9.3: Whiteness- White Privilege, White Supremacy, and White Fragility

- Page ID

- 196262

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Whiteness vs. the Other

Whiteness is something that was created by juxtaposing Europeans with Native peoples and other non-Europeans. Michael Omi and Howard Winant (2014) define racial formation as the process in which racial identity is created and experienced. Non-Europeans were "othered" in order to maintain a superiority of whiteness. Since encountering Native peoples in the 15th and 16th centuries in what is now the United States, white settlers used to judge Native peoples’ appearances as backwards with "dark devil skin," even as sexually loose and therefore immoral. Relatedly, white settlers would see Africans as dark and therefore opposite of them, having protruding lips and often created caricatures with images of dark people with huge lips. In both instances, white settlers saw these peoples as “heathen” and “uncivilized” and therefore used this to justify why they needed to conquer Native lands and enslave Black people, as both were seen as unfit to take care of themselves. This idea of "unfit to take care of themselves" was promoted through an infantilization of nonwhites meaning they were described as childlike and therefore unable to take care of themselves (see Takaki, 2008 or Zinn, 2009, or others for more information about these initial racializations). The sidebar below shows an example of infantilization that was extended to relate to other people and serve as justification for conquest and rule, just like it had been used against Native Americans and Black Americans. Something identified as racial, whether having direct association to a racial group, whether true or not or even something like having a motive to designate something racially, is what Omi and Winant (2014) call racial projects. In defining racism, they state that racial projects can be defined as racist if “it creates or reproduces structures of domination based on racial signification and identities” (Omi and Winant, 2014, p. 128). In this way, the combination of racial association or label with “structures of domination” can mean that racism requires a notion of superiority tied to a particular group.

The Three I’s of Oppression

The three I’s of oppression describes multi-dimensional domination.

Interpersonal oppression is when someone is being oppressed by another person, thus inter + personal. Violently attacking someone on the street is a form of interpersonal oppression. Attacking someone specifically due to race is interpersonal racism. Name-calling, microaggressions, verbal insults, and verbal or physical assaults, are some examples which demonstrate interactive exchange within interpersonal oppression. Microaggressions have increasingly been researched amongst people of color communities as a way to explain oppression that isn’t always considered a “macro” oppression like institutional racism but something usually more interpersonal and “less severe” like a verbal insult or slights. Filipino American psychologist Kevin Nadal is one who has lead research on microaggressions against Filipinx Americans specifically, and Asian Americans generally. With Asian Americans, one thing that some expressed was treating Asian Americans as foreigners as if many hadn’t been born here. Many say that even though they are called “micro”aggressions, they can still cause deep psychological impact especially when experienced constantly and that they can often feel larger than “micro” in impact. While seemingly disconnected, interpersonal oppression or racism can largely be in relationship to the Institutional. Because of the policies that frame how to operate with people, individuals can treat one another according to certain laws and procedures.

Internalized oppression is when a person internalizes negative messages, stereotypes, etc. that are associated with some aspect of them. For example, if they are a person of color and hate their skin color or hair texture, this could represent internalized racism that they somehow learned in their lifetime. Colonial mentality is when one believes in the inferiority of colonized peoples or the inferiority of some aspect within being a colonized or formerly colonized people. One example of this is if an English-speaking country colonized another country and colonizers teach them that English is superior, then believing that English is better than their language(s) in part shows that this colonial mentality accepts the superiority of the colonizer. Even though institutional and interpersonal oppression seem to be the most damaging and harmful of the oppressions, decolonial scholars importantly point out the extreme dangers of internalized oppression. When a person believes themselves to be inferior, this contributes to their continual subjugation and oppression as not believing they have power and agency. When people absorb ideas and beliefs of a group, they will perpetuate or challenge these ideas in regard to themselves, their family, and others. This helps to complete the cycle between the I’s.

Institutional oppression (detailed later in this chapter) is oppression within organizations, societal institutions such as government, health, media, schooling, and more. According to Omi and Winant (2015), institutional oppression is one that is largely seen through laws, policies, and protocols. In this way, institutions function largely without needing constant surveillance that guides every movement because when rules are created, people for the most part will follow them. Institutions also operate seemingly invisibly in this way by standardizing functions and symbols so that they are universally known. Institutional oppression within laws can exclude people from immigrating to the United States and it can also decide who is criminalized or otherwise different. The Immigration Act of 1924, for example, placed quotas on immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe and completely denied immigrants from Asia.

In the 1970s, education scholar Caroline Persell named the three I’s of oppression and included societal oppression to be in a system called the “structures of dominance” that worked together to uphold oppressive ideologies in a cycle. Societal oppression are the societal values and beliefs, or ideologies, that can serve to uphold dominance for some and subordination for others. In her model of structures of dominance, institutions shape the way that people interact with one another, and therefore impacts how one sees themselves. This then translates into group values and beliefs. She specifically uses this model for education in the way that educational policy and rules impact teacher-to-student behavior and student-to-teacher behavior, and counselor-to-student behavior, etc. Then this influences the way the students see themselves, the way teachers see themselves, etc. and gets absorbed into existing and new pathways for societal beliefs. There are more ways that oppression operates within the dimensions according to Persell’s structures of dominance, but one of the most significant of her ideas within this model reflect how structures of dominance don’t just self-maintain oppression, but in particular it upholds the domination of the ruling class within education and throughout society.

Race and Children

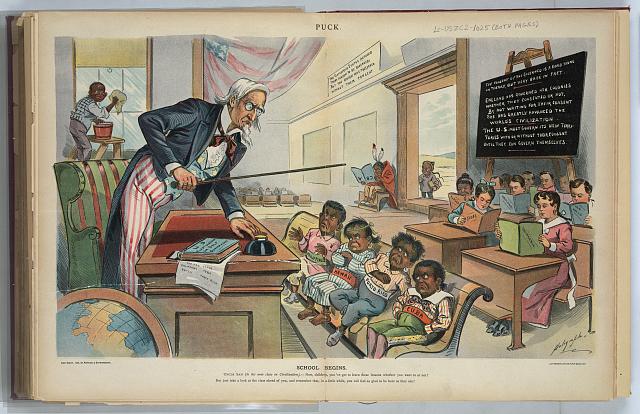

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): School begins / Dalrymple, 1899. (Public Domain; Louis Dalrymple via Library of Congress)

Figure 9.3.1 from the Library Congress, school children are deemed savages and Uncle Sam is teaching the class. It portrays different places such as Cuba, Philippines, Guam, Puerto Rico, etc. as childlike and unruly. This picture is used to show how these places need the care and guidance of the United States through direct policy and governance. Specifically, these places became a part of U.S. territory in 1898 after the Spanish-American War, and as the U.S. exercised dominance through narratives of saviorism, or the idea that these places need the U.S. to “save” them from their uncivilized and unfit-to-rule selves. The authors of The Forbidden Book: The Philippine-American War in Political Cartoons (2014) gathered some of these images as a look at U.S. imperialism, or rule that extends over an empire and dictates matters of economic, political, social, cultural rules of another country. Hawai'i is included in this and actually became a state but many are unaware that the U.S. imprisoned Queen Liliʻuokalani of Hawaiʻi in her home and forcefully took over Hawaiʻi so that’s how it became a state. Many sovereignty activists are legally battling the mainstream depiction of Hawaiʻi annexation narratives that exclude the violent takeover of their lands and are imprisoned. Scholar Noenoe Silva discusses how the Queen of Hawaiʻi was compared to Black Americans and deemed unfit the rule. The U.S. created caricatures of her that likened her to racist Black caricatures. These images of imperialism gathered in The Forbidden Book shows the long history of "othering" and conquest that links Black, Indigenous, and people of color histories and realities and help to unmask hidden truths about race, U.S. imperialism, and white supremacy.

Scholar Robin Bernstein wrote a book on race and childhood where she demonstrates how white children are seen as more racially innocent than Black children. This is evident in children’s toys and especially dolls where white dolls have had angelic appearances with rosy cheeks, delicate curly blond tendrils, and blue eyes. Bernstein illustrates how this innocence is not just one that displays so-called innocent appearances, but also defines the way that we understand whiteness and blackness especially in this age. This is especially significant because there is often a regard for treating race and racism as “very political” and “inappropriate” for younger ages. The idea of racial innocence as non-political attempts to lay personal blame on people of color for any discrimination or oppression instead and deflects from structural causes. De-politicizing race and feigning a non-connection to innocence reinforces attempts to deny discussing race with children. A common sentiment is the desire to not want to teach children about race because they are perceived as young and impressionable. This misconception actually obscures the fact that children can experience racism at a really young age and as discussed about the doll test below, they can distinguish at an early age as well.

Ideology and Hegemony

Ideology is a set of beliefs such as within a group. Ideologies are a part of all societies and contribute to how they define and distinguish who they are. Ideologies are often used to delineate who belongs and who does not, by sometimes attempting to require members of society and groups to practice and embrace such beliefs. In Ethnic Studies, it is recognized how sometimes ideologies spouted by elitist members in society can be harmful to the rest of the population, especially when they disregard the humanity of others, devalue their labor and cultures, and attempt to erase other cultures and way of life.

One example of ideology is whiteness as the standard for beauty

.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1.7}\): "Then and Now® Bathing Suit Barbie® - Made in China". (CC by NC-ND 4.0; Dolls N' Stuff via Flickr)

Related to ideology, hegemony is the dominance of one groups’ beliefs over others. When dominating beliefs are the standard or norm within organizations and institutions, it then establishes power for the dominant group and therefore helps to solidify dominant practices and beliefs within laws and policies that then are applied to everyone. Antonio Gramsci first introduced the concept of hegemony as cultural hegemony to explain the structured domination/subordination relationship. For example, Bates (1975) remarked how Gramsciʻs hegemony could “eliminate class struggle” by squashing it with such dominant norms and beliefs (p. 351). These laws and policies that uphold dominant beliefs as the norm often oppress marginalized populations.

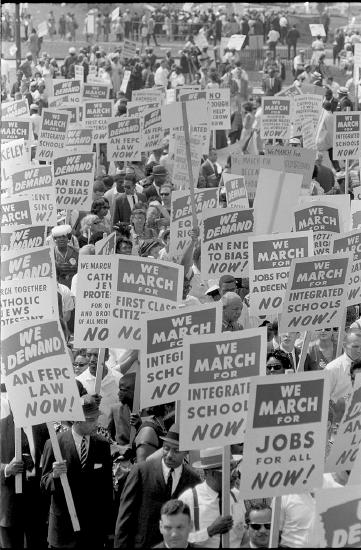

Dr. Kenneth Clark and Mamie Phipps Clark were influential African American psychologists known for their pioneering research on racial segregation and its impact on children's self-esteem and identity. Their famous "doll tests" in the 1940s provided empirical evidence of the psychological harm caused by racial segregation, as African American children often preferred white dolls over black dolls, revealing the internalized prejudice and negative self-perception imposed by segregation. This research played a crucial role in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case, which led to the desegregation of American schools in 1954, as it demonstrated the harmful effects of racial discrimination on young minds and underscored the need for change in educational policies and practices. The Clarks' work contributed significantly to the civil rights movement and continues to be influential in the fields of psychology and education.

Dr. Kenneth Clark and Mamie Phipps Clark were influential African American psychologists known for their pioneering research on racial segregation and its impact on children's self-esteem and identity. Their famous "doll tests" in the 1940s provided empirical evidence of the psychological harm caused by racial segregation, as African American children often preferred white dolls over black dolls, revealing the internalized prejudice and negative self-perception imposed by segregation. This research played a crucial role in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case, which led to the desegregation of American schools in 1954, as it demonstrated the harmful effects of racial discrimination on young minds and underscored the need for change in educational policies and practices. The Clarks' work contributed significantly to the civil rights movement and continues to be influential in the fields of psychology and education.

In the doll test white and Black children were shown dolls, identical except for color, and were asked various questions about the dolls to test their racial perceptions. The questions included “what doll was the bad doll?” or “what doll is the pretty doll?” while being shown the Black and white doll. Many times the children associated being bad, inferior, and ugly with the Black doll and being good, beautiful, and smart with the white doll. For many, it can be astonishing to witness the choices being made especially when the skin color of the dolls being seen as negative is often the same skin color as the child.

The doll test was only one part of Dr. Clark’s testimony in Brown vs. Board – it did not constitute the largest portion of his analysis and expert report. His conclusions during his testimony were based on a comprehensive analysis of the most cutting-edge psychology scholarship of the period.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): "Doll Test, Harlem, New York" by Gordon Parks, Minneapolis Institute of Art is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Racialization

Racialization is assigning a racial category to someone especially that has not had a designation before (Omi and Winant, 2014). This typically refers to the way that people were categorized historically such as laws that dictated who can identify as white. In a general sense, racialization is designating a race to someone even if it is a different designation from what they actually identify themselves as or a different designation from what someone else has told them. For example, people might racialize mixed race people differently if they are deemed racially ambiguous. People may also racialize people based on their own contexts. For example, if someone has dark skin and curly hair and they’re walking around New York City, one might automatically think the person is Dominican due to the presence of Dominican people in New York City that might have dark skin and curly hair. This means that their context, or the conditions around them, influence how they racialize others. Even when someone or a group is racialized by others, not only does it mean that a lot of times such signification is not accepted by the individual or group, but that such characterization of a racial group is often forced onto minoritized groups.

Since colonization, U.S. nationality has been marked as one who is white. In Ronald Takaki’s opening chapter of A Different Mirror (2008), he recalls how his midwestern taxi driver sees his Asianness as foreign despite Takaki being born in the U.S. The taxi driver reveled at his remarkable English skills. This is one example of how white is seen as “American.” Takaki discusses this phenomenon as a master narrative that says nonwhite is foreign and does not belong. The prevalent belief in this master narrative or metanarrative also contributes to promoting the U.S. flag as super patriotic and representing traditional ideals and values that counter multiculturalism and other progress such as within gender, sexuality, and class struggles. When there is a metanarrative that “American” is limited to white, it creates a standard for legislation that uphold rights for those who promote these values.

Normalization of Whiteness and Color-Blind Racism

The normalization of whiteness helps to create a standardization of whiteness. As discussed on the next page, #oscarssowhite was used to point out how the Academy Awards showcases white actors and actresses way more than nonwhites. The normalization of whiteness helps the standardization of whiteness because when whiteness is normalized, it is held with greater esteem and therefore becomes the “standard” in which all must strive toward.

White Privilege

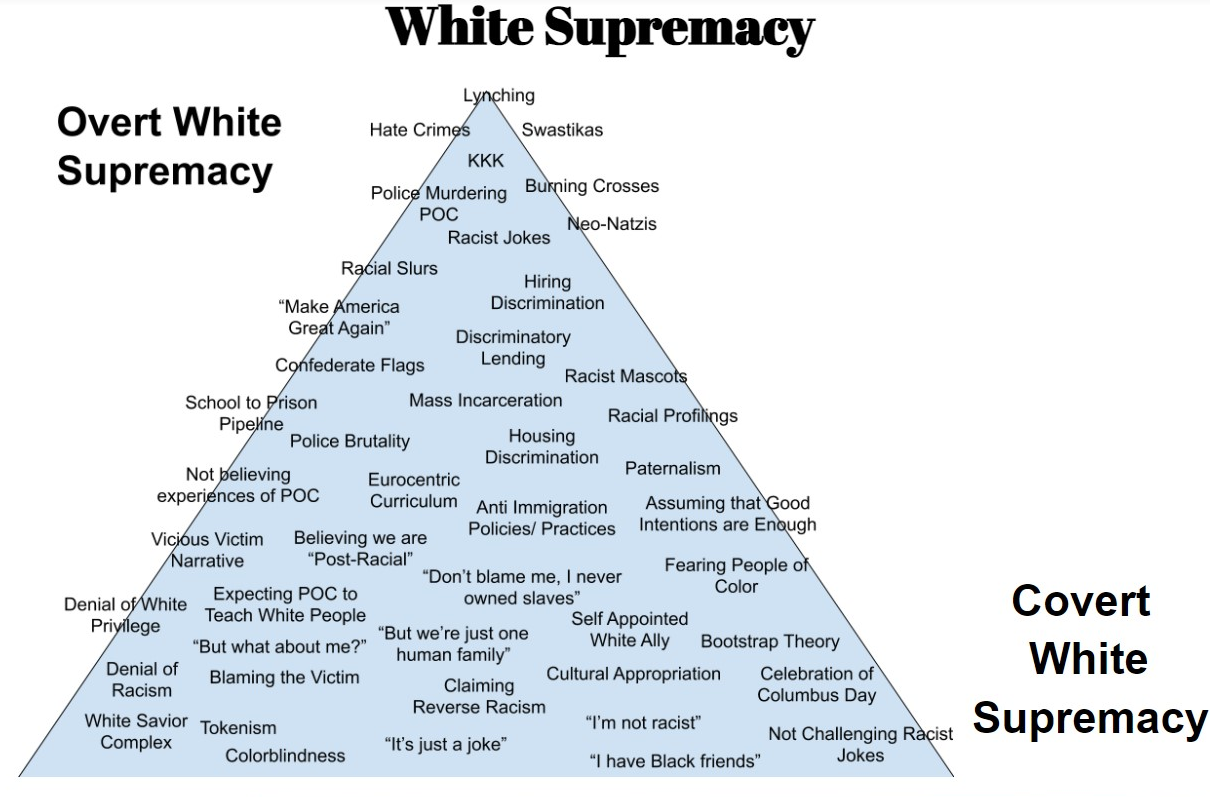

White Supremacy

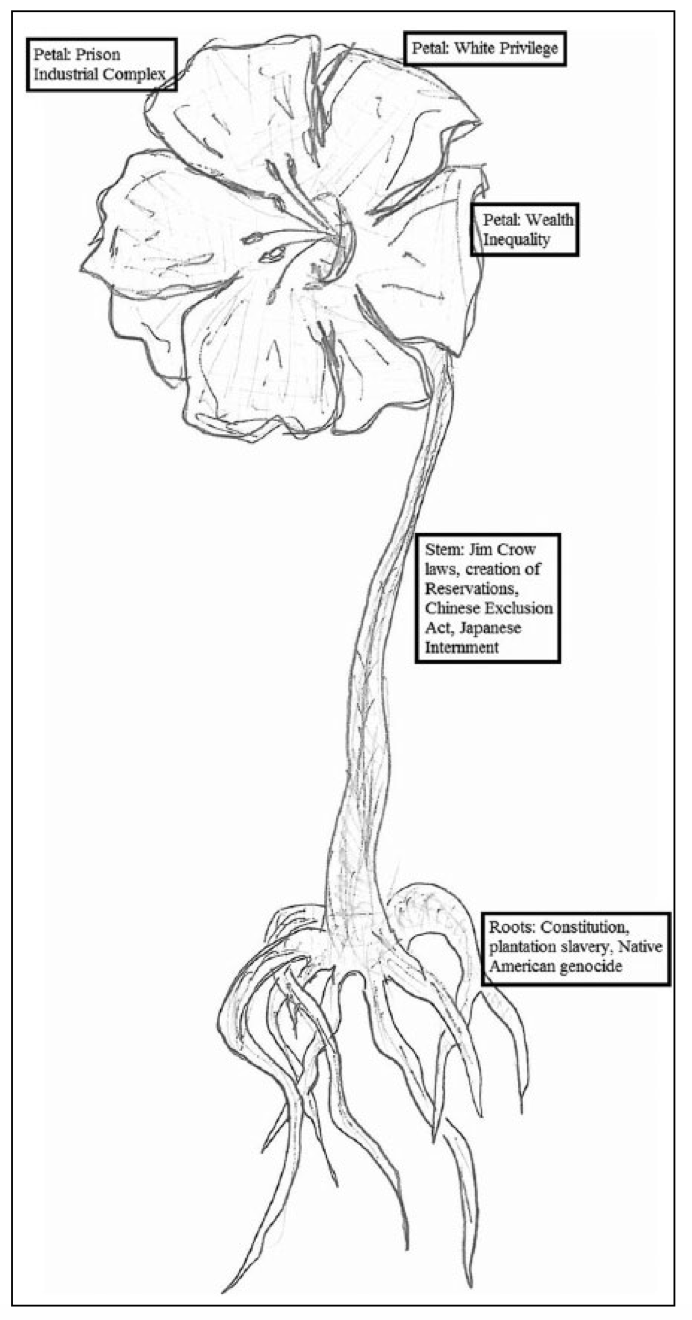

Scholar, activist, Chicana feminist Elizabeth Martinez explicitly defines white supremacy as a system that promotes privilege and power of whiteness for white people through institutional entities (see: What is White Supremacy by Elizabeth ‘Betita’ Martinez). White supremacy is rooted in African enslavement, Native American removal and genocide, imperialism and war in Asia, and land dispossession of Mexico. These linkages to various non-European groups in these historical ways is not uncommon knowledge amongst Ethnic Studies scholars. Martinez distinguishes white supremacy from the term "racism," because white supremacy points out how racism is systemic and not only "as a problem of personal prejudices and individual acts of discrimination." White supremacy, therefore, points out a power relationship rooted in exploitation and maintaining the wealth, power and privilege of a few.

Can Non-White People Be Racist?

Omi and Winant (2014) bring up the idea that non-whites can also be racist, and Lipsitz (2006) points out that non-whites can invest in whiteness as well. However, it is important to point out that a lot of scholarship in Ethnic Studies doesn’t always use the words white supremacy. For example, they might talk about white elitism, white as dominant, etc. Even if scholarship does not explicitly name white supremacy as that, everything that helps to perpetuate the maintenance of white dominance is a part of the system of white supremacy. Part of this stems from how the concept of whiteness was created in order to distinguish European colonists from Native Americans and people of color, in particular to distinguish itself as superior. Therefore, talking about whiteness has been a way to explain that the construction of whiteness is constantly created and re-created in order to try to maintain superiority. Further, whiteness operates within a system and also works representationally.

Possessive Investment in Whiteness

Part of the idea here is to recognize proportionality. While there are low-income white people, for example, the majority of white people aren’t poor and those that are typically aren’t poor due to racism. Additionally, while we understand racism as racial discrimination, many scholars in Ethnic Studies specifically emphasize the structural connection within the definition. In the 1990s, Ethnic Studies scholar George Lipsitz coined the term Possessive Investment in Whiteness, or PIW. PIW is a way to explain how white people are encouraged to “buy” into whiteness, promote it, maintain it, uplift it, and exclude access from others. Possessive Investment in Whiteness is to embrace the category of whiteness as a community that embraces white skinned hierarchy in order to obtain advantages that go deeper than everyday privilege. These advantages range from creating laws/policies/procedures that benefit white as a privileged class, that maintains generational wealth by excluding non-whites and profiting from structured discrimination. Part of the maintenance of PIW requires a normalization of whiteness (such as white as the standard of beauty), and adherence to the status quo. Because PIW is embedded in societal structures, it is also self-maintaining and replicating. One example of this is redlining which is explained further in the sidebar below (for more information about related structural racism please see the Racial Wealth Gap).

White Fragility