17.1.2: Sources of Social Change

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 121198

- Boundless

- Boundless

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Sources of Social Change

Social movement theories seek to explain how social movements form and develop.

Learning Objectives

Analyze the similarities and differences in the various social movement theories – deprivation, mass-society, structural-strain, resource-mobilization, political process and culture

Key Points

- Famous social movement theories include deprivation theory, mass- society theory, structural-strain theory, resource -mobilization theory, political process theory and culture theory.

- Deprivation theory posits that social movements emerge among people who believe themselves to be deprived of certain goods or resources.

- Mass-society theory posits that social movements are comprised of people who feel marginalized from the rest of society.

- Structural-strain theory posits that social movements arise as a result of six factors: structural conduciveness, structural strain, growth and spread of a solution, precipating factors, lack of social control, and mobilization.

- Resource-mobilization theory places resources at the center of the emergence and success of social movements. In this case, resources include knowledge, money, media, labor, solidarity, legitimacy, and internal and external support from a powerful elite.

- Cultural theory underscores the importance of culture and addresses the free-rider problem. This theory also emphasizes the critical role of injustice in movement formation, stating that successful movements have to create injustice frames to mobilize people.

Key Terms

- cultural theory: Cultural theory underscores the importance of culture and addresses the free-rider problem. This theory also emphasizes the critical role of injustice in movement formation, stating that successful movements have to create injustice frames to mobilize people.

- injustice frame: An injustice frame is a collection of ideas and symbols that illustrate both how significant the problem the movement is concerned with is as well as what the movement can do to alleviate it.

- free rider: The free-rider problem refers to the idea that people will not be motivated to participate in a social movement that will use up their personal resources like time or money if they can still receive the benefits without participating.

A variety of theories have attempted to explain how social movements develop. Some of the better-known approaches include deprivation theory, mass-society theory, structural-strain theory, resource-mobilization theory, political process theory and culture theory. Deprivation theory and resource-mobilization have been discussed in detail in this chapter’s section entitled “Social Movements. ”

This particular section will thus pay attention to structural-strain theory and culture theory, while mass-society theory and political process theory will be discussed in greater detail later in “International Sources of Social Change” and “External Sources of Social Change,” respectively.

Structural-Strain Theory

Structural-strain theory proposes six factors that encourage social movement development:

- Structural conduciveness: people come to believe their society has problems

- Structural strain: people experience deprivation

- Growth and spread of a solution: a solution to the problems people are experiencing is proposed and disseminates

- Precipitating factors: discontent usually requires a catalyst (often a specific event) to turn it into a social movement

- Lack of social control: the entity to be changed must be at least somewhat open to the change; if the social movement is quickly and powerfully repressed, it may never materialize

- Mobilization: this is the actual organizing and active component of the movement; people do what needs to be done in order to further their cause.

Here is a case in point to illustrate the example of structural-strain theory. Structural conduciveness would occur when a group of people become disgruntled by a change in society. Structural strain is when these people feel a sense of displeasure due to the change, such as being upset or angry. These people propose a solution, such as a demonstration. Precipitating factors, such as being provoked by a non-protester, prompt a negative reaction (such as yelling or throwing something). If the movement is not strong enough, there will be no change; however, if there is enough influence, change is possible. Mobilization occurs when people work together in order to enact social change, such as meeting with government officials in order to change a law or policy.

This theory is subject to circular reasoning since it claims that social/structural strain is the underlying motivation of social movement activism, even though social movement activism is often the only indication that there was strain or deprivation. This kind of circular reasoning is also evident in deprivation theory (people form movements because they lack a certain good or resource), which structural-strain theory partially incorporates and relies upon.

Culture Theory

Culture theory builds upon both the theories of political process (the existence of political opportunities is crucial for movement development) and resource-mobilization (the mobilization of sufficient resources is central to movement formation and success), but it also extends them in two ways. First, it emphasizes the importance of movement culture. Second, it attempts to address the free-rider problem.

Injustice Frames

Both resource-mobilization theory and political process theory incorporate the concept of injustice into their approaches. Culture theory brings this notion of injustice to the forefront of movement creation, arguing that in order for social movements to successfully mobilize individuals, they must develop an injustice frame. An injustice frame is a collection of ideas and symbols that illustrates how significant the problem is and what the movement can do to alleviate it.

Injustice frames have the following characteristics:

- Facts take on their meaning by being embedded in frames, which can render them either relevant and significant or irrelevant and trivial.

- People carry around multiple frames in their heads.

- Successful reframing involves the ability to enter into the worldview of our adversaries.

- All frames contain implicit or explicit appeals to moral principles.

Free-Rider Problem

In emphasizing the injustice frame, culture theory also addresses the free-rider problem. The free-rider problem refers to the idea that people will not be motivated to participate in a social movement that will use up their personal resources (e.g., time, money, etc.) if they can still receive the benefits without participating. In other words, if person X knows that movement Y is working to improve environmental conditions in his neighborhood, he is presented with a choice: to join or not join the movement. If X believes the movement will succeed without her, she can avoid participation in the movement, save her resources, and still reap the benefits—this is free-riding. A significant problem for social movement theory has been to explain why people join movements if they believe the movement can/will succeed without their contribution. Culture theory argues that, in conjunction with social networks being an important contact tool, the injustice frame will provide the motivation for people to contribute to the movement.

Framing processes includes three separate components:

- Diagnostic frame: the movement organization frames the problem—what they are critiquing

- Prognostic frame: the movement organization frames the desirable solution to the problem

- Motivational frame: the movement organization frames a “call to arms” by suggesting and encouraging that people take action

Diagnostic framing of the problem involves an understanding what the problem actually is – what specifically needs to be solved. The prognostic frame is the desired solution – what people think will work to change the situation. Motivational framing is when others are inspired to take action without an actual law or policy in place – such as making a suggestion about how to improve and appealing to people’s morals and values.

External Sources of Social Change

Social change is influenced by random as well as systematic factors, such as government, available resources, and natural environment.

Learning Objectives

Discuss the factors that contribute to social change

Key Points

- Social change is said to come from two sources: random or unique factors (such as climate, weather, or the presence of specific groups of people) and systematic factors (such as government, available resources, and the social organization of society ).

- The political-process theory emphasizes the existence of political opportunities as essential to the formation of social movements.

- According to this theory, the three vital elements of movement formation are insurgent consciousness (collective sense of injustice), organizational strength (in leadership and resources), and political opportunities (the receptivity or vulnerability of the existing political system).

- While this theory has been criticized for not paying enough attention to movement culture, it is also beneficial as it addresses the issue of timing for the emergence of movements.

- Political opportunities refer to the receptivity or susceptibility of the existing political system to challenge and change.

- Since this theory argues that all three components – insurgent consciousness, organizational strength, and political opportunities – are important for movement formation, it is able to address the issue of timing in the emergence of movements (i.e. why do movements form when they do).

- An extension of this theory, known as the political mediation model, considers how the political context facing a movement intersects with the strategic choices that the movement makes.

Key Terms

- pluralism: A social system based on mutual respect for each other’s cultures among various groups that make up a society, wherein subordinate groups do not have to forsake their lifestyle and traditions but, rather, can express their culture and participate in the larger society free of prejudice.

- resource-mobilization theory: Resource-mobilization theory places resources at the center of the emergence and success of social movements. In this case, resources include knowledge, money, media, labor, solidarity, legitimacy, and internal and external support from a powerful elite.

Basically, social change comes from two sources. One source is random or unique factors such as climate, weather, or the presence of specific groups of people. Another source is systematic factors, such as government, available resources, and the social organization of society. On the whole, social change is usually a combination of systematic factors along with some random or unique factors.

There are many theories of social change. Generally, a theory of change should include elements such as structural aspects of change (like population shifts), processes and mechanisms of social change, and directions of change.

Political Process Theory

Political Process Theory, sometimes also known as the Political Opportunity Theory,is an approach to social movements heavily influenced by political sociology. It argues that the success or failure of social movements is primarily affected by political opportunities. Social theorists Peter Eisinger, Sidney Tarrow, David Meyer, and Doug McAdam are considered among the most prominent supporters of this theory. Political Process Theory is similar to resource mobilization theory (which considers the mobilization of resources to be the key ingredient of a successful movement) in many regards, and emphasizes political opportunities as the social structure that is important for social movement development. Political Process Theory argues that there are three vital components for movement formation: insurgent consciousness, organizational strength, and political opportunities.

“Insurgent consciousness” refers back to the notions of deprivation and grievances. In this case, the idea is that certain members of society feel like they are being mistreated or that somehow the system they are a part of is unjust. The insurgent consciousness is the collective sense of injustice that movement members (or potential movement members) feel and serves as the motivation for movement organization.

“Organizational strength” falls in line with resource-mobilization theory, arguing that in order for a social movement to organize it must have strong leadership and sufficient resources.

Finally, “political opportunity” refers to the receptivity or vulnerability of the existing political system to challenge. This vulnerability can be the result of any of the following (or a combination thereof):

- growth of political pluralism

- decline in effectiveness of repression

- elite disunity; the leading factions are internally fragmented

- a broadening of access to institutional participation in political processes

- support of organized opposition by elites

One of the advantages of the political process theory is that it addresses the issue of timing of the emergence of social movements. Some groups may have the insurgent consciousness and resources to mobilize, but because political opportunities are closed, they will not have any success. The theory, argues that all three of these components are important for the successful creation of a movement.

Critics of the political process theory and resource-mobilization theory point out that neither theory discusses the culture of movements to any great degree. This has presented culture theorists an opportunity to expound on the importance of culture.

The Four Social Revolutions

The Four Social Revolutions refer to the identification of social change through modes of subsistence.

Learning Objectives

Analyze the various social revolutions in terms of how each contributes to the development of the next stage, for example, moving from horticulturist to agrarian

Key Points

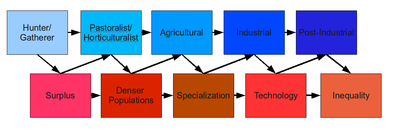

- The development of a society in terms of its primary means of subsistence can be divided into the following stages: hunter-gatherer, pastoral, horticultural, agrarian, industrial, and post-industrial.

- For hunter-gatherer societies, the primary means of subsistence are wild plants and animals. Hunter-gatherers are nomadic and non-hierarchical. Archeological data suggests that all humans were hunter gatherers prior to 13,000 BCE.

- For pastoral societies, the primary means of subsistence are domesticated livestock. Pastoralists are nomadic. They can develop surplus food, which leads to higher population densities than hunter-gatherers, along with social hierarchies and more complicated divisions of labor.

- In horticultural societies, the primary means of subsistence is the cultivation of crops using hand tools.

- In agrarian societies, the primary means of subsistence is the cultivation of crops through a combination of human and non-human means, such as animals and/or machinery.

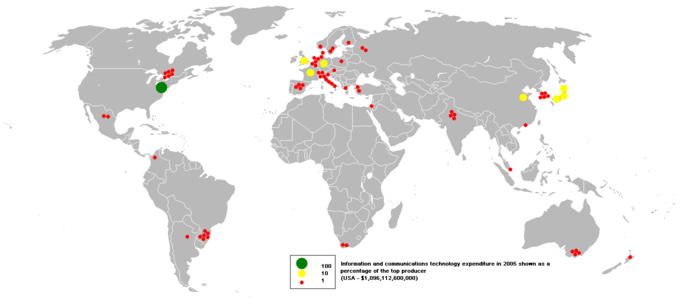

- In industrial societies, the primary means of subsistence is industry, which is a system of production based on the mechanized manufacturing of goods. In post-industrial societies, the primary means of subsistence is service-oriented work, rather than agriculture or industry.

- For horticultural societies, the primary means of subsistence is the cultivation of crops using hand tools.

- For agrarian societies, the primary means of subsistence is the cultivation of crops through a combination of human and non-human means, such as animals and/or machinery.

- In industrial societies, the primary means of subsistence is industry, which is a system of production that is based on the manufacturing of goods.

- In post-industrial societies, the primary means of subsistence is based on service-oriented work, rather than agriculture or industry.

- Changes in the primary means of subsistence can have implications for other aspects of society, leading to developments, such as an increasing degree of specializiation, a greater use of technology and a higher prevalence of inequality.

Key Terms

- agriculture: the art or science of cultivating the ground, including the harvesting of crops, and the rearing and management of livestock; tillage; husbandry; farming

- Hunter-gatherer: a member of a group of people who live by hunting animals and gathering edible plants for their main food sources, and who do not domesticate animals or farm crops

- subsistence: that which furnishes support to animal life; means of support; provisions, or that which produces provisions; livelihood

The Four Social Revolutions

Most societies develop along a similar historical trajectory. Human groups begin as hunter-gatherers, after which they develop pastoralism and/or horticulturalism. After this, an agrarian society typically develops, followed finally by a period of industrialization (sometimes a service industry follows this final stage). Not all societies pass through every stage, and some societies remain at a particular stage for long periods of time, even while others become more complex. Still other societies may jump stages as a result of technological advancements from other societies.

Hunter-Gatherers

The hunter-gatherer way of life is based on the consumption of wild plants and wild animals. Consequently, hunter-gatherers are often mobile, and groups of hunter-gatherers tend to have fluid boundaries and compositions. Typically, in hunter-gatherer societies, men hunt wild animals while women gather fruits, nuts, roots, and other vegetation. Women also hunt smaller wild animals.

The majority of hunter-gatherer societies are nomadic. Because the wild resources of a particular region can be quickly depleted, it is difficult for hunter-gatherers to remain rooted in a place for long. Because of their subsistence system, these societies tend to have very low population densities.

Hunter-gatherer societies are characterized by non-hierarchical social structures, though this is not always the case. Given that hunter-gatherers tend to be nomadic, they generally cannot store surplus food. As a result, full-time leaders, bureaucrats, or artisans are almost never supported by hunter-gatherer societies. The egalitarianism in hunter-gatherer societies tends to extend to gender relations as well.

Pastoralism

In a pastoralist society, the primary means of subsistence are domesticated animals (livestock). Like hunter-gatherers, pastoralists are often nomadic, moving seasonally in search of fresh pastures and water for their animals. In a pastoralist society, there is an increased likelihood of surplus food, which, in turn, often results in greater population densities and the development of both social hierarchies and divisions of labor.

Pastoralist societies still exist. For example, in Australia, the vast, semi-arid interior of the country contains huge pastoral runs called sheep stations. These areas may be thousands of square kilometers in size. The number of livestock allowed in these areas is regulated in order to sustain the land and to ensure that livestock have enough access to food and water.

Horticulturalist Societies

In horticulturalist societies, the primary means of subsistence is the cultivation of crops using hand tools. Like pastoral societies, the cultivation of crops increases population densities and, as a result of food surpluses, allows for an even more complex division of labor. Horticulture differs from agriculture in that agriculture employs animals, machinery, or other non-human means to facilitate the cultivation of crops. Horticulture relies solely on human labor for crop cultivation. Horticultural societies were among the first to establish permanent places of residence. This was due to the fact they no longer had to search for food; rather, they cultivated their own.

Agrarian Societies

In agrarian societies, the primary means of subsistence is the cultivation of crops using a mixture of human and non-human means, like animals and machinery. In agriculture, through the cultivation of plants and the raising of domesticated animals, food, feed, fiber and other desired commodities are produced.

In comparison with the previously mentioned societal types, agriculture supports a much greater population density and allows for the accumulation of excess product. This excess product can either be sold for profit or used during winter months. Because in agricultural societies, farmers are able to feed large numbers of people whose daily activity has nothing to do with food production, a number of important developments occur. These include improved methods of food stores, labor specialization, advanced technology, hierarchical social structures, inequality, and standing armies.

Industrialization

In an industrial society, the primary means of subsistence is industry, which is a system of production based on the mechanized manufacture of goods. Like agrarian societies, industrial societies lead to even greater food surpluses, resulting in even more developed social hierarchies and an even more complex division of labor.

The industrial division of labor, one of the most notable characteristics of this societal type, in many cases leads to a restructuring of social relations. Whereas in pre-industrial societies, relationships would typically develop at one’s place of worship, or through kinship and housing, in industrial societies, relationships and friendships can occur at work.

Post-Industrial

In a post-industrial society, the primary means of subsistence is derived from service-oriented work, as opposed to agriculture or industry. Importantly, the term post-industrial is still debated, in part because it is the current state of society. Generally, in social science, it is difficult to accurately name a phenomenon while it is occurring.

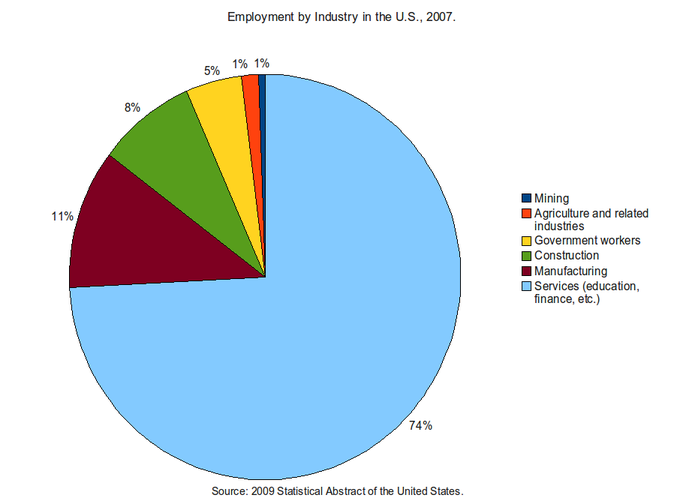

Most highly developed countries are now post-industrial. This means the majority of their workforce works in service-oriented industries, like finance, healthcare, education, or sales, rather than in industry or agriculture. This is the case in the United States.

Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft

Gemeinschaft describes groups in which the community takes precedence over the individual; gesellschaft prioritizes the individual.

Learning Objectives

Examine the similarities and differences between Ferdinand Tonnies’s concepts of gemeinschaft and gesellschaft in relation to human interactions in society

Key Points

- Gemeinschaft and gesellschaft, which can be generally translated as ” community ” and ” society ” respectively, are two sociological categories introduced by German sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies.

- Gemeinschaft describes groups in which the members attach as much, if not more, importance to the groups itself as they do to their own needs. Gemeinschaft can be based on shared space and beliefs, as well as kinship. Gemeinschaft is characterized by ascribed status.

- Gesellschaft refers to groups in which associations never take precedence over the interests of the individual.

- Gesellschaft, unlike gemeinschaft, places more emphasis on secondary relationships rather than familial or community bonds, and it entails achieved, rather than ascribed, status.

- A normal type is a purely conceptual tool that makes use of logic and deduction, as opposed to Max Weber ‘s ideal type, which is a framework used to understand reality that draws on elements from history and society.

Key Terms

- ideal type: An ideal type is not a particular person or thing that exists in the world, but an extreme form of a concept used by sociologists in theories. For example, although there is not a perfectly “modern” society, the term “modern” is used as an ideal type in certain theories to make large-scale points.

- normal type: A normal type is a purely conceptual tool that makes use of logic and deduction, as opposed to Max Weber’s ideal type, which is a framework used to understand reality that draws on elements from history and society.

- community: A group sharing a common understanding and often the same language, manners, tradition and law. See civilization.

Gemeinschaft and gesellschaft are sociological categories for two normal types of human association introduced by the German sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies. A normal type, as coined by Tönnies, is a purely conceptual tool to be built up logically, whereas an ideal type, as coined by Max Weber, is a concept formed by accentuating main elements of a historic/social process. Tönnies’ 1887 book Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft sparked a major revival of corporatist thinking, including an increase in the support for guild socialism, and caused major changes in the field of sociology.

Gemeinschaft

Gemeinschaft (often translated as community) is a group in which individuals take into account the needs and interests of the group as much as, if not more than, their own self interest. Furthermore, individuals in gemeinschaft are regulated by common mores, or beliefs, about the appropriate behavior and responsibilities of members with respect to each other and to the group at large.

Gemeinschaft is thus marked by “unity of will. ” Tönnies saw the family as the most perfect expression of gemeinschaft; however, he expected that gemeinschaft could be based on shared place and shared belief as well as kinship, and he included globally dispersed religious communities as possible examples of gemeinschaft. Gemeinschaft involves ascribed status, which refers to cases in which an individual is assigned a particular status at birth. For example, an individual born to a farmer will come to occupy the parent’s role for the rest of his or her life.

Gemeinschaften are broadly characterized by a moderate division of labour, strong personal relationships, strong families, and relatively simple social institutions. In such communities there is seldom a need to enforce social control externally, due to a collective sense of loyalty individuals feel for society.

Gesellschaft

In contrast, gesellschaft (often translated as society, civil society or association) describes associations in which, for the individual, the larger association never takes precedence over the individual’s self interest, and these associations lack the same level of shared mores. Gesellschaft is maintained through individuals acting in their own self interest. A modern business is a good example of gesellschaft: the workers, managers, and owners may have very little in terms of shared orientations or beliefs—they may not care deeply for the product they are making—but it is in all their self interest to come to work to make money, and thus the business continues. Gesellschaft society involves achieved status where people reach their status through their education and work.

Unlike gemeinschaften, gesellschaften emphasize secondary relationships rather than familial or community ties, and there is generally less individual loyalty to society. Social cohesion in gesellschaften typically derives from a more elaborate division of labor. An example of gemeinschaft in the world today would be an Amish community. The United States would be considered a gesellschaft society. Such societies are considered more susceptible to class conflict as well as racial and ethnic conflicts. The social upheavals during the Reconstruction era of the United States complicated the sociological category of gemeinschaft because former slaves, whose kinship ties were complicated under slavery, forged new communities that shared aspects of both gemeinschaft and gesellschaft.

Talcott Parsons considered gemeinschaft to represent a community of fate, whose members share both good and bad fortune, as opposed to the pursuit of rational self-interest that characterized gesellschaft.

Eric Hobsbawm has argued that as globalisation turns the entire planet into an increasingly remote kind of gesellschaft, similarly collective identity politics seek a factitious remaking of the qualities of gemeinschaft by reforging artificial group bonds and identities.

Fredric Jameson highlights the ambivalent envy felt by members of gesellschaft for remaining enclaves of gemeinschaft, even as the former inevitably corrode the existence of the latter.

Capitalism, Modernization, and Industrialization

Sociologists Weber, Marx and Durkheim envisioned different impacts the Industrial Revolution would have on both the individual and society.

Learning Objectives

Compare the similarities and differences between Weber’s Rationalization, Marx’s Alienation and Durkheim’s Solidarity In relation to the Industrial Revolution

Key Points

- Weber imagined that an increasing rationalization of society would lead to man being trapped in a iron cage of rationality and bureaucracy.

- Marx believed that capitalism resulted in the alienation of workers from their own labor and from one another, preventing them from achieving self-realization ( species being ).

- Finally, Durkheim believed that industrialization would lead to decreasing social solidarity.

- Bureaucracy is a type of organizational or institutional management that is based upon legal-rational authority. Weber believed that industrialization was leading to a growing influence of rational ideas and thought in culture, which, in turn, led to the bureaucratization of society.

- Karl Marx understood species being to be the original or intrinsic essence of the species. A simplified understanding of species being is that it is a form of self-realization or self-actualization resulting from fulfilling or meaningful work.

- Durkheim imagined that industrialization would lead to a decrease in social solidarity, which can be defined as a sense of community. He referred to this decrease in social solidarity as anomie, a French word for chaos.

- Durkheim imagined that industrialization would lead to a decrease in social solidarity, which can be defined as a sense of community.

- Durkheim referred to the decrease in social solidarity resulting from industrialization as anomie, a French word for chaos.

- Industrializing societies would be characterized by specialization in that individuals would occupy different roles and occupations in a given society. According to Durkheim, specialization would lead to interdependence between the various components of society. He referred to this interdependence as organic solidarity.

- Societies exhibit mechanical solidarity when the source of its cohesion is the homogeneity of its individuals in terms of their work, educational and religious training and lifestyles.

Key Terms

- species being: Karl Marx understood species being to be the original or intrinsic essence of the species, which is characterized by pluralism and dynamism: all beings possess the tendency and desire to engage in multiple activities to promote their mutual survival, comfort and sense of inter-action. A simplified understanding of species being is that it is a form of self-realization or self-actualization resulting from fulfilling or meaningful work.

- anomie: Alienation or social instability caused by erosion of standards and values.

- alienation: Emotional isolation or dissociation.

As Western societies transitioned from pre-industrial economies based primarily on agriculture to industrialized societies in the 19th century, some people worried about the impacts such changes would have on society and individuals. Three early sociologists, Max Weber, Karl Marx, and Emile Durkheim, envisioned different outcomes of the Industrial Revolution on both the individual and society and described these effects in their work.

Weber and Rationalization

Max Weber was particularly concerned about the rationalization of society due to the Industrial Revolution and how this change would affect humanity’s agency and happiness. Weber’s understanding of rationalization was three-fold: firstly, as individual cost-benefit calculations; secondly, as the transformation of society into a bureaucratic entity; lastly, and on a much wider scale, as the opposite of perceiving reality through the lens of mystery and magic (disenchantment). Since Weber viewed rationalization as the driving force of society and given that bureaucracy was the most rational form of institutional governance, Weber believed bureaucracy would spread until it ruled society.

As Weber did not see any alternative to bureaucracy, he believed it would ultimately lead to an iron cage: there would be no way to escape it. Weber viewed this as a bleak outcome that would affect individuals’ happiness as they would be forced to function in a society with rigid rules and norms without the possibility of change.

Related to rationalization is the process of disenchantment, in which the world is becoming more explained and less mystical, moving from polytheistic religions to monotheistic ones and finally to the Godless science of modernity. Those processes affect all of society, removing “sublime values… from public life” and making art less creative.

Marx and Alienation

Karl Marx took a different perspective on the Industrial Revolution. According to Marx, a capitalist system results in the alienation (or estrangement) of people from their “species being.” Species being is a concept that Marx deploys to refer to what he sees as the original or intrinsic essence of the species, which is characterized both by plurality and dynamism: all beings possess the tendency and desire to engage in multiple activities to promote their mutual survival, comfort and sense of inter-connection

In a capitalist society (which co-evolved with the Industrial Revolution), the proletariat, or working class, own only their labor power and not the fruits of their labor (i.e. the results of production). The capitalists, or bourgeoisie, employ the proletariat for a living wage, and, in turn, they keep the products of the labor. A major implication of this system is that workers lose the ability to determine their lives and destinies by being deprived of the right to conceive of themselves as the director of their actions, to determine the character of their actions, to define their relationship to other actors, and to use or own the value of what is produced by their actions. This is what Marx refers to as alienation.

Durkheim and Solidarity

Similar to Weber and Marx, Durkheim also believed that the societal changes brought upon by industrialzation could eventually lead to unhappiness. According to Durkheim, an important component of social life was social solidarity, which can be understood as a sense of community. For example, in his classic study, Suicide, Durkheim argued that one of the root causes of suicide was a decrease in social solidarity, a phenomenon which Durkheim referred to as anomie (French for chaos). Durkheim also argued that the increasing emphasis on individualism in Protestant religions – in contrast to Catholicism – contributed to a corresponding rise in anomie, which resulted in higher suicide rates among Protestants than among Catholics.

According to Durkheim, the types of social solidarity correlate with types of society. Durkheim introduced the terms “mechanical” and “organic solidarity” as part of his theory of the development of societies in The Division of Labour in Society (1893). In a society exhibiting mechanical solidarity, its cohesion and integration comes from the homogeneity of individuals—people feel connected through similar work, educational and religious training, and lifestyle. Mechanical solidarity normally operates in “traditional” and small scale societies. Organic solidarity comes from the interdependence that arises from specialization of work and the complementarities between people—a development which occurs in “modern” and “industrial” societies. Thus, organic solidarity is social cohesion based upon the dependence individuals have on each other in more advanced societies. Although individuals perform different tasks and often have different values and interest, the order and very solidarity of society depends on their reliance on each other to perform their specified tasks.

Cultural Evolution

Over time, the concept of culture has transformed into a more inclusive concept.

Learning Objectives

Outline ways the concept of culture has changed over time, from evaluative to inclusive

Key Points

- Although biological evolution may have originally resulted in culture, research suggests that culture is not only a supplement to evolution, but can also influence it.

- Ultimately, the category of “culture” is, like all classifications, an artificial distinction.

- The fact that all human beings have cultures must, at some level, be a consequence of human evolution. However, evolution cannot be used as a way of distinguishing between different cultures, as this is a form of, or can legitimize forms of, racism.

- Since culture is dynamic and can be taught and learned, it can facilitate the adaptation of humans to different physical environments and changes in environmental conditions. In this way, culture acts as a supplement to evolution.

- Cultural relativism posits that cultures are to be considered as bounded wholes and have to be understood in their own terms. Cultures are not better or worse than each other, just different.

- Recent research suggests that culture can influence human evolution.

- When studying culture, it is important to bear in mind that the notion of culture can have multiple levels of meaning, or, in other words, levels of abstraction.

Key Terms

- symbol: Any object, typically material, which is meant to represent another (usually abstract), even if there is no meaningful relationship.

- cultural relativism: Cultural relativism is a principle that was established as axiomatic in anthropological research by Franz Boas in the first few decades of the twentieth century, and later popularized by his students. Boas first articulated the idea in 1887: “…civilization is not something absolute, but… is relative, and… our ideas and conceptions are true only so far as our civilization goes. “

- evolution: gradual directional change, especially one leading to a more advanced or complex form; growth; development

During the Romantic Era, scholars in Germany, especially those concerned with nationalism, developed a more inclusive notion of culture as a worldview. That is, each ethnic group is characterized by a distinct and incommensurable worldview. Although more inclusive, this approach to culture still allowes for distinctions between civilized and primitive, or tribal, cultures.

By the late 19th century, anthropologists changed the concept of culture to include a wider variety of societies. This resulted in the concept of culture as objects and symbols; the meaning given to those objects and symbols; and the norms, values, and beliefs that pervade social life.

This new perspective removed the evaluative element of the concept of culture, and instead proposed distinctions rather than rankings between different cultures. For instance, the high culture of elites is now contrasted with popular or pop culture. In this sense, high culture no longer refers to the idea of being cultured, as all people are cultured. High culture simply refers to the objects, symbols, norms, values, and beliefs of a particular group of people; popular culture refers to the same.

Most social scientists today reject the cultured vs. uncultured concept of culture. Instead, social scientists accept and advocate the definition of culture outlined above as being the “nurture” component of human social life. Social scientists recognize that non-elites are as cultured as elites, and that non-Westerners are just as civilized; they simply have a different culture.

The understanding of culture as a symbolic system with adaptive functions that vary from place to place led anthropologists to define different cultures by distinct patterns or structures of enduring, conventional sets of meaning. These took concrete form in a variety of artifacts, both symbolic, such as myths and rituals, and material, including tools, the design of housing, and the planning of villages. Anthropologists distinguish between material culture and symbolic culture, not only because each reflects different kinds of human activity, but also because each constitutes different kinds of data that require different methodologies to study.

Cultural Relativism

This view of culture, which came to dominate anthropology between World War I and World War II, implies that each culture is bounded and has to be understood as a whole, on its own terms. The result is a belief in cultural relativism, which suggests that there are no “better” or “worse” cultures, just different cultures.

Culture as a Product of Biology

Biology and nature are deeply connected and share a complex relationship. Early studies of this relationship revealed that culture is actually a product of biology. More recent research, however, suggests that human culture has reversed this particular causal direction and, culture can actually influence human evolution. One well-known example of this is the rapid spread of a gene that produces a protein that allows humans to digest lactose. This adaptation spread quickly in Europe around 4,000 BCE with the domestication of mammals and the consumption of animal milk by humans. Prior to this adaptation, this gene was switched off after children were weaned. Thus, the change in culture (drinking milk from other mammals) eventually led to changes in human genetics. Genetics, therefore, resulted in culture, which is now affecting genetics.

Another important element in the understanding of culture is level of abstraction. Culture ranges from the concrete, cultural object (e.g., the understanding of a work of art) to micro-level interpersonal interactions (e.g., the socialization of a child by his/her parents) to a macro-level influence on entire societies (e.g., the Puritanical roots of the U.S. that can be used to justify the exportation of democracy, as was the case with the Iraq War). When trying to understand the concept of culture, it is important to remember that the concept can have multiple levels of meaning.

Natural Cycles

Social cycle theories argue that historical events and the different stages of society generally go through recurring cycles.

Learning Objectives

Examine the change in social cycle theories throughout history, ranging from ideas of “life cycles” to political-demographic cycles

Key Points

- Precursors to social cycle theories can be found in the works of Polybius, Ibn Khaldun, and Giambattista Vico, who all argued that history can be defined as repeating cycles of events..

- Classical social cycle theories include the idea that civilizations have “life cycles,” as was proposed by Nikolai Danilewski and Oswald Spengler.

- The first true social cycle theory was introduced by Vilfredo Pareto, who divided the elite social class into cunning foxes and violent lions and claimed that power constantly passes from one group to the other.

- Classical social cycle theorist, Petrim A. Sorokin, viewed societies as moving between three cultural mentalities: ideational, sensate and idealistic.

- An important development in modern social cycle theories is the discovery that political-demographic cycles are a basic feature of the long-term dynamic social processes of complex agrarian systems. Theories of long-term political-demographic cycles take into account social progress.

- Thomas Malthus proposed that limited resources will act as a check on population growth among humans. A Malthusian catastrophe (also known by other names) refers to the forced return to subsistence-level conditions when population growth has outstripped agricultural production.

- An important development in modern social cycle theories is the discovery that political-demographic cycles are a basic feature of the long-term dynamic social processes of complex agrarian systems. Theories of long-term political-demographic cycles take into account social progress.

- Thomas Malthus proposed that limited resources will act as a check on population growth among humans. A Malthusian catastrophe (also known by other names) refers to the forced return to subsistence-level conditions when population growth has outstripped agricultural production.

- P.R. Sarkar also accounts for social progress in his Law of Social Cycle by considering human spiritual development. Social stasis and the subsequent collapse of regimes occurs when the ruling class treats other members of society poorly in order to advance its own selfish interests.

Key Terms

- Malthusian catastrophe: A Malthusian catastrophe (also known as Malthusian check) was originally foreseen to be a forced return to subsistence-level conditions once population growth had outpaced agricultural production.

- political-demographic cycles: One of the most important recent findings in the study of the long-term dynamic social processes was the discovery of the political-demographic cycles as a basic feature of the dynamics of complex agrarian systems.

- Polybius: Polybius was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic Period noted for his work, The Histories, which covered the period of 220–146 BC in detail. The work describes in part the rise of the Roman Republic and its gradual domination over Greece.

Social cycle theories are among the earliest social theories in sociology. Unlike the theory of social evolutionism, which views the evolution of society and human history as progressing in some new, unique direction(s), sociological cycle theory argues that events and stages of society and history generally repeat themselves in cycles. Such a theory does not necessarily imply that there cannot be any social progress. In fact, the early theory of Sima Qian, a Chinese historiographer of the Han Dynasty and typically considered to be the father of Chinese historiography, the more recent theories of long-term (“secular”) political-demographic cycles as well as the Varnic theory of P.R. Sarkar all make an explicit accounting of social progress.

Predecessors

The interpretation of history as repeating cycles of Dark and Golden Ages was a common belief among ancient cultures. The more limited cyclical view of history defined as repeating cycles of events was put forward in the academic world in the 19th century in historiography (the study of the history and methodology of the discipline of history) and is a concept that falls under the category of sociology. However, the precursors to this analysis include Polybius, a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period, Ibn Khaldun, a Muslim historiographer and historian, who saw the rise and fall of Asabiyyah (the sense of community among humans) as the reason behind the emergence and decline of civilizations, and, finally, Giambattista Vico, an Italian philosopher, who argued that civilizations occur in recurring cycles consisting of three ages: the divine, the heroic and the human. The Saeculum, which refers to the period of time during which the renewal of a human population would occur, was identified in Roman times. More recently, P. R. Sarkar in his Social Cycle Theory has used this idea to elaborate his interpretation of history.

Classical Theories

Among the prominent historiosophers, Russian philosopher Nikolai Danilewski (1822–1885) is notable. In Rossiia i Europa (1869), he differentiated between various smaller civilizations (Egyptian, Chinese, Persian, Greek, Roman, German, and Slav, among others) and asserted that each civilization has a life cycle. To illustrate this claim, he pointed out that by the end of the 19th century the Roman-German civilization was in decline, while the Slav civilization was approaching its Golden Age. A similar theory was put forward by Oswald Spengler (1880–1936) who in his Der Untergang des Abendlandes (1918) predicted that the Western civilization was about to collapse.

The first social cycle theory in sociology was created by Italian sociologist and economist Vilfredo Pareto (1848–1923) in his Trattato di Sociologia Generale (1916). He centered his theory on the concept of an elite social class, which he divided into cunning “foxes” and violent “lions. ” In his view of society, the power constantly passes from the “foxes” to the “lions” and vice versa.

Sociological cycle theory was also developed by Pitirim A. Sorokin (1889–1968) in his Social and Cultural Dynamics (1937, 1943). He classified societies according to their “cultural mentality. ” which can be ideational (reality is spiritual), sensate (reality is material), or idealistic (a synthesis of the two). He interpreted the contemporary West as a sensate civilization dedicated to technological progress and prophesied its fall into decadence and the emergence of a new ideational or idealistic era.

Modern Theories

One of the most important recent findings in the study of the long-term dynamic social processes was the discovery of the political-demographic cycles as a basic feature of the dynamics of complex agrarian systems. The presence of political-demographic cycles in the pre-modern history of Europe and China, and in chiefdom level societies worldwide has been known for quite a long time, and already in the 1980s more or less developed mathematical models of demographic cycles started to be produced.

Recently the most important contributions to the development of the mathematical models of long-term (“secular”) sociodemographic cycles have been made by Sergey Nefedov, Peter Turchin, Andrey Korotayev, and Sergey Malkov. What is important is that on the basis of their models Nefedov, Turchin and Malkov have managed to demonstrate that sociodemographic cycles were a basic feature of complex agrarian systems (and not a specifically Chinese or European phenomenon).

It has become possible to model these dynamics mathematically in a rather effective way. Modern social scientists from different fields have introduced cycle theories to predict civilizational collapses in approaches that apply contemporary methods, which update the approach of Spengler, such as the work of Joseph Tainter suggesting a civilizational life-cycle.

Ogburn’s Theory

William F. Ogburn’s theory suggests that technology is the primary engine of progress.

Learning Objectives

Summarize the main points of Ogburn’s theory of social change, in terms of its four main stages

Key Points

- Ogburn’s four stages of technical development are invention, accumulation, diffusion and adjustment.

- Although his theory is associated with technological determinism, the two are far from perfectly aligned.

- Technological determinism is a theory that argues technology is responsible for determining a society ‘s structure and values.

- Cultural lag is the period during which non-material culture strives to adjust to new technology and inventions.

- Cultural lag is the period during which non-material culture strives to adjust to new technology and inventions.

- Ogburn’s four stages of technical development are invention, accumulation, diffusion and adjustment.

- Invention is the process by which new kinds of technology are produced.

- Accumulation is the growth of technology as a result of new inventions outpacing the decline of old technology.

- Diffusion is the spread of new ideas from one culture to another, or from one field of activity to another, which leads to the convergence of different technologies that then combine to form new inventions.

- Adjustment is the process by which non-material aspects of society adjust to new technology.

Key Terms

- cultural lag: The term cultural lag refers to the notion that culture takes time to catch up with technological innovations, and that social problems and conflicts are caused by this lag.

- soft determinism: Soft determinism posits that, although technology drives progress, people still may have the chance to make decisions regarding social outcomes.

- hard determinism: Hard determinism is the idea that technology governs social structures and activities.

William Fielding Ogburn (June 29, 1886 – April 27, 1959) was an American sociologist, statistician, and educator. Perhaps Ogburn’s most enduring intellectual legacy is the theory of social change he offered in 1922. He suggested that technology is the primary engine of progress, but it is also tempered by social responses to it. Thus, his theory is often associated with technological determinism, a reductionist theory that presumes a society’s technology drives the development of its social structure and cultural values.

Hard Determinism versus Soft Determinism

Hard determinists view technology as developing independent from social concerns. They believe that technology creates a set of powerful forces acting to regulate our social activity and its meaning.

Soft determinism, as the name suggests, is a more passive view of the way technology interacts with socio-political situations. Soft determinists still subscribe to the fact that technology is the guiding force in our evolution, but maintain that we have a chance to make decisions regarding the outcomes of a situation. Ogburn, in fact, proposed a slightly different variant of soft determinism, in which society must adjust to the consequences of major inventions, but often does so only after a period of cultural lag. Cultural lag, a term coined by Ogburn, refers to a period of maladjustment, which occurs when the non-material culture is struggling to adapt to new material conditions.

Stages of Technological Development

Ogburn posited four stages of technical development: invention, accumulation, diffusion, and adjustment.

Invention is the process by which new forms of technology are created. Inventions are collective contributions to an existing cultural base that cannot occur unless the society has already gained a certain level of knowledge and expertise in the particular area.

Accumulation is the growth of technology due to the fact that the invention of new things outpaces the process by which old inventions become obsolete or are forgotten—some inventions (such as writing) promote this accumulation process.

Diffusion is the spread of an idea from one cultural group to another, or from one field of activity to another. As diffusion brings inventions together, they combine to form new inventions.

Adjustment is the process by which the non-technical aspects of a culture respond to invention. Any retardation of this adjustment process causes cultural lag.

Contributors and Attributions

CC licensed content, Specific attribution