Learning objectives

Explain the relationship between price and quantity demanded

Willingness to Pay and the Demand Curve

In general as the price of a good increases, the quantity demanded of that good decreases.

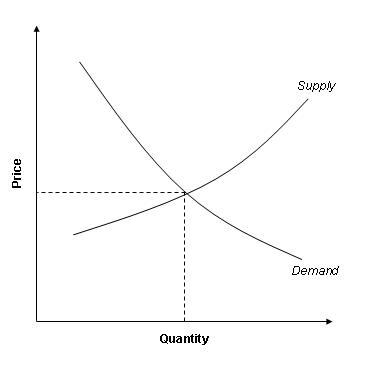

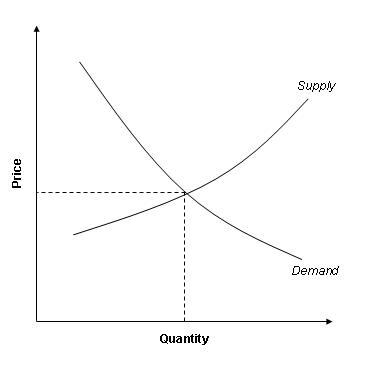

A demand curve is the graphical depiction of the relationship between the price of a certain commodity and the amount of it that consumers are willing and able to purchase at that price. Demand curves are used to estimate behaviors in competitive markets and are often used with supply curves to estimate the market equilibrium price, or the price at which sellers are willing to sell the same amount of a product as the market’s buyers are willing purchase. A demand graph can reflect the preferences of a single consumer, a group of consumers or an entire market. For demand graphs that reflect a group, the individual demands at each price are added together.

Demand is the willingness and ability of a consumer to purchase a good under the prevailing circumstances. It is defined by three elements:

- Individual Utility: An item’s utility is based on its ability to satisfy an individual’s needs or wants. Some utility is universal; every human needs water to survive so it has high utility for everyone. Some utility is based on personal preference; some people prefer Coke over Pepsi so for them Coke has the higher utility. The more people that find utility in the good the greater the market demand; the greater the individual utility in the product the greater the individual demand.

- Purchasing Power: Demand is measured based on a person’s willingness to buy under the prevailing circumstances. If an individual lacks the money to purchase the product, she can’t demand it because she cannot afford it.

- Ability to Decide: The individual must be able to choose to make a purchase. Sometimes circumstances may prevent a person from purchasing something they might desire, even if they have the necessary money. For example, an underaged person may not be permitted by law to purchase cigarettes. That person might want the cigarettes and can afford to purchase them, but since it is against the law for him to purchase it, there is no demand.

For the vast majority of goods and services, an increase in price will lead to a decrease in the quantity demanded. There are two exceptions to this general rule.

Supply and demand graph: The downward sloping demand curve reflects the fact that as price increases, consumers willing to purchase less of the good or service.

Veblen Goods

Veblen goods are expensive luxury products, such as designer handbags and high-end cars. In these rare circumstances, decreasing the price actually decreases the demand for the good. The reason for this is because part of the value of the good is exclusivity. These items are status symbols and lowering the price diminishes the status.

Giffen Goods

Giffen goods are another example where rising prices can lead to increased demand for a product. Giffen goods are very rare and are defined by three characteristics:

- It is an inferior good, or a good for which demand decreases as consumer income rises,

- There must be a lack of substitute product,

- The good must constitute a substantial percentage of the buyer’s income, but not such a substantial percentage of the buyer’s income that none of the associated normal goods are consumed.

For example, imagine a significant portion of a family’s grocery bill is bread. Bread is a staple and it is the cheapest option out of the food available. If bread prices rise, the family will need to cut back on other groceries to make up the difference. However, since the family still need to eat a certain amount of calories each day and bread is still the cheapest option, they will purchase more bread to make up for the food they aren’t purchasing and consuming. In this instance, bread is a giffen good.

The Demand Curve and Consumer Surplus

Consumer surplus is the difference between the maximum price a consumer is willing to pay and the actual price they do pay.

Learning objectives

Illustrate consumer surplus with the demand schedule and demand curve

Consumer surplus is the difference between the maximum price a consumer is willing to pay and the actual price they do pay. If a consumer would be willing to pay more than the current asking price, then they are getting more benefit from the purchased product than they spent to buy it. Consumer surplus plus producer surplus equals the total economic surplus in the market.

This chart graphically illustrates consumer surplus in a market without any monopolies, binding price controls, or any other inefficiencies. The price in this chart is set at the pareto optimal. This means that the price could not be increased or decreased without one of the parties being made worse off. The consumer surplus, as marked in red, is bound by the y-axis on the left, the demand curve on the right, and a horizontal line where y equals the equilibrium price. This area represent the amount of goods consumers would have been willing to purchase at a price higher than the pareto optimal price. Generally, the lower the price, the greater the consumer surplus.

Consumer Surplus: Consumer surplus, as shown highlighted in red, represents the benefit consumers get for purchasing goods at a price lower than the maximum they are willing to pay.

Another way to define consumer surplus in less quantitative terms is as a measure of a consumer’s well-being. Some goods, like water, are valuable to everyone because it is a necessity for survival. But the utility, or “usefulness,” of most goods vary depending on a person’s individual preferences. Since the utility a person gets from a good defines her demand for it, utility also defines the consumer surplus an individual might get from purchasing that item. If a person has no use for a good, there is no consumer’s surplus for that person in purchasing the good no matter the price. However, if a person finds a good incredibly useful, consumer surplus will be significant even if the price is high. An individual’s customer surplus for a product is based on the individual’s utility of that product.

Impacts of Price Changes on Consumer Surplus

Consumer surplus decreases when price is set above the equilibrium price, but increases to a certain point when price is below the equilibrium price.

Learning objectives

Explain how shifting a price away from pareto optimal will impact consumer surplus

Consumer surplus is defined, in part, by the price of the product. Recall that the consumer surplus is calculating the area between the demand curve and the price line for the quantity of goods sold. Assuming that there is no shift in demand, an increase in price will therefore lead to a reduction in consumer surplus, while a decrease in price will lead to an increase in consumer surplus.

Consumer Surplus: An increase in the price will reduce consumer surplus, while a decrease in the price will increase consumer surplus.

Below are two scenarios that illustrate how changes in price can affect consumers’ surplus. It is important to note that any shift from the good’s pareto optimal price will result in a decrease in the total economic surplus. The total economic surplus equals the sum of the consumer and producer surpluses.

Price Ceiling

A binding price ceiling is one that is lower than the pareto efficient market price. This means that consumers will be able to purchase the product at a lower price than what would normally be available to them. It might appear that this would increase consumer surplus, but that is not necessarily the case.

For consumers to achieve a surplus they have to be able to purchase the product, which means that producers have to make enough to be purchased at a price. If a good’s price drops below the market equilibrium for whatever reason, manufacturing the product will be less profitable for the producers. So while more consumers will want to purchase the product because of its low price, they will not be able to. This means the market will have a shortage for that good. This shortage will create a deadweight loss, or a market wide loss of efficiency and value that neither producer nor consumers obtain.

So any increase in consumer surplus due to the decrease in price may be offset by the fact that consumers that want the good cannot purchase it. At some point the benefit from the drop in price will be outweighed by the decrease in the good’s availability.

Price Floor

When a price floor is set above the equilibrium price, consumers will have to purchase the product at a higher price. Therefore, fewer consumers will purchase the product because some will decide that the utility they get from the good is not worth the price. Necessarily, this reflects a drop in consumer surplus.

Key Points

- Demand is the willingness and ability of a consumer to purchase a good under certain circumstances.

- Demand curves are used to estimate behaviors in competitive markets and are often used with supply curves to estimate the market equilibrium price, or the price at which sellers are willing to sell the same amount of a product as the market’s buyers are willing purchase.

- An individual’s demand is defined by her utility, purchasing power, and ability to make a purchasing decision.

- On a supply and demand chart, consumer surplus is bound by the y-axis on the left, the demand curve on the right, and a horizontal line where y equals the current market price.

- Another way to define consumer surplus in less quantitative terms is as a measure of a consumer’s well-being.

- An individual’s customer surplus for a product is based on the individual’s utility of that product.

- Consumer surplus will only increase as long as the benefit from the lower price exceeds the costs from the resulting shortage.

- Consumer surplus always decreases when a binding price floor is instituted in a market above the equilibrium price.

- The total economic surplus equals the sum of the consumer and producer surpluses.

- Price helps define consumer surplus, but overall surplus is maximized when the price is pareto optimal, or at equilibrium.

Key Terms

- demand curve: The graph depicting the relationship between the price of a certain commodity and the amount of it that consumers are willing and able to purchase at that given price.

- utility: The ability of a commodity to satisfy needs or wants; the satisfaction experienced by the consumer of that commodity.

- consumer surplus: The difference between the maximum price a consumer is willing to pay and the actual price they do pay.

- price floor: A mandated minimum price for a product in a market.

- Price ceiling: A government-imposed price control or limit on how high a price is charged for a product.

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SPECIFIC ATTRIBUTION

- Inferior good. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Inferior_good. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Giffen good. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Giffen_good. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Veblen good. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Veblen_good. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Microeconomics/Supply and Demand. Provided by: Wikibooks. Located at: en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Microeconomics/Supply_and_Demand%23Demand_Curve. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Demand curve. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Demand_curve. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless. Provided by: Boundless Learning. Located at: www.boundless.com//marketing/definition/demand-curve. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- utility. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/utility. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Why is Music Cheaper Now?nIt's as Simple as Supply andu00a0Demand - MTT - Music Think Tank. Provided by: Music Think Tank. Located at: http://www.musicthinktank.com/blog/why-is-music-cheaper-now-its-as-simple-as-supply-and-demand.html. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Principles of Economics/Demand. Provided by: Wikibooks. Located at: en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Principles_of_Economics/Demand%23Consumer_surplus. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Utility. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Utility. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Consumer's surplus. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Consumer's_surplus%23Consumer_surplus. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- consumer surplus. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/consumer%20surplus. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Why is Music Cheaper Now?nIt's as Simple as Supply andu00a0Demand - MTT - Music Think Tank. Provided by: Music Think Tank. Located at: http://www.musicthinktank.com/blog/why-is-music-cheaper-now-its-as-simple-as-supply-and-demand.html. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Economic-surpluses. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Economic-surpluses.svg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Principles of Economics/Demand. Provided by: Wikibooks. Located at: en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Principles_of_Economics/Demand%23Consumer_surplus. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Consumer's surplus. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Consumer's_surplus%23Consumer_surplus. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Deadweight loss. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Deadweight_loss. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless. Provided by: Boundless Learning. Located at: www.boundless.com//economics/...on/price-floor. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless. Provided by: Boundless Learning. Located at: www.boundless.com//economics/.../price-ceiling. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Why is Music Cheaper Now?nIt's as Simple as Supply andu00a0Demand - MTT - Music Think Tank. Provided by: Music Think Tank. Located at: http://www.musicthinktank.com/blog/why-is-music-cheaper-now-its-as-simple-as-supply-and-demand.html. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Economic-surpluses. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Economic-surpluses.svg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- All sizes | consumer-surplus-is-the-differnece-between-what-you-are-prepared-to-pay-and-what-you-end-up-paying | Flickr - Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: http://www.flickr.com/photos/8066664...n/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution