5.3: Cognitive Development in Early Childhood

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 69384

Early childhood is a time of pretending, blending fact and fiction, and learning to think of the world using language. As young children move away from needing to touch, feel, and hear about the world toward learning some basic principles about how the world works, they hold some pretty interesting initial ideas. For example, how many of you are afraid that you are going to go down the bathtub drain? Hopefully, none of you do! But a child of three might really worry about this as they sit at the front of the bathtub. A child might protest if told that something will happen “tomorrow” but be willing to accept an explanation that an event will occur “today after we sleep.” Or the young child may ask, “How long are we staying? From here to here?” while pointing to two points on a table. Concepts such as tomorrow, time, size and distance are not easy to grasp at this young age. Understanding size, time, distance, fact and fiction are all tasks that are part of cognitive development in the preschool years.

Piaget's Preoperational Intelligence

As a refresher: The Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget proposed that children’s thinking progresses through a series of four discrete stages. By “stages,” he meant periods during which children reasoned similarly about many superficially different problems, with the stages occurring in a fixed order and the thinking within different stages differing in fundamental ways. As you may recall, the four stages that Piaget hypothesized were the sensorimotor stage (birth to 2 years), the preoperational reasoning stage (2 to 6 or 7 years), the concrete operational reasoning stage (6 or 7 to 11 or 12 years), and the formal operational reasoning stage (11 or 12 years and throughout the rest of life).

Schema, Assimilation, and Accommodation

Piaget said that children develop schemes or schema to help them understand the world (scheme, schema, schemata - these are all referring to the same thing). Schema means concepts (mental models) that are used to help us categorize and interpret information. By the time children have reached adulthood, they have created schemata for almost everything. When children learn new information, they adjust their schemata through two processes: assimilation and accommodation. First, they assimilate new information or experiences in terms of their current schemata: assimilation is when they take in information that is comparable to what they already know and the schema is not altered. Accommodation describes when they change their schema based on new information. This process continues as children interact with their environment.

For example, 2-year-old Blake learned the schema for dogs because his family has a Labrador retriever. When Blake sees other dogs in his picture books, he says, “Look mommy, dog!” Thus, he has assimilated them into his schema for dogs. One day, Blake sees a sheep for the first time and says, “Look mommy, dog!” Having a basic schema that a dog is an animal with four legs and fur, Blake thinks all furry, four-legged creatures are dogs. When Blake’s mom tells him that the animal he sees is a sheep, not a dog, Blake must accommodate his schema for dogs to include more information based on his new experiences. Blake’s schema for dog was too broad, since not all furry, four-legged creatures are dogs. He now modifies his schema for dogs and forms a new one for sheep.

Sensorimotor, Preoperational, Concrete Operational, and Formal Operational

Like Freud and Erikson, Piaget thought development unfolds in a series of stages approximately associated with age ranges. He proposed a theory of cognitive development that unfolds in four stages: sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational.

The first stage is the sensorimotor stage, which lasts from birth to about 2 years old (infancy). During this stage, children learn about the world through their senses and motor behavior. Young children put objects in their mouths to see if the items are edible, and once they can grasp objects, they may shake or bang them to see if they make sounds. Between 5 and 8 months old, the child develops object permanence, which is the understanding that even if something is out of sight, it still exists (Bogartz, Shinskey, & Schilling, 2000). According to Piaget, young infants do not remember an object after it has been removed from sight. Piaget studied infants’ reactions when a toy was first shown to an infant and then hidden under a blanket. Infants who had already developed object permanence would reach for the hidden toy, indicating that they knew it still existed, whereas infants who had not developed object permanence would appear confused.

Please take a few minutes to view this brief video demonstrating different children’s ability to understand object permanence.

In Piaget’s view, around the same time children develop object permanence, they also begin to exhibit stranger anxiety, which is a fear of unfamiliar people. Babies may demonstrate this by crying and turning away from a stranger, by clinging to a caregiver, or by attempting to reach their arms toward familiar faces such as parents. Stranger anxiety results when a child is unable to assimilate the stranger into an existing schema; therefore, she can’t predict what her experience with that stranger will be like, which results in a fear response.

Piaget’s second stage is the preoperational stage, which is from approximately 2 to 7 years old (early childhood). In this stage, children can use symbols to represent words, images, and ideas, which is why children in this stage engage in pretend play. A child’s arms might become airplane wings as he zooms around the room, or a child with a stick might become a brave knight with a sword. Children also begin to use language in the preoperational stage, but they cannot understand adult logic or mentally manipulate information (the term operational refers to logical manipulation of information, so children at this stage are considered to be pre-operational). Children’s logic is based on their own personal knowledge of the world so far, rather than on conventional knowledge. For example, dad gave a slice of pizza to 10-year-old Keiko and another slice to her 3-year-old brother, Kenny. Kenny’s pizza slice was cut into five pieces, so Kenny told his sister that he got more pizza than she did. Children in this stage cannot perform mental operations because they have not developed an understanding of conservation, which is the idea that even if you change the appearance of something, it is still equal in size as long as nothing has been removed or added.

This video shows a 4.5-year-old boy in the preoperational stage as he responds to Piaget’s conservation tasks.

During this stage, we also expect children to display egocentrism, which means that the child is not able to take the perspective of others. A child at this stage thinks that everyone sees, thinks, and feels just as they do. Imagine a pair of siblings, Keiko and Kenny, what happens when one of them needs to take the perspective of the other? Keiko’s birthday is coming up, so their mom takes Kenny to the toy store to choose a present for his sister. He selects an Iron Man action figure for her, thinking that if he likes the toy, his sister will too. An egocentric child is not able to infer the perspective of other people and instead attributes his own perspective.

Piaget developed the Three-Mountain Task to determine the level of egocentrism displayed by children. Children view a 3-dimensional mountain scene from one viewpoint, and are asked what another person at a different viewpoint would see in the same scene. Watch the Three-Mountain Task in action in this short video from the University of Minnesota and the Science Museum of Minnesota.

Piaget’s third stage is the concrete operational stage, which occurs from about 7 to 11 years old (middle childhood). In this stage, children can think logically about real (concrete) events; they have a firm grasp on the use of numbers and start to employ memory strategies. They can perform mathematical operations and understand transformations, such as addition is the opposite of subtraction, and multiplication is the opposite of division. In this stage, children also master the concept of conservation: Even if something changes shape, its mass, volume, and number stay the same. For example, if you pour water from a tall, thin glass to a short, fat glass, you still have the same amount of water.

Children in the concrete operational stage also understand the principle of reversibility, which means that objects can be changed and then returned back to their original form or condition. Take, for example, water that you poured into the short, fat glass: You can pour water from the fat glass back to the thin glass and still have the same amount (minus a couple of drops).

The fourth, and last, stage in Piaget’s theory is the formal operational stage, which is from about age 11 to adulthood. Whereas children in the concrete operational stage are able to think logically only about concrete events, children in the formal operational stage can also deal with abstract ideas and hypothetical situations. Children in this stage can use abstract thinking to problem solve, look at alternative solutions, and test these solutions. In adolescence, a renewed egocentrism occurs. For example, a 15-year-old with a very small pimple on her face might think it is huge and incredibly visible, under the mistaken impression that others must share her perceptions.

According to Piaget, the highest level of cognitive development is formal operational thought, which develops between 11 and 20 years old. However, many developmental psychologists disagree with Piaget, suggesting a fifth stage of cognitive development, known as the postformal stage (Basseches, 1984; Commons & Bresette, 2006; Sinnott, 1998). In postformal thinking, decisions are made based on situations and circumstances, and logic is integrated with emotion as adults develop principles that depend on contexts. One way that we can see the difference between an adult in postformal thought and an adolescent in formal operations is in terms of how they handle emotionally charged issues.

It seems that once we reach adulthood our problem solving abilities change: As we attempt to solve problems, we tend to think more deeply about many areas of our lives, such as relationships, work, and politics (Labouvie-Vief & Diehl, 1999). Because of this, postformal thinkers are able to draw on past experiences to help them solve new problems. Problem-solving strategies using postformal thought vary, depending on the situation. What does this mean? Adults can recognize, for example, that what seems to be an ideal solution to a problem at work involving a disagreement with a colleague may not be the best solution to a disagreement with a significant other.

Characteristics of the Preoperational Stage

Piaget’s stage that coincides with early childhood is the preoperational stage. The word operational means logical, so these children were thought to be "illogical" (compared to the typical thinking of most older children and adults). However, they were learning to use language or to think of the world symbolically, which is fascinating! Let’s examine some Piaget assertions about children’s cognitive abilities at this age.

Pretend Play

Pretending is a favorite activity at this time. A toy has qualities beyond the way it was designed to function and can now be used to stand for a character or object unlike anything originally intended. A teddy bear, for example, can be a baby or the ruler of a faraway land! Pretend or make-believe shows the child's ability to invent and imagine.

Piaget believed that children’s pretend play helped children solidify new schemes they were developing cognitively. This play, then, reflected changes in their conceptions or thoughts. However, children also learn as they pretend and experiment. Their play does not simply represent what they have learned (Berk, 2007).

Egocentrism

Egocentrism in early childhood refers to the tendency of young children to think that everyone sees things in the same way as the child. Piaget’s classic experiment on egocentrism involved showing children a 3 dimensional model of a mountain and asking them to describe what a doll that is looking at the mountain from a different angle might see. Children tend to choose a picture that represents their own, rather than the doll’s view. However, when children are speaking to others, they tend to use different sentence structures and vocabulary when addressing a younger child or an older adult. This indicates some awareness of the views of others.

Syncretism

Syncretism refers to a tendency to think that if two events occur simultaneously, one caused the other. An example of this would be a child thinking that if she put on her bathing suit it would turn to season to summer.

Animism

Animism refers to attributing life-like qualities to objects. The cup is alive, the chair that falls down and hits the child’s ankle is mean, and the toys need to stay home because they are tired. Watch this segment in which the legendary late actor, Robin Williams, sings a song to teach children the difference between what is alive and what is not alive. (Please note: this video is meant to respectfully honor the incredible work he did in his life as he was certainly one of the most alive humans to grace our hearts with humor). Cartoons frequently show objects that appear alive and take on lifelike qualities. Young children do seem to think that objects that move may be alive but after age 3, they seldom refer to objects as being alive (Berk, 2007).

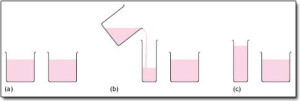

Conservation of Liquid. Does pouring liquid in a tall, narrow container make it have more?

Conservation Errors

Conservation refers to the ability to recognize that moving or rearranging matter does not change the matter - something that can look different and be unchanged in amount or in what it really is. Imagine a 2 year old and a 4 year old eating lunch. The 4 year old has a whole peanut butter and jelly sandwich. He notices, however, that his younger sister’s sandwich is cut in half and protests, “She has more!” Watch the following examples of conversation errors of quantity and volume:

Theory of Mind

Imagine showing a child of three a bandaid box and asking the child what is in the box. Chances are, the child will reply, “bandaids.” Now imagine that you open the box and pour out crayons. If you ask the child what they thought was in the box before it was opened, they may respond, “crayons”. If you ask what their friend would have thought was in the box, the response would still be “crayons”. Why? Before about 4 years of age, a child does not recognize that the mind can hold ideas that are not accurate. So this 3 year old changes their response once shown that the box contains crayons. The theory of mind is the understanding that the mind can be tricked or that the mind is not always accurate. At around age 4, the child would reply, “Crayons” and understand that thoughts and realities do not always match.

This awareness of the existence of mind is part of "social intelligence" or the ability to recognize that others can think differently about situations. It helps us to be self-conscious or aware that others can think of us in different ways and it helps us to be able to be understanding or empathetic toward others. This ability helps us to anticipate and predict the actions of others (even though these predictions are sometimes inaccurate).

Vygotsky

Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) was a Russian psychologist who argued that culture has a major impact on a child’s cognitive development. Piaget and Gesell believed development stemmed directly from the child, and although Vygotsky acknowledged intrinsic development, he argued that it is the language, writings, and concepts arising from the culture that elicit the highest level of cognitive thinking (Crain, 2005). He believed that the social interactions with adults and more learned peers can facilitate a child’s potential for learning. Without this interpersonal instruction, he believed children’s minds would not advance very far as their knowledge would be based only on their own discoveries. Let’s review some of Vygotsky’s key concepts.

Zone of Proximal Development and Scaffolding

Vygotsky’s best known concept is the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). Vygotsky stated that children should be taught in the ZPD, which occurs when they can almost perform a task, but not quite on their own without assistance. With the right kind of teaching, however, they can accomplish it successfully. A good teacher identifies a child’s ZPD and helps the child stretch beyond it. Then the adult (teacher) gradually withdraws support until the child can then perform the task unaided. Researchers have applied the metaphor of scaffolds (the temporary platforms on which construction workers stand) to this way of teaching. Scaffolding is the temporary support that parents or teachers give a child to do a task.

Private Speech

Do you ever talk to yourself? Why? Chances are, this occurs when you are struggling with a problem, trying to remember something, or feel very emotional about a situation. Children talk to themselves too. Piaget interpreted this as egocentric speech or a practice engaged in because of a child’s inability to see things from another’s point of view. Vygotsky, however, believed that children talk to themselves in order to solve problems or clarify thoughts. As children learn to think in words, they do so aloud before eventually closing their lips and engaging in private speech or inner speech.

Thinking out loud eventually becomes thought accompanied by internal speech, and talking to oneself becomes a practice only engaged in when we are trying to learn something or remember something. This inner speech is not as elaborate as the speech we use when communicating with others (Vygotsky, 1962). The APA (American Psychological Association) Dictionary offers the following definition of Private Speech:

spontaneous self-directed talk in which a person “thinks aloud,” particularly as a means of regulating cognitive processes and guiding behavior. In the theorizing of Lev Vygotsky, private speech is considered equivalent to egocentric speech.

Contrast with Piaget

Piaget was highly critical of teacher-directed instruction believing that teachers who take control of the child’s learning place the child into a passive role (Crain, 2005). Further, teachers may present abstract ideas without the child’s true understanding, and instead they just repeat back what they heard. Piaget believed children must be given opportunities to discover concepts on their own. As previously stated, Vygotsky did not believe children could reach a higher cognitive level without instruction from more learned individuals. Vygotsky viewed social interaction as necessary for cognitive development. Who is correct? Both theories certainly contribute to our understanding of how children learn.

(Source - Lally & Valentine French; CC BY-NC-SA)

Language Development

Vocabulary Growth

A child’s vocabulary expands between the ages of 2 to 6 from about 200 words to over 10,000 words through a process called fast-mapping. Words are easily learned by making connections between new words and concepts already known. The parts of speech that are learned depend on the language and what is emphasized. Children speaking verb-friendly languages such as Chinese and Japanese tend to learn nouns more readily. But those learning less verb-friendly languages, such as English (seen as a noun-friendly language), seem to need assistance in grammar to master the use of verbs (Imai, et als, 2008). Children are also very creative in creating their own words to use as labels such as a “take-care-of” when referring to John, the character on the cartoon, Garfield, who takes care of the cat.

Literal Meanings

Children can repeat words and phrases after having heard them only once or twice. But they do not always understand the meaning of the words or phrases. This is especially true of expressions or figures of speech which are taken literally. For example, in a classroom full of preschoolers the teacher says, “Wow! That was a piece of cake!” The children begin asking “Cake? Where is my cake? I want cake!”

Overregularization

Children learn rules of grammar as they learn language but may apply these rules inappropriately at first. For instance, a child learns to add “ed” to the end of a word to indicate past tense. Then form a sentence such as “I goed there. I doed that.” This is typical at ages 2 and 3. They will soon learn new words such as went and did to be used in those situations.

The Impact of Training

Children can be assisted in learning language by others who listen attentively, model more accurate pronunciations and encourage elaboration. The child exclaims, “I’m goed there!” and the adult responds, “You went there? Where did you go?” Children may be ripe for language as Chomsky suggests, but active participation in helping them learn is important for language development as well. The process of assisting through guided support (called scaffolding) is one in which the guide provides needed assistance to the child as a new skill is learned.