2.6: Describing vowels

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 199877

- Catherine Anderson, Bronwyn Bjorkman, Derek Denis, Julianne Doner, Margaret Grant, Nathan Sanders, and Ai Taniguchi

- eCampusOntario

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Vowel quality

Vowel phones can be categorized by the configuration of the tongue and lips during their articulation, which determines the vowel’s overall vowel quality. Vowel quality is often much more of a continuum than consonant categories like place and manner. A slight change in articulation makes little difference in what a vowel sounds like, but it can have a drastic effect on a consonant. For example, moving an active articulator away from a passive articulator by just a tiny bit, less than 1 mm, is enough to turn a stop into a fricative, but that same distance for a vowel will have no noticeable effect. However, we can still identify several broad categories of vowel qualities based on dividing up this continuum into a few major regions.

Height

Vowels are articulated with a larger opening in the oral cavity than consonants are, requiring the tongue to move farther down than for approximants. This is typically facilitated by also moving the jaw down to allow the tongue to move even lower. The height of the tongue during the articulation of a vowel is called vowel height, or simply height for short.

A vowel with a very high tongue position, as in the English word beat, is called a high vowel. Some linguists instead call this a close vowel, but we will not use that terminology here. High vowels have an opening just slightly larger than for approximants. Indeed, high vowels and approximants are often related in many languages, with one turning into the other in certain positions. Compare the different pronunciations of the phone represented by the letter i in the middle of the English words unique (with a high vowel) and union (with an approximant).

A vowel with a very low tongue position, as in the English word bat, is called a low vowel. Again, some linguists have a different term that we will not use, calling these vowels open instead. Low vowels have the largest opening of any phone, whether vowel or consonant.

A vowel with an intermediate tongue position between high and low, as in the English word bet, is called a mid vowel. The differences in vertical tongue position for these three categories of vowel height are shown in Figure 3.\(\PageIndex{1}\), from highest on the left (as in beat) to lowest on the right (as in bat). Note how the jaw also lowers along with the tongue in these diagrams.

The horizontal position of the tongue, known as its backness, also affects vowel quality. Backness could equally be called frontness, and sometimes this term is used, but backness is more standard and preferred. If the tongue is positioned in the front of the oral cavity, so that the highest point of the tongue is under the front of the hard palate, as for the vowel in the English word beat, the vowel is called a front vowel.If the tongue is positioned farther back in the oral cavity, so that the highest point of the tongue is under the back part of the hard palate or under the velum, as in the English word boot, the vowel is called a back vowel.

If the tongue is positioned in the centre of the oral cavity, so that the highest point of the tongue is roughly under the centre of the hard palate, in between the positions for front and back vowels, as for the English word but, the vowel is called a central vowel. Be careful not to confuse the technical terms central and mid. Central refers to an intermediate position in backness, while mid refers to an intermediate position in height. These two terms are not interchangeable! The differences in horizontal tongue position for these three categories of vowel backness are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\). from frontest on the left (as in beat) to backest on the right (as in boot).

Note that what counts as front for a vowel depends on its vowel height, because of how the jaw moves. Humans have a hinged jaw, which means that as the jaw moves down to allow for a lower tongue position, the jaw also swings backward, carrying the tongue along with it. As the tongue moves backward due to this hinged movement, its centre position also moves backward, and it becomes more difficult for this lowered tongue to move as far forward as for a higher vowel.

In fact, the frontest position for a low vowel (as in the English word bat) typically has an actual overall backness a bit farther back than for a front high vowel (as in the English word beat). Thus, backness must be defined relative to the possible range of horizontal positions at a given height, rather than being defined in absolute terms with respect to the roof of the mouth. This results in a skewed shape of the possible combinations of vowel height and backness, with more distance between front and back positions for high vowels than for low vowels.

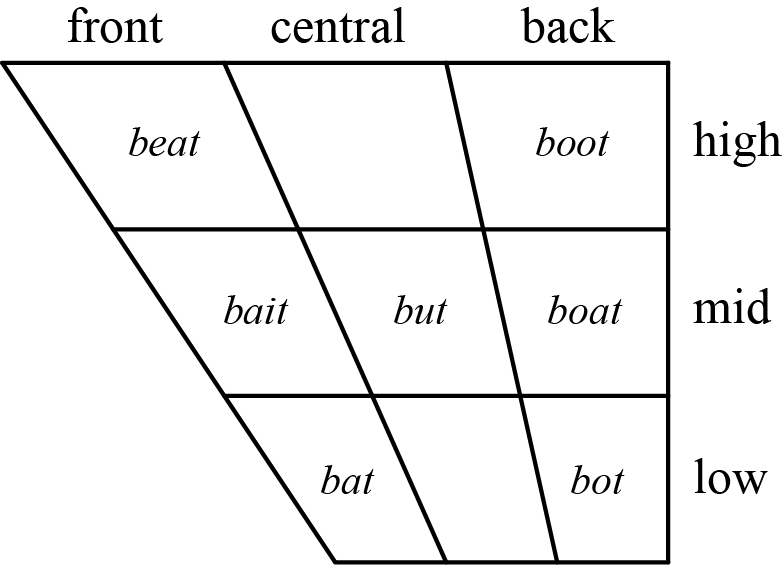

This is often graphically represented as in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), with the total vowel space drawn as an asymmetric quadrangle, like a rectangle with the bottom left corner cut off. This missing corner represents the space where humans cannot produce a vowel because of the how the tongue moves backward as the jaw lowers. A few example words of English are listed in Figure 3.15 as rough indications for what tongue position many speakers use for the vowels in these words.

The cells in this quadrangle represent possible positions of the tongue within the oral cavity. For example, beat is shown in the high front cell, which indicates that it is pronounced with a high front tongue position. Note that there is much variation in English vowels across speakers, so the positions in Figure 3.15 are only meant to be suggestive of broad patterns across a range of dialects. The positions of the tongue for the vowels in these words may be somewhat different for you or for other speakers. For example, some speakers may have a low or back vowel for but, and some may have a more central vowel for bot or boat.

Rounding

Vowel quality also depends on the shape of the lips, generally referred to as the vowel’s rounding. If the corners of the mouth are pulled together so that the lips are compressed and protruded to form a circular shape, as for the vowel in the English word boot in many dialects, the lips are said to be rounded and the corresponding vowel is called a round or rounded vowel.

If the corners of the mouth are pulled apart and upward so that the lips are thinly stretched into a shape like a smile, as for the vowel in the English word beat, the lips are said to be spread.

The lips may also be in an intermediate configuration, neither rounded nor spread, as for the vowel in the English word but, in which case, the lips are said to be neutral. Spread and neutral vowels are collectively referred to as unrounded or non-rounded vowels, because the distinction between spread and neutral lips seems almost never to be needed in any spoken language, whereas the distinction between rounded and unrounded frequently is needed. The differences in lip shape for these three categories of vowel rounding are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\).

Tenseness

The position of the tongue root may also play a role in vowel quality. If the tongue root is advanced forward away from the pharyngeal wall, as for the vowel in the English word beat, the tongue root pushes into the rest of the tongue. This causes the tongue to be somewhat denser and firmer overall, so a vowel with an advanced tongue root is sometimes called a tense vowel. If the tongue root is instead in a more retracted position closer to the pharyngeal wall, as for the vowel in the English word bit, it keeps the tongue somewhat more relaxed, so a vowel with a retracted tongue root is sometimes called a lax vowel. The property of whether a vowel is tense or lax is called tenseness. The different positions of the tongue root for tense and lax vowels are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\).

For many spoken languages, vowel tenseness is not a relevant property. Languages like Taba (a.k.a. East Makian, a Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian language of the Austronesian family, spoken in Indonesia) have only five vowels that are spread quite far apart. There is only one high front vowel, one mid front vowel, etc. These vowels can vary in how tense or lax they might be from one pronunciation to the next, so there is no need to use the terminology tense and lax to describe them.owever, other spoken languages have more complex vowel systems, with vowel pairs articulated in roughly the same way, except for tenseness. For example, most dialects of English have multiple pairs of vowels that are distinguished primarily by tenseness, such as the vowels in beat and bit. Both of them have a high front tongue position and are unrounded, but the beat vowel is tense, while the bit vowel is lax. Similarly, the vowels of the English words bait and bet are both front, mid, and unrounded, but the bait vowel is tense, while the bet vowel is lax. Thus, for languages like English, the tense/lax terminology is often necessary to fully describe the vowel system.

That said, low vowels are very rarely tense in any language, because lowering the tongue and advancing the tongue root are making almost contradictory demands on the tongue, pushing the bulk of tongue in two different directions. However, the tongue is quite flexible and can physically be both lowered and tensed, so tense low vowels are not impossible, and there are some languages that have them, such as Akan (a Kwa language of the Niger-Congo family, spoken in Ghana), which has both a tense and a lax low vowel.

Nasality

In Section 3.4, we talked about how the velum can move to make a distinction between oral and nasal stops based on whether or not air can flow into the nasal cavity. The same distinction can be for vowels. If a vowel is articulated with a raised velum to block airflow into the nasal cavity, the vowel is called oral. If instead the velum is lowered, allowing airflow into the nasal cavity, the vowel is called nasal or nasalized. The property of whether a vowel is oral or nasal is called its nasality. Vowels in most dialects of English are often nasal when they are immediately before a nasal stop, as in the English word bent. The different positions of the velum for oral and nasal vowels are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\), with arrows indicated direction of airflow.

Length

In addition to differences in vowel quality and nasality, vowels may also differ from each other in length, which is a way of categorizing them based on their duration. In most spoken languages where vowel length matters, there is just a two-way distinction between long vowels and short vowels, with long vowels having a longer duration than their short counterparts. For example, in Japanese (a Japonic language spoken in Japan), the word いい ii ‘good’ has a long vowel, while the word 胃 i ‘stomach’ has a short vowel, although they both have the same vowel quality: they are both high front unrounded vowels. The pronunciation of these two Japanese words can be heard in the following sound file, first いい ii with a long vowel, then 胃 i with a short vowel.

lowers to a mid position, and then finally ends in a high back position with rounding. The pronunciation of this Vietnamese word can be heard in the following sound file.

In most dialects of English, vowel length is not used to distinguish words with completely different meanings like it is in Japanese. However, English vowels can still differ in vowel length in some circumstances. For example, English vowels are often pronounced a bit longer before voiced consonants than before voiceless consonants. Thus, the vowel in the English word bead is usually pronounced longer than the vowel in the word beat, even they both have the same vowel quality: high front unrounded. The tense vowels of English also tend to inherently be a bit longer than their lax counterparts. For example, the tense vowel in the English word beat is longer than the lax vowel in bit.

Consonants may also differ from each other in length. Long consonants are often called geminates, while short consonants are called singletons. English does not really make regular use of consonant length, though there are some marginal examples for some speakers, such as unnamed (with a geminate alveolar nasal stop) versus unaimed (with a singleton alveolar nasal stop). However, many other languages have widespread distinctions based on consonant length.

For example, geminates and singletons are contrasted in Hindi (a Central Indo-Aryan language of the Indo-European family, spoken in India). Hindi has word pairs like सम्मान sammān ‘honour’ (with a geminate bilabial nasal stop in the middle of the word) versus समान samān ‘equal’ (with a singleton bilabial nasal stop in the middle of the word). The pronunciation of these two Hindi words can be heard in the following sound file, first सम्मान sammān with a geminate consonant, then समान samān with a singleton consonant.

lowers to a mid position, and then finally ends in a high back position with rounding. The pronunciation of this Vietnamese word can be heard in the following sound file.

Multiple vowel qualities in sequence

Many vowels of the world’s spoken languages have a relatively stable pronunciation from beginning to end. These kinds of stable vowel phones are called monophthongs. However, just as there are dynamic consonant phones (affricates), vowel phones may also change their articulation from beginning to end. Most of these are diphthongs, which begin with one specific articulation and shift quickly into another, as with the vowel in the English word toy, which begins with a mid back round quality but ends high, front, and unrounded. As with affricates, it can be difficult to determine whether a given change in vowel quality is best treated as a true diphthong or instead as a sequence of two separate monophthongs.

Some languages can even have triphthongs, which are vowel phones that change from one vowel quality to another and then to a third, as in rượu ‘alcohol’ in Vietnamese (a Viet-Muong language of the Austronesian family, spoken in Vietnam and China). The word rượu has a vowel phone that begins with a high central unrounded quality, then lowers to a mid position, and then finally ends in a high back position with rounding. The pronunciation of this Vietnamese word can be heard in the following sound file.

Putting it all together!

There is not as much consistency in the order of descriptions for vowels as for consonants. Perhaps the most common order is height – backness – rounding, but rounding is sometimes given first instead, and though height is usually given immediately before backness, these can also be switched. Thus, the vowel in the English word bet might be described as a mid front unrounded vowel, or as an unrounded mid front vowel, or as a front mid unrounded vowel, or as an unrounded front mid vowel. All of these would be considered correct, and other combinations may be used.

When descriptions of nasality are needed, they are almost always placed after the description of vowel quality. Thus, the vowel in the English word bent might be described as a mid front unrounded nasal vowel, or as an unrounded mid front nasal vowel, but rarely as a nasal mid front unrounded vowel.

If descriptions of tenseness or length are also needed, these are often placed before the other descriptions, but sometimes either or both may be placed after vowel quality, but usually still before the position for the description for nasality. Thus, the vowel in the English word bend could be described as a long lax mid front unrounded nasal vowel, or as a lax mid front unrounded long nasal vowel, or as an unrounded mid front long lax nasal vowel, or many other combinations!