17.2: Dissemination and Implementation

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 154290

- Leonard A. Jason, Olya Glantsman, Jack F. O'Brien, and Kaitlyn N. Ramian (Editors)

- DePaul University via Rebus

Chapter Eighteen Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Know the reasons why “validated” and “effective” interventions are often never used

- Identify effective ways to put research finding to use in order to improve health

- Understand advantages of participatory methods that provide more equitable engagement in the creation and use of scientific knowledge

What if our research on bringing about change was not used by society to deliver better services to others? In other words, if all the programs and interventions that have been reviewed in this book were never used by others, this would be tragic. Well, two major publications from about 20 years ago highlighted this problem of getting the public to use programs that have been validated by research.

The first influential report from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) showed that US healthcare was of low quality (IOM, 2001). So you might ask, why haven’t programs that have been shown to work and are effective been widely implemented throughout our healthcare system? We need to find answers to this question as we all have a stake in getting the most effective and safe healthcare interventions. When this IOM report was released, everyone was shocked to learn how the US healthcare system fell short of national goals for quality programs being used by the public.

There are long delays between scientific discovery and use of research findings in communities.These healthcare quality concerns were followed by a second report that showed it took an average of 17 years of science before an effective health practice program reached patients (Balas & Boren, 2000). Even more depressing, at the end of the 17 years, adoption of these practices only occurred among 15% of providers. Imagine, the healthcare you should be getting at age 20 may not reach you until you are 37 years old! And of course, that’s only if you are the lucky one out of six patients (the 15%) whose healthcare is guided by research. Based on these findings, researchers began to focus on the gap between research evidence and healthcare practices.

Ten years after the original IOM report appeared, Health Affairs, an influential journal, published new research on the “quality chasm.” And now, after 20 years, researchers are still finding that their discoveries are not used (Brownson, Proctor, & Colditz, 2018). These high impact findings led to the development of a new field called implementation science. Read more about implementation science here.

Implementation science began because health practices, programs, and policies were not achieving their expected benefits based on their research evidence. When research shows that a treatment works, or a program addresses a problem, we want to realize those benefits in the broader world. In other words, we need to find ways to get effective practices used (or implemented) outside of research studies. Dissemination is the process by which this valuable information is made available for our use. But before we come up with solutions to this dissemination problem, let’s first review the different types of evidence, by which programs are evaluated.

WHAT IS KNOWLEDGE AND EVIDENCE?

Scientists often differentiate types of evidence. Efficacy trials (Type I evidence) are often a first step in program development. These trials establish the cause and effect of a program on its intended outcomes. Efficacy trials determine whether a program changes a health outcome under scientifically controlled conditions. Individuals connected to a university often implement these studies. The next step in developing research evidence is typically known as effectiveness trials. This Type II evidence evaluates cause and effect in community settings, and in these studies the people, such as a teacher in a school, implementing the studies are often right from the community setting. So, what has been learned by well-trained researchers from the university is now implemented from people in the field to see if positive effects are once again found. Evidence-based practices are identified through a series of efficacy and effectiveness studies published in peer-reviewed literature. The third type of evidence (Type III evidence) evaluates the implementation context, such as an organization’s readiness to implement a new practice. One community might be ready and interested to implement a program on birth control, for example, whereas another community might not want to even try to do something in this area due to a number of issues, including the controversies that surround this topic or even lack of leadership to take on such a topic. The readiness of the community is a factor that community psychologists point to as key in whether or not an intervention is successfully implemented (Scaccia et al., 2015). An important skill is being able to work with communities differently so that we take into consideration their readiness to implement an intervention.

Community psychologists often link imbalances in resource allocation to social problems. But even in the creation and distribution of the research knowledge, there might be inequitable practices. For example, some say that we should only rely on knowledge created during randomized clinical trials, as this is the best way to know whether an intervention is effective. Many members of the community, however, do not have access to the resources or skills to implement these types of expensive interventions. And more to the point, there might be many other ways to understand whether an intervention is effective. There is an important role that community members might play in the creation of knowledge. The creation of collaborative teams involving researchers and community members might be one way that allows information to be actually perceived as valuable, and then widely disseminated. We will come back to this important issue, but first let’s see how the field of Community Psychology has come up with some strategies to overcome these dissemination problems mentioned at the start of this chapter.

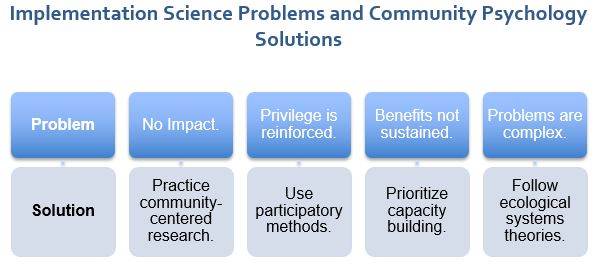

SolutionS TO A COMPLEX PROBLEM

Many people still believe that research knowledge moves efficiently from the research setting (e.g., University) to the community. But this is not always the case. Community psychologists Wandersman and Florin (2003) have examined the gap between research and practice, and they identified a number of the issues that need to be addressed if we are going to effectively deal with the ongoing challenge of putting research to use. It is unfortunate, but just showing that an intervention can improve health does not mean others in society will use those exciting ideas. In other words, just because there is evidence that a particular intervention can solve a health problem, there is no guarantee that it will be adopted by community members and groups. For example, many people might never even get a chance to learn about such an innovation, or the intervention could be poorly implemented so its effectiveness is compromised. Clearly, getting effective programs to be used by others is a complex process, and there are often multiple barriers that need to be addressed. Case Study 18.1 shows a real example of community psychologists addressing these types of implementation issues.

Case Study 18.1

The Veterans Health Administration

The Veterans Health Administration is the largest, integrated US healthcare system. For over 15 years, the Veterans Administration trained thousands of providers to deliver evidence-based addiction and mental healthcare. The Veterans Administration mandates evidence-based care and offers financial incentives for meeting quality measures. Yet, like most US healthcare services, only 3-28% of the Veterans Administration patient population receives the highest quality care. Understanding this limited reach of evidence-based practices is critical to the Veterans Administration policymakers, providers, Veterans, and their families.

To address this problem, Lindsey Zimmerman and her research team of community psychologists used a partnership approach to equitably involve the Veterans Administration stakeholders in implementation research. The program, Modeling to Learn, was designed according to Community Psychology values, methods, principles, and theories. They sought to develop a systems understanding of the Veterans Administration addiction and mental health services. This occurred by empowering frontline providers to improve the limited reach of evidence-based care with their existing staff and local resources (Zimmerman et al., 2016). They prioritized participatory learning, so frontline staff could better meet the needs of their local veteran communities and sustain improvements over time. They also developed and implemented effective methods to address complex problems with care coordination, medication management, psychotherapy, and the overall mix that services teams offer to reduce impairment, relapse, overdose, and suicide.

Preliminary research findings indicate that this innovative program called Modeling to Learn significantly increased the number of patients who received evidence-based care in the Veterans Administration. One important way to increase the chances that research findings like in the case study above will be used, is to be involved in Community Psychology participatory methods, as we will illustrate in the next section. These approaches emphasize more equitable engagement by citizens and scientists in the creation and use of scientific knowledge. When this occurs, it is more likely that effective interventions and improvements will be available.

COMMUNITY PSYCHOLOGY PARTICIPATORY APPROACHES

Community Psychology began when psychologists saw a better way to address some of the most pressing needs and challenges within their communities (see Chapter 1; Jason, Glantsman, O’Brien, & Ramian, 2019). As indicated throughout this book, participatory research methods are a core strategy used by community psychologists (Jason et al., 2004), and they can be effectively used to address implementation problems.

More and more researchers have learned from the field of Community Psychology to bring in community representation in early stages of research. Figure 1 of the National Institute for Drug Abuse Prevention Research Cycle above depicts the need for community input to inform all steps of research development (Robertson, et al., 2012). The NIDA research cycle allows for opportunities to include community input and address contextual factors (dashed lines) earlier in research as opposed to the tendency to use input later (solid lines). Researchers should pursue knowledge of how community factors will impact program implementation and success. The community-centered approach to implementation is community-driven. With a community-centered approach, community psychologists can ensure that their efforts in health, education, practice, policy, and/or research are actually used, as is indicated in Case Study 18.2.

Case Study 18.2

The Infectious Disease Elimination Act Exchange

The Test and Treat Rapid Access Model is designed to start someone who is diagnosed with HIV on Antiretroviral medications immediately. Angela Mooss and her team from Behavioral Science Research Institute partnered with the Infectious Disease Elimination Act Needle Exchange in Miami-Dade County, Florida, to implement this model for their clients in collaboration with community partners (e.g., HIV treatment providers). The needle exchange clientele were active injection drug users who received support to reduce the harm associated with drug use. Although Test and Treat was effectively practiced in Miami with multiple community-based organizations, the Infectious Disease Elimination Act Needle Exchange staff had concerns about their ability to use Test and Treat to link their clientele to HIV care.

Although the Test and Treat model was a best practice, effective use required addressing barriers to implementation so that it could benefit the needle exchange’s clientele. So, what did the Infectious Disease Elimination Act Needle Exchange staff do to put Test and Treat into practice? They used community-centered values and participatory methods to develop their implementation plan. A consumer, Jane Doe, helped with planning from the first meeting and identified key barriers that could have gone unnoticed and impacted the program’s success. Jane pointed out that given the timeframe, individuals who are active injection drug users would experience a “come down” during the Test and Treat process. Even with a care navigator, this would make them more likely to leave mid-way rather than complete enrollment. This would minimize the program’s effectiveness linking vulnerable individuals to life-saving treatment. Read more about the Infectious Disease Elimination Act Needle Exchange program here.

By engaging consumer voices and valuing the expertise of their community, the needle exchange staff prevented a failed implementation and they continue fine-tuning the process with ongoing feedback. As a result, the Infectious Disease Elimination Act Needle Exchange staff have found ways to make services more accessible. This includes Medication Assisted Treatment for individuals willing to begin treatment for opioid use, and the provision of Telehealth services so consumers can enroll directly in Test and Treat from the Infectious Disease Elimination Act Needle Exchange hub. Jane Doe’s voice and expertise were highly valued, and this again shows how community psychologists can partner with community members from the very beginning of their work to have programs more effectively implemented.

Program Adaptation

Successful implementation means that programs often need to be adapted to meet the special needs of the local community, whether they are care managers, foster parents, nurses, teachers, therapists, or physicians. One key question is how much a program needs to be adapted to fit with the local context (adaptation) versus how much it needs to be implemented as intended by developers (fidelity). Fidelity often declines when a program or practice developed under tightly controlled research conditions is then translated to a new community setting. There is some evidence that the closer the community members can implement the programs in ways similar to those of the researchers, the more positive are the health benefits.

However, fidelity and adaptation need not be at odds. For example, Anyon and colleagues (2019) argue that when adaptations follow some key guiding principles, successful fidelity and adaptation can be achieved (Spoth et al., 2013). If there is a core effective method in an innovation, and it is culturally tailored to a particular community, there is no reason it might not be as effective or even more effective than the original intervention. The key issue is whether the intervention continues to have those basic components that are effective and whether it is implemented in a way to which the community members are receptive. Participatory methodologies bridge the research and practice gap through a mutual flow of knowledge among researchers and communities. This bidirectional knowledge sharing goes on throughout the implementation and evaluation phases of the project.

CAPACITY BUILDING

However, there is another problem that often arises: even when a new program is adopted and used in a setting, it is not sustained. This sometimes occurs because the community has not been provided the means and training to take over the intervention. Here we can rely on another Community Psychology principle which involves building capacities for local communities to sustain their efforts over time.

In Chapter 7, Wolfe (2019) reviewed practice competencies that are used by community psychologists. Community capacity building is one of the key practice competencies to sustain the benefits of research and practice efforts. Capacity building describes activities that build tangible resources, such as a prevention program, and enable the community to sustain it. Capacity building helps to maintain staff, facilities, and other resources to deliver effective programs over time, especially when research funding ends (Brownson et al., 2018). Capacity building activities include developing a communications strategy, establishing a fund-raising plan, improving data collection and measurement systems, training, and strategic planning. Community psychologists are trained for community leadership and mentoring, facilitating small and large group processes, consultation, and resource and organizational development (Dalton & Wolfe, 2012). All of these competencies support community and organizational capacity building. By using community-centered processes to build community capacities, community psychologists help community members gain access to important resources. Learn more about an example of community-centered processes by visiting the “Power Through Partnerships” Community Based Participatory Research toolkit for domestic violence researchers. These types of empowering processes lay the groundwork for achieving desired outcomes and sustainability, as is indicated in Case Study 18.3.

Case Study 18.3

Children’s Trust of South Carolina

Children’s Trust of South Carolina (Children’s Trust) is a statewide nonprofit organization focused on the prevention of abuse and neglect. The vision of Children’s Trust is a South Carolina free from child abuse and neglect. The mission of Children’s Trust is to build strong families and empower communities to prevent child abuse by supporting and delivering programs, building coalitions, providing resources, and leading prevention training.

Children’s Trust is considered an intermediary organization, which means that it does not provide direct services, but partners with community-based organizations across the state, who do provide community services. As an intermediary, Children’s Trust performs five core functions: partnership engagement and communications, implementation support, research and evaluation, workforce development, and policy and finance. These functions form the foundation of the Children’s Trust Partnership Assessment, a tool by which Children’s Trust measures their success at building capacities of partner organizations to provide services within the community. The Partnership Assessment examines whether specific capacities have been built and if not, what supports are needed to achieve those specific capacities. In this way, Children’s Trust demonstrates its impact as a partner with community-based organizations to build their capacities for successful and sustained service implementation. Learn more about Children’s Trust here.

ECOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES

In Chapter 1, the ecological model was described, and it involved multiple layers involving individuals, groups, organizations, communities, and the larger society. As is evident from the many case studies in this textbook, individuals can influence communities and communities can influence societies. In return, societies can influence communities and communities can influence individuals. This ecological model provides a useful framework to better understand the complex relationships among factors that contribute to social and community problems. Program developers and implementers need to be aware of this ecological model, as it provides a strong rationale to target our work toward multiple levels of influence. By considering ecological issues, we are better able to avoid and reduce biases (e.g., attribution effect, victim-blaming, racial prejudice) that can contribute to and perpetuate injustice. This can be particularly important for program implementers who support practitioners working in difficult and under-resourced settings. Case Study 18.4 applies the ecological model to the risk and protective factors involving child abuse and neglect.

Case Study 18.4

The Empower Action Model ®

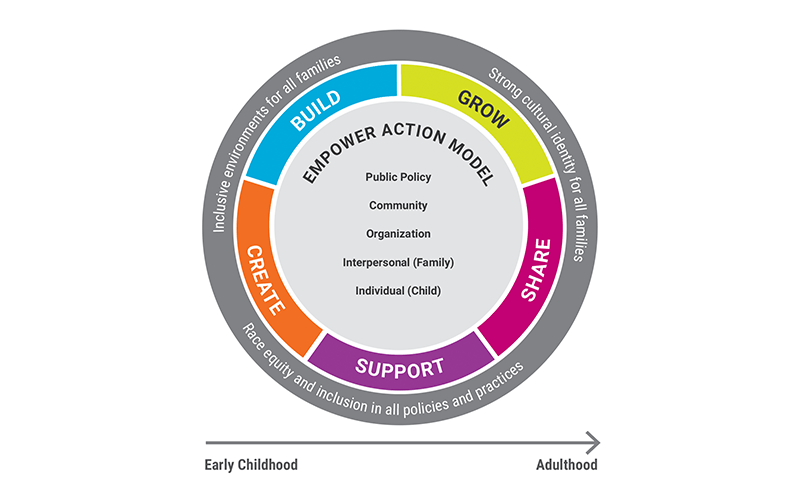

Children’s Trust, led by Melissa Strompolis, a Community Psychologist, and an interdisciplinary team of researchers, practitioners, and community members developed “The Empower Action Model™” as a blueprint for communities to prevent child abuse and neglect and build well-being and resilience.

The Empower Action Model™ uses an expanded version of the ecological model to ensure that levels of influence are identified and protective factors are promoted among children, families, organizations, communities, and public policies (Srivastav, Strompolis, Moseley, & Daniels, 2019a). For example, parents and caregivers can protect their children by focusing on child resilience. Organizations can emphasize policies and practices that promote employee health and well-being. Communities can build protective environments for children, including parks, schools, faith-based settings, social services, and health facilities. Policymakers can also prioritize programs and initiatives that support child health and well-being (Srivastav, Strompolis, Moseley, & Daniels, 2019b). Adapting the ecological model to the mission of Children’s Trust is helping communities all over South Carolina address the very challenging problem of abuse and neglect.

Figure 3 below is useful in addressing some of the specific implementation problems discussed in this chapter.

GIVING IT AWAY

We conclude this chapter with another barrier that confronts so many people: critical knowledge about the effectiveness of programs remains in privileged settings, such as among academic and scientific audiences, behind paywalls and professional dues. Just as researchers who use participatory methods value community-held knowledge, participatory methods increase the utility and ownership of research findings in communities. Participatory methods aim to support community partners who need to have ongoing access to information and resources.

Community psychologists work to share information to reduce the access imbalance between scientists and communities. As one example, this textbook is an open-access book designed to provide an accessible, free introduction to Community Psychology. Undergraduates can now freely join the Society for Community Research and Action as an Associate member, something that the editors of this textbook successfully advocated for with the leadership of this organization. The Community Psychologist and Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice are also online and open access. Throughout this book, consistent with community-centered values and capacity-building principles, you can learn about free and open blogs, podcasts, and webinars based on collaborations between community psychologists and communities, putting new research knowledge to greater use.

SUMMING UP

In this chapter, we have shown that the research conducted by psychologists does not often have an impact on the social and community problems that need our attention. One reason this information is not widely spread is that many programs, practices, and policies continue to be developed with minimal input from community members. More and more, we are recognizing the problems with this one-sided unidirectional transfer of knowledge.

But the field of Community Psychology does offer a solution to this problem, and by following its values, there is a higher likelihood that the research will be used by community members and those in a position of policy. This chapter has shown the advantages of using participatory research methods, which emphasize more equitable engagement in the creation and use of scientific knowledge. When using such methods, there is a higher chance that the research will actually translate into programs and be used by members of the community even when the researchers have finished their work. A key to this approach is building capacities for local communities to sustain and grow their efforts. Often problems that we face are complicated, and the field of Community Psychology offers an ecological approach to target multi-layered contributors to problems so that useful and effective approaches are widely implemented.

Critical Thought Questions

- Where have you seen a new policy or practice implemented that was not effective?

- What Community Psychology approaches would have helped in this situation?

- What are the advantages of partnering with those closest to community problems to improve implementation?

- In the case studies, what types of organizations are the community psychologists working in or partnering with to address implementation problems?

- After reading this chapter, which implementation problems do you believe are hardest to address?

Take the Chapter 18 Quiz

View the Chapter 18 Lecture Slides

____________________________________________________________________

REFERENCES

Anyon, Y., Roscoe, J., Bender, K., Kennedy, H., Dechants, J., Begun, S., & Gallager, C. (2019). Reconciling adaptation and fidelity: Implications for scaling up high quality youth programs. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 40, 35–49

Balas, E. A., & Boren, S. A. (2000). Managing clinical knowledge for health care improvement. Yearbook of Medical Informatics, 9, 65-70.

Brownson, R. C., Coldtiz, G. A., & Proctor, E. K. (2018). Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice (2nd edition). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Dalton, J., & Wolfe, S. M. (2012). Joint column: Education connection and the community practitioner. The Community Psychologist, 45, 7-13.

Institute of Medicine (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Retrieved from http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2001/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm-A-New-Health-System-for-the-21st-Century.aspx

Jason, L. A., Glantsman, O., O’Brien, J. F., & Ramian, K. N. (2019). Introduction to the field of Community Psychology. In L. A. Jason, O. Glantsman, J. F. O’Brien, & K. N. Ramian (Eds.), Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an agent of change. Retrieved from https://press.rebus.community/introductiontocommunitypsychology/chapter/intro-to-community-psychology/

Jason, L. A., Keys, C. B., Suarez-Balcazar, Y., Taylor, R. R., Davis, M., Durlak, J., & Isenberg, D. (Eds.). (2004). Participatory community research: Theories and methods in action. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Robertson E. B., Sims B. E., & Reider E. E. (2012). Partnerships in drug abuse prevention services research: Perspectives from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 39, 327–330.

Scaccia, J. P., Cook, B. S., Lamont, A., Wandersman, A., Castellow, J., Katz, J., & Beidas, R. S. (2015). A practical implementation science heuristic for organizational readiness: R = Mc2. Journal of Community Psychology, 43(4), 484–501. doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21698

Spoth, R., Rohrbach, L. A., Greenberg, M., Leaf, P., Brown, C. H., Fagan, A., … & Hawkins, J. D. (2013). Addressing core challenges for the next generation of type 2 translation research and systems: The translation science to population impact (TSci Impact) framework. Prevention Science, 14, 319–351.

Srivastav, A., Strompolis, M., Moseley, A., & Daniels, K. (2019a). The Empower Action Model©: Mobilizing prevention to promote well-being and resilience. Retrieved from https://scchildren.org/wp-content/up...arch-brief.pdf

Srivastav, A., Strompolis, M., Moseley, A., & Daniels, K. (2019b). The Empower Action Model©: A framework for promoting equity, health, and well-being. Health Promotion Practice.

Wandersman, A., & Florin, P. (2003). Community interventions and effective prevention. American Psychologist, 58, 441-448.

Wolfe, S. M. (2019). Practice competencies. In L. A. Jason, O. Glantsman, J. F. O’Brien, & K. N. Ramian (Eds.), Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an agent of change. Retrieved from https://press.rebus.community/introductiontocommunitypsychology/chapter/practice-competencies/

Zimmerman, L., Lounsbury, D. W., Rosen, C. S., Kimerling, R., Trafton, J. A., & Lindley, S. E. (2016). Participatory system dynamics modeling: Increasing stakeholder engagement and precision to improve implementation planning in systems. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 1–16.