13.1.8: Finding Sources

- Page ID

- 219175

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Describe strategies for beginning Internet research, including using Google Scholar

Beginning the Search

You probably shouldn’t start your research by just typing your research question into Google like, “What were medical practices like during the Battle of Gettysburg?” Instead, you should make use of key terms, or words that will appear frequently in the source.

To search key terms, think about important words that will occur in sources you could use. Then, type one or two of those terms into the search bar. Most search engines will generate results based on how frequently those words appear in articles and their abstracts. An abstract is a brief summary of a longer academic journal article.

Let’s use our topic of medical practices at the Battle of Gettysburg as an example. You might choose keywords like “amputation,” “field medicine,” and “Gettysburg.” This should yield articles that discuss amputations on the field during the Battle of Gettysburg. You could also search something like “anesthesia” and “Civil War,” which would lead you to articles about anesthetics during the war.

While searching with key terms, you may need to get creative. Some articles will use different language than you might expect, so try a variety of related terms to make sure you’re getting back all the possible results.

Suppose you are asked to write a paper in support of this assertion:

The proliferation of fast food has led to the national problem of obesity.

It’s not a good idea to type in the entire sentence in your search, as there are many irrelevant words in this search statement. Before typing, decide which words or phrases are essential to your search and which are non-essential. There are only two concepts in this statement that are essential to its meaning: fast food and obesity. You can eliminate the word “proliferation” because it modifies the essential concept of fast food and the phrase “national problem” is not crucial because we assume any article talking about “fast food” and “obesity” will discuss some negative aspects that would represent a national problem.

When you are researching on the web, search engines are effective tools for locating web pages relevant to your research, and they can save you time and frustration. However, for searches to yield the best results, you need a strategy and some basic knowledge of how search engines work. Without a clear search strategy, using a search engine is like wandering aimlessly in a field of corn looking for the perfect ear.

Click on the video below to learn more techniques for effective Internet searching.

https://lumenlearning.h5p.com/content/1290977906915703838/embed

Beginning your research with Google or another search engine is an easy way to quickly get an overview of your topic. Even more effective than Google Search is Google Advanced Search, and even better than that for academic resources is Google Scholar. Let’s consider Marvin’s experience.

Marvin, a college student at Any University, continues his discussion with the online professor about where to find sources.

Marvin: So can I just use Google or Bing to find sources?

O-Prof: Internet search engines can help you find sources, but they aren’t always the best route to getting to a good source. Try entering the search term “bottled water quality” into Google, without quotation marks around the term. How many hits do you get?

Marvin types it in.

Marvin: 94,000,000. That’s pretty much what I get whenever I do an Internet search. Too many results.

O-Prof: Which is one of the drawbacks of using only Internet search engines. The Internet may have cut down on the physical walking needed to find good sources, but it’s made up for the time savings by pointing you to more places than you could possibly go! But there are some ways you can narrow your search to get fewer, more focused results.

Marvin: Yeah, I know. Sometimes I add extra words in and it helps weed down the hits.

O-Prof: By combining search terms with certain words or symbols, you can control what the search engine looks for. If you put more than one term into a Google search box, the search engine will only give you sites that include both terms, since it uses the Boolean operator AND as the default for its searches. If you put OR between two search terms, you’ll end up getting even more results, because Google will look for all websites containing either of the terms. Using a minus sign in front of a term eliminates things you’re not interested in. It’s the Google equivalent of the Boolean operator NOT. Try entering bottled water quality health -teeth.

Marvin types in the words, remembering suddenly that he has to make an appointment with the dentist.

Marvin: 42,000,000 hits.

O-Prof: Still a lot. You can also put quotation marks around groups of words and the search engine will look only for sites that contain all of those words in the exact order you’ve given. And you can combine this strategy with the other ways of limiting your search. Try “bottled water quality” (in quotation marks) health -teeth.

Marvin: 950,000. That’s a little better.

O-Prof: Now try adding what type of website you are looking for, maybe a .gov or an .edu. Try typing “bottled water quality” heath -teeth site:.edu

Marvin: Okay, under 17,000 results now.

O-Prof: Yes, a definite improvement. Sometimes you want to be careful though not to narrow it so far that you miss useful sources. You have to play around with your search terms to get to what you need. A bigger problem with Internet search engines, though, is that they won’t necessarily lead you to the sources considered most valuable for college writing.

Marvin: My professor said something about using peer-reviewed articles in scholarly journals.

O-Prof: Professors will often want you to use such sources. Articles in scholarly journals are written by experts; and if a journal’s peer-reviewed, its articles have been screened by other experts (the authors’ peers) before being published.

Marvin: So that would make peer-reviewed articles pretty reliable. Where do I find them?

O-Prof: Google’s got a specialized search engine, Google Scholar, that will search for scholarly articles that might be useful. But often the best place is the college library’s bibliographic databases.

To be continued. . .

Google Scholar

Google Scholar is Google’s academic search engine that searches across scholarly literature. It has extensive coverage, retrieving information from academic publishers, professional organizations, university repositories, professional websites, and government websites.

The benefits of searching within Google Scholar are numerous, but a search solely using Google Scholar will be insufficient for your research. Consider the following benefits of Google Scholar and library databases.

| Google Scholar benefits | Library Databases benefits |

Contributors and AttributionsCC licensed content, Shared previously

|

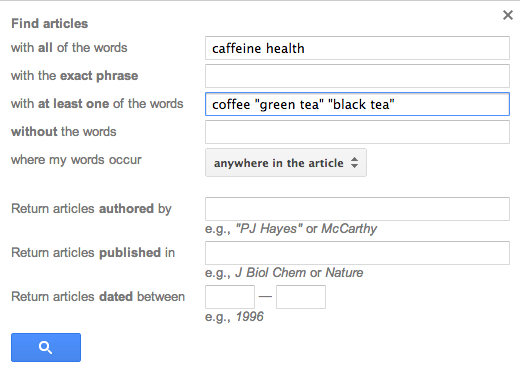

Figure 1. The advanced search features of Google Scholar.

Figure 1. The advanced search features of Google Scholar.