9.6: Adults are not children

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 200005

- Catherine Anderson, Bronwyn Bjorkman, Derek Denis, Julianne Doner, Margaret Grant, Nathan Sanders, and Ai Taniguchi

- eCampusOntario

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/essentialsoflinguistics2/?p=2630#oembed-1

In many Intro Linguistics textbooks, this chapter would be titled Second Language Acquisition (SLA), which is also the common name for the subfield of linguistics that studies adult language learning. The label SLA encodes an assumption that the typical learner is proficient in exactly one language — the first language, which was acquired “natively” — and that the subsequent language is therefore the second one. That assumption is quite narrow, given that about one-third of people in the world use two different languages regularly, and many of those people use three or more languages (Wei, 2007). A similar assumption is embedded in academic programs that require credit in a “foreign” language: foreign to whom? These terms reveal the Anglocentrism of the field by implicitly assuming that a typical learner speaks English as their first language and learns something other than English, that is, something foreign, as their second language.

The same assumption is contained within in the label English as a Second Language (ESL), which highlights the otherness of those who learn English in adulthood. Some teachers of English to adults use terms like additional language or other language, which don’t encode quite the same assumptions. And so-called foreign languages are now sometimes referred to as world languages. As we learned in Chapter 2, there are few, if any, truly neutral terms for discussing human differences. In this chapter we’ll use the terms L1 or first language for any language learned from early childhood, even if the learner acquires more than one at once, and later language for any language learned after the first one(s).

In fact, that’s one key difference between learning a first language and learning a later one: you already have one mental grammar when you start acquiring another one. In a later unit we’ll consider how the grammar of your L1 influences the grammars of your later languages. The other key difference is that adults are different from children.

Cognitive and Linguistic Differences

As the previous chapter showed, language learning is not usually difficult or effortful for young children. As long as they’re in an environment where they have access to language used by adults, they’ll learn it pretty quickly. One reason it’s so easy for little ones is because of their neural plasticity: their brains are super-keen to make new connections in response to their experiences. The older you get, the harder it is for your brain to grow new neural pathways, so the harder it is to learn new things. It’s not impossible by any means, it just takes more effort!

On the other hand, adults have some advantages over children. We have metacognitive skills we can apply consciously to language learning, such as memorizing new vocabulary and morphology, choosing to study a little bit each day, or seeking out books, movies, podcasts or other media in our new language. We also have metalinguistic awareness that we can employ. For example, we can consciously practice placing our articulators in new positions, or we can compare and contrast the syntactic structures in our new language with those from our L1.

Socioemotional Differences

Another factor that can make language learning harder for adults than for children is our self-consciousness. Learning a new language usually involves interacting with other people, including other people who are more proficient than us. If you’re adult who’s used to being seen as competent, it can be embarrassing to feel like a beginner and to make mistakes.

Like the field of Linguistics as a whole, the subfield of Second Language Acquisition is often narrowly focused on grammar, especially on acquiring phonetics, morphology and syntax. This approach to teaching and learning is related to colonial ways of thinking that treat language as an object or asset that can be acquired in isolation from people, communities, and relationships (Czaykowska-Higgins et al., 2017; Lukaniec & Palakurthy, 2022; MacKenzie et al., 2022).

But as we’ve been learning throughout this book, language is not just a collection of structural properties! Chapter 2 showed that our language use is interwoven with our emotions and identities. And unlike babies developing an L1, adult language learners bring all kinds of cultural knowledge, traditions, expectations and, yes, emotions to our language learning, which we may or may not be consciously aware of. The next unit will look at these socioemotional factors in more detail .

Check your understanding

Query \(\PageIndex{1}\)

References

Czaykowska-Higgins, E., Burton, S., McIvor, O., & Marinakis, A. (2017). Supporting Indigenous language revitalisation through collaborative post-secondary proficiency-building curriculum. In W. Y. Leonard & H. De Korne (Eds.), Language Documentation and Description (Vol. 14, pp. 136–159). EL Publishing.

Lukaniec, M., & Palakurthy, K. (2022). Additional Language Learning in the Context of Indigenous Language Reclamation. In K. Geeslin, The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition and Sociolinguistics (1st ed., pp. 341–355). Routledge.

MacKenzie, A., Engman, M., & McGurk, O. (2022). Overt and symbolic linguistic violence: Plantation ideology and language reclamation in Northern Ireland. Teaching in Higher Education, 1–12.

McIvor, O. (2020). Indigenous Language Revitalization and Applied Linguistics: Parallel Histories, Shared Futures? Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 40, 78–96.

Wei, L. (2007). Dimensions of Bilingualism. In L. Wei (Ed.), The bilingualism reader (2nd ed., pp. 3–22). Routledge.

12.2: Motivations for adult language learners

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/essentialsoflinguistics2/?p=2633#oembed-1

It wouldn’t make sense to think about the motivations of infant language learners: they can’t help learning whatever language they have access to. In contrast, adult language learners may have any number of different reasons to learn a language, and their motivations affect the ways they learn.

Migration, Employment, and Education

As we saw in Chapter 2, many employers in Canada expect their employees to be proficient in English. If you immigrate to Canada for work or for school, you have a pretty clear economic motivation to learn English. Unfortunately, the common approaches to teaching English to adult learners are often built on standard language ideologies with racist and colonialist assumptions. Such classes frame English as a fixed asset contained in textbooks. In their analysis of ESL classes, Swift argues, “the language that students saw and heard seemed to be designed to represent prescriptive norms (sometimes to the point of hyper-formality/correction) rather than believable examples of real-life practice.” (2022, p. 317). In these contexts, the teacher is the ultimate arbiter of correctness, and as Ramjattan (2019b) shows, white people are perceived as better teachers than people of colour.

Rosa & Flores (2021) point out that a prescriptivist approach to teaching ESL is usually intended benevolently. The underlying reasoning is that adult learners, often people of colour who have immigrated, need to learn standardized forms of English so they can have workplace success and be included in mainstream society. But this logic is flawed: we know from Chapter 2 that listeners’ perception of a “foreign” accent in English is influenced by the speaker’s appearance as much as by their speech (Babel & Russell, 2015) and Ramjattan (2019a) reminds us that employers disguise their racial discrimination by cloaking it in terms of accent. Rosa & Flores sum it up this way:

“even when marginalized people within these contexts engaged in linguistic practices that seemed to correspond to mainstream standards, they continued to be perceived as deficient and in need of remediation.” (Rosa & Flores, 2021, p. 1164)

In other words, even so-called “perfect” English – that is, English that matches the prestige standard – is often not enough to escape raciolinguistic stigma. A growing body of literature considers how ESL teachers might embrace variation in English and resist stigmatizing their students’ language practices. If you’re interested in language teaching, maybe you’ll be interested in working towards social justice in an ESL class!

Cultural Enrichment

Rather than employment, your primary motivation for learning a later language might be for intellectual or cultural enrichment. The idea is that your worldview can be expanded by learning about a culture other than your own. There might be the incentive of international travel, an exchange or a semester abroad. The languages taught and learned in this context used to be labelled as foreign languages, with the unspoken implication that anything not English is foreign. These days you more often see the terms international languages or world languages to refer to languages other than English.

Regardless of the label, curriculum and teaching materials for this kind of later language learning tend to assume that the learner is a white speaker of English. Anya (2021) showed that the curriculum for college Spanish in the USA systematically excluded Black learners in several ways: not only were African-American cultural occasions and news stories disregarded, but even the Spanish vocabulary for describing people’s appearance did not include appropriate terms for African descendants. Black students in these classes felt that learning Spanish was irrelevant to them.

You can see from the dates of the research I’ve mentioned here that the field of adult language learning is only recently beginning to grapple with the racist assumptions embedded in its practices. If you’re learning a later language, maybe you can challenge some of those assumptions in your own class. Or if you go on from studying linguistics to become a language teacher, maybe you can work to incorporate racial and social justice into world language learning!

Community Connection

The languages spoken by Indigenous peoples in North America don’t usually fall into the category of “world languages” because of their particular status. As we saw in Chapters 1 and 9, the colonial Canadian government engaged in systematic and often violent efforts to eradicate these languages and assimilate their speakers into the colonizers’ white English-speaking society. This is why learning the languages of their Nations is vitally important for many Indigenous adults who did not have the opportunity to learn their language as children. Learning it as an adult allows them a connection with their Elders’ stories and teachings. Many strive to gain enough proficiency so that their children can learn their language at home, in childhood: this is one of the best means of ensuring that the language continues to be used.

Ferguson and Weaselboy (2020) explain eloquently how many Nations’ traditional teachings about culture and about the Land are thoroughly embedded within each Nation’s language. They argue, “Land must be experienced through Indigenous language in order to fully appreciate those layers of meaning and appreciate the nuances of what sustainable relations are within that Indigenous culture.” (2020, p. 3) Jenny Davis discusses the ways that people working to reclaim Indigenous languages embed their work in “the robust geographic, linguistic, spiritual, and social dynamics of languages” (Davis, 2017, p. 49); she describes these strategies as a means of survivance, blending survival of the language with resistance to colonial oppression.

One of Wesley Leonard’s language reclamation activists expressed this idea of the rich connections between language and community by taking about morphology. In the myaamia language, the verb that means “to speak a language” is a bound morpheme. One myaamia speaker pointed out that the verb –aatawee– “can’t stand alone; we have to attach it to the people” (Leonard, 2017, p. 30)

Because Canadian universities are by and large founded on Euro-Western colonial ideals, a typical university course is not necessarily the most effective or appropriate venue for adult learners of Indigenous languages. Czaykowska-Higgins and her colleagues (2017) describe how the language programme at the University of Victoria strives to be “responsive to the needs and directions expressed by First Nations community partners, and by doing so, to support the empowerment and self-determination of those communities.” (2017, p. 142)

One way that adult learning of Indigenous languages might differ from other later language learning is the specific barriers that Indigenous learners may encounter. In Chapter 9, Mary Ann Corbiere and David Kanatawakhon Maracle both talk about the fact that there simply aren’t many opportunities for learners to practice their languages, because there are few speakers and few materials like books, reference grammars, and curriculum resources. And McIvor (2020) points out that Indigenous learners often carry multi-generational trauma specifically about their languages, because of their or their relatives’ experiences of violence in colonial schools.

On the other hand, some Indigenous language learners also report substantial benefits to their mental and physical health as they gain proficiency in their language. For example, Oster et al. (2014)’s quantitative analysis of 31 First Nations in Alberta showed that the Nations with higher language proficiency had lower rates of diabetes. Similarly, in an analysis of First Nations in British Columbia, Hallett et al. (2007) found that the communities with the highest numbers of speakers of the language had the lowest suicide rates among youth.

Of course, it would be too simple to interpret these results to mean that grammar leads to good health. Instead, these quantitative measurements align with what Indigenous Elders and experts say about the deep connections between their languages and the traditional cultures of their communities. One of the participants in Oster et al.’s interviews of members of the Piikani Blackfoot Nation and Ermineskin Cree Nation explains it this way:

“Elders always speak of the importance of our language. Who we are is determined through our language. We speak our language and that determines where you come from, what your culture is, and even how we used to go with the different seasons in terms of following those traditional paths. Regardless of where you go, if you have that language our culture is in there… So once you lose that, what do you have left? Because our beliefs come from that in terms of how we govern ourselves. It comes in terms of how we eat, and in terms of how we educate ourselves and conduct ourselves in that full circle.”

(quoted in Oster et al., 2014, pp. 3-4)

And Gisele Maria Martin, a Nuu-chah-nulth learner quoted by McIvor (2020), says it even more simply and eloquently. She says:

“I have found a part of my soul that was missing. I just feel so grateful. I feel like it’s one of the biggest, most meaningful things I’ve ever done in my life.” (quoted in McIvor, 2020, p. 89)

How’s that for motivation? Reclaiming your language might mean finding part of your soul.

Check your understanding

Query \(\PageIndex{1}\)

References

Anya, U. (2021). Critical Race Pedagogy for More Effective and Inclusive World Language Teaching. Applied Linguistics, 42(6), 1055–1069.

Babel, M., & Russell, J. (2015). Expectations and speech intelligibility. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 137(April), 2823–2833.

Czaykowska-Higgins, E., Burton, S., McIvor, O., & Marinakis, A. (2017). Supporting Indigenous language revitalisation through collaborative post-secondary proficiency-building curriculum. In W. Y. Leonard & H. De Korne (Eds.), Language Documentation and Description (Vol. 14, pp. 136–159). EL Publishing.

Davis, J. L. (2017). Resisting rhetorics of language endangerment: Reclamation through Indigenous language survivance. In W. Y. Leonard & H. De Korne (Eds.), Language Documentation and Description (Vol. 14, pp. 37–58). EL Publishing.

Ferguson, J., & Weaselboy, M. (2020). Indigenous sustainable relations: Considering land in language and language in land. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 43, 1–7.

Hallett, D., Chandler, M. J., & Lalonde, C. E. (2007). Aboriginal language knowledge and youth suicide. Cognitive Development, 22(3), 392–399.

Leonard, W. Y. (2017). Producing language reclamation by decolonising ‘language.’ In W. Y. Leonard & H. De Korne (Eds.), Language Documentation and Description (Vol. 14, pp. 15–36). EL Publishing.

Lukaniec, M., & Palakurthy, K. (2022). Additional Language Learning in the Context of Indigenous Language Reclamation. In K. Geeslin, The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition and Sociolinguistics (1st ed., pp. 341–355). Routledge.

McIvor, O. (2020). Indigenous Language Revitalization and Applied Linguistics: Parallel Histories, Shared Futures? Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 40, 78–96.

Oster, R. T., Grier, A., Lightning, R., Mayan, M. J., & Toth, E. L. (2014). Cultural continuity, traditional Indigenous language, and diabetes in Alberta First Nations: A mixed methods study. International Journal for Equity in Health, 13(1), 92.

Ramjattan, V. A. (2019a). Racializing the problem of and solution to foreign accent in business. Applied Linguistics Review.

Ramjattan, V. A. (2019b). The white native speaker and inequality regimes in the private English language school. Intercultural Education, 30(2), 126–140.

Rosa, J., & Flores, N. (2021). Decolonization, Language, and Race in Applied Linguistics and Social Justice. Applied Linguistics, 42(6), 1162–1167.

Swift, K. (2022). ‘The good English’: The ideological construction of the target language in adult ESOL. Language in Society, 51(2), 309–331.

9.6: Second Language Acquisitions Theories and Components

Second Language Acquisition Theories and Components, from Sarah Harmon

Video Script

Every single one of you has attempted to learn a second language; in some cases, you may have been successful, while in other cases, not so much so. As we go through these next few sections about second language acquisition, keep in mind your own experiences. I'm sure some of them, if not all of them, will be reflected in what we talk about.

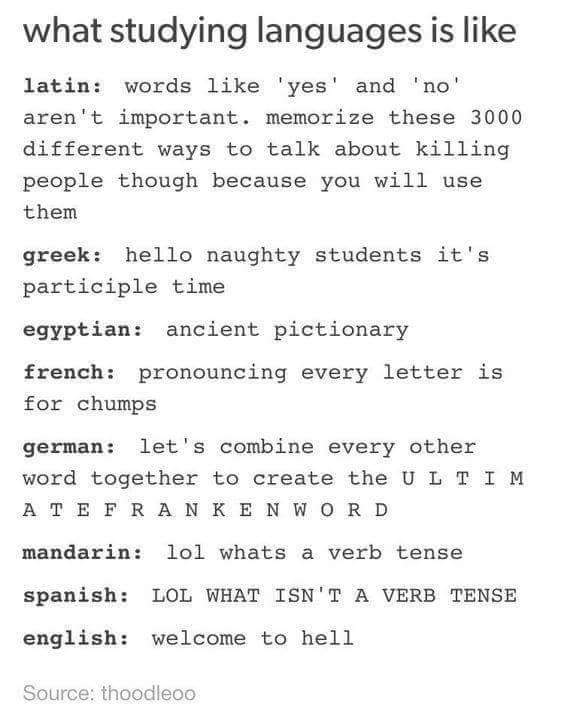

To start things off, this was a hilarious meme that came through Facebook years ago.

Having learned or attempted to learn a couple of these languages, I can relate. For a bit more context:

- Latin: The fact that Latin doesn’t have specific lexicon for ‘yes’ and ‘no’, but there seems to be 3,000 different ways to talk about killing people.

- Ancient Greek: There's so many different derivations of verbs that you never knew existed until you look at Ancient Greek.

- Ancient Egyptian: The hieroglyphs are the connection.

- French: Certainly, if you tried to learn or if you have learned French, it seems that half of what you see written doesn't get pronounced

- German: If you go back to morphology, we looked at German compounding; look up the word for ‘research’ in German, and that should tell you some things.

- Mandarin: Remember, it’s an isolating language.

- Spanish: Remember, it’s a fusional language and a synthetic language.

- English: Okay, maybe not maybe not hell, maybe not the easiest language to learn.

There are certain impressions about learning a different language., that some languages seem easier and others are harder. None of that's really true; they're all difficult, and don't think otherwise. Everybody has their path in learning a language.

Let's talk about some of these theories of language acquisition. With respect to adults, mind you when I say ‘adults’, I’m saying anybody who has hit puberty and beyond. That has to do with the Critical Age Hypothesis; this is a hypothesis that is up for debate in some aspects, but not in others. It does seem to be the case that somewhere around puberty is when our brains have stopped absorbing like sponges. The elasticity and the neural plasticity are not the same when we are teenagers and adults as it is when we are children. Critical Age Hypothesis states that our brains don't seem to be able to pick up various skills as easily, including and especially language. It must be taught via logic, and if you think about a language course, that is really what you're learning: you're learning the logic of the language. Critical Age Hypothesis has its detractors; there are some that suggests that there is no such thing as waning elasticity of the neurons, that any person can learn any skill at any time, and there's no change or difference. That does not seem to be the case at least with respect to this concept of the Fundamental Difference Hypothesis, which states that learning a language as an adult is not at all like that of learning a language as a child. Regardless of the detractors, there is a large amount of data that show that with any major skill, children learn these skills as if through osmosis; they just watch, they practice, and they do, and it seems relatively effortless. The reality may not be the same, but that seems to be the case. As adults, the only time that is true is that if we can build upon a skill we already have; take language.

For example, I can learn a Romance language pretty easily, because I already have acquired and mastered two; based off of those two, I can use those skills to use to learn another Romance language. I will tell you that Germanic languages for me are very difficult; I'm terrible at learning Germanic languages. I just don't get the logic, despite the fact that I natively speak a Germanic language in English. It's because growing up, I didn't hear much in the way of Germanic languages; there was a Swedish family down the street, but they spoke English, and there was a Norwegian woman that one of my cousins married, but she spoke English, so realistically I didn't have much. I've tried to learn Japanese, and there's aspects of it that I get, but I heard Japanese as a kid by a few neighbors. Even though tonal languages seem to elude me as far as getting the tones down, I do see some of the patterns in them, but growing up, I had a number of friends who whose families were from Hong Kong, Shanghai, Beijing, or Taiwan. These are various places that speak different Sino-Tibetan languages, so for me, I start to see those patterns easier because I’ve been around them and have been exposed to them.

Fundamental Difference Hypothesis underlies mostly language learning, but, as I said, can be extended to other skill sets, especially motor skills. There's this concept with childhood development that when you expose a young child to as many inputs as possible—without overloading but certainly a number of them—and give them consistent access to those inputs, they pick up those talents and skills readily. That it sets up an affinity for those similar skills in their later lives. It's why we try to expose children to music, both listening and playing music from an early age, because if children are exposed to those skills early, they will continue to at least attempt to use them.

These two hypotheses are just that: they're hypotheses. We cannot officially make them into laws or universals, because there are exceptions always. In order to test them properly, we would need some very unethical training and activities, and we're not going to do that. We're not going to deprive a child linguistic input to see what can happen. We're not going to force them to do all sorts of activities that they may not be able to do physically. We're not going to do those things. We do have a goodly amount of evidence that shows that Critical Age Hypothesis does not say that you cannot learn a language once you hit puberty; it says that it must be taught as language acquisition based on logic. It can't be through osmosis.

There are certain common errors and processes that all adult language learners do. Whether they stay in this error-laden stage, or they get past these errors, this depends on a number of things. Fossilization is the big one; this is the situation of a language learner who keeps producing incorrect language in certain areas, but it's so ingrained in their mind that they just think it's the right way to do it. A couple of definitions: L2 and L1. ‘L’ refers to ‘language; ‘L2’ is the second language, while ‘L1’ is the first or native language. An example of a fossilization error: I teach Spanish, and one of the huge ones that I still get from intermediate students and beyond is, “Me llamo es." Spanish speakers, I apologize; I know how cringe worthy that is. "Me llamo es" is wrong in every way. "Me llamo" is 'I call myself'; it's what you say, when you say, “Oh, my name is Sarah,” you say "Me llamo Sarah;" I call myself Sarah. "Es" is a verb; it means 'is'. The problem is "llamo" is also a verb; it means 'I call', so "Me llamo es" is never going to work because you have two conjugated verbs that don't go together. It is a big error.

Interlanguage and interference are connected. Interlanguage is what we do as we're learning a language, when we combine elements to try and succeed in producing more of the target language. Think of telegraphic speech in child language acquisition, and this is kind of the adult version. Interlanguage is described as having more basic sentences that eventually lead to more complex sentences and phrases. We use interlanguage as we try to put our pieces together. Sometimes as we do that, we end up having interference or sometimes it's called transfer grammar. When your L1 interferes with your L2, for example as a native English speaker if I go to learn Russian, and I keep trying to use English phrasing, words, and pronunciation, instead of staying in Russian and learning the Russian, that's interference or transfer grammar. This is really common of all folks who learn a second language; we also see them children, but mostly we see this in adults.

Any language learner can get through all of this. In part, this is done through good instruction, which involves aspects that we're going to talk about soon: encouraging and open environments, like allowing students to feel like they can take a risk. Part of this is also internal motivation; we’ll talk about learner affect soon enough. But there are always going to be little bits that keep you from being a native speaker; we can be a near-native speaker, and I’ll explain more that in a minute, but some of those near-native elements are directly related to interference and the related to fossilization. But you can get around it.

I would be remiss to not talk about heritage learners. A heritage learner is somebody who is trying to learn the language of their heritage or ancestors; frequently it's the language of their parents or grandparents. Think of a case where you have a family that integrates to a new country, a new linguistic community. Their children and grandchildren may learn that new language very quickly, but then may drop the first language, the heritage language, along the way. Many folks, including maybe some of you, try to learn that heritage language in puberty or adulthood. This is a different process; it's not quite the same as learning from scratch. There are various levels of heritage learners. A low-level heritage learner knows the sounds and some words, but isn't really able to construct the basic sentence in that language. A mid-level or high-level heritage speaker can produce much more. There's always conflicting or competing issues going on with heritage learners, and they have to be addressed in the language and learning environment. There is frequently a desire to ‘speak properly’; I can't count the number of heritage Spanish speakers who sign up for first semester Spanish because they want to learn the language ‘properly’, thinking that what they know is not proper or accurate and somehow substandard. Frequently, that's not the case; in the vast majority of cases, that person is marginally, if not fully, fluent in that language. They just may need to boost their literacy, or learn more complex structures so that they can speak at a higher level, but they are fluent, at least at a basic level. There's also language attrition, which we talked a little bit about in child bilingualism. In many cases, once the heritage learner started their formal education in preschool or kindergarten, that is when they had to stop speaking their heritage language; they were forced into speaking the new language. As a result of societal pressures and everything else, they just ‘lose’ the first language; it's attrition. Just like a muscle that you stopped using and it atrophies, the same thing can be said for a ‘home language’ or heritage language.

Finally, there's this thing that I like to call ‘heritage speaker guilt’. As far as I know, this is a Sarah-ism; I don't know if this is an official term, but it's a specific kind of learner affect. When we are learning a new skill, including a new language, we suffer from some element of learner affect. That is the emotion that bubbles up inside of us and says that we can't do it, or we're scared to do it, or we're not confident in our abilities and we don't want to be made to feel the fool. When we're learning a language that does not have our heritage, you have learner affect in varying forms. But when it's part of your heritage, it's present at even higher levels, and it's a very specific one. There are a few flavors of it; there's the ‘why aren't I doing this correctly?’ or ‘why can't I get this right, why aren't I speaking properly?’ flavor. There's also the ‘why aren't I remembering this?’, ‘this was something I used to speak or hear when I was a child, why the heck can't I do it as an adult?’ flavor. (Frequently stronger language is used. 😉) Learner affect as a whole is an emotional block, and it takes some psychology to go past it, but it doubles down when it is your heritage language. I didn't have this problem as much when I learned Italian, because it was my great-grandparents that immigrated here and spoke it. But my mother was a different story; my mother, to this day, cannot learn Italian. It’s not to say she can't really learn it; she actually speaks Spanish, which she has not learned since high school many moons ago. If she goes to Mexico, she can give basic instructions to the taxi driver. That's Spanish, though; that's not Italian. She's got such a block on Italian. She has tried multiple times; first, she wanted me to teach her, which was a bad idea. (We have an amazing relationship, but learning from your child is a little bit different.) I suggested that she take classes at the community college or that she goes to the Italian Cultural Center in San Francisco. She tried a number of ways, and she's never been able to get over that heritage speaker guilt. In her mind, this should be instantaneous, and it's not.

How do you include heritage speakers? The answer is: whenever possible, especially the higher-level heritage speakers. We try to separate them out into their own class, and that makes sense; they're going to learn the language in a way that's different from a complete beginner. But the big one is support, even if you have a separate class, but especially if they're mixed in with the general population, as it were. You have to give them that emotional support, so they feel like they can take that risk, but also that they can feel pride in what they already know. You include their experiences, especially when discussing elements of culture. One of my favorite lessons when we do intermediate Spanish is when we talk about Spanish in the United States. I love this section, because we start picking apart this concept of what it means to be bicultural. There are so many folks in the class that are bicultural with different cultures, that it brings this really rich conversation. You start seeing the pride well up in them; that starts breaking down the learner affect, the heritage speaker guilt. Alongside that is to expand their knowledge. There are many people who say, “well, I don't need to learn the language; I’m already fluent in it, I already know everything about it.” Learning a language, especially a language that has multiple cultures and dialects—English, Spanish, and Mandarin are just three that come to mind—when you start expanding their horizons and cultural knowledge, they start feeling more of that pride. I always grew up with this pride of being an Italian-American. Even though I could count to 10 in our dialect and I knew words for certain food items, and certain not-so-nice things to say to people 😜. But when I was a senior in high school, I started taking Italian at a local community college. It expanded my horizons. Suddenly, I was learning about all sorts of things with respect to Italian culture, and not just my little neck of northwestern Italy, where my family is from. I suddenly was starting to learn about all these different concepts and different ways to phrase things. To this day, I still can't say focaccia, the bread, without visualizing the term; it still is always going to come out for me as fogassa, which is what we say in Lombardy. But I do know there's a difference, and I know that difference, and I express that difference. That all comes from learning about my heritage language and the cultures and the dialects that are associated with it.