5.1: The Importance of Audience Analysis

- Page ID

- 106002

The Benefits of Understanding Your Audience

The more you know and understand about the background and needs of your audience, the better you can prepare your speech.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Explain why it is important to understand your audience prior to delivering a speech

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

-

Knowing your audience —their general age, gender, education level, religion, language, culture, and group membership—is the single most important aspect of developing your speech.

- Analyzing your audience will help you discover information that you can use to build common ground between you and the members of your audience.

- A key characteristic in public speaking situations is the unequal distribution of speaking time between the speaker and the audience. This means that the speaker talks more and the audience listens, often without asking questions or responding with any feedback.

Key Terms

- audience: One or more people within hearing range of some message; for example, a group of people listening to a performance or speech; the crowd attending a stage performance.

- audience analysis: A study of the pertinent elements defining the makeup and characteristics of an audience.

- Audience-centered: Tailored to an audience. When preparing a message, the speaker analyzes the audience in order to adapt the content and language usage to the level of the listeners.

Benefits of Understanding Audiences

When you are speaking, you want listeners to understand and respond favorably to what you are saying. An audience is one or more people who come together to listen to the speaker. Audience members may be face to face with the speaker or they may be connected by communication technology such as computers or other media. The audience may be small and private or it may be large and public. A key characteristic of public speaking situations is the unequal distribution of speaking time between speaker and audience. As an example, the speaker usually talks more while the audience listens, often without asking questions or responding with any feedback. In some situations, the audience may ask questions or respond overtly by clapping or making comments.

Audience-Centered Approach to Speaking

Since there is usually limited communication between the speaker and the audience, there is limited opportunity to go back to explain your meaning either during the speech or afterward. When planning a speech, it is important to know about the audience and to adapt the message to the audience. You want to prepare an audience-centered speech, a speech with a focus on the audience.

In public speaking, you are speaking to and for your audience; thus, understanding the audience is a major part of the speech-making process. In audience-centered speaking, getting to know your target audience is one of the most important tasks that you face. You want to learn about the major demographics of the audience, such as general age, gender, education, religion, and culture, as well as to what groups the audience members belong. Additionally, learning about the values, attitudes, and beliefs of the members of your audience will allow you to anticipate and plan your message.

Finding Common Ground by Taking Perspective

You want to analyze your audience prior to your speech so that during the speech you can create a link between you, the speaker, and the audience. You want to be able to figuratively step inside the minds of audience members to understand the world from their perspectives. Through this process, you can find common ground with your audience, which allows you to align your message with what the audience already knows or believes.

Gathering and Interpreting Information

Audience analysis involves gathering and interpreting information about the recipients of oral, written, or visual communication. There are very simple methods for conducting an audience analysis, such as interviewing a small group about its knowledge or attitudes or using more involved methods of analyzing demographic studies of relevant segments of the population. You may also find it useful to look at sociological studies of different age groups or cultural groups. You might also use a questionnaire or rating scale to collect data about the basic demographic information and opinions of your target audience. These examples do not form an all-inclusive list of methods to analyze your audience, but they can help you obtain a general understanding of how you can learn about your audience. After considering all the known factors, a profile of the intended audience can be created, allowing you to speak in a manner that is understood by the intended audience.

Practical Benefits for the Speaker

Understanding who makes up your target audience will allow you to carefully plan your message and adapt what you say to the level of understanding and background of the listeners. Two practical benefits of conducting an audience analysis are (1) to prevent you from saying the wrong thing, such as telling a joke which offends, and (2) to help you speak to your audience in a language they understand about things that interest them. Your speech will be more successful if you can create a message that informs and engages your audience.

What to Look For

Analyze the audience to find the mix of ages, genders, sexual orientations, educational levels, religions, cultures, ethnicities, and races.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Examine your audience based on demographics

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

- A speaker should look at his or her own values, beliefs, attitudes, and biases that may influence his or her perception of others.

- Guard against egocentrism. A speaker must not regard his or her own opinions or interests as being the most important or valid.

- Look at others to understand their background, attitudes, and beliefs.

- Focus on audience demographics such as age, gender, sexual orientation, education, religion, and other relevant population characteristics to analyze the audience.

- The depth of the audience analysis depends of the size of the intended audience and the method of delivery.

Key Terms

- egocentrism: Preoccupation with one’s own internal world; the belief that one’s own opinions or interests are the most important or valid.

- demographics: The characteristics of population such as age, gender, sexual orientation, occupation, education; classification of the characteristics of the people.

Look Inward to Uncover Blinders

A public speaker should turn her mental magnifying glass inward to examine the values, beliefs, attitudes, and biases that may influence her perception of others. The speaker should use this mental picture to look at the audience and view the world from the audience’s perspective. By looking at the audience, the speaker understands their reality.

When the speaker views the audience only through her mental perception, she is likely to engage in egocentrism. Egocentrism is characterized by the preoccupation with one’s own internal world. Egocentrics regard themselves and their own opinions or interests as being the most important or valid. Egocentric people are unable to fully understand or cope with other people’s opinions and a reality that is different from what they are ready to accept.

Understanding Audience Background, Attitudes, and Beliefs

Public speakers must look at who their audience is, their background, attitudes, and beliefs. The speaker should attempt to reach the most accurate and effective analysis of her audience within a reasonable amount of time. For example, speakers can assess the demographics of her audience. Demographics are detailed accounts of human population characteristics and usually rendered as statistical population segments.

For an analysis of audience demographics for a speech, focus on the same characteristics studied in sociology. Audiences and populations comprise groups of people represented by different age groups that:

- Are of the same or mixed genders

- Have experienced the same events

- Have the same or different sexual orientation

- Have different educational attainment

- Participate in different religions

- Represent different cultures, ethnicities, or races

Speakers assess the audience’s attitude – a positive or negative evaluation of people, objects, event, activities, or ideas – toward a specific topic or purpose. The attitudes of the audience may vary from extremely negative to extremely positive, or completely ambivalent. By examining the preexisting beliefs of the audience regarding the speech’s general topic or particular purpose, speakers have the ability to persuade the audience members to buy into the speaker’s argument. This can also help with speech preparation.

Tips for the Speaker

The depth of the audience analysis depends of the size of the intended audience and method of delivery. Speakers use different methods to become familiar with the background, attitudes, and beliefs of audiences in different environments and using various mediums (e.g., videoconferencing, phone, etc). For a small audience, the speaker can simply speak with them in a physical environment. However, the speaker is addressing a larger audience or speaking via teleconferencing or webcasting tools, it may be useful to collect data via surveys or questionnaires.

What to Do with Your Knowledge

Use knowledge about your audience to step into their minds, create an imaginary scenario, and test your ideas.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Identify with your audience by adopting their perspective

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

- A successful speaker is able to step outside her own perceptual framework to understand the world as it is perceived by members of her audience.

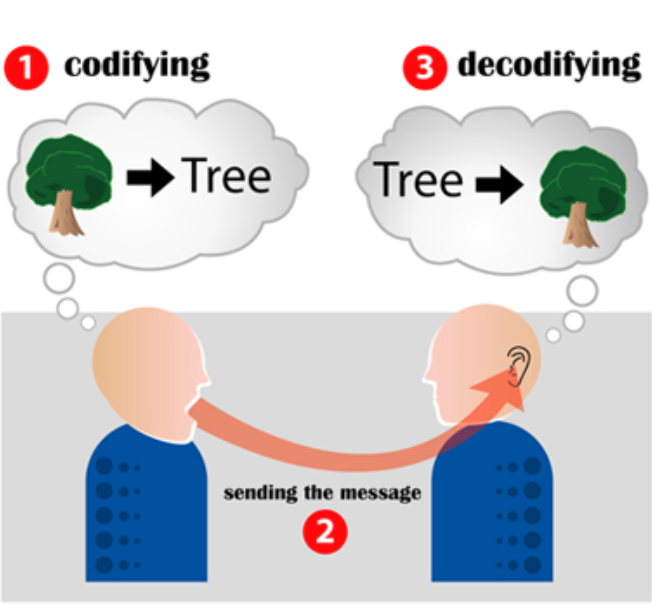

- The speaker engages in a process of first encoding his or her ideas from thoughts into words, then forming a message to be delivered to a group of listeners, or audience. The audience members attempt to decode what the speaker is saying so that they can understand it.

- The better the speaker knows the members of the audience beforehand, the better the speaker can encode a message in a way that the audience can decode successfully.

- One of the most useful strategies for adapting your topic and message to your audience is to use the process of identification to find common ground with them.

- You can use your analysis to create a theoretical, imagined audience of individuals from the diverse backgrounds you have discovered in your audience analysis. Then you can decide whether or not the content will appeal to individuals within that audience.

Key Terms

- encode: to turn one’s ideas into spoken language in order to transmit them to listeners

- message: the verbal and nonverbal components of language, sent to the receiver by the sender, that convey an idea

- Decode: to translate the sender’s spoken idea/message into something the receiver understands by using his or her knowledge of language based on personal experience

Identifying with the listeners

Step in to the minds of your listeners and see if you can identify with them. A successful speaker engages in perspective-taking. While preparing her speech, the speaker steps outside her own perceptual framework to understand the world as it is perceived by members of the audience. When the speaker takes an audience-centered approach to speech preparation, she focuses on the audience and how it will respond to what is being said. In essence, the speaker wants to mentally adopt the perspective of members of the audience in order to see the world as the audience members see it.

Encoding and Decoding

The speaker engages a process of encoding his or her ideas from thoughts into words, and of forming a message which is then delivered to an audience. The audience members then attempt to decode what the speaker is saying so that they can understand it. To better imagine this process, consider the example of encoding and decoding as it applies to the idea of a tree. I know that my audience is in New England and that they are familiar with oak trees. I use the word tree to encode my idea, and because my audience has experienced similar trees, they decode the word tree in the way that I intended. However, I may be thinking about a tree (a palm tree) that is in Hawaii, where I used to live, when I use the word tree to encode my idea. Unfortunately, when my audience decodes my word now, they are still thinking about the oak tree and will not see my palm tree. The audience no longer shares my perspective of the world or my experience with trees.

Finding Common Ground

The more you find out about your audience, the more you can adapt your message to the interests, values, beliefs, and language level of the audience. Once you collect data about your audience, you are ready to summarize your findings and select the language and structure that is best suited to your particular audience. You are on a journey to find common ground in order to identify with your audience. One of the most useful strategies for adapting your topic and message to your audience is to use the process of identification. What do you and your audience have in common? And, conversely, how are you different? What ideas or examples in your speech can your audience identify with?

Creating a Theoretical, Imagined Audience

Create a theoretical, imagined situation to test your view of an audience for practice. You can use your analysis to create what is called a “theoretical, universal audience. ” The universal audience is an imagined audience that serves as a test for the speaker. Imagine in your mind a composite audience that contains individuals from the diverse backgrounds you have discovered in your audience analysis. Next, decide whether or not the content of your speech would appeal to individuals within that audience. What words or examples will the audience understand and what will they not understand? What terms about your subject will you need to define or explain for this audience? How different are the values and opinions you want your audience to accept from the present attitudes and beliefs they may hold?

Tips for the Speaker

In summary, use your knowledge of the audience to adapt your speech accordingly. Adopt the perspective of the audience in order to identify with them, and test out your ideas with an imagined audience composed of people with the background you have discovered through your research.