7.1: Confirming and Disconfirming Climates

- Page ID

- 55230

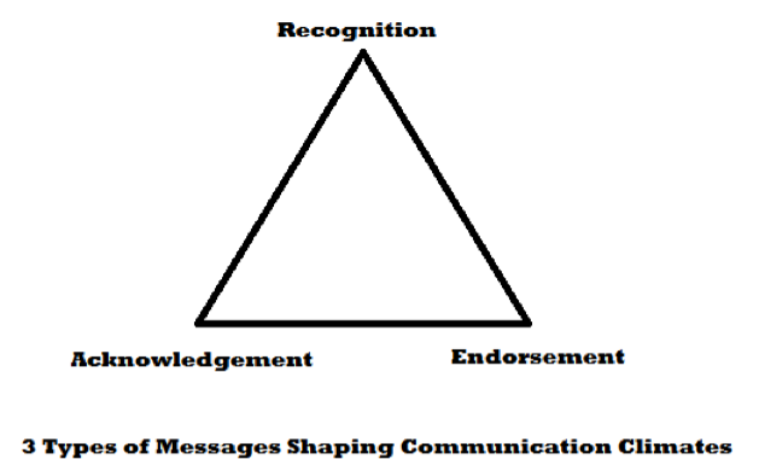

Positive and negative climates can be understood along three dimensions—recognition, acknowledgement, and endorsement. We experience Confirming Climates when we receive messages that demonstrate our value and worth from those with whom we have a relationship. Conversely, we experience Disconfirming Climates when we receive messages that suggest we are devalued and unimportant. Obviously, most of us like to be in confirming climates because they foster emotional safety as well as personal and relational growth. However, it is likely that your relationships fall somewhere between the two extremes. Let’s look at three types of messages that create confirming and disconfirming climates.

Recognition Messages: Recognition messages either confirm or deny another person’s existence. For example, if a friend enters your home and you smile, hug him, and say, “I’m so glad to see you” you are confirming his existence. If you say “good morning” to a colleague and she ignores you by walking out of the room without saying anything, she is creating a disconfirming climate by not recognizing you as a unique individual.

Acknowledgement Messages: Acknowledgement messages go beyond recognizing another’s existence by confirming what they say or how they feel. Nodding our head while listening, or laughing appropriately at a funny story, are nonverbal acknowledgement messages. When a friend tells you she had a really bad day at work and you respond with, “Yeah, that does sound hard, do you want to go somewhere quiet and talk?” you are acknowledging and responding to her feelings. In contrast, if you were to respond to your friend’s frustrations with a comment like, “That’s nothing. Listen to what happened to me today,” you would be ignoring her experience and presenting yours as more important.

Figure 1

Endorsement Messages: Endorsement messages go one step further by recognizing a person’s feelings as valid. Suppose a friend comes to you upset after a fight with his girlfriend. If you respond with, “Yeah, I can see why you would be upset” you are endorsing his right to feel upset. However, if you said, “Get over it. At least you have a girlfriend” you would be sending messages that deny his right to feel frustrated in that moment. While it is difficult to see people we care about in emotional pain, people are responsible for their own emotions. When we let people own their emotions and do not tell them how to feel, we are creating supportive climates that provide a safe environment for them to work through their problems.

Thinking about Conflict

When you hear the word “conflict,” do you have a positive or negative reaction? Are you someone who thinks conflict should be avoided at all costs? While conflict may be uncomfortable and challenging it doesn’t have to be negative. Think about the social and political changes that came about from the conflict of the civil rights movement during the 1960’s. There is no doubt that this conflict was painful and even deadly for some civil rights activists, but the conflict resulted in the elimination of many discriminatory practices and helped create a more egalitarian social system in the United States. Let’s look at two distinct orientations to conflict, as well as options for how to respond to conflict in our interpersonal relationships.

Figure 2

Conflict as Destructive

When we shy away from conflict in our interpersonal relationships we may do so because we conceptualize it as destructive to our relationships. As with many of our beliefs and attitudes, they are not always well-grounded and lead to destructive behaviors. Augsburger outlined four assumptions of viewing conflict as destructive:

- Conflict is a destructive disturbance of the peace.

- The social system should not be adjusted to meet the needs of members; rather, members should adapt to the established values.

- Confrontations are destructive and ineffective.

- Disputants should be punished.

When we view conflict this way, we believe that it is a threat to the established order of the relationship. Think about sports as an analogy of how we view conflict as destructive. In the U.S. we like sports that have winners and losers. Sports and games where a tie is an option often seem confusing to us. How can neither team win or lose? When we apply this to our relationships, it’s understandable why we would be resistant to engaging in conflict. I don’t want to lose, and I don’t want to see my relational partner lose. So, an option is to avoid conflict so that neither person has to face that result.

Conflict as Productive

In contrast to seeing conflict as destructive, also possible, even healthy, is to view conflict as a productive natural outgrowth and component of human relationships. Augsburger described four assumptions of viewing conflict as productive:

- Conflict is a normal, useful process.

- All issues are subject to change through negotiation.

- Direct confrontation and conciliation are valued.

- Conflict is a necessary renegotiation of an implied contract—a redistribution of opportunity, release of tensions, and renewal of relationships.

From this perspective, conflict provides an opportunity for strengthening relationships, not harming them. Conflict is a chance for relational partners to find ways to meet the needs of one another, even when these needs conflict. Think back to our discussion of dialectical tensions. While you may not explicitly argue with your relational partners about these tensions, the fact that you are negotiating them points to your ability to use conflict in productive ways for the relationship as a whole, and the needs of the individuals in the relationship.

Types of Conflict

Understanding the different ways of valuing conflict is a first step toward engaging in productive conflict interactions. Likewise, knowing the various types of conflict that occur in interpersonal relationships also helps us to identify appropriate strategies for managing certain types of conflict. Cole states that there are five types of conflict in interpersonal relationships: Affective, Conflict of Interest, Value, Cognitive, and Goal.

Affective conflict. Affective conflict arises when we have incompatible feelings with another person. For example, if a couple has been dating for a while, one of the partners may want to marry as a sign of love while the other decides they want to see other people. What do they do? The differences in feelings for one another are the source of affective conflict.

Conflict of Interest. This type of conflict arises when people disagree about a plan of action or what to do in a given circumstance. For example, Julie, a Christian Scientist, does not believe in seeking medical intervention, but believes that prayer can cure illness. Jeff, a Catholic, does believe in seeking conventional medical attention as treatment for illness. What happens when Julie and Jeff decide to have children? Do they honor Jeff’s beliefs and take the kids to the doctor when they are ill, or respect and practice Julie’s religion? This is a conflict of interest.

Value Conflict. A difference in ideologies or values between relational partners is called value conflict. In the example of Julie and Jeff, a conflict of interest about what to do concerning their children’s medical needs results from differing religious values. Many people engage in conflict about religion and politics. Remember the old saying, “Never talk about religion and politics with your family.”

Cognitive Conflict

Cognitive conflict is the difference in thought process, interpretation of events, and perceptions. Marsha and Victoria, a long-term couple, are both invited to a party. Victoria declines because she has a big presentation at work the next morning and wants to be well rested. At the party, their mutual friends Michael and Lisa notice Marsha spending the entire evening with Karen. Lisa suspects Marsha may be flirting and cheating on Victoria, but Michael disagrees and says Marsha and Karen are just close friends catching up. Michael and Lisa are observing the same interaction but have a disagreement about what it means. This is an example of cognitive conflict.

Goal Conflict

Goal conflict occurs when people disagree about a final outcome. Jesse and Maria are getting ready to buy their first house. Maria wants something that has long-term investment potential while Jesse wants a house to suit their needs for a few years and then plans to move into a larger house. Maria has long-term goals for the house purchase and Jesse is thinking in more immediate terms. These two have two different goals in regards to purchasing a home.

Strategies for Managing Conflict

When we ask our students what they want to do when they experience conflict, most of the time they say “resolve it.” While this is understandable, also important to understand is that conflict is ongoing in all relationships, and our approach to conflict should be to “manage it” instead of always trying to “resolve it.”

One way to understand options for managing conflict is by knowing five major strategies for managing conflict in relationships. While most of us probably favor one strategy over another, we all have multiple options for managing conflict in our relationships. Having a variety of options available gives us flexibility in our interactions with others. Five strategies for managing interpersonal conflict include dominating, integrating, compromising, obliging, and avoiding (Rahim; Rahim & Magner; Thomas & Kilmann). One way to think about these strategies, and your decision to select one over another, is to think about whose needs will be met in the conflict situation. You can conceptualize this idea according to the degree of concern for the self and the degree of concern for others.

When people select the dominating strategy, or win-lose approach, they exhibit high concern for the self and low concern for the other person. The goal here is to win the conflict. This approach is often characterized by loud, forceful, and interrupting communication. Again, this is analogous to sports. Too often, we avoid conflict because we believe the only other alternative is to try to dominate the other person. In relationships where we care about others, it’s no wonder this strategy can seem unappealing.

The obliging style shows a moderate degree of concern for self and others, and a high degree of concern for the relationship itself. In this approach, the individuals are less important than the relationship as a whole. Here, a person may minimize the differences or a specific issue in order to emphasize the commonalities. The comment, “The fact that we disagree about politics isn’t a big deal since we share the same ethical and moral beliefs,” exemplifies an obliging style.

The compromising style is evident when both parties are willing to give up something in order to gain something else. When environmental activist, Julia Butterfly Hill agreed to end her two-year long tree sit in Luna as a protest against the logging practices of Pacific Lumber Company (PALCO), and pay them $50,000 in exchange for their promise to protect Luna and not cut within a 20-foot buffer zone, she and PALCO reached a compromise. If one of the parties feels the compromise is unequal they may be less likely to stick to it long term. When conflict is unavoidable, many times people will opt for compromise. One of the problems with compromise is that neither party fully gets their needs met. If you want Mexican food and your friend wants pizza, you might agree to compromise and go someplace that serves Mexican pizza. While this may seem like a good idea, you may have really been craving a burrito and your friend may have really been craving a pepperoni pizza. In this case, while the compromise brought together two food genres, neither person got their desire met.

When one avoids a conflict they may suppress feelings of frustration or walk away from a situation. While this is often regarded as expressing a low concern for self and others because problems are not dealt with, the opposite may be true in some contexts. Take, for example, a heated argument between Ginny and Pat. Pat is about to make a hurtful remark out of frustration. Instead, she decides that she needs to avoid this argument right now until she and Ginny can come back and discuss things in a more calm fashion. In this case, temporarily avoiding the conflict can be beneficial. However, conflict avoidance over the long term generally has negative consequences for a relationship because neither person is willing to participate in the conflict management process.

Finally, integrating demonstrates a high level of concern for both self and others. Using this strategy, individuals agree to share information, feelings, and creativity to try to reach a mutually acceptable solution that meets both of their needs. In our food example above, one strategy would be for both people to get the food they want, then take it on a picnic in the park. This way, both people are getting their needs met fully, and in a way that extends beyond original notions of win-lose approaches for managing the conflict. The downside to this strategy is that it is very time consuming and requires high levels of trust.

Key Terms

- Communication Climate

- Confirming Climate

- Disconfirming Climate

- Recognition Messages

- Acknowledgement Messages

- Endorsement Messages

- Affective Conflict

- Conflict of Interest

- Value Conflict

- Cognitive Conflict

- Goal Conflict

- Dominating Strategy

- Obliging Style

- Compromising Style

- Avoids

- Integrating

References

- Image by Spaynton is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

- Image by JESHOOTS.COM on Unsplash