1.1: Communication - History and Forms

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 23965

- Anonymous

- LibreTexts

Learning Objectives

- Define communication.

- Discuss the history of communication from ancient to modern times.

- List the five forms of communication.

- Distinguish among the five forms of communication.

- Review the various career options for students who study communication.

Before we dive into the history of communication, it is important that we have a shared understanding of what we mean by the word communication. For our purposes in this book, we will define communication as the process of generating meaning by sending and receiving verbal and nonverbal symbols and signs that are influenced by multiple contexts.

From Aristotle to Obama: A Brief History of Communication

Our focus in this book is on human communication. Even though all animals communicate, as human beings we have a special capacity to use symbols to communicate about things outside our immediate temporal and spatial reality (Dance & Larson). The ability to think outside our immediate reality is what allows us to create elaborate belief systems, art, philosophy, and academic theories.

This eventually led to the development of a “Talking Culture” during the “Talking Era.” During this 150,000 year period of human existence, ranging from 180,000 BCE to 3500 BCE, talking was the only medium of communication, aside from gestures, that humans had (Poe, 2011).

The beginning of the “Manuscript Era” marked the turn from oral to written culture. The emergence of elite classes and the rise of armies required records and bookkeeping, which furthered the spread of written symbols. During the near 5,000-year period of the “Manuscript Era,” literacy, or the ability to read and write, didn’t spread far beyond the most privileged in society. In fact, it wasn’t until the 1800s that widespread literacy existed in the world.

The end of the “Manuscript Era” marked a shift toward a rapid increase in communication technologies. The “Print Era” was marked by the invention of the printing press and the ability to mass-produce written texts. This period gave way to the “Audiovisual Era,” which only lasted 140 years, was marked by the invention of radio, telegraph, telephone, and television. Our current period, the “Internet Era,” has only lasted from 1990 until the present. This period has featured the most rapid dispersion of a new method of communication, as the spread of the Internet and the expansion of digital and personal media signaled the beginning of the digital age.

Aristotle is a logical person to start with when tracing the development of the communication scholarship. His writings on communication, although not the oldest, are the most complete and systematic. Ancient Greek philosophers and scholars such as Aristotle theorized about the art of rhetoric, which refers to speaking well and persuasively. Today, we hear the word rhetoric used in negative ways. This leads us to believe that rhetoric refers to misleading, false, or unethical communication, which is not at all in keeping with the usage of the word by ancient or contemporary communication experts. Much of the writing and teaching about rhetoric conveys the importance of being an ethical rhetor, or communicator.

The connections among rhetoric, policy making, and legal proceedings show that communication and citizenship have been connected since the study of communication began. Throughout this book, we will continue to make connections between communication, ethics, and civic engagement.

Communication studies as a distinct academic discipline with departments at universities and colleges has only existed for a little over one hundred years (Keith, 2008). In 1914, a group of ten speech teachers started the National Association of Academic Teachers of Public Speaking, which eventually evolved into today’s National Communication Association. There was a distinction of focus and interest among professors of speech. While some focused on the quality of ideas, arguments, and organization, others focused on coaching the performance and delivery aspects of public speaking (Keith, 2008). Instruction in the latter stressed the importance of “oratory” or “elocution,” and this interest in reading and speaking aloud is sustained today in theatre and performance studies and also in oral interpretation classes, which are still taught in many communication departments.

The formalization of speech departments led to an expanded view of the role of communication. Even though Aristotle and other ancient rhetoricians and philosophers had theorized the connection between rhetoric and citizenship, the role of the communicator became the focus instead of solely focusing on the message. James A. Winans, one of the first modern speech teachers and an advocate for teaching communication in higher education, said there were “two motives for learning to speak. Increasing one’s chance to succeed and increasing one’s power to serve” (Keith, 2008). Later, as social psychology began to expand in academic institutions, speech communication scholars saw places for connection to further expand definitions of communication to include social and psychological contexts.

Today, you can find elements of all these various aspects of communication being studied in communication departments. If we use President Obama as a case study, we can see the breadth of the communication field. Within one department, you may have fairly traditional rhetoricians who study the speeches of President Obama in comparison with other presidential rhetoric. Others may study debates between presidential candidates, dissecting the rhetorical strategies used, for example, by Mitt Romney and Barack Obama. Expanding from messages to channels of communication, scholars may study how different media outlets cover presidential politics. At an interpersonal level, scholars may study what sorts of conflicts emerge within families that have liberal and conservative individuals. At a cultural level, communication scholars could study how the election of an African American president creates a narrative of postracial politics. Our tour from Aristotle to Obama was quick, but hopefully instructive. Now let’s turn to a discussion of the five major forms of communication

Forms of Communication

The five main forms of communication are intrapersonal, interpersonal, group, public, and mass communication. In the following we will discuss the similarities and differences among each form of communication, including its definition, level of intentionality, goals, and contexts.

Intrapersonal Communication

Intrapersonal communication is communication with oneself using internal vocalization or reflective thinking. Intrapersonal communication is triggered by some internal or external stimulus. We may, for example, communicate with our self about what we want to eat due to the internal stimulus of hunger, or we may react intrapersonally to an event we witness. Unlike other forms of communication, intrapersonal communication takes place only inside our heads. The other forms of communication must be perceived by someone else to count as communication.

Intrapersonal communication serves several social functions. Internal vocalization, or talking to ourselves, can help us achieve or maintain social adjustment (Dance & Larson, 1972). For example, a person may use self-talk to calm himself down in a stressful situation, or a shy person may remind herself to smile during a social event. Intrapersonal communication also helps build and maintain our self-concept.

We also use intrapersonal communication or “self-talk” to let off steam, process emotions, think through something, or rehearse what we plan to say or do in the future. Competent intrapersonal communication helps facilitate social interaction and can enhance our well-being. Conversely, the breakdown in the ability of a person to intrapersonally communicate is associated with mental illness (Dance & Larson, 1972).

Sometimes we intrapersonally communicate for the fun of it. We also communicate intrapersonally to pass time. In both of these cases, intrapersonal communication is usually unplanned and doesn’t include a clearly defined goal (Dance & Larson, 1972). We can, however, engage in more intentional intrapersonal communication. In fact, deliberate self-reflection can help us become more competent communicators as we become more mindful of our own behaviors. For example, your internal voice may praise or scold you based on a thought or action.

Intrapersonal communication is not created with the intention that another person will perceive it. In all the other levels, the fact that the communicator anticipates consumption of their message is very important.

Interpersonal Communication

Interpersonal communication is communication between people whose lives mutually influence one another. Interpersonal communication builds, maintains, and ends our relationships, and we spend more time engaged in interpersonal communication than the other forms of communication. Interpersonal communication occurs in various contexts and is addressed in subfields of study within communication studies such as intercultural communication, organizational communication, health communication, and computer-mediated communication. After all, interpersonal relationships exist in all those contexts.

Interpersonal communication can be planned or unplanned, but since it is interactive, it is usually more structured and influenced by social expectations than intrapersonal communication. Interpersonal communication is also more goal oriented than intrapersonal communication and fulfills instrumental and relational needs. In terms of instrumental needs, the goal may be as minor as greeting someone to fulfill a morning ritual or as major as conveying your desire to be in a committed relationship with someone. Interpersonal communication meets relational needs by communicating the uniqueness of a specific relationship. Instances of miscommunication and communication conflict most frequently occur here (Dance & Larson, 1972). In order to be a competent interpersonal communicator, you need conflict management skills and listening skills, among others, to maintain positive relationships.

Group Communication

Group communication is communication among three or more people interacting to achieve a shared goal. Group work in an academic setting provides useful experience and preparation for group work in professional settings. Organizations have been moving toward more team-based work models, and whether we like it or not, groups are an integral part of people’s lives.

Group communication is more intentional and formal than interpersonal communication. Individuals in a group are often assigned to their position within a group. Group communication is often task focused, meaning that members of the group work together for an explicit purpose or goal that affects each member of the group. Since group members also communicate with and relate to each other interpersonally and may have preexisting relationships or develop them during the course of group interaction, elements of interpersonal communication occur within group communication too.

Public Communication

Public communication is a sender-focused form of communication in which one person is typically responsible for conveying information to an audience. Public speaking is something that many people fear, or at least don’t enjoy. But, just like group communication, public speaking is an important part of our academic, professional, and civic lives. When compared to interpersonal and group communication, public communication is the most consistently intentional, formal, and goal-oriented form of communication we have discussed so far.

Public communication, at least in Western societies, is also more sender focused than interpersonal or group communication. Despite being formal, public speaking is very similar to the conversations that we have in our daily interactions. Although public speakers don’t necessarily develop individual relationships with audience members, they still have the benefit of being face-to-face with them so they can receive verbal and nonverbal feedback.

Mass Communication

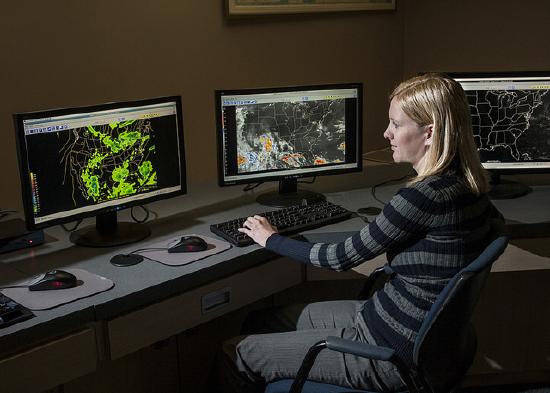

Public communication becomes mass communication when it is transmitted to many people through print or electronic media. Radio, podcasts, and books are other examples of mass media. The technology required to send mass communication messages distinguishes it from the other forms of communication. A certain amount of intentionality goes into transmitting a mass communication message since it usually requires one or more extra steps to convey the message. The intentionality and goals of the person actually creating the message, such as the writer, television host, or talk show guest, vary greatly.

Unlike interpersonal, group, and public communication, there is no immediate verbal and nonverbal feedback loop in mass communication. With new media technologies like Twitter, blogs, and Facebook, feedback is becoming more immediate.

The technology to mass-produce and distribute communication messages brings with it the power for one voice or a series of voices to reach and affect many people. The potential consequences of unethical mass communication are important to consider.

“Getting Real”

What Can You Do with a Degree in Communication Studies?

You’re hopefully already beginning to see that communication studies is a diverse and vibrant field of study. The multiple subfields and concentrations within the field allow for exciting opportunities for study in academic contexts but can create confusion and uncertainty when a person considers what they might do for their career after studying communication. It’s important to remember that not every college or university will have courses or concentrations in all the areas discussed next. Look at the communication courses offered at your school to get an idea of where the communication department on your campus fits into the overall field of study. Some departments are more general, offering students a range of courses to provide a well-rounded understanding of communication. Many departments offer concentrations or specializations within the major such as public relations, rhetoric, interpersonal communication, electronic media production, corporate communication. If you are at a community college and plan on transferring to another school, your choice of school may be determined by the course offerings in the department and expertise of the school’s communication faculty. It would be unfortunate for a student interested in public relations to end up in a department that focuses more on rhetoric or broadcasting, so doing your research ahead of time is key.

Since communication studies is a broad field, many students strategically choose a concentration and/or a minor that will give them an advantage in the job market. Specialization can definitely be an advantage, but don’t forget about the general skills you gain as a communication major. This book, for example, should help you build communication competence and skills in interpersonal communication, intercultural communication, group communication, and public speaking, among others. You can also use your school’s career services office to help you learn how to “sell” yourself as a communication major and how to translate what you’ve learned in your classes into useful information to include on your resume or in a job interview.

The main career areas that communication majors go into are business, public relations / advertising, media, nonprofit, government/law, and education.[1] Within each of these areas there are multiple career paths, potential employers, and useful strategies for success. For more detailed information, visit http://whatcanidowiththismajor.com/major/communication-studies.

- Business. Sales, customer service, management, real estate, human resources, training and development.

- Public relations / advertising. Public relations, advertising/marketing, public opinion research, development, event coordination.

- Media. Editing, copywriting, publishing, producing, directing, media sales, broadcasting.

- Nonprofit. Administration, grant writing, fund-raising, public relations, volunteer coordination.

- Government/law. City or town management, community affairs, lobbying, conflict negotiation / mediation.

- Education. High school speech teacher, forensics/debate coach, administration and student support services, graduate school to further communication study.

- Which of the areas listed above are you most interested in studying in school or pursuing as a career? Why?

- What aspect(s) of communication studies does/do the department at your school specialize in? What concentrations/courses are offered?

- Whether or not you are or plan to become a communication major, how do you think you could use what you have learned and will learn in this class to “sell” yourself on the job market?

Key Takeaways

- Getting integrated: Communication is a broad field that draws from many academic disciplines. This interdisciplinary perspective provides useful training and experience for students that can translate into many career fields.

- Communication is the process of generating meaning by sending and receiving symbolic cues that are influenced by multiple contexts.

- Ancient Greeks like Aristotle and Plato started a rich tradition of the study of rhetoric in the Western world more than two thousand years ago. Communication did not become a distinct field of study with academic departments until the 1900s, but it is now a thriving discipline with many subfields of study.

- There are five forms of communication: intrapersonal, interpersonal, group, public, and mass communication.

- Intrapersonal communication is communication with oneself and occurs only inside our heads.

- Interpersonal communication is communication between people whose lives mutually influence one another and typically occurs in dyads, which means in pairs.

- Group communication occurs when three or more people communicate to achieve a shared goal.

- Public communication is sender focused and typically occurs when one person conveys information to an audience.

- Mass communication occurs when messages are sent to large audiences using print or electronic media.

Exercise

- Over the course of a day, keep track of the forms of communication that you use. Make a pie chart of how much time you think you spend, on an average day, engaging in each form of communication (intrapersonal, interpersonal, group, public, and mass).

References

Dance, F. E. X. and Carl E. Larson, The Functions of Human Communication: A Theoretical Approach (New York, NY: Holt, Reinhart, and Winston, 1976), 23.

Keith, W., “On the Origins of Speech as a Discipline: James A. Winans and Public Speaking as Practical Democracy,” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 38, no. 3 (2008): 239–58.

McCroskey, J. C., “Communication Competence: The Elusive Construct,” in Competence in Communication: A Multidisciplinary Approach, ed. Robert N. Bostrom (Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 1984), 260.

Poe, M. T., A History of Communications: Media and Society from the Evolution of Speech to the Internet (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 27.

- What Can I Do with This Major? “Communication Studies,” accessed May 18, 2012, http://whatcanidowiththismajor.com/major/communication-studies↵