9.19: William the Conqueror’s Rule

- Page ID

- 163856

Learning Objective

- Analyze the reasons behind the creation of the Domesday Book and why it is such an important historical document

Key Points

- After he launched the Norman conquest of England in 1066, William was crowned king and set about consolidating his power and authority.

- Several unsuccessful rebellions followed, but by 1075 William’s hold on England was mostly secure, allowing him to spend the majority of the rest of his reign on the continent.

- After the political upheaval of the Norman conquest, and the confiscation of lands that followed, William’s interest was to determine property holdings across the land and understand the financial resources of his kingdom, which was carried out in the Domesday Book.

- The aim of the Domesday Book was to determine what each landholder had in worth (land, livestock etc. ) to determine what taxes had been owed under Edward the Confessor.

- The Domesday Book is considered the oldest public record in England; no survey approaching the scope and extent of the Domesday Book was attempted again until 1873.

Terms

William the Conqueror

The first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 1087.

Edward the Confessor

One of the last Anglo-Saxon kings of England and usually regarded as the last king of the House of Wessex, ruling from 1042 to 1066.

William the Conqueror’s Rule

Although William’s main rivals were gone after the Battle of Hastings, he still faced rebellions over the following years and was not secure on his throne until after 1072. After further military efforts, William was crowned king on Christmas Day 1066 in London. He made arrangements for the governance of England in early 1067 before returning to Normandy. Several unsuccessful rebellions followed, but by 1075 William’s hold on England was mostly secure, allowing him to spend the majority of the rest of his reign on the continent. The lands of the resisting English elite were confiscated; some of the elite fled into exile.

To control his new kingdom, William gave lands to his followers and built castles commanding military strongpoints throughout the land. Other effects of the conquest included the introduction of Norman French as the language of the elites and changes in the composition of the upper classes, as William reclaimed territory to be held directly by the king and settled new Norman nobility on the land. More gradual changes affected the agricultural classes and village life; the main change appears to have been the formal elimination of slavery, which may or may not have been linked to the invasion. There was little alteration in the structure of government, as the new Norman administrators took over many of the forms of Anglo-Saxon government.

William did not try to integrate his various domains into one empire, but instead continued to administer each part separately. William took over an English government that was more complex than the Norman system. England was divided into shires or counties, which were further divided into either hundreds or wapentakes. To oversee his expanded domain, William was forced to travel even more than he had as duke. He crossed back and forth between the continent and England at least nineteen times between 1067 and his death.

William’s lands were divided after his death; Normandy went to his eldest son, Robert, and England to his second surviving son, William.

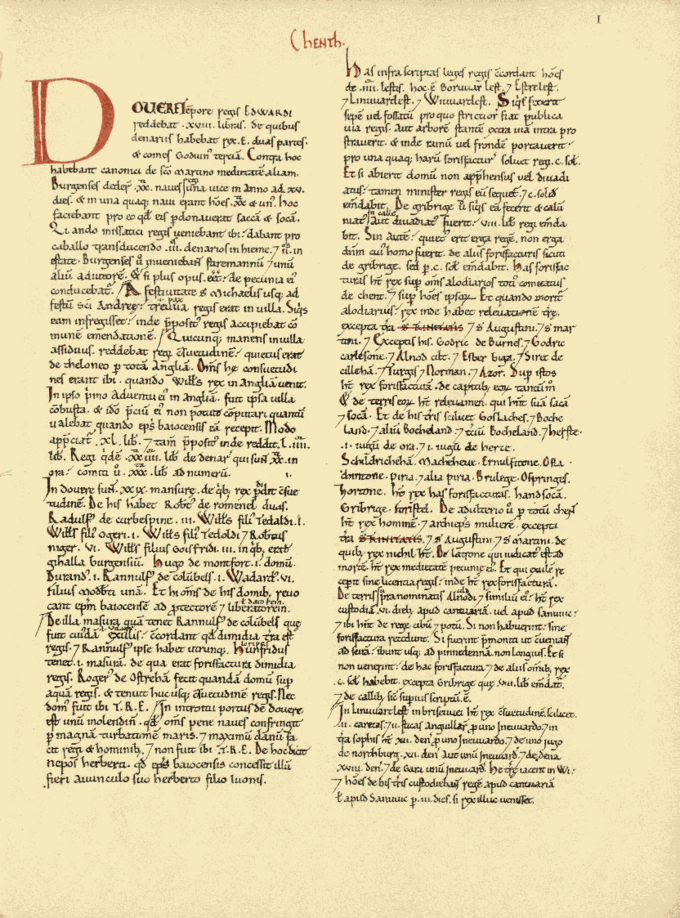

Domesday Book

The Domesday Book is a manuscript record of the great survey, completed in 1086 on orders of William the Conqueror, of much of England and parts of Wales. The aim of the great survey was to determine what or how much each landholder had in land and livestock, and how much it was worth. The survey’s ultimate purpose was to determine what taxes had been owed under Edward the Confessor.

The assessors’ reckoning of a man’s holdings and their value, as given in the book, was dispositive and without appeal, and thus the name Domesday Book came into use in the 12th century.

Purpose of the Domesday Book

After a great political convulsion like the Norman Conquest, and the wholesale confiscation of landed estates that followed, it was in William’s interest to make sure that the rights of the crown, which he claimed to have inherited, had not suffered in the process. In particular, his Norman followers were more likely to evade the liabilities of their English predecessors, and there was growing discontent at the Norman land-grab that had occurred in the years following the invasion. William required certainty and definitive reference points as to property holdings across the nation so that they might be used as evidence in disputes and purported authority for crown ownership.

The Domesday survey therefore recorded the names of the new landholders and the assessments on which their taxes were to be paid. But it did more than this; by the king’s instructions, it endeavored to make a national valuation list, estimating the annual value of all the land in the country at three points in time:

- At the time of Edward the Confessor’s death;

- When the new owners received it;

- At the time of the survey.

Further, it reckoned, by command, the potential value as well.It is evident that William desired to know the financial resources of his kingdom, and it is probable that he wished to compare them with the existing assessment. The great bulk of the Domesday Book is devoted to the somewhat arid details of the assessment and valuation of rural estates, which were as yet the only important sources of national wealth. After stating the assessment of a manor, the record sets forth the amount of arable land, and the number of plough teams (each reckoned at eight oxen) available for working it, with the additional number (if any) that might be employed; then the river-meadows, woodland, pasture, fisheries (i.e. fishing weirs), water-mills, salt-pans (if by the sea), and other subsidiary sources of revenue; then the number of peasants in their several classes; and finally a rough estimate of the annual value of the whole, past and present.

Importance

The importance of the Domesday Book for understanding the period in which it was written is difficult to overstate. It is considered the oldest public record in England and is probably the most remarkable statistical document in the history of Europe.

No survey approaching the scope and extent of the Domesday Book was attempted until the 1873 Return of Owners of Land (sometimes termed the Modern Domesday), which presented the first complete, post-Domesday picture of the distribution of landed property in the British Isles.

Sources

- Boundless World History. Authored by: Boundless. Located at: https://www.boundless.com/world-history/textbooks/boundless-world-history-textbook/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike