12.1: Defining Modernity

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 177717

The walls of a pink limestone cave exposed to the outside world in the hillside of Jebel Irhoud jutted out of the otherwise barren landscape of the Moroccan desert (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). The year was 2007 and it turned out to be a momentous occasion for science. A fossil unearthed by a team of researchers was barely visible to the untrained eye. Just the fossil cranium’s robust brows were peering out of the rock. The find was welcome but not sheer luck: Hominin fossils have been found here since their first accidental discovery by miners in 1960. This research team from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology was just the latest to explore the prehistoric human presence in this part of North Africa. Excavating near the first discovery, the researchers wanted to learn more about how Homo sapiens lived far from East Africa, where we thought our species originated.

The scientists were surprised when they analyzed the cranium, named Irhoud 10, and other fossils. Statistical comparisons with other human crania concluded that the Irhoud face shapes were typical of recent modern humans while the braincases matched ancient modern humans. Based on the findings of other scientists, the team expected these modern Homo sapiens fossils to be around 200,000 years old. Instead, dating revealed that the cranium had been buried for around 315,000 years.

Together, the modern-looking facial dimensions and the older date changed the interpretation of our species, modern Homo sapiens. Our key evolutionary changes from the archaic Homo sapiens of the previous chapter to our species today happened 100,000 years earlier than what we had thought. In addition, the new information suggests that our home region covered more of the vast African continent instead of being concentrated in the east.

This big addition to the study of modern Homo sapiens is just one of the latest in this continually advancing area of biological anthropology. Researchers are continually discovering amazing fossils and ingenious ways to collect data and test hypotheses about our past. Through the collective work of scientists, including archaeologists, geneticists, and anatomists, we are building an overall theory or explanation of modern human origins. We will first cover the skeletal changes from archaic Homo sapiens to modern Homo sapiens. Next, we will track how modern Homo sapiens expanded the range of its species around the world. Lastly, we will cover the development of agriculture and how it changed human culture to how we practice it today.

DEFINING MODERNITY

What defines a modern Homo sapiens when compared to an archaic Homo sapiens, like the ones in the previous chapter? Modern humans, like you and me, have a set of derived traits that are not seen in archaic humans or any other hominin. As with other transitions in hominin evolution, such as increasing brain size and bipedal ability, modern traits do not appear fully formed or all at once. In other words, the first modern Homo sapiens was not just born one day from archaic parents. The traits common to modern Homo sapiens appeared in a mosaic manner: gradually and out of sync with one another. There are two areas to consider when tracking the complex evolution of modern human traits. One is the physical change in the skeleton. The other is behavior inferred from the cranium and material culture.

Definition: mosaic

Composed from a mix or composite of traits.

Skeletal Traits

The skeleton of a modern Homo sapiens is less robust than that of an archaic Homo sapiens. In other words, the modern skeleton is gracile, meaning that the structures are thinner and smoother. Differences related to gracility in the cranium are seen in the braincase, the face, and the mandible. There are also broad differences in the rest of the skeleton.

Cranial Traits

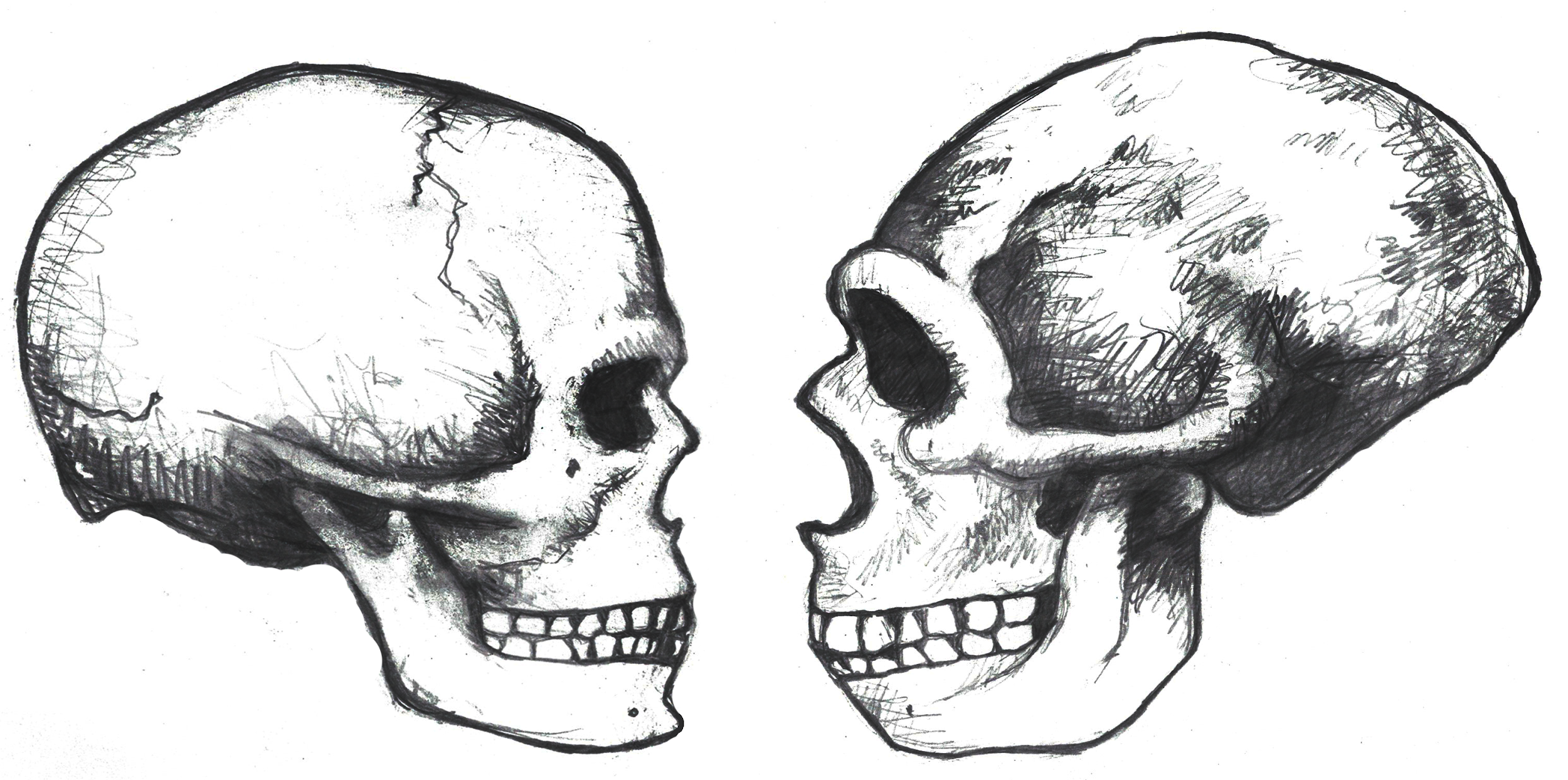

Several elements of the braincase differ between modern and archaic Homo sapiens. Overall, the shape is much rounder, or more globular, on a modern skull (Lieberman, McBratney, and Krovitz 2002; Neubauer, Hublin, and Gunz 2018; Pearson 2008) (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). You can feel the globularity of the modern human skull on the example built into you. Feel the height of your forehead with the palm of your hand. Viewed from the side, the tall vertical forehead of a modern Homo sapiens stands out when compared to the sloping archaic version. This is because the frontal lobe of the modern human brain is larger than the one in archaic humans, and the skull has to accommodate the expansion. The vertical forehead reduces a trait that is common to all other hominins: the brow ridge or supraorbital torus. The sides of the braincase also exhibit changes associated with the globular expansion of the brain: the parietal lobes of the brain and the matching parietal bones of the skull both bulge outward more in modern humans. At the back of the skull, the archaic occipital bun is no longer present. Instead, the occipital region of the modern human cranium has a derived tall and smooth curve, again reflecting the globular brain inside. The different priorities in brain regions may also indicate cognitive and behavioral differences between archaic humans and modern humans, discussed in the next section.

Definition: globular

Having a rounded appearance. Increased globularity of the braincase is a trait of modern Homo sapiens.

Definition: supraorbital torus

The bony brow ridge across the top of the eye orbits on many hominin crania.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Comparison between modern (left) and archaic (right) Homo sapiens skulls. Note the overall gracility of the modern skull, as well as the globular braincase.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Comparison between modern (left) and archaic (right) Homo sapiens skulls. Note the overall gracility of the modern skull, as well as the globular braincase.The trend of shrinking face size across hominins reaches its extreme with our species as well. The facial bones of a modern Homo sapiens are extremely gracile compared to all other hominins (Lieberman, McBratney, and Krovitz 2002). One specific dimension to compare is the thickness of the zygomatic arches, or cheekbones. As with the shrinking of the face leading up to our species, the decreasing reliance on needing large teeth for survival may have been the reason that modern human faces are so gracile in comparison to other humans. Continuing a trend in hominin evolution, technological innovations kept reducing the importance of teeth in reproductive success (Lucas 2007). As natural selection favored smaller and smaller teeth, the surrounding bone holding these teeth also shrank.

Connected to the face, the mandible is also gracile in modern humans when compared to archaic humans and other hominins. Interestingly, our mandibles have pulled back so far from the prognathism of earlier hominins that we gained an extra structure at the most anterior point, called the mental eminence. You know this structure as the chin: trace your own chin and feel how it curves forward before swooping posteriorly toward your neck. At the skeletal level, it resembles an upside-down “T” at the centerline of the mandible (Pearson 2008). If you look back at illustrations of other hominins, you will see that they all lack a chin. Instead, their mandibles curve straight back without a forward point. What is the chin for and how did it develop? Flora Gröning and colleagues (2011) found evidence of the chin’s importance by simulating physical forces on computer models of different mandible shapes. Their results showed that the chin acts as structural support to withstand strain on the otherwise gracile mandible. In other words, as natural selection favored smaller dentition, the chin developed to maintain structural integrity of the mandible.

Definition: mental eminence

The chin on the mandible of modern H. sapiens. One of the defining traits of our species.

Post-Cranial Gracility

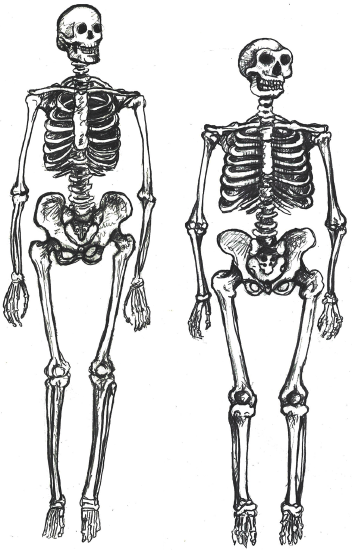

The rest of the modern human skeleton is also more gracile than its archaic counterpart. The differences are clear when comparing a modern Homo sapiens with a cold-adapted Neanderthal (Sawyer and Maley 2005), but the trends are still present when comparing modern and archaic humans within Africa (Pearson 2000). Overall, a modern Homo sapiens post-cranial skeleton has thinner cortical bone, smoother features, and more slender shapes when compared to archaic Homo sapiens (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). For example, the modern pelvis has gracile features along its surface and is narrower in overall width. Our elbow and knee joint surfaces are also narrower. Even the individual fingers and toes are more slender in modern humans. Comparing whole skeletons, modern humans have longer limb proportions relative to the length and width of the torso, giving us lankier outlines.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Anterior views of modern (left) and archaic (right) Homo sapiens skeletons. The modern human has an overall gracile appearance at this scale as well.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Anterior views of modern (left) and archaic (right) Homo sapiens skeletons. The modern human has an overall gracile appearance at this scale as well.As with the cranial traits, we have to consider the evolutionary process behind postcranial gracility. Why is our skeleton so gracile compared to those of other hominins? Natural selection can drive the gracilization of skeletons in several ways (Lieberman 2015). A slender frame is adapted for the efficient long-distance running ability that started with Homo erectus. Furthermore, slenderness is a genetic adaptation for cooling an active body in hotter climates, which aligns with the ample evidence that Africa was the home continent of our species.

BEHAVIORAL MODERNITY

Aside from physical differences in the skeleton, researchers have also tracked clues of behavioral changes from archaic to modern humans. From the anthropology of our species today, we know that we practice a very complex version of culture, with many layers to our language, art, social organization, and technology, among other areas. Did cultural complexity increase gradually or quickly with the first modern humans? This question is being actively investigated. A major obstacle to answering this question is that it is hard to define and measure cultural complexity. Since we cannot directly observe humans of the distant past, we have to infer these measures of human behavior from other types of evidence. Two particularly illuminating areas are archaeology and the analysis of reconstructed brains.

Archaeology tells us much about the behavioral complexity of past humans by interpreting the significance of material culture. In terms of evolved advanced culture, items created with an artistic flair, or as a decorative piece, speak of some abstract thought process (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). The demonstration of difficult artistic techniques and technological skills hints at social learning and cooperation as well. For example, most of your skills were taught to you by a more experienced person, upon which you’ve developed your own style with practice. Some day you may pass on what you know to someone else using language to convey your knowledge. The same process is believed to have happened with early modern humans in areas such as toolmaking and craftwork, producing the sophisticated material culture that we can now study. According to paleoanthropologist John Shea (2011), one way to track the complexity of past behavior through artifacts is by measuring the variety of tools found together. The more types of tools constructed with different techniques and for different purposes, the more modern the behavior. Turning this view to ourselves, think of all of the tools we have available to us today at a typical hardware store and the cumulative knowledge they represent. This idea of measuring past behavior is promising, but researchers are still working on an archaeological way to measure cultural complexity that is useful across time and place.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Carved ivory figure called the Lion-Man of the Hohlenstein-Stadel. It dates to the Aurignacian culture, between 35 and 40 kya. What does this artifact suggest about the culture and technical skill of its artist?

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Carved ivory figure called the Lion-Man of the Hohlenstein-Stadel. It dates to the Aurignacian culture, between 35 and 40 kya. What does this artifact suggest about the culture and technical skill of its artist?The interpretation of brain anatomy is another promising approach to studying the evolution of human behavior. When looking at the body of work on this topic in modern Homo sapiens brains, researchers found a weak association between brain size and test-measured intelligence (Pietschnig et al. 2015). This means that there are more significant factors that affect tested intelligence than just brain size. Additionally, they found no association between intelligence and biological sex. Since the sheer size of the brain is not useful for weighing intelligence, paleoanthropologists are instead investigating the differences in certain brain structures. The differences in organization between modern Homo sapiens brains and archaic Homo sapiens brains may reflect different cognitive priorities that account for modern human culture. Researchers (e.g., Bruner 2010) have hypothesized that the expanded frontal and parietal lobes in the globular modern human braincases mean that we can do more complex thinking regarding memory and social ability than the Neanderthals could. In contrast, the Neanderthal brain prioritized the visual regions where the occipital bun was located, with fewer neurons in the frontal area for complex thinking. As with the archaeological line of research in the preceding paragraph, this is a very active area of investigation. New discoveries will refine what we know about the human brain and apply that knowledge to studying the distant past.

Taken together, the cognitive abilities in modern humans may have translated into an adept use of tools to enhance survival. The ability to process a new environment, adapt to it with innovative technology, and pass on that knowledge may be the key behind the success of modern Homo sapiens. Researchers Patrick Roberts and Brian A. Stewart call this concept the generalist-specialist niche: Our species is an expert at living in a wide array of environments, with populations culturally specializing in their own particular surroundings (Roberts and Stewart 2018). The next section tracks how far around the world these skeletal and behavioral traits have taken us.

Definition: generalist-specialist niche

The ability to survive in a variety of environments by developing local expertise. Evolution toward this niche may have been what allowed modern Homo sapiens to expand past the geographical range of other human species.

REFERENCES

Bruner, Emiliano. 2010. “Morphological Differences in the Parietal Lobes within the Human Genus.” Current Anthropology 51 (S1): S77–S88.

Gröning, Flora, Jia Liu, Michael J. Fagan, and Paul O’Higgins. 2011. “Why Do Humans Have Chins? Testing the Mechanical Significance of Modern Human Symphyseal Morphology with Finite Element Analysis.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 144 (4): 593–606.

Lieberman, Daniel E. 2015. “Human Locomotion and Heat Loss: An Evolutionary Perspective.” Comprehensive Physiology 5 (1): 99–117.

Lieberman, Daniel E., Brandeis M. McBratney, and Gail Krovitz. 2002. “The Evolution and Development of Cranial Form in Homo sapiens.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99 (3): 1134–1139.

Lucas, Peter W. 2007. “The Evolution of the Hominin Diet from a Dental Functional Perspective.” In Evolution of the Human Diet: The Known, the Unknown, and the Unknowable, edited by Peter S. Ungar, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Neubauer, Simon, Jean-Jacques Hublin, and Philipp Gunz. 2018. “The Evolution of Modern Human Brain Shape.” Science Advances 4 (1): eaao5961.

Pearson, Osbjorn M. 2000. “Postcranial Remains and the Origin of Modern Humans.” Evolutionary Anthropology 9: 229–247.

Pearson, Osbjorn M.. 2008. “Statistical and Biological Definitions of ‘Anatomically Modern’ Humans: Suggestions for a Unified Approach to Modern Morphology.” Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 17 (1): 38–48.

Pietschnig, Jakob, Lars Penke, Jelte M. Wicherts, Michael Zeiler, and Martin Voracek. 2015. “Meta-Analysis of Associations between Human Brain Volume and Intelligence Differences: How Strong Are They and What Do They Mean?” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 57: 411–432.

Roberts, Patrick, and Brian A. Stewart. 2018. “Defining the ‘Generalist-Specialist’ Niche for Pleistocene Homo sapiens.” Nature Human Behaviour 2: 542–550.

Sawyer, G. J., and Blaine Maley. 2005. “Neanderthal Reconstructed.” The Anatomical Record (Part B: New Anat.) 283 (1): 23–31.

Shea, John J. 2011. “Refuting a Myth about Human Origins.” American Scientist 99 (2): 128.

FIGURE ATTRIBUTIONS

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) View looking south of the Jebel Irhoud (Morocco) site by Shannon McPherron, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology Leipzig, is used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 License.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) Modern human and Neanderthal original to Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology by Mary Nelson is under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) Modern and archaic Homo sapiens skeletons original to Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology by Mary Nelson is under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) Loewenmensch1 by Dagmar Hollmann is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 License.