3.5: Social Change and Resistance

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 104048

- Erika Gutierrez, Janét Hund, Shaheen Johnson, Carlos Ramos, Lisette Rodriguez, & Joy Tsuhako

- Long Beach City College, Cerritos College, & Saddleback College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Current Immigration Issues and the Need for Social Change

With the rise of tougher immigration policies and xenophobic-driven hate crimes (as discussed in Section 3.4), immigrants in the United States have many obstacles to overcome. The next section will highlight some of the most pressing legal matters, as well as, human rights concerns that require social change through a social justice lens.

Immigration Policy and Legal Status Issues

DACA, AB 540, and the DREAM Act

There have been some contemporary changes to immigration matters around undocumented youth in the United States. While these changes are positive, they are temporary. Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) came about from an executive memorandum called, "Exercising Prosecutorial Discretion with Respect to Individuals Who Came to the United States as Children," on behalf of President Barack Obama in 2012 (United States Department of Homeland Security, 2012). DACA allows temporary protection to non-U. S. citizens from deportation, as well as, provide them with renewable work permits. The Anti-Defamatory League (ADL, 2020) writes,

DACA enables certain people who came to the U.S. as children and meet several key guidelines to request consideration for deferred action. It allows non-U.S. citizens who qualify to remain in the country for two years, subject to renewal. Recipients are eligible for work authorization and other benefits, and are shielded from deportation. The fee to request DACA is $495 every two years.

While DACA can be renewable, it is temporary and in 2017, the Trump administration attempted to end DACA, by rescinding it.

After the Trump administration ordered an end to DACA in 2017, several lawsuits were filed against the termination of DACA. Two federal appellate courts have now ruled against the administration, allowing previous DACA recipients to renew their deferred action, and the Supreme Court agreed to review the legal challenges" (ADL, 2020).

In June 2020, the Supreme Court issued a 5-4 decision finding that the Trump administration’s termination of DACA was "judicially reviewable" and "done in an arbitrary and capricious manner" (National Immigration Center, 2020; Supreme Court of the United States, 2020). For now, DACA seems to be safe, but DACA is not a permanent solution.

In 2001, California Assembly Bill (AB) 540 was signed into law by Governor Gray Davis and it would go into effect in 2002. According to the UCLA Center for Labor Research and Education (2008), "AB 540 is a California law that allows out-of-state students and undocumented students who meet certain requirements to be exempt from paying nonresident tuition at all public colleges and universities in California." While AB 540 makes college education more accessible and affordable for undocumented immigrants, it provides no pathway for amnesty and permanent legal residency and/or citizenship.

A more permanent solution for undocumented/non-U.S. citizen youth would be to finally pass the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act (DREAM Act). According to the ADL (n. d.), the DREAM Act "was a bill in Congress that would have granted legal status to certain undocumented immigrants who were brought to the United States as children and went to school here." Though introduced in Congress in 2001, it has never passed. The minors that would have benefited from this act are referred to as, DREAMers. Given the stalemate regarding this immigration legislature and the unclear trajectory of DREAMers, President Obama promoted the DACA program. Regarding DACA, President Obama remarked,

Precisely because this is temporary, Congress needs to act. There is still time for Congress to pass the DREAM Act this year, because these kids deserve to plan their lives in more than two-year increments. And we still need to pass comprehensive immigration reform that addresses our 21st century economic and security needs (Office of the Press Secretary, 2012).

In the interest of social justice and positive social change, the passage the DREAM Act would be a more solid step toward immigration reform. For more information regarding DACA and the DREAM Act, please review the Fact Sheet by the American Immigration Council.

Executive Order 13769 - "Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States"

Executive Order 13769 was signed by President Donald Trump in 2017 and it is most commonly referred to as the "Muslim Ban." This act attempted to ban immigrants from seven predominantly Muslim nations, which are Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen (white House, 2017). This ban has been challenged legally several times and was overturned in the courts but a revised policy was tentatively permitted by the Supreme Court. According to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU, 2020),

in a 5-4 ruling, the Supreme Court upheld the Trump administration’s third Muslim ban. As disappointing as this decision is, it does not affect the ACLU of Washington’s case against the Trump Administration’s refugee ban, Doe et al. v. Trump.

The third Muslim Ban, otherwise known as Muslim Ban 3.0, was upheld by the Supreme Court in 2018 and it is currently in effect, but with some exceptions regarding refugee cases (ACLU, 2020). Muslim Ban 3.0 impacts immigrants from the following countries: Iran, Libya, North Korea, Somalia, Syria, Venezuela, and Yemen. The Muslim Bans reflect extreme xenophobia (fear of strangers and/or foreigners) and Islamophobia (prejudice and/or discrimination against Muslims and the Islamic religion).

Reunification

The United States policy prioritizes family reunification, and immigrant and refugees’ spouses and children are eligible to immigrate without visa quotas. The majority of current immigrants are family members being reunited with United States citizens or permanent residents and all are processed through the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS).

In addition to these policies that promote family reunification, there are now more accepting policies to support reunification of gay citizens and their immigrant spouses. Historically, United States immigration policy has denied immigration to same-sex orientation applicants. Under the 1917 Immigration Act, homosexuality was grounds for exclusion from immigration. In 1965, Congress argued that gay immigrants were included in a ban on “sexual deviation” (Dunton, 2012). The ban against gay immigrants continued until 1990, when the Immigration and National Act was amended, removing the homosexual exclusion. Moreover, asylum has been granted for persecution due to sexual orientation (Dunton, 2012). Until 2013, immigrants and refugees could apply for residency or visas for their opposite-sex spouses. There was no provision made for same-sex partners. Following the overturn of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), citizens and permanent residents can now sponsor their same-sex spouses for visas. United States citizens can also sponsor a same-sex fiancé for a visa (USCIS, 2014).

Despite these advances, there are two large challenges faced by immigrants seeking reunification. First, it requires substantial time and resources, including legal counsel, to navigate the visa system. Adults can petition for permanent resident visas for themselves and their minor children, but processing such applications can take years. Currently, children of permanent residents can face seven-year wait times to be accepted as legal immigrants (Meissner, Meyers, Papademetriou & Fix, 2006).

In some cases, children can age out of eligibility by the time the application is processed and the visa is granted. Such children then go to the end of the waiting list for adult visa processing (Brown, 2014). The 2002 Child Status Protection Act is designed to protect children against aging out of visa eligibility when the child is the primary applicant for a visa, but the act does not state if it applies if a parent was applying on behalf of their family (Brown, 2014). In the 2014 ruling to Cuellar de Osorio v. Mayorkas, the Supreme Court found that the child status protection act does not apply for children when a parent is applying on behalf of their family. Such young adults have already generally been separated from family for many years, and will now be separated for years or decades more.

Undocumented Families

For families who do not have a sponsoring family member, have a sponsoring employer, or originate from a country with few immigrants, the options for legal immigration to the United States are very limited. Those families who choose to travel to the United States face substantial barriers, including a perilous trip across the border, few resources, and constant threat of deportation.

One of the most dangerous times for undocumented families is the risky trip across the border. In order to avoid border patrol, undocumented immigrants take very dangerous routes across the United States border. The vast majority of all apprehensions of undocumented immigrants are on the border (while the remainder is apprehended through interior enforcement). For example, in 2014 ICE conducted 315,943 removals, 67% of which were apprehended at the border (nearly always by the Border Patrol), and 33% of which were apprehended in the interior (ICE, 2014). The trip and efforts to avoid Border Patrol can be physically dangerous and in some cases, deadly. The acronym ICE symbolizes the fear that immigrants feel about capture and deportation. A deportee in Exile Nation: The Plastic People (2014), a documentary that follows United States deportees in Tijuana, Mexico, stated that ICE was chosen as the acronym for the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency because it “freezes the blood of the most vulnerable.”

Even after arrival at the interior of the United States, undocumented immigrants feel stress and anxiety relating to the fear of deportation by ICE (Chavez, Lopez, Englebrecht, & Viramontez Anguiano, 2012). This impacts their daily life activities. Undocumented parents sometimes fear interacting with school, health care systems, and police, for fear of revealing their own undocumented status (Chavez et al., 2012; Menjivar, 2012). They may also avoid driving, as they are not eligible for a driver’s license.

Since 2014, the United States Department of Homeland Security (USDHS) has placed a new emphasis on deporting undocumented immigrants. Department efforts generally prioritize apprehending convicted criminals and threats to public safety, but recent operations have taken a broader approach. In the opening weeks of 2016, ICE coordinated a nationwide operation to apprehend and deport undocumented adults who entered the country with their children, taking 121 people into custody in a single weekend. The majority of these individuals were families who applied for asylum, but whose cases were denied. Similar enforcement operations are planned (DHS Press Office, 2016). In many cases, the parents’ largest concern is that immigration enforcement will break up the family. Over 5,000 children have been turned over to the foster care system when parents were deported or detained. This can occur in three ways:

- when parents are taken into custody by ICE, the child welfare system can reassign custody rights for the child,

- when a parent is accused of child abuse or neglect and there are simultaneous custody and deportation proceedings, and

- when a parent who already has a case open in a child welfare system is detained or deported (Enriquez, 2015; Rogerson, 2012).

In the words of a Mexican Immigrant describing how his fear of deportation grew after his baby daughter was born,

one of my greatest fears right now is for anybody to take me away from my baby, and that I cannot provide for my baby. Growing up as a child without a father [as I did], it’s very painful… I felt like there was no male to protect them (Enriquez, 2015).

Although the perilous trip and threat of deportation are significant challenges for undocumented immigrant families, there are two recent policy changes that offer new opportunities and protections for undocumented families. First, some states have sought to expand the educational supports available to undocumented immigrants. The State of Minnesota, for example, enacted the “Dream Act” into law in 2013. This unique act, which is also known as the “Path to Prosperity Act,” makes undocumented students eligible for State financial aid (Brunswick, 2013).

Second, there are now greater protections for unaccompanied children. In some cases, children travel across the border alone, without their families. They may be traveling to join parents already in the United States, or their parents may send them ahead to try to obtain greater opportunities for them. As a result of human rights activism, unaccompanied and separated immigrant children are now placed in a child welfare framework by licensed facilities under the care of the Office of Refugee Replacement (ORR)(Somers, 2011). They provide for education, health care, and psychological support until they can be released to family or a community (Somers, 2011). Each year, 8,000 unaccompanied immigrant children receive care from the ORR (Somers, 2011).

Immigration Policy as Social Change

There are three shifts in immigration policy that are critical for the well-being of families. First, policy should shift to accelerate family reunification for those families whose visas have been accepted. Families are currently separated from their children for years, caught in a holding pattern of waiting. This leads to stress, grief, and difficulty building relationships during key developmental times in a child’s life. Accelerating processing applications and shorter wait times would facilitate greater family well-being.

Second, policy could provide greater protection for vulnerable children in undocumented or mixed-status families. In cases where a parent is deported, the child’s welfare should be carefully considered in whether to leave the child in the care of a local caregiver or provide the option to send the child to the home country with their parent.

Third, policies that are either directly and/or indirectly discriminate against a particular ethnic/racial/religious group, like the Muslim Ban, should be immediately rescinded. The jarring racism invoked by these kinds of policies justified as "national safety" is antithetical to a true democracy.

Human Rights Issues

While human rights have in large part been internationalized, they have to be implemented at the domestic level. According to Donnelly (2003), this dichotomy permits countries to fulfill dual and seemingly incompatible roles: essential protector and principle violator. In the United States, this duality can be seen in the difference between the laws upon which the country was founded and the implementation of these laws in an equitable fashion.

The Bill of Rights, as codified in the United States Constitution, lays out specific human rights that parallel those to which the majority of international human rights regimes adhere. Thus, the founding myths of this country are grounded in the central place of human rights (Donnelly, 2003). In fact, many if not most liberal democracies share these constitutive principles. As Koopmans (2012) points out, “internal constitutive principles – such as the right to exercise one’s religion…imply that the granting of rights to individuals and groups will be more similar across democracies than it will be between them and non-democracies." And yet, there remain significant areas where United States domestic policy can be seen to violate various rights of various portions of the population at any given time.

Political Issues

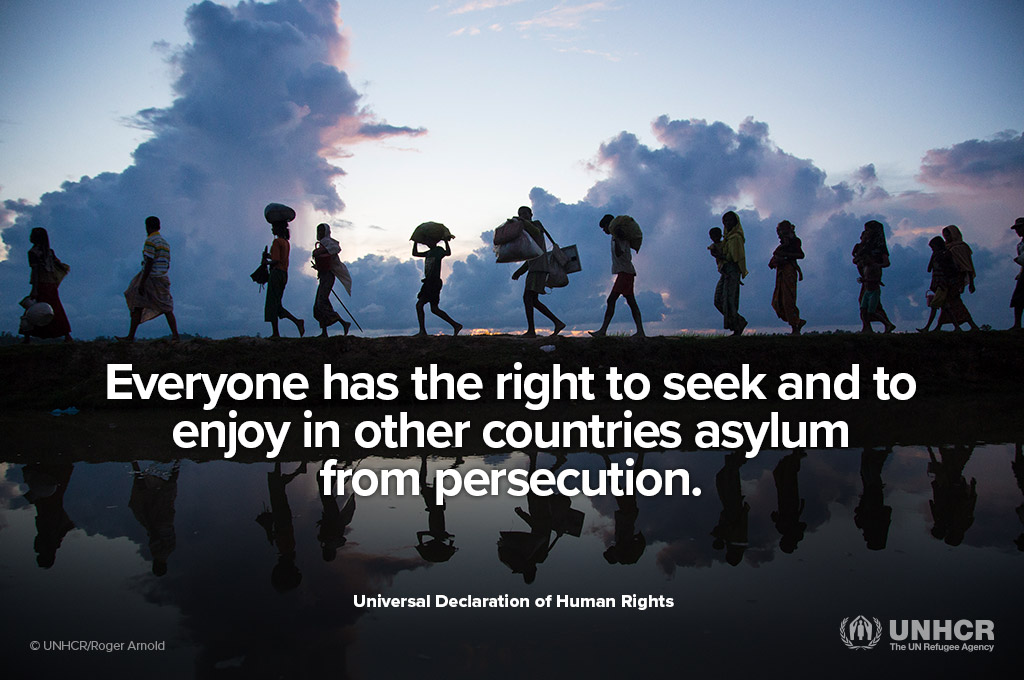

The most pressing human rights issues in the United States revolve around immigrant and refugee families. The strategic priorities outlined by the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCR) include: (a) countering discrimination; (b) combating impunity and strengthening accountability; (c) pursing economic, social and cultural rights and combating poverty; (d) protecting human rights in the context of migration; (e) protecting human rights during armed conflict, violence and insecurity; and (f) strengthening international human rights mechanisms and the progressive development of international human rights law. Priorities (a), (c) and (d) make up the elements most germane to the human rights situation in the United States today. The difficulties faced by immigrant and refugee families include classism, racism, sexism, and discrimination on the basis of religion as well as uncertain economic circumstances.

The United States voted in favor of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR, 1948) but it did not ratify (i.e., sign) the document. While various theories attempt to explain relevant reasons, numerous rights enshrined in the UDHR are in the Constitution and Bill of Rights (Advocates for Human Rights, n.d.) The United States’ apparent sense of exceptionalism to international standards and norms has been evidenced over time in two main ways: the ongoing torture of Guantanamo Bay detainees and the revelation that American social scientists were involved in reverse engineering torture techniques for the government. While the United States may at times act outside of the limitations established by the international community (and specifically the UDHR) this stance is not the focus of this chapter. As the UNCHR notes, “national and local politicians have sought to mobilize electoral support by promoting xenophobic sentiments, exaggerating the negative impact of hosting refugees while ignoring the fact that refugees can actually attract international assistance and investment to an area, creating new jobs and trading opportunities” (2006). In this way the refugee situation has often been used as a political football in United States political culture.

Legal Issues

The current legal climate in the United States is negatively skewed against international human rights, particularly as it pertains to the legal status of displaced persons (persons who are forced to leave their home country due to war, persecution or natural disasters). There are many reasons to be pessimistic about successfully using international human rights arguments as a way of advancing displaced person’s rights in the United States (Chilton, 2014; Cole, 2006; International Council on Human Rights, 2008). According to Cole (2006), in spite of its history as a nation of immigrants, the United States remains deeply nationalist and quite parochial; the law reflects that parochialism. Furthermore, “International human rights arguments are often seen as the advocates’ last refuge pulled out only when there is no other authority to cite" (Cole, 2006).

However, this trend seems to be moving the national towards the transnational in terms of how human rights law is perceived and implemented in the legal system and culture of the United States. This means that increased globalization and interdependence has had the effect of strengthening the influence of international human rights standards in the United States. The hope is that these standards may “command greater respect from our own domestic institutions" (Cole, 2006). Cole further posits that the paradigm shift in the United States from national to transnational, merging the national and the international, parallels the shift in the United States from state to federal power that occurred with the advent of the New Deal in the 1930s. In other words, there is reason to hope that gradual change is coming within the legal system in the United States with regards to its acceptance of the international human rights regimes norms and standards.

Refugee families and asylum seekers

The terms of refugee and asylum seeker are often used interchangeably, but there are important legal differences between them, as discussed in Chapter 3.1. These differences not only determine which resources they are eligible for once arriving in the United States, but also in which phase of the legal process they are currently.

Refugees

An estimated 51.2 million people were displaced since 2013 as a direct result of persecution, war, violence, and human rights atrocities (UNHCR, 2013). In 2013, the United States Department of Justice (USDOJ, 2014) received 36,674 asylum applications but only approved 9,993. The remaining applications were abandoned (1,439), withdrawn (6,400), or simply unaccounted for (11,391). Being that the recent United States population estimate is 318 million people, refugees make up less than 1% of the population. The families seeking asylum from their home countries often have significant traumatic histories and thus can loom larger in the public sphere than other types of immigrants. Most of these families are fleeing extreme injustices in their home country, such as war, political instability, genocide and severe oppression. Because of the uncertainty of their original situation, it remains quite difficult for the USDHS to determine who is legitimately eligible for asylum.

Asylum seekers

A further complication for government agencies lies in trying to determine when and how to return rejected asylum seekers to their home countries (Koser, 2007). Within the domain of international migration studies there has been traditionally a differentiation made between refugees (involuntary migration) and labor seekers (voluntary migration). While the former group represents the political outcome of global systems and interactions and the latter group represents the economic outcome, nonetheless, it is quite clear that people migrate for a whole complex series of reasons, including social ones (Koser, 2007). If an asylum-seeker’s claim for asylum is denied, they are placed in deportation proceedings. During this process, an immigration judge (IJ) works with the asylum-seekers’ attorney to determine the removal process. It is important to note that displaced persons are rarely detained and/or immediately placed on the next flight to their country of origin.

Sex Trafficking and Human Trafficking

The United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress, and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, defines trafficking as the “…recruitment, transfer, harboring or receipt of persons, by any means of threat or force…for the purpose of exploitation.” This crime is globally categorized as either sex trafficking or labor trafficking. According to the DOJ (2006), there have been an estimated 100,000 to 150,000 sex trafficking victims in the United States since 2001. Furthermore, estimates of persons currently in situations of forced labor or sexual servitude in the United States range from 40,000 to 50,000.

The leading countries of origin for foreign victims in fiscal year (FY) 2011 were Mexico, Philippines, Thailand, Guatemala, Honduras, and India (United States Department of State, 2012). In 2011, “notable prosecutions included those of sex and labor traffickers who used threats of deportation, violence, and sexual abuse to compel young, undocumented Central American women and girls into hostess jobs and forced prostitution in bars and nightclubs on Long Island, New York” (United States Department of State, 2012). According to the International Labor Organization (ILO, 2016), globally an estimated 4.5 million women, men, and children are sexually exploited. There is some legal benefit (a self-petitioned visa in the United States) in place for those who cooperate in prosecuting their traffickers, as these visa victims can receive four years of legal status. Unfortunately, far fewer receive immigration aid than are identified as victims of sex trafficking (United States Department of State, 2012).

Human trafficking is another area where issues of physical safety and sexual exploitation of immigrant and refugee women and children come to the forefront as a human rights issue. Contrary to popular thought, sex trafficking is an ongoing and insidious activity that also includes young boys, and the prevalence of human and sex trafficking in the United States disproportionately affects the more vulnerable, under-resourced populations such as immigrant and refugee families (United States Department of State, 2012).

Mixed Status (Deportation) and Separation of Families

One of the most pressing human rights issues for displaced persons in the United States today is the mixed-status families (i.e., documented and undocumented). These are families whose members hold different levels of legal status in the country. Some members of the family may be documented persons (such as asylum-seeker, permanent resident or citizen) while others have undocumented status. Though the children born to undocumented migrants typically receive citizenship by birth, this does not change their parents’ legal status. The exception, however, is when undocumented parents return to their country of origin and wait until that child is 18 years of age; at that point the young adult child can sponsor them in becoming United States citizens. When families consist of members whose legal status is documented as well as undocumented, this uncertain distal context can set the stage for significant vulnerabilities within the family.

Brabeck and Xu (2010), who studied of the effects of detention and deportation on children of Latino/a immigrants, found that the legal vulnerability of Latino/a parents, as measured by immigration status and detention and deportation experience, predicted child well-being. In other words, the children suffer when they cannot be sure whether their parents will be able to stay and live with them in United States on a day-to-day basis. Kanstroom (2010) writes that

although international law recognizes the power of the state to deport noncitizens, international human rights law has also long recognized the importance of procedural regularity, family unity, and proportionality. When such norms are violated the State may well be obligated to provide a remedy.

Once again the paradox of international human rights norms conflicts with the actual social and political practices of the United States; as of this writing the issue remains a political football in the United States.

The most egregious contemporary example of the separation of families are the children deliberately taken away from their families and put in cages. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), children who were already-traumatized were then caged within locked warehouses, left to sleep under blankets akin to aluminum foil (Vinson, 2020). This separation and harsh treatment is linked to the Trump Administration's "zero tolerance policy" in which

U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions ordered prosecutors along the border to 'adopt immediately a zero-tolerance policy' for illegal border crossings. That included prosecuting parents traveling with their children as well as people who subsequently attempted to request asylum (Domonoske & Gonzales, 2018).

Amidst great pushback and critique of the "zero-tolerance policy," President Trump signed Executive Order 13841, Affording Congress an Opportunity to Address Family Separation, on June 20, 2018 (white House, 2018). Unfortunately, the SPLC reports that six days after Executive Order 13841 was signed,

U.S. District Judge Dana Sabraw issued a nationwide injunction to halt family separations. But since then, the practice has continued under the American public’s nose (Vinson, 2020).

The result of these deliberate separations was not just the traumatization of migrant children, but the inability by the federally appointed lawyers "track down the parents of 545 children and that about two-thirds of those parents were deported to Central America without their children, according to a filing Tuesday from the American Civil Liberties Union" (Ainsley & Soboroff, 2020). However, the cruelty does not end there. There is a recent report that alleges that unaccompanied migrant children are treated poorly and inhumanely by the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) staff (Armus, 2020). While those complaints are being investigated, there have been at least seven children that have died while in immigration custody (Acevedo, 2019). Thus, the report that migrant children are being mistreated seems to be accurate given these multiple deaths. Upholding immigration policies and laws should not violate human rights nor result in the abuse and/or death of migrants while in detention.

Detention Without Trial and Other Detention Issues

In 2011, United States Congress passed the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) that codified, for the first time since the McCarthy era, indefinite detention without charge or trial. Subjecting refugees to detention induces unnecessary psychological fear and harm. Furthermore, it does not uphold the fundamental human rights principles set out in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) preamble (Prasow, 2012). The notion that people, whether citizens, documented or undocumented immigrants, could be held by the government indefinitely without access to the protections enshrined in the United States Constitution is a clear violation of international human rights law and anathema to human rights and civil liberties groups. As of late 2012, members of Congress proposed to have it repealed or amended. As noted by Senator Dianne Feinstein of California,

Just think of it. If someone is of the wrong race and they are in a place where there is a terrorist attack, they could be picked up, they could be held without charge or trial for month after month, year after year. That is wrong (Prasow, 2012).

The amendment that Senator Feinstein proposed, however, would protect only citizens and lawful residents; undocumented immigrants would still be subject to this odious practice.

Yet another odious practice associated with detention is the forced sterilization, by way of hysterectomies, of migrant women. As The Intercept reports, "At least 17 women treated by a doctor alleged to have performed unnecessary or overly aggressive gynecological procedures without proper informed consent remain in detention at Irwin County Detention Center, a privately run facility in Georgia housing U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement detainees" (Washington & Olivares, 2020). While this compulsory sterilization issue is focused around one facility and one doctor, it remains to be addressed if other facilities and/or doctors have also been involved. As these allegations are reviewed and investigated, some of the migrant women that have spoken out about these unnecessary and overly aggressive gynecological procedures have been deported while others are set to be deported (Washington & Olivares, 2020).

Past and Present Resistance

Immigrants face significant and complex challenges in achieving economic well-being. Legislation such as the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) and 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) currently limit immigrants’ access to employment, housing, and health services. The implementation of these restrictive policies is often fueled by misconceptions of the economic impact of immigrants in the greater society, especially the perception that undocumented immigrants place an economic burden on our health care system. Federal policies that facilitate more effective access to employment, housing, and healthcare and financial services are needed. Since federal policies are currently not effective and, given other general obstacles that immigrants face, immigrants and their allies continue to resist and demonstrate their resiliency as outlined below.

Labor Organizations

Some of the first organizations to advocate for and organize immigrants were labor unions. Two notable examples are the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing, and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA) and the United Farm Workers of America (UFW). Given the nature of the type of work that is represented by both unions, these unions were comprised of workers of many different characteristics including, but not limited to: immigrants, Latinos, Asian and Pacific Islanders, African Americans, men, and women.

UCAPAWA was formed in 1937 and unlike other unions at the time, this union embraced women in leadership roles. Moreover, this union demonstrated an intersectional approach to rights since labor, gender, and immigrant rights were so interconnected with one another. This intersectionality is best exemplified by Luisa Moreno, a Guatemalan immigrant that was the first Latina to serve on the executive committee of UCAPAWA (Acuña, 2015). Unfortunately, Luisa Moreno's efforts and activism were cut short as is stated here:

Moreno’s commitment to immigrant laborers endured across World War II. But in the postbellum 'red scare' that marked the onset of America’s Cold War with the Soviet Union, Moreno’s workers’ rights campaign was tragically truncated. Increasingly unsympathetic toward activist immigrants, the federal government in 1950 concocted a warrant for Moreno’s immediate deportation, citing her association with the Communist Party as a threat to national security. Rather than subject herself to the humiliation of forced removal, Moreno left the U.S. that November (Smith, 2018).

The tactic of threatening to deport labor and/or political activists is not uncommon, but it clearly is meant to undermine the efforts by immigrants attempting to help others and resist exploitative practices (Acuña, 2015).

The UFW represents the 1962 merger of two labor organizations Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) and National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), but it became an actual labor union in 1965 under the name, UFW (Acuña, 2015). Agricultural work has and continues to rely on immigrant laborers, however, the UFW historically had an adverse policy around undocumented immigrant workers. According to Frank Bardacke (2013),

These first members of the UFW felt threatened by the open border and by the large number of green carders and illegals who lived in Mexicali and were beginning to work in the table grapes...Becoming part of the official labor movement did nothing to ease [Cesar] Chavez’s fear that this new wave of illegal immigration would cripple his attempts to build his union, as the labor movement had a long history, especially in California, of opposing high wages for domestic union workers. The UFW’s anti-illegals policies fit smoothly within what has been, until very recently, a standard organizing approach of much of US labor.

Eventually, the anti-undocumented immigrant policies promoted within the UFW were terminated and in an effort to combat this xenophobic reputation, "they led the fight against Proposition 187, took the lead in other pro-immigrant campaigns, and have been strong advocates for the undocumented ever since (Bardacke, 2013)." It is interesting to see how unions have had to navigate the concerns of the workers they represent, which includes legal immigrants, but in doing so, may have ostracized undocumented immigrants. However, that no longer seems to be the case for the UFW or the newer unions and labor organizations that have been formed. Ruth Milkman's book (2000) discusses how more contemporary labor organizing is inclusive of undocumented immigrants when describing the Justice for Janitors Campaign and the more recent strategies employed by both the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees (HERE) and Service Employees International Union (SEIU).

California Proposition 187 and Arizona SB 1070

Unlike DACA and the proposed DREAM Act, not all contemporary immigration policies and legislation have been positive. To illustrate this point, California's Proposition 187 and Arizona's Senate Bill 1070 are among the most notorious examples of anti-immigrant discrimination. Regarding Proposition 187, Acuña (2015) writes,

the draconian SOS (Save Our State) Initiative, Proposition 187, appeared on the November 1994 California ballot. It proposed denying health and educational services to undocumented immigrants.

This proposition was approved by voters and was intended to go into effect, but was challenged legally. According to the ACLU (1999),

A court-approved mediation today ended years of legal and political debate over Proposition 187...The agreement confirms that no child in the state of California will be deprived of an education or stripped of health care due to their place of birth. It also makes clear that the state cannot regulate immigration law, a function that the U.S. Constitution clearly assigns to the federal government.

The extreme nativism of Proposition 187 galvanized immigrant's rights groups and allies whom took to the streets to protest. The Los Angeles Times (1994) reported that "In one of the largest mass protests in the city’s history, an estimated 70,000 demonstrators marched from the Eastside to Downtown on Sunday in boisterous condemnation of Proposition 187, the anti-illegal immigration initiative, and its best-known advocate, Gov. Pete Wilson" (McDonnell & Lopez, 1994). The large protests against Prop. 187 are a poignant example of resistance by immigrants and their allies and for immigrant's rights and immigration reform.

Comparably, Arizona SB 1070 was signed into law in 2010 by Governor Jan Brewer and it

aimed at preventing illegal immigration that has significantly affected the Mexico-bordering state over many decades. The law, entitled Support Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act, would require law enforcement officials to enforce existing federal immigration laws in the state by checking the immigration status of a person they have 'reasonable suspicion' of being in the U.S. illegally (FindLaw, 2018).

Like Prop. 187, this law was also legally challenged and was considered to be one of the strictest anti-immigrant laws in the U. S. (Archibold, 2010). Despite the years of legal battles, "the heart of SB1070 still beats, however faintly, after critics failed to strike down the requirement that law enforcers ask about people’s legal status during routine stops" (del Puerto, 2016). As reported in the Tucson Sentinel,

tens of thousands of protesters marched on Arizona's State Capitol in Phoenix Saturday as they demonstrated against the state's controversial immigration law, SB 1070...Police declined to estimate the size of the crowd, but it appeared at least 10,000 to 20,000 protesters braved temperatures that were forecast to reach 95 degrees by mid-afternoon. Organizers had said they expected the demonstration to bring as many as 50,000 people (Smith, 2010).

Ongoing protests and resistance to SB1070 continue given that it "gave birth to a spirit of activism among young immigrants" and "a decade after SB 1070 became law, local police agencies are enforcing it in different ways" (Arizona Central, 2020).

May Day Protests

In the previous section, large-scale protests that opposed anti-immigrant legislation were discussed. Perhaps the biggest protest organized to support immigration reform and immigrant rights was the May Day March of 2006, also referred to as "A Day Without Immigrants." As reported by The Guardian,

A sea of white-shirted protesters 300,000 strong, chanting "Si, se puede" ('Yes, it can be done') surged through Los Angeles. In Chicago police said up to 400,000 protesters had taken part in a rally. Other large demonstrations took place in Denver, which saw 75,000 protesters, Houston and San Diego (Glaister & MacAskill, 2006).

The 2006 May Day protests were not just massive, but took place throughout the United States over concerns over HR 4437 that would criminalize undocumented immigrants, in the name of toughen border control. Crucially, it does not offer any path to citizenship for those already residing in the US (Glaister & MacAskill, 2006). Since comprehensive immigration reform that would include amnesty for undocumented immigrant has not been achieved, another May Day protest was organized.

The second May Day March took place in 2017, but these protests happened all over the world. As reported by Elliot C. McLaughlin (2017) for CNN, "May Day protests turned violent in several cities around the world Monday as 'anarchists' forced police to cancel permits and arrest dozens of protesters in a day meant to celebrate workers and the gains made by labor advocates." The global spread of these protests highlights the need to address immigrant rights as both a national and transnational issue. Although there was violence at some of these rallies, this violence should not be used to distract from the focus on equitable immigration reform and the growing resistance against anti-immigration policies and rhetoric.

Immigrant Rights Movement and Activism

Thus far, multiple examples of organizing and activism by and for immigrants have been discussed, and they would all be considered to be in support of the Immigrant Rights Movement. (See more discussion of the Immigrant Rights Movement in Chapter 11.2). Paul Engler (2009) from the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict (ICNC) describes the Immigrant Rights Movement as "a vibrant social movement in the United States...emerged to protect these immigrants from discrimination and from many cases of excessively repressive enforcement of immigration laws, as well as to advocate for legislation that will provide a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants." Given the current and dramatic increase of nativism and xenophobia, the Immigrants Rights Movement has had an uptick in organizing efforts and activism. Here are a few examples:

- #NoKidsinCages is a campaign promoted by The Refugee AND Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services (RAICES) to support migrant justice and specifically bring attention to the the migrant children that have been separated from their families while still in immigration detention. People can become active by organizing, volunteering, donating, and even getting the word out via social media.

- Families Belong Together is a campaign "of the National Domestic Workers Alliance formed in response to the 2018 family separation crisis. Families Belong Together works with nearly 250 organizations representing Americans from all backgrounds who have joined together to fight family separation and promote dignity, unity and compassion for all children and families." Like the #NoKidsinCages campaign, folks can become active by volunteering, using social media to get the word out, and signing letters/petitions demanding the shut down of detention facilities and even the resignation of DHS officials.

- DREAMers the continued battle to finally get the DREAM Act passed has evolved and led to DREAMer activists that are "undocumented and unafraid." Most undocumented youth used to be scared to reveal their status for fear of reprisal, but more DREAMers are now outspoken about their situation and the need for immigration reform (Sabate, 2012). As described by Julissa Treviño (2018),

Beyond pushing for the DREAM Act, activists believe changes in the nation’s public discourse present an opportunity to expand the conversation. The face of DACA – and the immigration movement overall – has been high-achieving young immigrants whose accomplishments made them sympathetic to the general public.

While there is no one organization that represents all DREAMers and their allies, United We Dream is the largest immigrant youth-led organization. Similar to the two campaigns listed above, people can become active by signing petitions, starting campaigns, donating to organizations that focus around immigrant rights, and getting the word out through social media.

Future Directions

Research is needed to more deeply understand the values, needs, and stressors in immigrant and refugee families as they transition to new environments. Worry about supporting their families creates stress which can lead to mental health issues. We need to understand the connections between financial worry, labor stability, educational access, and mental health in these families - and find ways to support them. Moreover, we must assess the extent of the impact of contemporary xenophobic and nativistic policies on migrant families and finally provide comprehensive immigration reform that has been desperately needed since 1986 IRCA's amnesty provision.

Contributors and Attributions

- Gutierrez, Erika. (Santiago Canyon College)

- Ramos, Carlos. (Long Beach City College)

- Immigrant and Refugee Families (Ballard, Wieling, and Solheim) (CC BY-NC 4.0)

Works Cited

- Acevedo, N. (2019). Why are migrant children dying in U.S. custody? NBC News.

- Acuña, R.F. (2015). Occupied America: A History of Chicanos. 8th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Advocates for Human Rights. (n.d.). Human Rights and the U.S. The Advocates of Human Rights.

- Ainsley, J. & Soboroff, J. (2020). Lawyers say they can't find the parents of 545 migrant children separated by trump administration. NBC News.

- American Civil Liberties Union. (1999). CA'S Anti-Immigrant Proposition 187 is Voided, Ending State's Five-Year Battle with ACLU, Rights Groups. ACLU.org.

- American Civil Liberties Union. (2020). Timeline of the Muslim Ban. ACLU.org.

- Anti-Defamation League. (2020). What is DACA and who are the DREAMers? ADL.org.

- Anti-Defamation League. (n. d.). What is the Dream Act and Who are the Dreamers? ADL.org.

- Archibold, R.C. (2010). Arizona enacts stringent law on immigration. The New York Times.

- Arizona Central. (2020). SB 1070: A legacy of fear, divisiveness and fulfillment.

- Armus, T. (2020). Unaccompanied migrant children suffer ‘inhumane and cruel experience’ in cbp custody, report alleges. The Washington Post.

- Bardacke, F. (2013). The ufw and the undocumented. International Labor and Working-Class History 83, 162-169.

- Brabeck, K. & Xu, Q. (2010). The impact of detention and deportation on Latino immigrant children and families: a quantitative exploration. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 32(3), 341-361.

- Brown, K.J. (2014). The long journey home: Cuellar de Osario v. Mayorkas and the importance of meaningful judicial review in protecting immigrant rights. Boston College Journal Of Law & Social Justice 34(4), 1-13.

- Brunswick, M. (2013). Minnesota senate boosts undocumented students' college dreams. Star Tribune.

- Callahan, M. (2018). #Metoo, #Blacklivesmatter, #nobannowall: social movements likely to dominate 2018. News@Northeastern.

- Chavez, J.M., Lopez, A., Englebrecht, C.M., & Viramontez Anguiano, R.P. (2012). Sufren los niños: exploring the impact of unauthorized immigration status on children’s well-being. Family Court Review 50(4), 638-649.

- Chilton, A.S. (2014). Influence of international human rights agreements on public opinion. The Chicago Journal of International Law 15:1, 110-137.

- Cole, D. (2006). The idea of humanity: human rights and immigrants’ rights. Columbia Human Rights Law Review 37(3), 627-658.

- del Puerto, L. (2016). A Timeline – the tumultuous legal life of Arizona’s sb1070. The Arizona Capitol Times.

- Domonoske, C. & Gonzales, R. (2018). What we know: Family separation and 'zero tolerance' at the border. NPR.

- Donnelly, J. (2003). Universal Human Rights in Theory and Practice. 2nd ed. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Dunton, E.S. (2012). Same sex, different rights: amending U.S. immigration law to recognize same‐sex partners of refugees and asylees. Family Court Review 50(2), 357-371.

- Engler, P. (2009). The us immigrant rights movement (2004-ongoing). International Center on Nonviolent Conflict.

- Enriquez, L.E. (2015). Multigenerational punishment: shared experiences of undocumented immigration status within mixed-status families. Journal of Marriage and Family 77, 939-953.

- FindLaw. (2018). Arizona Immigration Law (S.B. 1070).

- Glaister, D. & MacAskill, E. (2006). US counts cost of day without immigrants.The Guardian.

- International Council on Human Rights. (2008). Climate Change and Human Rights: A Rough Guide.

- Kanstroom, D. (2010). Deportation Nation: Outsiders in American History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Koopmans, R. (2012). The Post-naturalization of immigrant rights: A theory in search of evidence. The British Journal of Sociology 63(1), 22-30.

- Koser, K. (2007). Refugees, transnationalism and the state. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 33(2), 233-254.

- McConnell, P.J. & Lopez, R.J. (1994). L.A. March against prop. 187 draws 70,000: immigration: protesters condemn wilson for backing initiative that they say promotes ‘racism, scapegoating.’ Los Angeles Times.

- McLaughlin. E.C. (2017). May day rallies turn violent as 'anarchists' in one city throw smoke bombs, police say. CNN.

- Meissner, D., Meyers, D.W., Papademetriou, D.G., & Fix, M. (2006). Immigration and America’s future: a new chapter. Migration Policy Institute.

- Menjívar, C. (2012). Transnational parenting and immigration law: central americans in the United States. Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies 38(2), 301-322.

- Milkman, R. (2000). Organizing Immigrants: The Challenge for Unions in Contemporary California. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- National Immigration Center. (2020). Supreme Court Overturns Trump Administration’s Termination of DACA.

- Office of the Press Secretary. (2012). Remarks by the president on immigration. The White House.

- Peterson Institute for International Economics. (2005). US Immigration Policy and Recent Immigration Trends.

- Prasow, A. (2012). Indefinite detention is already bad, don’t add discrimination. The Huffington Post.

- Rogerson, S. (2012). Unintended and unavoidable: The failure to protect rule and its consequences for undocumented parents and their children. Family Court Review 50(4), 580-593.

- Sabate, A. (2012). The rise of being 'undocumented and unafraid.' ABC News.

- Smith. D. (2010). Tens of thousands protest sb 1070 at Phoenix march. Tucson Sentinel.

- Smith, R. P. (2018). Guatemalan immigrant Luísa Moreno was expelled from the U.S. for her groundbreaking labor activism. Smithsonian Magazine.

- Somers, A. (2011). Voice, agency and vulnerability: he immigration of children through systems of protection and enforcement. International Migration 49(5), 3-14.

- Supreme Court of the United States. (2020). Department of Homeland Security, et al. v. Regents of the University of California, et al.

- Treviño, J. (2018). Leaving the perfect dreamer narrative behind: The immigrant rights movement in Trump’s America. Remezcla.

- United Nations. (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2006). The State of the World’s Refugees 2006: Human Displacement in the New Millennium.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2013). War’s Human Cost: UNHCR Global Trends 2013.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2013). World at War: UNHCR Global Trends Forced Displacement in 2014.

- United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. (2014). Policy Manual, Volume 12.

- United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. (2015). Lesson plan overview: female asylum applicants and gender-related claims. Asylum Officer Basic Training.

- United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. (2010). Welcome to the United States: A Guide for New Immigrants.

- United States Department of Homeland Security Press Office. (2016). Statement by secretary jeh c. johnson on southwest border security. DHS Press Release.

- United States Department of Homeland Security. (2012). Exercising Prosecutorial Discretion with Respect to Individuals Who Came to the United States as Children.

- United States Department of Justice. (2014). FY 2013 Statistics Yearbook.

- United States Department of Justice. (2006). Trafficking in Persons Report.

- United States Department of State. (2015). Myths and facts: resettling Syrian refugees. DOS Press Release.

- United States Department of State. (2012). Trafficking in Persons Report 2012.

- United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement. (2014). ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report

- University of California at Los Angeles Center for Labor Research and Education. (2008). Underground Undergrads. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Labor Research and Education.

- Vinson, L. (2020). Family separation policy continues two years after trump administration claims it ended. SPLC.

- Washington, J. and J. Olivares. (2020). Number of women alleging misconduct by ice gynecologist nearly triples. The Intercept.

- White House. (2017). Executive Order 13769.

- White House. (2018). Executive Order 13841.