2.2: Culture Shock

- Page ID

- 224559

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Define culture shock and its key components (affective, behavioral, and cognitive).

- Identify Factors that influence culture shock.

- Distinguish between travelers and tourists, and their respective approaches to cultural experiences.

- Recognize the role of host culture attitudes in shaping the visitor's experience.

Introduction to Culture Shock

In the previous chapter, we explored the topics of cultural adaptation and acculturation. In this chapter, we will explore further the concept of cultural adaptation through the framework of cultural shock. As we know, understanding intercultural communication is not the same thing as experiencing it. To experience intercultural communication, one needs to get off the couch and set foot into a new and unfamiliar culture. When a person moves from a familiar cultural environment to one that is different than their own, they often experience personal disorientation called culture shock. Culture shock refers to the anxiety and discomfort we feel when moving from a familiar environment to an unfamiliar one. In our own culture, through time, we have learned the million and one ways how to communicate appropriately with friends, family members, colleagues, and others. We know how to great people, when and how to give tips, whether to stand or sit, how much eye contact to make, when to accept and refuse invitations, how to understand directions, whether others are being sarcastic or not, how holidays are and are not celebrated, how to shop for and prepare food, and generally how to communicate verbally and nonverbally in any given social situation. When we enter a new culture, many of those familiar signs and signals are gone, leading us to feel helplessly lost in many circumstances.

The ABCs of Culture Shock

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, culture shock is “a sense of confusion and uncertainty sometimes with feelings of anxiety that may affect people exposed to an alien culture or environment without adequate preparation”. Culture shock is first and foremost an emotional response to a change in our cultural environment. But it also impacts how we act and how we think. The ABCs of culture shock refer to the affective, behavioral, and cognitive changes brought on by culture shock. The affective dimension of culture shock refers to the anxiety, bewilderment, and disorientation of experiencing a new culture. Kalervo Oberg (1960) believed culture shock produced an identity loss and confusion from the psychological toll exerted to adjust to a new culture. The behavioral dimension refers to confusion over behaviors of people in the host culture. We don't understand why people are behaving they way they are in certain situations and we are not sure how to act appropriately. The cognitive dimension refers to our inability to interpret our new environment or understand these "bizarre" social experiences.

Underlying Factors

Over the past several decades, there have been numerous peer-reviewed, scholarly studies documenting the effects of culture shock. The research suggests that nearly everybody who enters a new culture will experience some form of culture shock, but not everybody experiences culture shock the same way. How long culture shock lasts and the degree to which it is felt will vary according to several underlying factors. One of the most important factors is motivational orientation. Some people travel willingly and are excited to enter a new culture. Students who decide to study abroad, travelers who want to explore the world, and families who go on vacations provide a few examples. These groups generally have a high motivational orientation and generally have an easier time adapting to culture shock. By contrast, others enter a new culture reluctantly or unwillingly. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), there are 70.8 million forcibly displaced people worldwide. These include refugees, asylum-seekers, and internally displaced people. To put that number in perspective, that is 1 out of every one hundred people on the planet. This is the highest number in human history and it is only expected to grow as war and conflicts continue, and catastrophic climate change threatens to make many parts of the world uninhabitable in the near future. These people generally have a low motivational orientation as they do not want to leave their home cultures but do so because their very survival depends on it.

When the author of this chapter was in graduate school in San Francisco, he took a semester off and traveled for 4 months through several Asian countries. On that trip, he met a German woman while on a boat from Sumatra to Malaysia. They traveled together up to Thailand before parting ways. Months later, she came to visit and later moved into his apartment in San Francisco. Eventually, they married, and have been together ever since. But back in those days in San Francisco, they had a roommate who saw our relationship develop firsthand. He wasn't having much luck with the dating scene in San Francisco and decided that he, too, would like to meet a "European girl." So he set off for a month to Thailand and India, hoping he would find "the girl of is dreams." This anecdote speaks to another underlying factor, personal expectations. People with high expectations for their cultural experiences tend to struggle more with culture shock. Those who travel with an open mind and heart, who take the experiences as they come in a more spontaneous way tend to adapt better. Needless to say, the former roommate did not find his ideal partner and returned home sharing more stories of frustrating experiences rather than enriching ones.

When we travel to a new culture, the cultural distance between our home culture and host culture impacts our level of culture shock. This distance can be physical, but more importantly, cultural distance refers to the degree of difference in culture between the known, home environment and the new one. When we travel to destinations where people speak a different language, have different racial features, practice a different religion and have significantly different customs and traditions, we typically feel a greater degree of culture shock. As someone born and raised in Northern California, this author experienced much more culture shock when traveling to India than when visiting Vancouver, Canada.

Another factor that influences the degree of culture shock is sociocultural adjustment, which refers to the ability of the traveler to fit in and interact with members of the host culture. The level of sociocultural adjustment largely rests on the host's attitudes toward visitors to their culture. One attitude of hosts towards tourists is retreatism. Retreatism basically means that hosts actively avoid contact with tourists by looking for ways to hide their everyday lives. Tourists may not be aware of this attitude because the host economy may be dependent upon tourism. Such dependence could possibly force the host community to accommodate tourists with tolerance. Hawaii is a place that depends heavily on tourism and often uses various forms of retreatism to cope with the tourist invasion. Several students have mentioned that other than people who worked at restaurants or on tourist excursions, they didn’t see many locals when vacationing in Hawaii. Another attitude of hosts towards tourists is resistance. This attitude can be passive or aggressive. Passive resistance may include grumbling, gossiping about, or making fun of tourists behind their backs. Aggressive resistance often takes more active forms, such as pretending not to speak a language or giving incorrect information or directions. In the summer of 2019, Barcelona Mayor Ada Colau pledged to reduce the number of tourists, cutting cruise ships and limiting expansion of its airport. These actions came in response to an incredible surge of tourism. As The Guardian reported in 2016, the number of visitors making overnight stays in the city increased from 1.7 million in 1990 to more than 8 million in 16 years. That’s an astonishing increase for a city that is not as big as other European equivalents, such as Paris or London, and where many of the major tourist sites such as Sagrada Familia and Parc Güell are in residential areas where space to expand simply doesn’t exist. Further, traveling can be expensive, and travelers are often—but not always–more economically and socially privileged than their hosts. This dynamic can lead to power imbalances between hosts and tourists. Not all host attitudes are protective or negative. Some communities may capitalize on tourism and accept it as the social fabric of their community. Other communities actively invest money to draw tourists as a way to create economic well-being. This attitude is called revitalization. Residents do not always share equally in the revitalization, but sometimes it does lead to pride in the re-discovery of community history and traditions. Dolly Parton’s “Dollywood” located in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee was created as a way to revitalize a community that she loved much as eco-tourism is a revitalizing force in Costa Rica.

Of course, individual personality attributes play a factor in how well one copes with culture shock. Generally speaking, people with greater tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity respond better to unknown and unanticipated experiences that occur when encountering other cultures. Those who are inflexible or set in their ways tend to struggle more with culture shock. Experience matters here. First-time travelers are likely to experience more culture shock simply because of the novelty of the situation. Experienced travelers have experienced culture shock in the past and have developed coping mechanisms when they find themselves in that situation again. In 2017, the author of this chapter found himself hopelessly lost walking inside the Medina in Fez, Morocco. The Medina is a walled city formed in the 9th century. It is home to the oldest University in the world. The Medina consists of over 9,000 unmarked narrow alleyways. He had been walking for nearly 2 hours trying to get back to the guest house. He asked dozens of people for help, but due to language and cultural barriers, was having no luck. He had been warned that tourists shouldn't walk through the Medina alone at night, and as night began to fall, I started to wonder if I would ever find my way out of that incredibly complex labyrinth. Fortunately, this wasn't my first rodeo, as the saying goes. I had previously traveled to 47 different countries on 5 continents. He hiked a volcano alone in the middle of the night in Panama, trekked to the glacial source of the Ganges River in India, sat beside burning human bodies at cremation ceremonies in Nepal, and endured harrowing bus rides on roads cut from cliffs in the Andes of Bolivia. Drawing on those past experiences he didn't let culture shock get the best of me and eventually found his way back home.

Stages of Cultural Shock

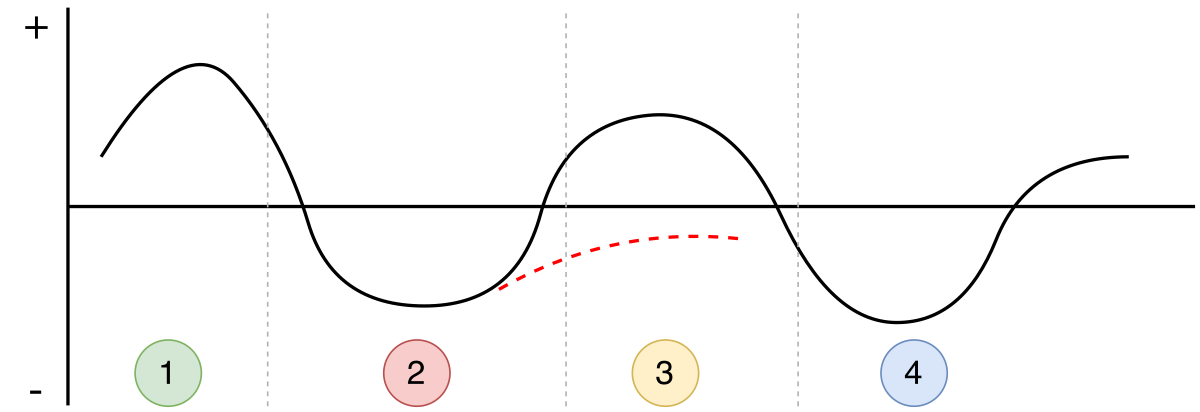

The experience of culture shock can range from mildly annoying to profoundly disturbing. Fortunately, many studies have been conducted and a few models have emerged that help explain the stages of culture shock. When we have a better understanding of this phenomenon, we are better suited to manage it. One of the best-known models is The W-curve model, proposed by Gullahorn and Gullahorn (1963). The W shape represents the fluctuation of travelers' emotions when adapting to a new culture, and then when re-adapting to their home culture.

To understand this model, the vertical axis represents satisfaction or happiness, and the horizontal axis represents time. The first stage, often called the honeymoon stage, happens right at the beginning of the journey. It represents the hope and excitement in anticipation of new experiences. For students who study abroad, the honeymoon stage signifies the start of the adventure. The long-awaited day has finally come! In this stage, the traveler may become infatuated with the language, food, people, and overall environment of the host culture. Stage two, the culture shock stage, is characterized by frustration and fatigue of not understanding the norms of the new culture. Common symptoms of the culture shock stage include homesickness, feelings of helplessness, disorientation, isolation, depression, irritability, sleeping and eating disturbances, loss of focus, and more. As time progresses, the traveler begins to become more comfortable with the new environment. Navigating the new culture becomes easier, friendships and communities of support are established, and the language and customs become more familiar. This adaptation to the new culture is the third stage, called the adjustment stage. The longer one stays in a new culture, the more one acclimatizes to it. These first three stages represent time spent in the new culture. This U-shape describes many of the early models of culture shock. The W-curve model expands on earlier models and recognizes that the return home can be marked by feeling let down and mental isolation. This fourth stage is referred to as reverse culture shock or re-entry shock. Traveling can be profoundly enriching, even life-changing. Many students who have studied abroad claim it was the most significant thing they had done in their lives. When they first arrive home, they are eager to share their experiences with family and friends. This initial eagerness quickly fades as they have trouble relating the profound experience to those who stayed home. Further, they realize that nothing at home has changed and people grow tired of their stories and just want the traveler to return to "normal," meaning the way they were before the journey. The traveler has a new sense of identity that is not validated by their loved ones. Fortunately, through time, the traveler accepts their home culture and integrates their experiences into a new sense of self.

Some scholars have suggested other models for describing the process. Young Yun Kim (2005) sees adjustments happening in a cyclical pattern of stress – adaptation – growth. She sees stress as useful for an individual's growth and prefers "cultural adjustment" over "culture shock". It's also the case that acculturation is not just within the power of the individual. It also depends on the willingness of the host culture to accept (or not) the individual. A physician or engineer from abroad coming into a new country will likely be given a much better reception than poor immigrants; this can have a significant impact on the adjustment process. It can be the case as well that the co-cultures in the new country may be welcoming to the new arrival, if there are similarities which make acculturation smoother, such as national origin, sexual orientation, or professional affiliations. Adjusting to a new culture is facilitated by the presence of linguistic or cultural resources linked to the home culture, such as food markets, schools, and clubs.

As with all explanatory models, it is important to remember that there is no one-size-fits-all model. Some people skip certain stages, experience them in a different order, or have a longer or shorter adjustment period than others. What researchers do agree upon is that it is natural to feel some degree of culture shock. Although most people recover from culture shock fairly quickly, a few find it to be profoundly disorienting, and take much longer to recover, particularly if they are unaware of the sources of the problem, and have no idea of how to counteract it. The following tips can help travelers manage the emotional roller coaster of culture shock.

Tips for Managing Culture Shock

One of the best remedies for managing culture shock starts with simply understand that culture shock exists. Culture shock can catch us by surprise. We feel emotions that we don't expect or are novel to us. A traveler once told me, "I don't know what's happening. I've always been really easy going, but lately I feel irritable all the time, even aggressive. This is not me." When we realize that culture shock exists, we have an explanation for the emotional turmoil caused by culture shock. If we don't know about culture shock, we are left wondering, "what's happening to me"," which can be profoundly unsettling. Many years ago, I was traveling through Honduras with a few other sojourners I met along the way. One afternoon, a young woman in our cohort just started crying. We asked her what happened and why she was crying. She just shook her head, and through her tears she said "Nothing happened, I don't know why I am crying!" In hindsight, it was clearly an effect of culture shock.

Culture shock by definition is the stress and anxiety we experience when we are in unfamiliar territory. Therefore, if we learn more about the host country, we may begin to have an understanding of the different norms and customs in our new environment. If we know we will be traveling, we should do our homework. There are countless guidebooks and websites that discuss different cultural tendencies exhibited by people of different nations. For example, cultureready.org has country specific information on greetings, communication style, gender issues, law and order, dress, socializing, business basics, and gift giving, to name just a few.

In the summer of 2005, the author of this chapter accepted a visiting professor position in Chengdu, China. Chengdu is a large city in western China. Very few locals spoke English, and the language difference between Mandarin and English is significant, making communication nearly impossible. Knowing that trying to bridge this language barrier is daunting, the resident director had students break into small groups and go to different sites within the city on the public busses on the first day. Once students arrived at their respective sites, they had some time to look around and then take a taxi to reconvene in the larger group for lunch. All students were given a small card with the name and address of the restaurant written in Chinese to hand to the taxi driver. This strategy was meant to give students an early opportunity to get out and experience the culture. In retrospect, this was an excellent strategy to help students manage culture shock. A common coping mechanism when confronting culture shock is to turn inward, and isolate oneself the host culture. Some people may choose to stay in their rooms all day instead of interacting with others. A better approach is to develop friendships or acquaintances with the locals. In Chengdu, there were certain locations called English corners, where people gathered to practice English. The American students who went to the English corners were surrounded by local Chinese people who invited them to their homes, took them out for meals, and showed them the hidden jewels of the city that they otherwise never would have encountered. To help meet locals, students who study abroad are encouraged to join campus clubs or community organizations that match their interests. When the author of this chapter taught in Spain for a semester, the study abroad organization set up intercambios between American study abroad students and local Spanish students. The stated purpose of these intercambios were for each party to practice the others' language, but they also served as a way for American students to meet locals and integrate into the local culture. The author had a hard time meeting locals when he spent a week in Jamaica. He didn't like being perceived as just another white tourist, staying in the boundaries of an all-inclusive hotel. As a life-long soccer player, he started joining the local pick-up soccer games in the evenings. This was a perfect way to get to know local people outside of the oppressive relationship of the servers and the served.

When we enter an unfamiliar culture, we confront situations that we just don't understand. We may not understand the language people use when speaking to us. We might not understand the behavior of the locals, the significance of ceremonies, etc. To better manage culture shock, we need to learn to tolerate ambiguity. You can frustrate yourself to no end if you need to have explanations for everything happening all around you, all the time. By tolerating ambiguity, we become more comfortable with knowing that there is so much happening that we just don't understand, and that's okay. One of my favorite examples comes from traveling in rural Tibet. It was common for children to approach me and stick out their tongues at first greeting. I had no idea why this kept happening to me. Later I learned that this was a common greeting. According to Tibetan folklore, a cruel ninth-century Tibetan king had a black tongue, so people stick out their tongues to show that they are not like him (and aren't his reincarnation).

Humans have a natural desire to reduce uncertainty in any given situation. When traveling through unfamiliar cultures, the increased levels of uncertainty can leave people feeling insecure. This insecurity is often projected outward and can manifest in disparaging the norms of the host culture. It is easy to compare our home culture with the unknown, and this can lead to ethnocentric thinking. Ethnocentrism is the tendency to evaluate other groups according to the values and standards of one's own ethnic group, especially with the conviction that one's own ethnic group is superior to the other groups (dictionary.com). The best advice for managing culture shock is be mindful of ethnocentrism and suspend ethnocentric evaluations.

Culture shock is stressful. Our attitude can profoundly influence our experience. To manage that stress, we need to cultivate a positive attitude. We can't always change our environment, but we can change how we react to it. It's important to have faith in yourself, in the essential goodwill of your hosts, and the positive outcome of the experience. Not everybody is out to get you. If someone laughs, it doesn't mean they are laughing at you. Of course, we need to be careful when traveling abroad, but we don't need to be afraid. The most enriching experiences don't come from visiting historical landmarks, they come from deep, authentic connections we make with people along the way. The author shares that he can always remember visiting the Taj Mahal in India. But what warms his heart is sharing the long train journey with an Indian family, sharing food, and singing songs along the way.

- Be flexible and try new things.

- Get involved in the things that you already like.

- Do not expect to adjust overnight.

- Process your thoughts and feelings.

- Use the resources available to help you handle the stress.

Attributions

Adapted from:

Exploring Intercultural Communication by Tom Grothe. Provided by LibreTexts. License: CC-BY-NC-SA

Image Attributions

Outdoor market in Chengdu, China by Tom Grothe is used under CC-BY license.

Backpacking in a Busy City by Stephen Lewis.

References

Cohen, E. (1972). Toward a sociology of international tourism

Godwin-Jones, R. (2016). Emerging Technologies Integrating Technology into Study Abroad. Language Learning & Technology

Groethe, T. (2022). Exploring Intercultural Communication. Provided by LibreTexts. License: CC-BY-NC-SA

Krumrey-Fulks, K. (2021). Intercultural Communication for the Community College. Provided by LibreTexts. License: CC-BY-NC-SA

Kinginger, C. (2008) Language Learning in Study Abroad: Case Studies of Americans in France. The Modern Language Journal.

Oberg, K. (1960) Cultural Shock: Adjustment to New Cultural Environments. Practical Anthropology.

Salisbury, M. H., An, B. P., & Pascarella, E. T. (2013). The Effect of Study Abroad on Intercultural Competence Among Undergraduate College Students. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice