10.1: The Genus Homo, The Environment, and Evolution

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 177674

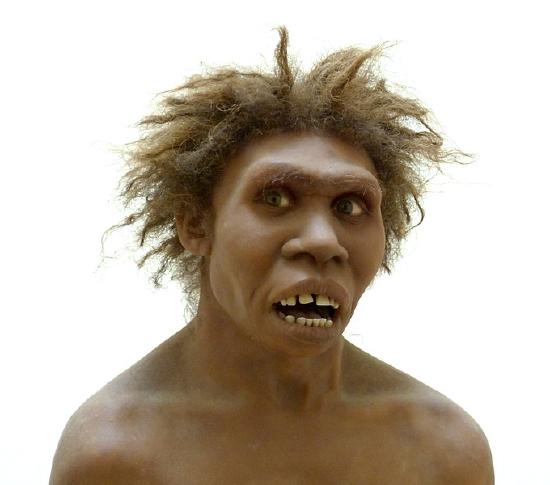

The boy was no older than 9 when he perished by the swampy shores of the lake. After death, his slender, long-limbed body sank into the mud of the lake shallows. His bones fossilized and lay undisturbed for 1.5 million years. In the 1980s, fossil hunter Kimoya Kimeu, working on the western shore of Lake Turkana, Kenya, glimpsed a dark colored piece of bone eroding in a hillside. This small skull fragment led to the discovery of what is arguably the world’s most complete early hominin fossil—a youth identified as a member of the species Homo erectus. Now known as Nariokotome Boy, after the nearby lake village, the skeleton has provided a wealth of information about the early evolution of our own genus, Homo (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). Today, a stone monument with an inscription in three languages—English, Swahili, and the local Turkana language—marks the site of this momentous fossil discovery.

The previous chapter described our oldest human ancestors, primarily members of the genus Australopithecus who lived between 2 million and 4 million years ago. This chapter introduces the earliest members of the genus Homo, focusing on the species Homo habilis and Homo erectus.

DEFINING THE GENUS HOMO

Since our discipline is fundamentally concerned with what makes us human, defining our own genus takes on special significance for anthropologists. The genus is the next level up from species in the classification system originally devised by Carolus Linnaeus. In the 1758 publication Systema Naturae, Linnaeus assigned humans the genus name Homo, meaning “person.” Under this classification scheme, Linnaeus included several ape species, as well as wild children and mythical humans such as cave-dwelling troglodytes. In the present-day classification, the apes and monster people have long been removed, and our species, Homo sapiens, remains as its only living representative. But ever since scientists have acknowledged the existence of extinct species of humans, they have debated which of these display sufficient “humanness” to merit classification in our genus.

When grouping species into a common genus, biologists will consider criteria such as physical characteristics (morphology), evidence of recent common ancestry, and adaptive strategy (use of the environment). However, there is disagreement about which of those criteria should be prioritized, as well as how specific fossils should be interpreted in light of the criteria.

There is general agreement that species classified as Homo should share characteristics broadly similar to our species. These include the following:

- a relatively large brain size, indicating a high degree of intelligence;

- a smaller and flatter face;

- smaller jaws and teeth; and

- increased reliance on culture, particularly the use of stone tools, to exploit a greater diversity of environments (adaptive zone).

Some researchers would include larger overall body size and limb proportions (longer legs/shorter arms) in this list. There is also an apparent decline in sexual dimorphism (body-size differences between males and females). While these criteria seem relatively clear-cut, evaluating them in the fossil record has proved more difficult, particularly for the earliest members of the genus. There are several reasons for this. First, many fossil specimens dating to this time period are incomplete and poorly preserved, making them difficult to evaluate. Second, early Homo fossils appear quite variable in brain size, facial features, and teeth and body size, and there is not yet consensus about how to best make sense of this diversity. Finally, there is growing evidence that the evolution of the genus Homo proceeded in a mosaic pattern: in other words, these characteristics did not appear all at once in a single species; rather, they were patchily distributed in different species from different regions and time periods. Consequently, different researchers have come up with conflicting classification schemes depending on which criteria they think are most important.

In this chapter, we will take several pathways toward examining the origin and evolution of the genus Homo. First, we will explore the environmental conditions of the Pleistocene epoch in which the genus Homo evolved. Next we will examine the fossil evidence for the two principal species traditionally identified as early Homo: Homo habilis and Homo erectus. Then we will use data from fossils and archaeological sites to reconstruct the behavior of early members of Homo, including tool manufacture, subsistence practices, migratory patterns, and social structure. Finally, we will consider these together in an attempt to characterize the key adaptive strategies of early Homo and how they put our early ancestors on the trajectory that led to our own species, Homo sapiens.

CLIMATE CHANGE AND HUMAN EVOLUTION

A key goal in the study of human origins is to learn about the environmental pressures that may have shaped human evolution. As indicated in Chapter 7, scientists use a variety of techniques to reconstruct ancient environments. These include stable isotopes, core samples from oceans and lakes, windblown dust, analysis of geological formations and volcanoes, and fossils of ancient plant and animal communities. Such studies have provided valuable information about the environmental context of early Homo.

The early hominin species covered previously, such as Ardipithecus ramidus and Australopithecus afarensis, evolved during the late Pliocene epoch. The Pliocene (5.3 million to 2.6 million years ago) was marked by cooler and drier conditions, with ice caps forming permanently at the poles. Still, Earth’s climate during the Pliocene was considerably warmer and wetter than at present.

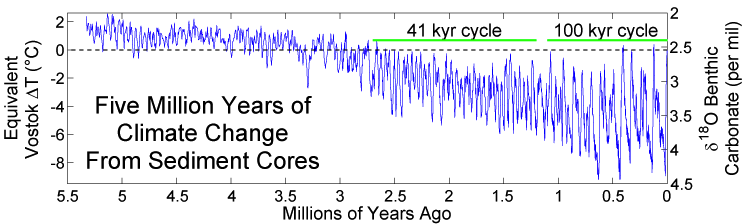

The subsequent Pleistocene epoch (2.6 million years to 11,000 years ago) ushered in major environmental change. The Pleistocene is popularly referred to as the Ice Age. Since the term “Ice Age” tends to conjure up images of glaciers and woolly mammoths, one would naturally assume that this was a period of uniformly cold climate around the globe. But this is not actually the case. Instead, climate became much more variable, cycling abruptly between warm/wet (interglacial) and cold/dry (glacial) cycles. The climate pattern was likely influenced by changes in Earth’s elliptical orbit around the sun. As is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\), each cycle averaged about 41,000 years during the early Pleistocene; the cycles then lengthened to about 100,000 years starting around 1.25 million years ago. Since mountain ranges, wind patterns, ocean currents, and volcanic activity can all influence climate pattern, climate change had extreme effects on the environment in some regions but less effects on others.

Definition: Pleistocene

Geological epoch dating from 2.6 million years ago to about 11,000 years ago.

For a present-day example with which you might be familiar, consider the El Niño weather pattern. This is where warming of the Pacific Ocean in the equator region influences rainfall, hurricane frequency, and other weather activity in different parts of the world. During El Niño years, some areas get more rainfall than average and some get less. A recent El Niño in 2017 produced catastrophic flooding along the Peruvian coast, and one in 2015 led to drought and severe bushfires in Australia. If El Niños, despite being a predictable and well-known occurrence, can cause so much disruption to our technologically advanced society, imagine how vulnerable our ancestors must have been to climate change. An adaptive strategy that could buffer against this kind of uncertainty would have been extremely valuable.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Temperature estimates during the last five million years, extrapolated from deep-sea core data. Note both the lower temperatures and the increased temperature oscillations starting at 2.6 million years ago, the start of the Pleistocene epoch. Glacial/interglacial cycles during the early part of the epoch are shorter, each averaging about 41,000 years.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Temperature estimates during the last five million years, extrapolated from deep-sea core data. Note both the lower temperatures and the increased temperature oscillations starting at 2.6 million years ago, the start of the Pleistocene epoch. Glacial/interglacial cycles during the early part of the epoch are shorter, each averaging about 41,000 years.Data on ancient geography and climate help us understand how our ancestors moved and migrated to different parts of the world, and the constraints under which they operated. When periods of global cooling dominated, sea levels were lower as more water was captured as glacial ice. This exposed continental margins and opened pathways between land masses. During glacial periods, the large Indonesian islands of Sumatra, Java, and Borneo were connected to the Southeast Asian mainland, while New Guinea was part of the southern landmass known as greater Australia. There was a land bridge connection between Britain and continental Europe, and an icy, treeless plain known as Beringia connected Northern Asia and Alaska. At the same time, glaciation made some northern areas inaccessible to human habitation. For example, there is evidence that hominin species were in Britain 950,000 years ago, but it does not appear that Britain was continuously occupied during this period. These early humans may have died out or been forced to abandon the region during glacial periods.

In Africa, paleoclimate research has determined that grasslands (shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)) expanded and shrank multiple times during this period, even as they expanded over the long term (deMenocal 2014). From studies of fossils, paleontologists have been able to reconstruct Pleistocene animal communities and to consider how they were affected by the changing climate. Among the African animal populations, the number of grazing animal species such as antelope increased. Since our early ancestors were also part of this animal community, it is informative to consider how climate change caused changes in the home ranges and migration patterns of animals. Although the African and Eurasian continents are connected by land, the Sahara desert and the mountainous topography of North Africa serve as natural barriers to crossing. But the fossil record shows that animal species moved back and forth between Africa and Eurasia during the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs. During the early Pleistocene, there is evidence of African mammal species such as baboons, hippos, antelope, and African buffalo migrating out of Africa into Eurasia during periods when drier conditions extended out from Africa into the Middle East (Belmaker 2010).

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): A savanna grassland in East Africa. Habitats such as this were becoming increasingly common during the Pleistocene.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): A savanna grassland in East Africa. Habitats such as this were becoming increasingly common during the Pleistocene.This changing environment was undoubtedly challenging for our ancestors, but it offered new opportunities for hominins to make a living. One solution adopted by some hominins was to specialize in feeding on the new types of plants growing in this landscape. As discussed in the previous chapter, the robust australopithecines probably developed their large molar teeth with thick enamel in order to exploit this particular dietary niche. Chemical analyses of robust australopith teeth show an isotopic signature of a diet where grasses and sedges are prominent, such as papyrus.

Members of the genus Homo took a different route. Faced with the unstable African climate and shifting landscape, they evolved bigger brains that enabled them to rely on cultural solutions such as crafting stone tools that opened up new foraging opportunities. This strategy of behavioral flexibility served them well during this unpredictable time and led to new innovations such as increased meat-eating, cooperative hunting, and the exploitation of new environments outside Africa.

REFERENCES

Belmaker, Miriam. 2010. “Early Pleistocene Faunal Connections between Africa and Eurasia: An Ecological Perspective.” In Out of Africa I: The First Hominin Colonization of Eurasia, edited by John G. Fleagle, John J. Shea, Frederick E. Grine, Andrea L. Baden, and Richard E. Leakey, 183–205. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

deMenocal, Peter B. 2014. “Climate Shocks.” Scientific American 311 (3): 48–53.

FIGURE ATTRIBUTIONS

Figure \(\PageIndex{1a}\) KNM-WT 15000 Turkana Boy Skeleton by Smithsonian [exhibit: Human Evolution Evidence, Human Fossils, Fossils, KNM-WT 15000] is copyrighted and used for educational and non-commercial purposes as outlined by the Smithsonian.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1b}\) MNP – Turkanajunge 2 by Wolfgang Sauber (photograph) and E. Daynes (sculpture) is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 License.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) Five Myr Climate Change by Dragons flight (Robert A. Rohde), based on data from Lisiechi and Raymo (2005), is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 License.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) Savanna grasslands of East Africa by International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI)/Elsworth is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 License.