1.4: College Culture and Expectations

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 207299

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Questions to consider

- What language and customs do you need to know to succeed in college?

- What is your responsibility for learning in college?

- What resources will you use to meet these expectations?

- What are the common challenges in the first year?

College Has Its Own Language and Customs

Going to college—even if you are not far from home—is a cultural experience. It comes with its own language and customs, some of which can be confusing or confounding at first. Just like traveling to a foreign country, it is best if you prepare by learning what words mean and what you are expected to say and do in certain situations.

Let’s first start with the language you may encounter. In most cases, there will be words that you have heard before, but they may have different meanings in a college setting. Take, for instance, “office hours.” If you are not in college, you would think that it means the hours of a day that an office is open. If it is your dentist’s office, it may mean Monday through Friday from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. In college, “office hours” can refer to the specific hours a professor is in her office to meet with students, and those hours may be only a few each day: for example, Mondays and Wednesdays from 1 p.m. until 3 p.m.

“Syllabus” is another word that you may not have encountered, but it is one you will soon know very well. A syllabus is often called the “contract of the course” because it contains information about what to expect—from the professor and the student. It is meant to be a roadmap for succeeding in the class. Understanding that office hours are for you to ask your professor questions and the syllabus is the guide for what you will be doing in the class can make a big difference in your transition to college. The table on Common College Terms, has a brief list of other words that you will want to know when you hear them on campus.

| Term | What It Means | Why You Need to Know |

|---|---|---|

| Attendance policy | A policy that describes the attendance and absence expectations for a class | Professors will have different attendance expectations. Read your syllabus to determine which ones penalize you if you miss too many classes. |

| Final exam | A comprehensive assessment that is given at the end of a term | If your class has a final exam, you will want to prepare for it well in advance by reading assigned material, taking good notes, reviewing previous tests and assignments, and studying. |

| Learning | The process of acquiring knowledge | In college, most learning happens outside the classroom. Your professor will only cover the main ideas or the most challenging material in class. The rest of the learning will happen on your own. |

| Office hours | Specific hours professor is in the office to meet with students | Visiting your professor during office hours is a good way to get questions answered and to build rapport. |

| Plagiarism | Using someone’s words, images, or ideas as your own, without proper attribution | Plagiarism carries much more serious consequences in college, so it is best to speak to your professor about how to avoid it and review your student handbook’s policy. |

| Study | The process of using learning strategies to understand and recall information | Studying in college may look different than studying in high school in that it may take more effort and more time to learn more complex material. |

| Syllabus | The contract of a course that provides information about course expectations and policies | The syllabus will provide valuable information that your professor will assume you have read and understood. Refer to it first when you have a question about the course. |

Activity

The language that colleges and universities use can feel familiar but mean something different, as you learned in the section above, and it can also seem alien, especially when institutions use acronyms or abbreviations for buildings, offices, and locations on campus. Terms such as “quad” or “union” can denote a location or space for students. Then there may be terms such as “TLC” (The Learning Center, in this example) that designate a specific building or office. Describe a few of the new terms you have encountered so far and what they mean. If you are not sure, ask your professor or a fellow student to define it for you.

In addition to its own language, higher education has its own way of doing things. For example, you may be familiar with what a teacher did when you were in high school, but do you know what a professor does? It certainly seems like they fulfill a very similar role as teachers in high school, but in college professors’ roles are often much more diverse. In addition to teaching, they may also conduct research, mentor graduate students, write and review research articles, serve on and lead campus committees, serve in regional and national organizations in their disciplines, apply for and administer grants, advise students in their major, and serve as sponsors for student organizations. You can be assured that their days are far from routine. See the Table on Differences between High School Teachers and College Professors for just a few differences between high school teachers and college professors.

| High School Faculty | College Faculty |

|---|---|

| Often have degrees or certifications in teaching in addition to degrees in subject matter | Most likely have not even taken a course in teaching as part of their graduate program |

| Responsibilities include maximizing student learning and progress in a wide array of areas | Responsibilities include providing students with content and an assessment of their mastery of the content |

| Are available before or after school or during class if a student has a question | Are available during office hours or by appointment if a student needs additional instruction or advice |

| Communicate regularly and welcome questions from parents and families about a student’s progress | Cannot communicate with parents and families of students without permission because of the Federal Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) |

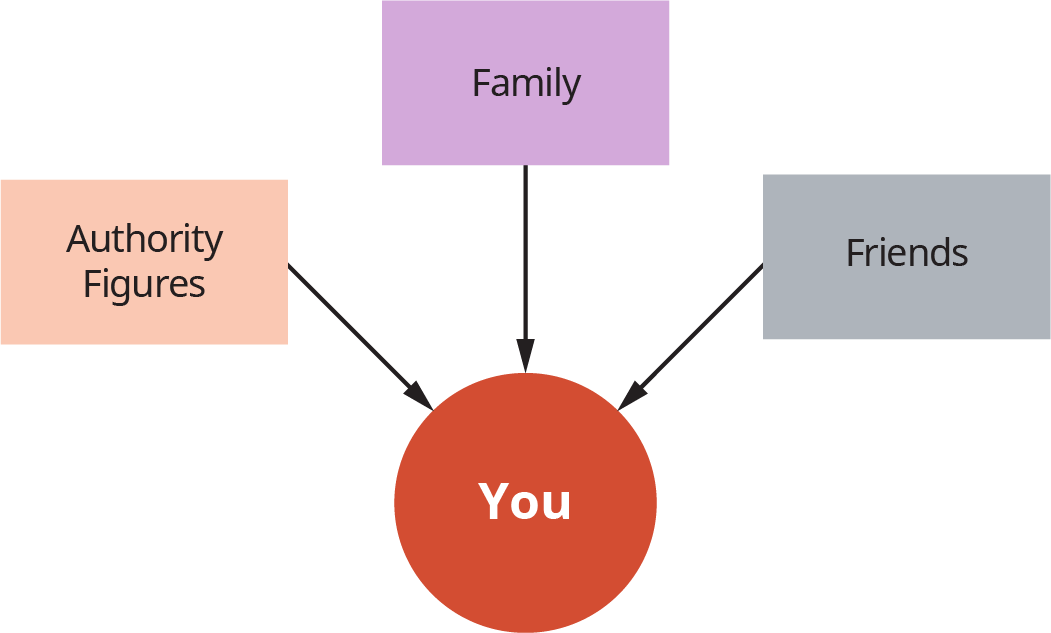

The relationships you build with your professors will be some of the most important ones you create during your college career. You will rely on them to help you find internships, write letters of recommendation, nominate you for honors or awards, and serve as references for jobs. You can develop those relationships by participating in class, visiting during office hours, asking for assistance with coursework, requesting recommendations for courses and majors, and getting to know the professor’s own academic interests. One way to think about the change in how your professors will relate to you is to think about the nature of relationships you have had growing up. In Figure 1.8: You and Your Relationships Before College you will see a representation of what your relationships probably looked like. Your family may have been the greatest influencer on you and your development.

"The relationships you build with your professors will be some of the most important ones during your college career."

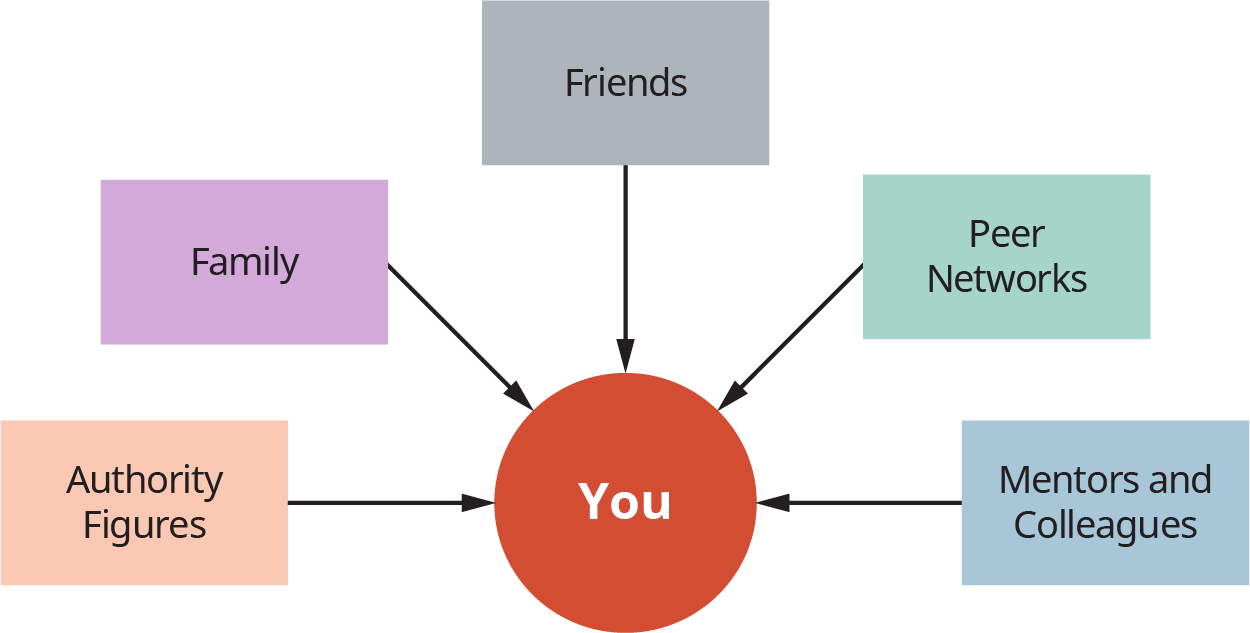

In college, your networks are going to expand in ways that will help you develop other aspects of yourself. As described above, the relationships you will have with your professors will be some of the most important. But they won’t be the only relationships you will be cultivating while in college. Consider the Figure on You and Your Relationships during College and think about how you will go about expanding your network while you are completing your degree.

Your relationships with authority figures, family, and friends may change while you are in college, and at the very least, your relationships will expand to peer networks—not friends, but near-age peers or situational peers (e.g., a first-year college student who is going back to school after being out for 20 years)—and to faculty and staff who may work alongside you, mentor you, or supervise your studies. These relationships are important because they will allow you to expand your network, especially as it relates to your career. As stated earlier, developing relationships with faculty can provide you with more than just the benefits of a mentor. Faculty often review applications for on-campus jobs or university scholarships and awards; they also have connections with graduate programs, companies, and organizations. They may recommend you to colleagues or former classmates for internships and even jobs.

Other differences between high school and college are included in the table about Differences between High School and College. Because it is not an exhaustive list of the differences, be mindful of other differences you may notice. Also, if your most recent experience has been the world of work or the military, you may find that there are more noticeable differences between those experiences and college.

| High School | College | Why You Need to Know the Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Grades |

Grades are made up of frequent tests and homework, and you may be able to bring up a low initial grade by completing smaller assignments and bonuses. | Grades are often made up of fewer assignments, and initial low grades may keep you from earning high course grades at the end of the semester. | You will need to be prepared to earn high grades on all assignments because you may not have the opportunity to make up for lost ground. |

|

Learning |

Learning is often done in class with the teacher guiding the process, offering multiple ways to learn material and frequent quizzes to ensure that learning is occurring. | Learning happens mostly outside of class and on your own. Faculty are responsible for assigning material and covering the most essential ideas; you are responsible for tracking and monitoring your learning progress. | You will need to practice effective learning strategies on your own to ensure that you are mastering material at the appropriate pace. |

|

Getting Help |

Your teachers, parents, and a counselor are responsible for identifying your need for help and for creating a plan for you to get help with coursework if you need it. Extra assistance is usually reserved for students who have an official diagnosis or need. | You will most likely need help to complete all your courses successfully even if you did not need extra help in high school. You will be responsible for identifying that you need it, accessing the resources, and using them. | Because the responsibility is on you, not parents or teachers, to get the help you need, you will want to be aware of when you may be struggling to learn material. You then will need to know where the support can be accessed on campus or where you can access support online. |

|

Tests and Exams |

Tests cover small amounts of material and study days or study guides are common to help you focus on what you need to study. If you paid attention in class, you should be able to answer all the questions. | Tests are fewer and cover more material than in high school. If you read all the assigned material, took good notes in class, and spent time practicing effective study techniques, you should be able to answer all the questions. | This change in how much material and the depth of which you need to know the material is a shock for some students. This may mean you need to change your strategies dramatically to get the same results. |

Some of What You Will Learn Is “Hidden”

Many of the college expectations that have been outlined so far may not be considered common knowledge, which is one reason that so many colleges and universities have classes that help students learn what they need to know to succeed. The term, which was coined by sociologists,7 describes unspoken, unwritten, or unacknowledged (hence, hidden) rules that students are expected to follow that can affect their learning. To illustrate the concept, consider the situation in the following activity.

Activity

Situation: Your history syllabus indicates that, on Tuesday, your professor is lecturing on the chapter that covers the stock market crash of 1929.

This information sounds pretty straightforward. Your professor lectures on a topic and you will be there to hear it. However, there are some unwritten rules, or hidden curriculum, that are not likely to be communicated. Can you guess what they may be? Take a moment to write at least one potential unwritten rule.

- What is an unwritten rule about what you should be doing before attending class?

_______________________________________________________________ - What is an unwritten rule about what you should be doing in class?

_______________________________________________________________ - What is an unwritten rule about what you should be doing after class?

_______________________________________________________________ - What is an unwritten rule if you are not able to attend that class?

_______________________________________________________________

Some of your answers could have included the following:

Before class: Read the assigned chapter, take notes, record any questions you have about the reading.

During class: Take detailed notes, ask critical thinking or clarifying questions, avoid distractions, bring your book and your reading notes.

After class: Reorganize your notes in relation to your other notes, start the studying process by testing yourself on the material, make an appointment with your professor if you are not clear on a concept.

Absent: Communicate with the professor, get notes from a classmate, make sure you did not miss anything important in your notes.

The expectations before, during, and after class, as well as what you should do if you miss class, are often unspoken because many professors assume you already know and do these things or because they feel you should figure them out on your own. Nonetheless, some students struggle at first because they don’t know about these habits, behaviors, and strategies. But once they learn them, they are able to meet them with ease.

Learning Is Your Responsibility

As you may now realize by reviewing the differences between high school and college, learning in college is your responsibility. Before you read about the how and why of being responsible for your own learning, complete the Activity below.

Activity

For each statement, circle the number that best represents you, with 1 indicating that the statement is least like you, and 5 indicating that the statement is most like you.

| Most of the time, I can motivate myself to complete tasks even if they are boring or challenging. | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I regularly work hard when I need to complete a task no matter how small or big the task may be. | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I use different strategies to manage my time effectively and minimize procrastination to complete tasks. | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I regularly track my progress completing work and the quality of work I do produce. | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I believe how much I learn and how well I learn is my responsibility. | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Were you able to mark mostly 4s and 5s? If you were even able to mark at least one 4 or 5, then you are well on your way to taking responsibility for your own learning. Let’s break down each statement in the components of the ownership of learning:

- Motivation. Being able to stay motivated while studying and balancing all you have to do in your classes will be important for meeting the rest of the components.

- Deliberate, focused effort. Taking ownership of learning will hinge on the effort that you put into the work. Because most learning in college will take place outside of the classroom, you will need determination to get the work done. And there will be times that the work will be challenging and maybe even boring, but finding a way to get through it when it is not exciting will pay in the long run.

- Time and task management. You will learn more about strategies for managing your time and the tasks of college in a later chapter, but without the ability to control your calendar, it will be difficult to block out the time to study.

- Progress tracking. A commitment to learning must include monitoring your learning, knowing not only what you have completed (this is where a good time management strategy can help you track your tasks), but also the quality of the work you have done.

Taking responsibility for your learning will take some time if you are not used to being in the driver’s seat. However, if you have any difficulty making this adjustment, you can and should reach out for help along the way.

What to Expect During the First Year

While you may not experience every transition within your first year, there are rhythms to each semester of the first year and each year you are in college. Knowing what to expect each month or week can better prepare you to take advantage of the times that you have more confidence and weather through the times that seem challenging. Review the table on First-Year College Student Milestones. There will be milestones each semester you are in college, but these will serve as an introduction to what you should expect in terms of the rhythms of the semester.

|

First-Year College Student Milestones for the First Semester |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| August | September | October | November | December |

| Expanding social circles | Completing first test and projects | Feeling more confident about abilities | Balancing college with other obligations | Focusing on finishing strong |

| Experiencing homesickness or imposter syndrome | Earning “lower-than-usual” grades or not meeting personal expectations | Dealing with relationship issues | Staying healthy and reducing stress | Handling additional stress of the end of the semester |

| Adjusting to the pace of college | Learning to access resources for support | Planning for next semester and beyond | Thinking about majors and degrees | Thinking about the break and how to manage changes |

The first few weeks will be pretty exhilarating. You will meet new people, including classmates, college staff, and professors. You may also be living in a different environment, which may mean that a roommate is another new person to get to know. Overall, you will most likely feel both excited and nervous. You can be assured that even if the beginning of the semester goes smoothly, your classes will get more challenging each week. You will be making friends, learning who in your classes seem to know what is going on, and figuring your way around campus. You may even walk into the wrong building, go to the wrong class, or have trouble finding what you need during this time. But those first-week jitters will end soon. Students who are living away from home for the first time can feel homesick in the first few weeks, and others can feel what is called “imposter syndrome,” which is a fear some students have that they don’t belong in college because they don’t have the necessary skills for success. Those first few weeks sound pretty stressful, but the stress is temporary.

After the newness of college wears off, reality will set in. You may find that the courses and assignments do not seem much different than they did in high school (more on that later), but you may be in for a shock when you get your graded tests and papers. Many new college students find that their first grades are lower than they expected. For some students, this may mean they have earned a B when they are used to earning As, but for many students, it means they may experience their first failing or almost-failing grades in college because they have not used active, effective study strategies; instead, they studied how they did in high school, which is often insufficient. This can be a shock if you are not prepared, but it doesn’t have to devastate you if you are willing to use it as a wake-up call to do something different.

By the middle of the semester, you’ll likely feel much more confident and a little more relaxed. Your grades are improving because you started going to tutoring and using better study strategies. You are looking ahead, even beyond the first semester, to start planning your courses for the next term. If you are working while in college, you may also find that you have a rhythm down for balancing it all; additionally, your time management skills have likely improved.

By the last few weeks of the semester, you will be focused on the increasing importance of your assignments and upcoming finals and trying to figure out how to juggle that with the family obligations of the impending holidays. You may feel a little more pressure to prepare for finals, as this time is often viewed as the most stressful period of the semester. All of this additional workload and need to plan for the next semester can seem overwhelming, but if you plan ahead and use what you learn from this chapter and the rest of the course, you will be able to get through it more easily.

Don’t Do It Alone

Think about our earlier descriptions of two students, Reginald and Madison. What if they found that the first few weeks were a little harder than they had anticipated? Should they have given up and dropped out? Or should they have talked to someone about their struggles? Here is a secret about college success that not many people know: successful students seek help. They use resources. And they do that as often as necessary to get what they need. Your professors and advisors will expect the same from you, and your college will have all kinds of offices, staff, and programs that are designed to help. This bears calling out again: you need to use those resources. These are called “help-seeking behaviors,” and along with self-advocacy, which is speaking up for your needs, they are essential to your success. As you get more comfortable adjusting to life in college, you will find that asking for help is easier. In fact, you may become really good at it by the time you graduate, just in time for you to ask for help finding a job! Review the table on Issues, Campus Resources, and Potential Outcomes for a few examples of times you may need to ask for help. See if you can identify where on campus you can find the same or a similar resource.

|

Issues, Campus Resources, and Potential Outcomes |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Issue | Campus Resource | Potential Outcome |

| Academic | You are struggling to master the homework in your math class. | The campus tutoring center | A peer or professional tutor can walk you through the steps until you can do them on your own. |

| Health | You have felt extremely tired over the past two days and now you have a cough. | The campus health center | A licensed professional can examine you and provide care. |

| Social | You haven’t found a group to belong to. Your classmates seem to be going in different directions and your roommate has different interests. | Student organizations and interest groups | Becoming a member of a group on campus can help you make new friends. |

| Financial | Your scholarship and student loan no longer cover your college expenses. You are not sure how to afford next semester. | Financial aid office | A financial aid counselor can provide you with information about your options for meeting your college expenses. |

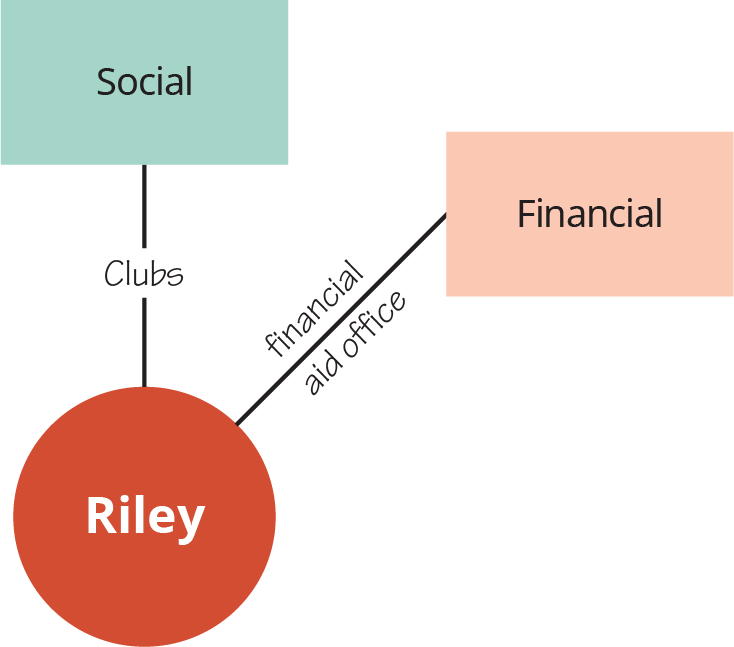

Application

Using a blank sheet of paper, write your name in the center of the page and circle it. Then, draw six lines from the center (see example in the figure below) and label each for the six areas of adjustment that were discussed earlier. Identify a campus resource or strategy for making a smooth adjustment for each area.

Common Challenges in the First Year

It seems fitting to follow up the expectations for the first year with a list of common challenges that college students encounter along the way to a degree. If you experience any—or even all—of these, the important point here is that you are not alone and that you can overcome them by using your resources. Many college students have felt like this before, and they have survived—even thrived—despite them because they were able to identify a strategy or resource that they could use to help themselves. At some point in your academic career, you may do one or more of the following:

- Feel like an imposter. There is actually a name for this condition: imposter syndrome. Students who feel like an imposter are worried that they don’t belong, that someone will “expose them for being a fake.” This feeling is pretty common for anyone who finds themselves in a new environment and is not sure if they have what it takes to succeed. Trust the professionals who work with first-year college students: you do have what it takes, and you will succeed. Just give yourself time to get adjusted to everything.

- Worry about making a mistake. This concern often goes with imposter syndrome. Students who worry about making a mistake don’t like to answer questions in class, volunteer for a challenging assignment, and even ask for help from others. Instead of avoiding situations where you may fail, embrace the process of learning, which includes—is even dependent on—making mistakes. The more you practice courage in these situations and focus on what you are going to learn from failing, the more confident you become about your abilities.

- Try to manage everything yourself. Even superheroes need help from sidekicks and mere mortals. Trying to handle everything on your own every time an issue arises is a recipe for getting stressed out. There will be times when you are overwhelmed by all you have to do. This is when you will need to ask for and allow others to help you.

- Ignore your mental and physical health needs. If you feel you are on an emotional rollercoaster and you cannot find time to take care of yourself, then you have most likely ignored some part of your mental and physical well-being. What you need to do to stay healthy should be non-negotiable. In other words, your sleep, eating habits, exercise, and stress-reducing activities should be your highest priorities.

- Forget to enjoy the experience. Whether you are 18 years old and living on campus or 48 years old starting back to college after taking a break to work and raise a family, be sure to take the time to remind yourself of the joy that learning can bring.

Get Connected

Which apps help you meet the expectations of college? Will you be able to meet the expectations of being responsible for your schedule and assignments?

- My Study Life understands how college works and provides you with a calendar, to-do list, and reminders that will help you keep track of the work you have to do.

How can you set goals and work toward them while in college?

- The Strides app provides you with the opportunity to create SMART (Specific, Measureable, Attainable, Relevant, and Time bound) goals and track daily habits. These daily habits will add up over time toward your goals.

What can you do to develop your learning skills?

- Lumosity is a brain-training app that can help you build the thinking and learning skills you will need to meet learning challenges in college. If you want to test your memory and attention—and build your skills—take the fit test and then play different games to improve your fitness.

How can you develop networks with people in college?

- LinkedIn is a professional networking app that allows you to create a profile and network with others. Creating a LinkedIn account as a first-year college student will help you create a professional profile that you can use to find others with similar interests.

- Internships.com provides information, connections, and support to help your career planning and activities. Even if you are not planning an internship right away, you may find some useful and surprising ideas and strategies to motivate your approach.

Footnotes

- P.P. Bilbao, P. I. Lucido, T. C. Iringan and R. B. Javier. (2008). Curriculum Development.