12.2: Types of Persuasive Speeches

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 145387

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate among the four types of persuasive claims.

- Understand how the four types of persuasive claims lead to different types of persuasive speeches.

- Explain the two types of policy claims.

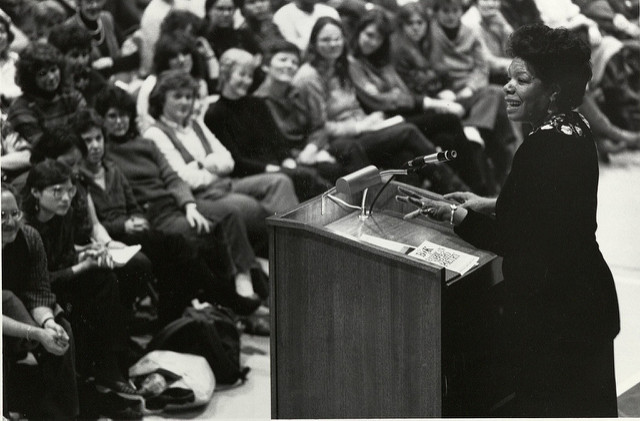

Burns Library, Boston College – Maya Angelou – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Obviously, there are many different persuasive speech topics you could select for a public speaking class. Anything from localized claims like changing a specific college or university policy to larger societal claims like adding more enforcement against the trafficking of women and children in the United States could make for an interesting persuasive speech. You’ll notice in the previous sentence we referred to the two topics as claims. In this use of the word “claim,” we are declaring the goodness or desirability of an attitude, value, belief, or behavior that others may dispute. As a result of the dispute between our perceptions of the desirability of an attitude, value, belief, or behavior and the perceptions of others, we attempt to persuade others by supporting our claim with some sort of evidence and logic. There are four common claims that can be made: definitional, factual, policy, and value.

Definitional Claims

The first type of claim that a persuasive speaker can make is a definitional (or classification) claim. Definitional claims are claims over the denotation or classification of what something is. In essence, we are trying to argue for what something is or what something is not. Most definitional claims fall to a basic argument formula:

Y has features A, B, and C. X is (or is not) a Y because it has (or does not have) features A, B, or C.

For example, maybe you’re trying to persuade your classmates that while therapeutic massage is often performed on nude clients, it is not a form of prostitution. You could start by explaining what therapeutic massage is and then look at the legal definition of prostitution and demonstrate to your peers that therapeutic massage does not fall into the legal definition of prostitution because it does not involve the behaviors characterized by that definition.

Factual Claims

Factual claims set out to argue the truth or falsity of an assertion. Some factual claims are simple to answer: Barack Obama is the first African American President of the United States; the tallest man in the world, Robert Wadlow, was eight feet and eleven inches tall; Facebook wasn’t profitable until 2009. All these factual claims are well documented by evidence and can be easily supported with some research.

However, many factual claims cannot be answered absolutely. It is difficult to determine the truth or falsity of some factual claims because the final answer on the subject has not been discovered (e.g., when does life begin). Probably the most historically interesting and consistent factual claim is the existence of a higher power, God, or other religious deities. The simple fact of the matter is that there is not enough evidence to clearly answer this factual claim in any specific direction.

Other factual claims that may not be easily answered using evidence are predictions of what may or may not happen. For example, you could give a speech on the future of climate change or the future of terrorism in the United States. While there may be evidence that something may happen in the future, you can't actually say with 100% certainty that it will happen in the future.

When thinking of factual claims, it often helps to pretend that you’re putting a specific claim on trial, and as the speaker it is your job to defend your claim as a lawyer would defend a client. Ultimately, your job is to be more persuasive than your audience members who act as both opposition attorneys and judges.

Policy Claims

The third type of persuasive claim is the policy claim—a statement about the nature of a problem and the solution that should be implemented. Policy claims are probably the most common form of persuasive speaking because we are surrounded by problems and people who have ideas about how to fix these problems. Let’s look at a few examples of possible policy claims:

- The United States should stop capital punishment.

- The United States should become independent from the use of foreign oil by allowing more offshore drilling off its coasts.

- The United States should make human cloning for organ donation illegal.

- The U.S. Congress should change sentencing laws so nonviolent drug offenders are sent to rehabilitation centers instead of prison.

- The U.S. Congress should require the tobacco industry to pay 100% of the medical bills for individuals dying of smoking-related cancers.

- The United States should divert the funding from United States Agency for International Development (U.S. AID) to prevent poverty in the United States rather than feeding the starving people around the world.

Each of these claims has a clear perspective that is being advocated. Policy claims will always have a clear and direct opinion on what should occur and what needs to change. When examining policy claims, we generally talk about two different persuasive goals: passive agreement and immediate action.

1) Gain Passive Agreement

When we attempt to gain the passive agreement of our audience, our goal is to get them to agree with our specific policy without asking them to do anything to enact the policy. For example, maybe your speech is on why the Federal Communications Commission should regulate violence on television like it does foul language (i.e., no violence until after 9 p.m.). Your goal as a speaker is to get your audience to agree that it is in our best interest as a society to prevent violence from being shown on television before 9 p.m., but you are not seeking to have your audience run out and call their senators or congressmen or even sign a petition. Often the first step in larger political change is simply getting a large portion of the population to agree with your policy perspective.

Let’s look at a few more passive agreement claims:

- Racial profiling of individuals suspected of belonging to known terrorist groups is a way to make the United States safer.

- Requiring U.S. citizens to “show their papers” is a violation of democracy and resembles the tactics of Nazi Germany and communist Russia.

- Colleges and universities should implement a standardized testing program to ensure student learning outcomes are similar across different institutions.

In each of these claims, the goal is to sway one’s audience to a specific attitude, value, or belief, but not necessarily to get the audience to enact any specific behaviors.

2) Gain Immediate Action

The alternative to passive agreement is immediate action or persuading your audience to start engaging in a specific behavior. Many passive agreement topics can become immediate action topics as soon as you tell your audience what behavior they should engage in (e.g., sign a petition, call a senator, vote). While it is much easier to elicit passive agreement than to get people to do something, you should always try to get your audience to act and do so quickly. A common mistake that speakers make is telling people to do something that will occur in the future. The longer it takes for people to engage in the action you desire, the less likely it is that your audience will engage in that behavior.

Here are some examples of good claims with immediate calls to action:

- College students should eat more fruit, so I am encouraging everyone to eat the apple I have provided you and start getting more fruit in your diet.

- Teaching a child to read is one way to ensure that the next generation will be stronger than those that have come before us, so please sign up right now to volunteer one hour a week to help teach a child to read.

- The United States should reduce its nuclear arsenal by 20 percent over the next five years. Please sign the letter provided encouraging the president to take this necessary step for global peace. Once you’ve signed the letter, hand it to me, and I’ll fax it to the White House today.

Each of these three examples starts with a basic claim and then tags on an immediate call to action. Remember, the faster you can get people to engage in a behavior, the more likely they actually will.

Value Claims

The final type of claim is a value claim, which is a claim where the speaker is making a judgment claim about something (e.g., it’s good or bad, it’s right or wrong, it’s beautiful or ugly, moral or immoral).

Let’s look at three value claims. We’ve italicized the evaluative term in each claim:

- Dating people on the Internet is an immoral form of dating.

- The Lincoln statue in Washington D.C. is ugly.

- It’s unfair for pregnant women to have special parking spaces at malls, shopping centers, and stores.

Each of these three claims could definitely be made by a speaker and other speakers could say the exact opposite. When making a value claim, it’s hard to ascertain why someone has chosen a specific value stance without understanding her or his criteria for making the evaluative statement. For example, if someone finds all forms of technology immoral, then it’s really no surprise that he or she would find Internet dating immoral as well. As such, you need to clearly explain your criteria for making the evaluative statement. For example, when we examine the claim about Lincoln's statue, if your criteria for the term “ugly” is its style of carving or its proportion compared to its location then your evaluative statement can be more easily understood and evaluated by your audience. If, however, you state that your criterion is that Lincoln was a bad person because of what he did to the first nation people of America, then your statement takes on a slightly different meaning. Ultimately, when making a value claim, you need to make sure that you clearly label your evaluative term and provide clear criteria for how you came to that evaluation.

Key Takeaways

- There are four types of persuasive claims. Definition claims argue the denotation or classification of what something is. Factual claims argue the truth or falsity of an assertion being made. Policy claims argue the nature of a problem and the solution that should be taken. Lastly, value claims argue a judgment about something (e.g., it’s good or bad, it’s right or wrong, it’s beautiful or ugly, moral or immoral).

- Each of the four claims leads to different types of persuasive speeches. As such, public speakers need to be aware of the type of claim they are advocating for, in order to understand the best methods of persuasion.

- In policy claims, persuaders attempt to convince their audiences to either passively accept or actively act. When persuaders attempt to gain passive agreement from an audience, they hope that an audience will agree with what is said about a specific policy without asking the audience to do anything to enact that policy. Gaining immediate action, on the other hand, occurs when a persuader gets the audience to actively engage in a specific behavior.

Exercises

- Look at the list of the top one hundred speeches in the United States during the twentieth century compiled by Stephen E. Lucas and Martin J. Medhurst (http://www.americanrhetoric.com/top100speechesall.html). Select a speech and examine the speech to determine which type of claim is being made by the speech.

- Look at the list of the top one hundred speeches in the United States during the twentieth century compiled by Stephen E. Lucas and Martin J. Medhurst and find a policy speech (http://www.americanrhetoric.com/top100speechesall.html). Which type of policy outcome was the speech aimed at achieving—passive agreement or immediate action? What evidence do you have from the speech to support your answer?