11.1: Homo heidelbergensis

- Page ID

- 62356

For many years, fossil material from ~500–200 kya from Africa, Asia, and Europe that was more human- or sapiens-like was included in our own genus and species but was distinguished as “Early Archaic” Homo sapiens (EAHS). There was much debate as to when to draw the line between more erectus-like forms and more sapiens-like forms. The prevailing view was that material on all three continents was descended from H. erectus. (The various geographic species distinctions for H. erectus had not yet come into use.)

There are two traditional models about the origins of humans. The first is the Regional Continuity Model (RCM). In this scenario, erectus-like forms on each of the continents slowly evolved into modern humans via gene flow between populations. This is in contrast to the second theory of Recent African Origin (RAO) model, whereby modern humans evolved in Africa and moved out to eventually replace archaic forms elsewhere, e.g. H. erectus in Asia.

The RAO model has gained in popularity due to a combination of the reevaluation of fossil material and especially DNA methods aimed at evaluating genetic distance between species, in terms of number of years since divergence from a common ancestor. The material from Asia that had previously been assigned to EAHS has been relegated to H. erectus, with very little evidence for an intermediate form bridging the gap between H. erectus and anatomically modern humans (AMH) (see below).

However, new mapping of the Neanderthal genome shows an overlap of 1-4% of DNA in humans and Neanderthals, which is direct evidence of interbreeding between the two. Because of this, a new model, called the Assimilation Model, is being proposed to merge the correct information from RCM and RAO (Etheridge-Criswell, 2018).

Fossil material from Europe and Africa that was formerly assigned to EAHS is now termed Homo heidelbergensis. It is now well accepted that H. heidelbergensis was ancestral to both humans and Neanderthals.

Mandibles from Tighenif are very similar to the type specimen, the Mauer mandible (see Figure) from the Heidelberg area of Germany, from which the species name is derived. In addition to the material from North Africa, the oldest material is from the Bodo site in Ethiopia, dated to 600 kya. Thus while an African origin is favored, some believe that H. heidelbergensis is descended from a species in Europe. Whether H. heidelbergensis evolved in Europe or Africa, they had to have migrated from one continent to the other.

In addition, a new species of hominin is also thought to be descended from H. heidelbergensis. The Denisovans, as they have come to be known due to their discovery in the Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains of Russia, are thought to have branched off from the H. heidelbergensis lineage that led to Neanderthals (see below). DNA analyses show that Denisovans interbred with Neanderthals, as well as the first wave of AMH that left Africa, possibly around 125 kya and subsequently settled Melanesia and Australia.

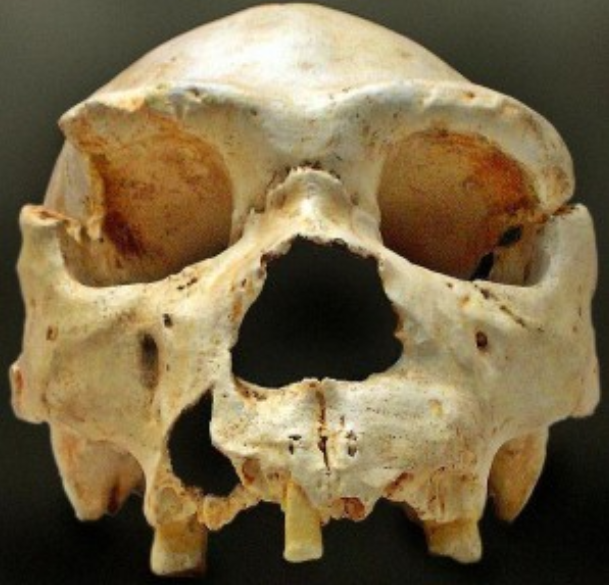

The earliest discoveries of H. heidelbergensis are from Germany. The type specimen was discovered in 1907 in Mauer, Germany. The oldest site is Bodo, Ethiopia (600 kya). There are numerous H. heidelbergensis sites in Europe (e.g. Steinheim, see Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)) that date from as early as 500 kya and range from Spain through Eastern Europe. The greatest number of individuals came from the Sima de los Huesos (“Pit of Bones”) (see Figure) site in the Atapuerca Mountains of Spain.

Anatomy

H. heidelbergensis is primarily distinguished from erectus-like forms by its increased cranial capacity (1100–1400 cc—93% that of AMH) and more modern skull vault. Cerebral expansion, especially of the parietal lobes, led to increased cranial breadth in the superior aspect of the skull vault and thus a more vertically oriented skull. The occipital region is less angular due to reduced robusticity in the nuchal musculature. Some specimens have very pronounced brow ridges, and some have speculated that those individuals represent males of the species. Like those species that preceded them, H. heidelbergensis were mobile foragers. They left evidence for both seasonal and differential use camps. In addition to using rock shelters and caves for shelter, they are the first species for which we have evidence of building free-standing structures. At the site of Terra Amata in the south of France, the living floors of free-standing structures have been excavated. It is thought that a group returned to the site annually for fishing and other subsistence activities and reconstructed their huts (up to 11 times) on the exact same site.

Tools

They are credited as having been the first to make the tools necessary for efficient fishing. Like past species, their big-game hunting capabilities are questionable. However, there is evidence that they may have ambushed large animals by forcing them off cliffs or cornering them in dead-end canyons. Support for ambush comes from faunal assemblages on the Channel Islands off the coast of France. The remains are from animals in prime condition, and the frequency of the various bones shows that the hominins were differentially removing the limbs and bringing them back to butcher at a home base.

The species is credited with inventing a more conservative method, termed the Levallois technique, for controlling flake shape and maximizing their yield from a core. Flakes could then be worked into a variety of tools. They could also shape the core in such a way that a point could be struck off that was sharp on all sides (see Figure). H. heidelbergensis were the first to make compound tools, i.e. tools with more than one component, such as hammers and stone-tipped spears.

Culture/Behavior

H. heidelbergensis is the first species for which there is ample evidence of the controlled use of fire, in that hearths have been found at several sites. In addition to the aforementioned inventions, a couple of novel cultural practices have been suggested for the species. They may have made and used furniture, such as seaweed beds and stone blocks, and there is some evidence of art or written communication in the form of arcs and angles and the use of ocher (mineral pigments).

A fine pink quartz hand axe, nicknamed “Excalibur,” was found among the bodies in the “Pit of Bones.” Some researchers believe it is the earliest evidence of ritual associated with burial, in that the artifact was seemingly unused and manufactured from exotic stone. The seclusion of the bodies may also represent an attempt at keeping them from being ravaged by scavengers.

All of these advancements and innovations are unequivocal support for the increase in cognition that resulted from the degree of encephalization and changes in brain architecture that are evident in the skull size and shape of H. heidelbergensis. Finally, if the new DNA evidence is correct and H. heidelbergensis branched off from our ancestry versus being our ancestor, the behavioral and cultural complexity apparent at H. heidelbergensis sites indicates that our common ancestor was cognitively advanced more than 800 kya!