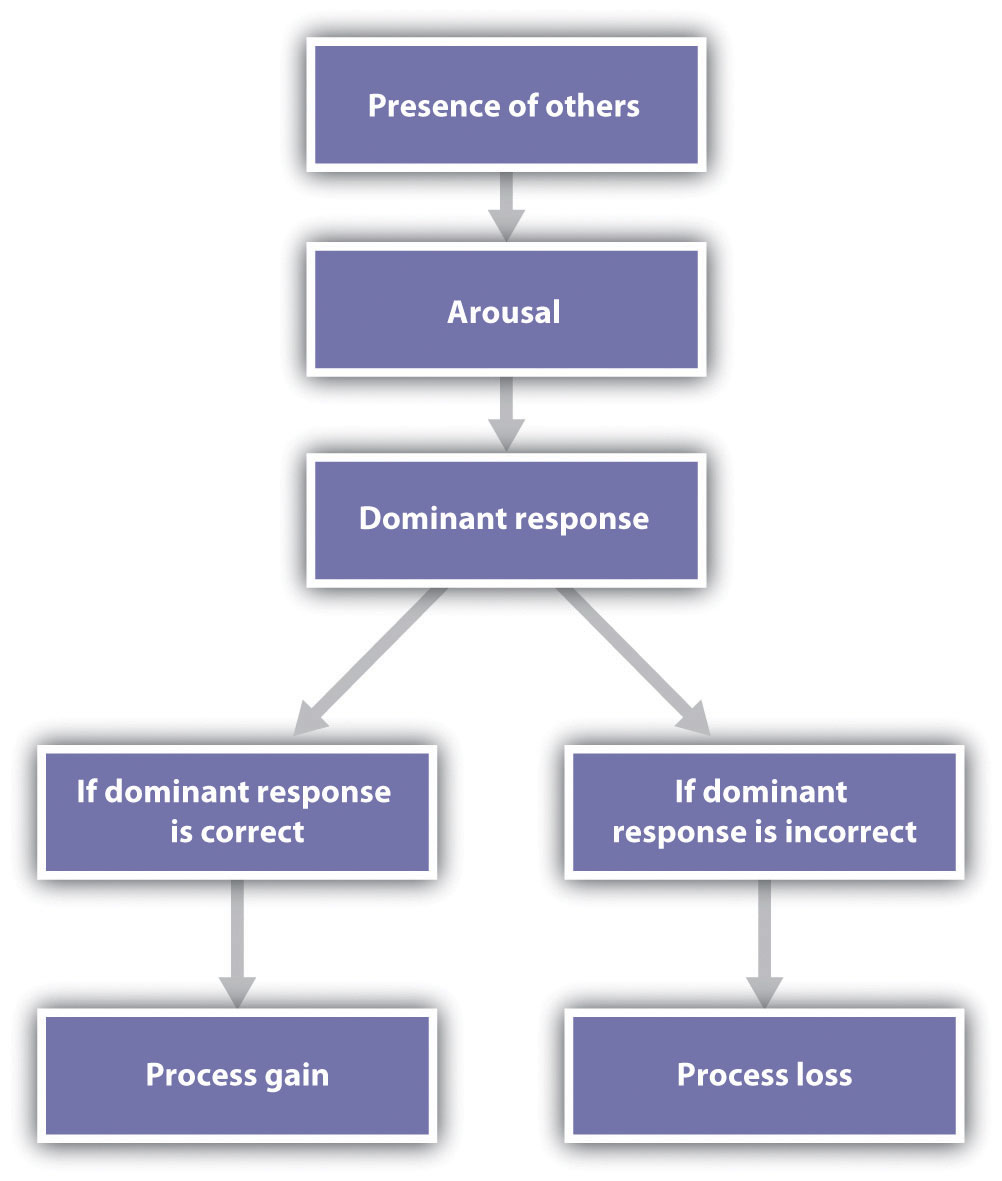

A variety of research has found that the presence of others can create social facilitation—an increase in task performance—on many types of tasks. However, the presence of others sometimes creates poorer individual performance—social inhibition. According to Robert Zajonc’s explanation for the difference, when we are with others, we experience more arousal than we do when we are alone, and this arousal increases the likelihood that we will perform the dominant response—the action that we are most likely to emit in any given situation. Although the arousal model proposed by Zajonc is perhaps the most elegant, other explanations have also been proposed to account for social facilitation and social inhibition.

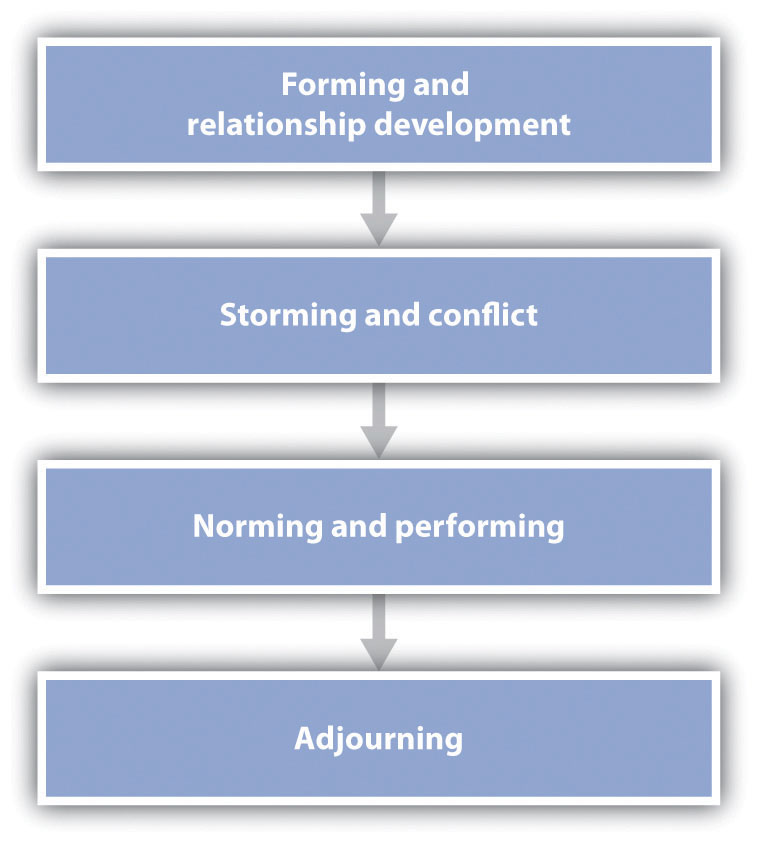

One determinant of the perception of a group is a cognitive one—the perception of similarity. A group can only be a group to the extent that its members have something in common. A group also has more entitativity when the group members have frequent interaction and communication with each other. Interaction is particularly important when it is accompanied by interdependence—the extent to which the group members are mutually dependent upon each other to reach a goal. And a group that develops group structure is also more likely to be seen as a group. The affective feelings that we have toward the group we belong to—social identity—also help to create an experience of a group. Most groups pass through a series of stages—forming, storming, norming and performing, and adjourning—during their time together.

We can compare the potential productivity of the group—that is, what the group should be able to do, given its membership—with the actual productivity of the group by use of the following formula:

The actual productivity of a group is based in part on the member characteristics of the group—the relevant traits, skills, or abilities of the individual group members. But group performance is also influenced by situational variables, such as the type of task needed to be performed. Tasks vary in terms of whether they can be divided into smaller subtasks or not, whether the group performance on the task is dependent on the abilities of the best or the worst member of the group, what specific product the group is creating, and whether there is an objectively correct decision for the task.

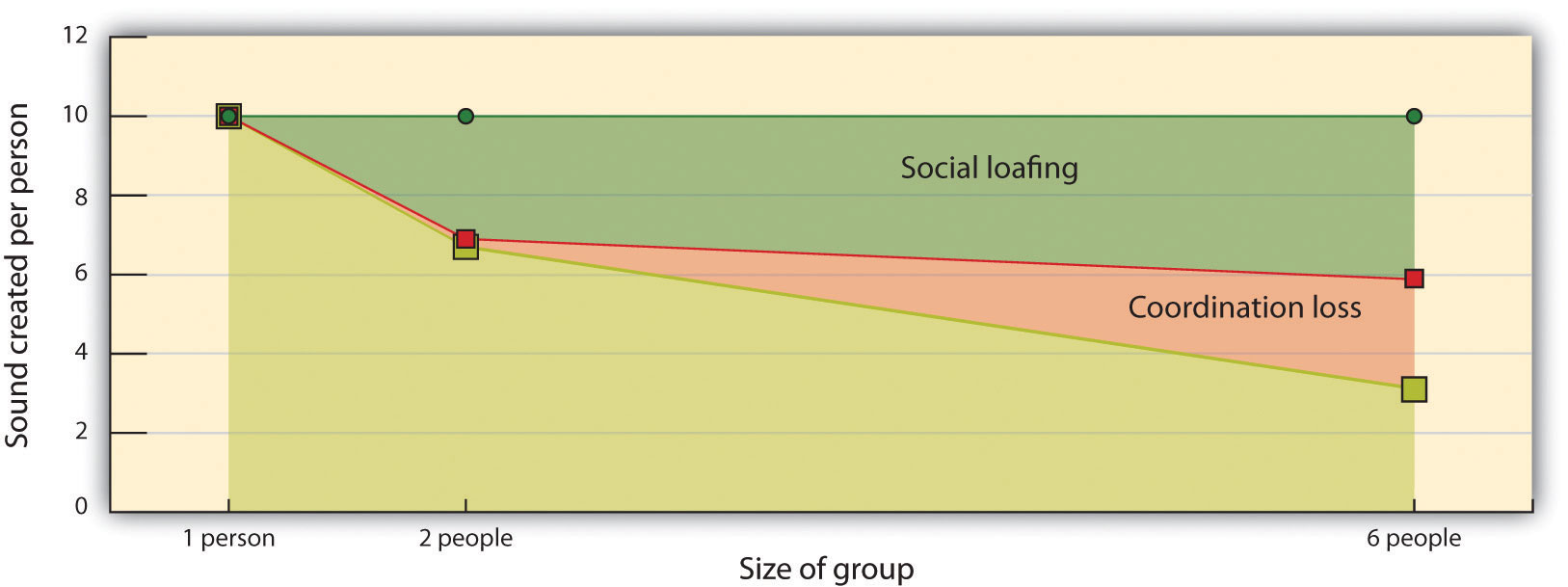

Process losses are caused by events that occur within the group that make it difficult for the group to live up to its full potential. They occur in part as a result of coordination losses that occur when people work together and in part because people do not work as hard in a group as they do when they are alone—social loafing.

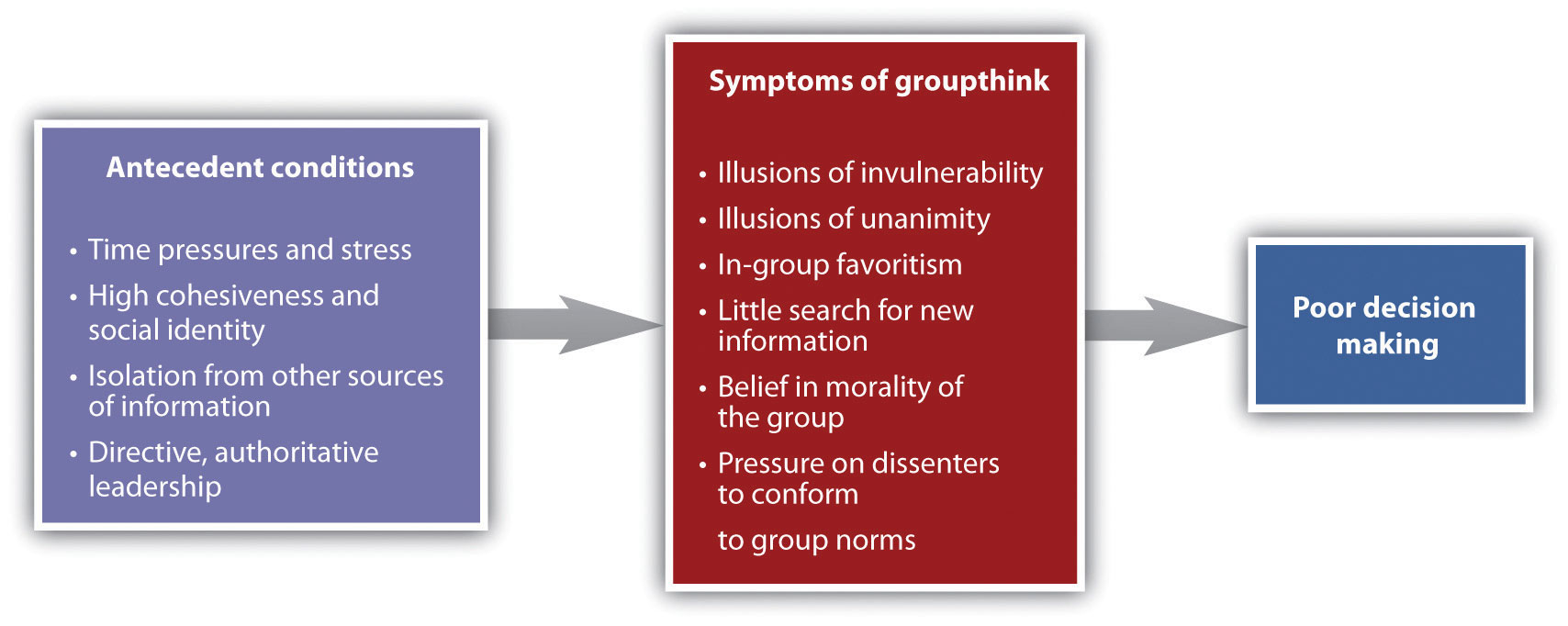

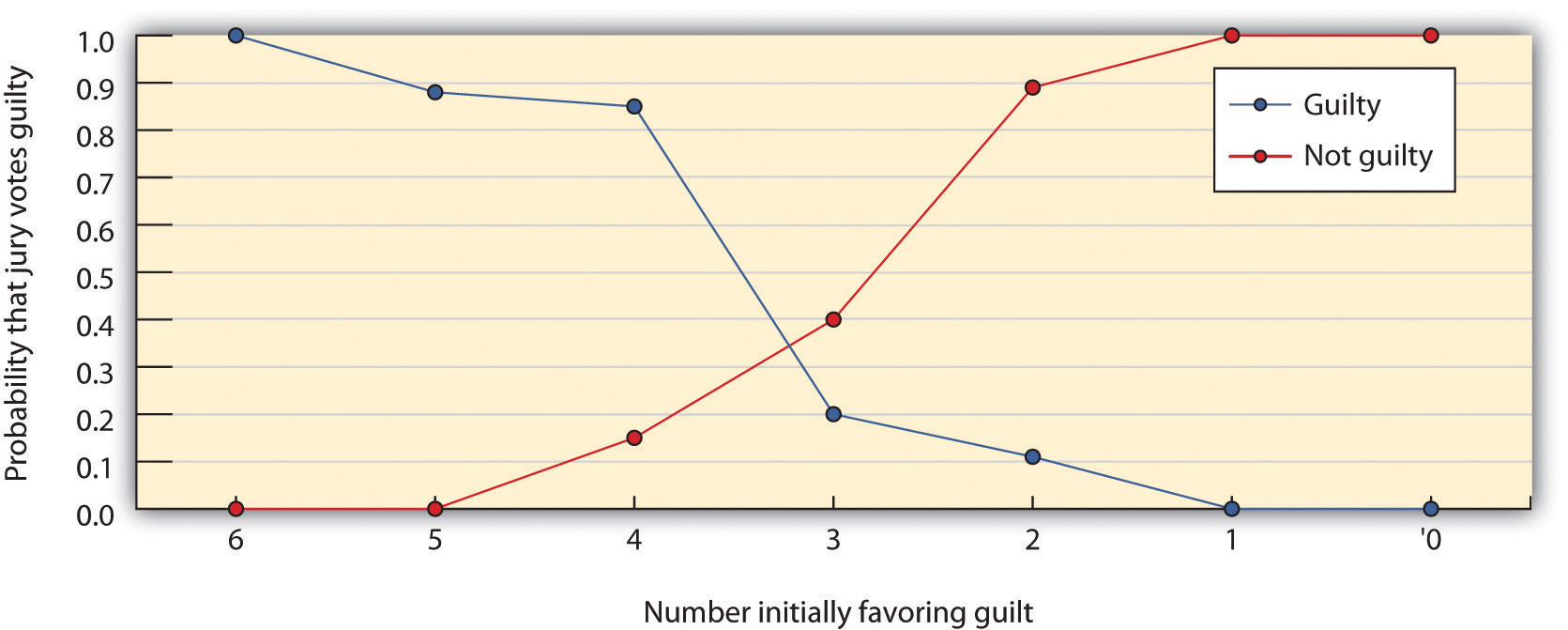

An example of a group process that can lead to very poor group decisions is groupthink. Groupthink occurs when a group, which is made up of members who may actually be very competent and thus quite capable of making excellent decisions, nevertheless ends up making a poor decision as a result of a flawed group process and strong conformity pressures. And process losses occur because group members tend to discuss information that they all have access to while ignoring equally important information that is available to only a few of the members.

One technique that is frequently used to produce creative decisions in working groups is brainstorming. However, as a result of social loafing, evaluation apprehension, and production blocking, brainstorming also creates a process loss in groups. Approaches to brainstorming that reduce production blocking, such as group support systems, can be successful.

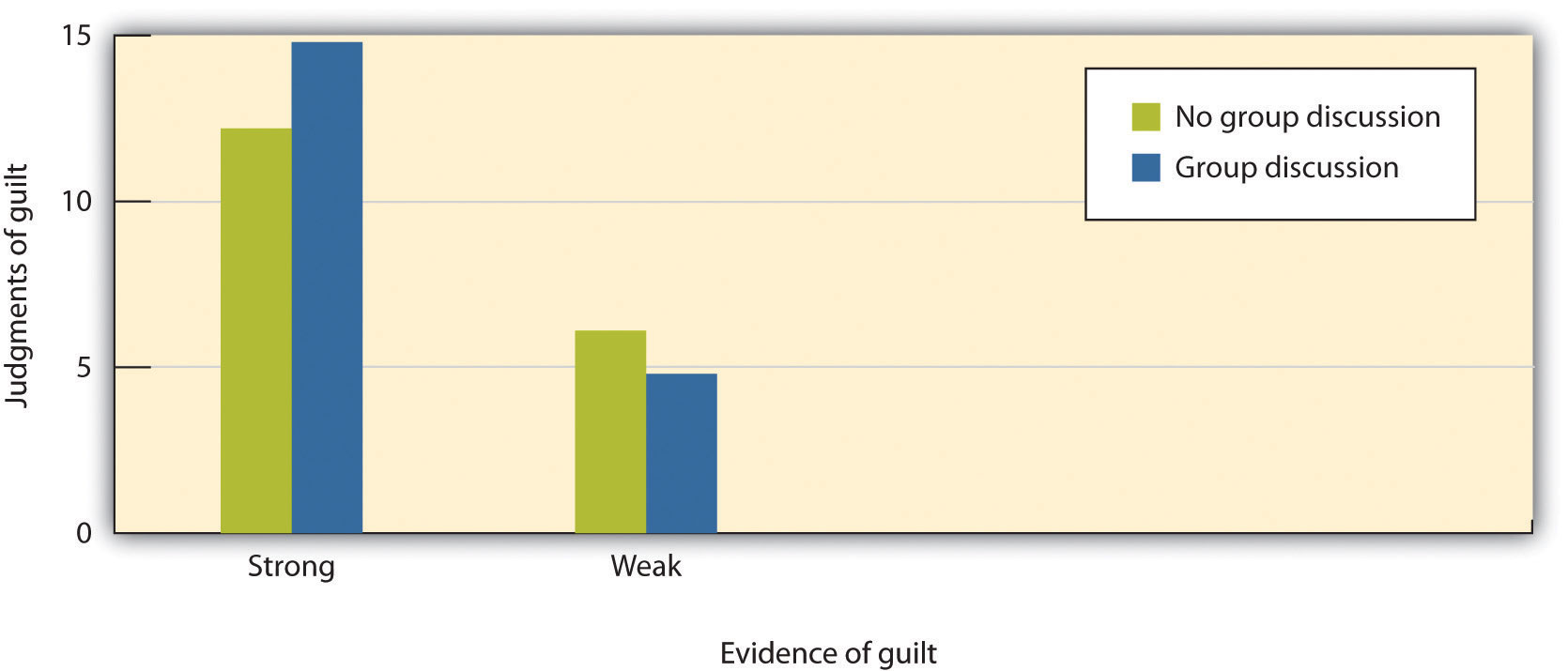

Group polarization occurs when the attitudes held by the individual group members become more extreme than they were before the group began discussing the topic. Group polarization is the result of both cognitive and affective factors.

Group members frequently overvalue the productivity of their group—the illusion of group effectivity. This occurs because the productivity of the group as a whole is highly accessible and because the group experiences high social identity. Thus groups must be motivated to work harder and to realize that their positive feelings may lead them to overestimate their worth.

Perhaps the most straightforward approach to getting people to work harder in groups is to provide rewards for performance. This approach is frequently, but not always, successful. People also work harder in groups when they feel that they are contributing to the group and that their work is visible to and valued by the other group members.

Groups are also more effective when they develop appropriate social norms—for instance, norms about sharing information. Information is more likely to be shared when the group has plenty of time to make its decision. The group leader is extremely important in fostering norms of open discussion.

One aspect of planning that has been found to be strongly related to positive group performance is the setting of goals that the group uses to guide its work. Groups that set specific, difficult and yet attainable goals perform better. In terms of group diversity, there are both pluses and minuses. Although diverse groups may have some advantages, the groups—and particularly the group leaders—must work to create a positive experience for the group members.

Your new knowledge about working groups can help you in your everyday life. When you find yourself in a working group, be sure to use this information to become a better group member and to make the groups you work in more productive.

Attribution

Adapted from Chapter 11 from Principles of Social Psychology by University of Minnesota under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.