3.4: Social Institutions

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 58139

- Erika Gutierrez, Janét Hund, Shaheen Johnson, Carlos Ramos, Lisette Rodriguez, & Joy Tsuhako

- Long Beach City College, Cerritos College, & Saddleback College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Immigration and the Criminal Justice System

Many people in the United States take a dim view of immigration. In a 2009 Gallup Poll, 50% of Americans thought that immigration should be decreased, 32% thought it should stay at its present level, and only 14% thought it should be increased (Morales, 2009). As Morales (2009) notes, fear of job competition is a primary reason for the concern that Americans show about immigration. Yet another reason might be their fear that immigration raises the crime rate. A 2007 Gallup Poll asked whether immigrants are making “the situation in the country better or worse, or not having much effect” for the following dimensions of our national life: food, music and the arts; the economy; social and moral values; job opportunities; taxes; and the crime situation (Newport, 2007). The percentage of respondents saying “worse” was higher for the crime situation (58%) than for any other dimension. Only 4% of respondents responded that immigration has made the crime situation better (Newport, 2007).

However, research conducted by sociologists and criminologists finds that these 4% are in fact correct: immigrants have lower crime rates than native-born Americans, and immigration has apparently helped lower the U.S. crime rate (Immigration Policy Center, 2008; Vélez, 2006; Sampson, 2008). What accounts for this surprising consequence? One reason is that immigrant neighborhoods tend to have many small businesses, churches, and other social institutions that help ensure neighborhood stability and, in turn, lower crime rates. A second reason is that the bulk of recent immigrants are Latinos, who tend to have high marriage rates and strong family ties, both of which again help ensure lower crime rates (Vélez, 2006). A final reason may be that undocumented immigrants hardly want to be deported and thus take extra care to obey the law by not committing street crime (Immigration Policy Center, 2008).

Reinforcing the immigration-lower crime conclusion, other research also finds that immigrants’ crime rates rise as they stay in the United States longer. Apparently, as the children of immigrants become more “Americanized,” their criminality increases. As one report concluded, “The children and grandchildren of many immigrants—as well as many immigrants themselves the longer they live in the United States—become subject to economic and social forces that increase the likelihood of criminal behavior” (Rumbaut & Ewing, 2007).

As the United States continues to address immigration policy, it is important that the public and elected officials have the best information possible about the effects of immigration. The findings by sociologists and other social scientists that immigrants have lower crime rates and that immigration has apparently helped lower the U.S. crime rate add an important dimension to the ongoing debate over immigration policy.

One other impact of the new wave of immigration has been increased prejudice and discrimination against the new immigrants. As noted earlier, the history of the United States is filled with examples of prejudice and discrimination against immigrants. Such problems seem to escalate as the number of immigrants increases. The past two decades have been no exception to this pattern. As the large numbers of immigrants moved into the United States, blogs and other media became filled with anti-immigrant comments, and hate crimes against immigrants increased. The Southern Poverty Law Center report summarized this trend as,

There’s no doubt that the tone of the raging national debate over immigration is growing uglier by the day. Once limited to hard-core white supremacists and a handful of border-state extremists, vicious public denunciations of undocumented brown-skinned immigrants are increasingly common among supposedly mainstream anti-immigration activists, radio hosts, and politicians. While their dehumanizing rhetoric typically stops short of openly sanctioning bloodshed, much of it implicitly encourages or even endorses violence by characterizing immigrants from Mexico and Central America as "invaders," "criminal aliens," and "cockroaches." The results are no less tragic for being predictable: although hate crime statistics are highly unreliable, numbers that are available strongly suggest a marked upswing in racially motivated violence against all Latinos, regardless of immigration status (Mock, 2007).

One example of one of these hate crimes impacted a New York City resident from Ecuador who owned a real estate company; he died in December 2008 after being beaten with a baseball bat by three men who shouted anti-Hispanic slurs. His murder was preceded by the death a month earlier of another Ecuadorean immigrant, who was attacked on Long Island by a group of males who beat him with lead pipes, chair legs, and other objects (Fahim & Zraick, 2008). An even more recent example is the mass shooting that took place at a Walmart in El Paso, Texas on August 3, 2019. This mass shooting has been linked with a spike in anti-Latinx hate crimes that "coincides with an ongoing debate over U.S. President Donald Trump’s hardline immigration policies" (Brooks, 2019).

Meanwhile, the new immigrants have included thousands who came to the United States illegally. When they are caught, many are detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in local jails, federal prisons, and other detention facilities. Immigrants who are in the United States legally but then get arrested for minor infractions are often also detained in these facilities to await deportation. It is estimated that ICE detains about 300,000 immigrants of both kinds every year. Human rights organizations say that all of these immigrants suffer from lack of food, inadequate medical care, and beatings; that many are being detained indefinitely; and that their detention proceedings lack due process.

Arizona's Senate Bill 1070

As both legal and undocumented immigrants, and with high population numbers, Mexican Americans are often the target of stereotyping, racism, and discrimination. A harsh example of this is in Arizona, where a stringent immigration law—known as SB 1070 (for Senate Bill 1070)—has caused a nationwide controversy. The law requires that during a lawful stop, detention, or arrest, Arizona police officers must establish the immigration status of anyone they suspect may be here illegally. The law makes it a crime for individuals to fail to have documents confirming their legal status, and it gives police officers the right to detain people they suspect may be in the country illegally.

To many, the most troublesome aspect of this law is the latitude it affords police officers in terms of whose citizenship they may question. Having “reasonable suspicion that the person is an alien who is unlawfully present in the United States” is reason enough to demand immigration papers (Senate Bill 1070, 2010). Critics say this law will encourage racial profiling (the illegal practice of law enforcement using race as a basis for suspecting someone of a crime), making it hazardous to be caught “Driving While Brown,” a takeoff on the legal term Driving While Intoxicated (DWI) or the slang reference of “Driving While Black.” Driving While Brown refers to the likelihood of getting pulled over just for being nonwhite.

SB 1070 has been the subject of many lawsuits, from parties as diverse as Arizona police officers, the American Civil Liberties Union, and even the federal government, which is suing on the basis of Arizona contradicting federal immigration laws (ACLU 2011). The future of SB 1070 is uncertain, but many other states have tried or are trying to pass similar measures. Do you think such measures are appropriate?

Immigration and the Government

Historical Chinese/Asian Exclusionary Policies

Many Chinese men had been recruited by the railroad companies to work on the Transcontinental Railroad—a vast, complex, engineering feat to span the continent and link the entire expanse of the middle of North America, from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. By 1887, the project was complete and many of the Chinese workers, having saved the majority of their pay, returned home, or, conversely, began to send for their families—parents, siblings, wives and children, sweethearts, cousins—beginning a steady migration stream from China to the United States. Many of these former railroad workers settled along the West Coast and began to compete, economically, with the white population of the region. Feeling serious economic pressure from the Chinese immigrants, whites on the West Coast petitioned Congress to stop migration from China. Congress complied and passed a bill titled the “Asian Exclusionary Act.” For more information regarding the use of national origin in the history of immigration policies and laws, please review Chapter 9.2.

From the 15th century through the 19th century, Japan was a xenophobic, feudal society, ostensibly governed by a God-Emperor, but in reality ruled by ruthless, powerful Shoguns. Japan’s society changed little during the four centuries of samurai culture, and it was cut off from the rest of the world in self-imposed isolation, trading only with the Portuguese, Spanish, English, and Chinese, and then not with all of them at once, often using one group as middlemen to another group. In the mid-19th century, (1854), the United States government became interested in trading directly with Japan in order to open up new export markets and to import Japanese goods at low prices uninflated by middleman add-ons. Commodore Matthew Perry was assigned to open trade between the United States and Japan. With a flotilla of war ships, Perry crossed the Pacific and berthed his ships off the coast of the Japanese capital. Perry sent letters to the emperor that were diplomatic but insistent. Perry had been ordered not to take no for an answer, and when the emperor sent Perry a negative response to the letters, Perry maneuvered his warships into positions that would allow them to fire upon the major cities of Japan. The Japanese had no armaments or ships that could compete with the Americans, and so, capitulated to Perry. Within thirty years, Japan was almost as modernized as its European counterparts. They went from feudalism to industrialism almost over night.

Within a few years of the trade treaty between the United States and Japan, a small but steady trickle of Japanese immigrants flowed across the Pacific Ocean. This migration to the West Coast of the United States meant that Japanese immigrants were in economic competition with the resident population, most of whom were white. Fears of economic loss led the whites to petition Congress to stop the flow of immigrants from Japan, and in 1911 Congress expanded the Asian Exclusionary Act to include Japanese thereby stopping all migration from Japan into the United States. In 1914, Congress passed the National Origins Act which cut off all migration from East Asia.

In 1924, anti-minority sentiment in the United States was so strong that the Ku Klux Klan had four million, proud, openly racist members thousands of whom were involved in a parade down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, DC, that was watched by thousands of Klan supporters and other Americans.

On December 7, 1941, at 7:55 A.M. local time the Japanese fleet in the South Pacific launched 600 hundred aircraft in a surprise attack against U.S. Naval forces at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Within four hours, 2,400 people, mostly military personnel had been killed, including the 1,100 men who will be entombed forever in the wreckage of the U.S.S. Arizona when it capsized during the attack. Although this was a military target, the United States was not at war when the attack occurred. In less than six months after the attack, Congress passed the Japanese Relocation Act. Below, is reproduced the order that was posted in San Francisco.

Purposes of Immigration Policy

There are five primary purposes of immigration policy (US English Foundation, 2014; Fix & Passel, 1994):

- Social: Unify citizens and legal residents with their families.

- Economic: Increase productivity and standard of living.

- Cultural: Encourage diversity, increasing pluralism and a variety of skills.

- Moral: Promote and protect human rights, largely through protecting those feeling persecution.

- Security: Control undocumented immigration and protect national security.

There are many ideological differences among the stakeholders in immigration policy and many different priorities. In order to meet the purposes listed above, policy-makers must balance the following goals against one another:

- Provide refuge to all versus recruit the best. Some stakeholders desire to provide refuge for the displaced (Permanently stamped on the Statue of Liberty are the words, “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free”). These stakeholders seek to welcome all who are separated from their families or face economic, political, or safety concerns in their current locations. Others aim to recruit those best qualified to add to the economy.

- Meet labor force needs versus protect current citizen employment. Immigrant workers are expected to make up 30-50% of the growth in the United States labor force in the coming decades (Lowell, Gelatt, & Batalova, 2006). In general, immigrants provide needed employment and do not impact the wages of the current workforce. However, there are situations (i.e., during economic downturns) where immigration can threaten the current work force’s conditions or wages.

- Enforce policy versus minimize regulatory burden and intrusion on privacy. In order to enforce immigration policy away from the border, the government must access residents’ documents. However, this threatens citizens’ privacy. When employers are required to access these documents, it also increases regulatory burden for the employers.

Key Stakeholders in Immigration Policy

There are many groups who are deeply invested in immigration and immigrant policy; their fortunes rise or fall with the policies set. These groups are called “stakeholders.” Key stakeholders in immigration and immigrant policy in the United States include the federal government, state governments, voluntary agencies, employers, families, current workers, local communities, states, and the nation as a whole.

Families

As described earlier in this chapter, one of the most common motivations for immigration is to provide a better quality of life for one’s family, either by sending money to family in another country or by bringing family to the United States (Solheim, Rojas-Garcia, Olson, & Zuiker, 2012). Immigration policy impacts these families’ abilities to migrate to access safer living conditions and seek economic stability. Further, immigration policy impacts a family’s opportunity for reunification. Reunification means that immigrants with legal status in the United States can apply for visas to bring family members to join them. Approximately two-thirds of the immigrants in the United States were sponsored by family members who migrated first and later became permanent residents (Kandel, 2014). The following quote from a Mexican immigrant epitomizes the priority of family:

My goals are to offer my family a decent life and economic stability, to guarantee them a future without serious problems, with a house, a means of transport… things that sometimes you can’t achieve in Mexico. Our goal must be for our family’s welfare, as much for my family here as for my family back there” (Solheim et al., 2012 p. 247).

Federal government

The federal government is currently solely responsible for the creation of immigration policies (Weissbrodt & Danielson, 2004). In the past, each state determined its own immigration policy according to the Articles of Confederation because it was unclear whether the United States Constitution gave the federal government power to regulate immigration (Weissbrodt & Danielson, 2011). A series of Supreme Court cases beginning in the 1850s upheld the federal government’s right to create immigration policies, arguing that the federal government must have the power to exclude non-citizens to protect the national public interest (Weissbrodt & Danielson, 2004). The Supreme Court has determined that the power to admit and to remove immigrants to the United States belongs solely to the federal government (using as precedents the uniform rule of Naturalization, Article 1.8.4, and the commerce clause, Article 1.8.3). In fact, there is no area where the legislative power of Congress is more complete (Weissbrodt & Danielson, 2004).

Immigration responsibilities were originally housed in the Treasury Department and the Department of Labor, due to its connection to foreign commerce. In the 1940s, the immigration office (later called the "INS," Immigration and Naturalization Service) was moved to the United States Department of Justice due to its connection to protecting national public interest (United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, 2010). The federal departments and agencies that implement immigration laws and policies have changed significantly since the terrorist attacks of 2001. In 2001, the United States Commission on National Security created the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which absorbed and assumed the duties of of the INS.

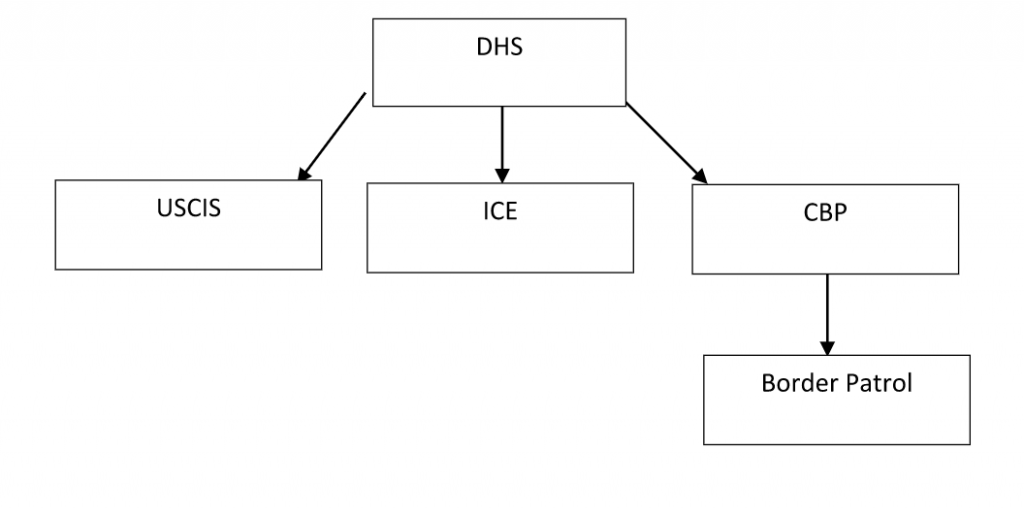

Three key agencies within DHS enforce immigration and immigrant policy (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)):

- United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS): USCIS provides immigration services, including processing immigrant visa requests, naturalization petitions, and asylum/refugee requests. Its offices are divided into four national regions: (1) Burlington, Vermont (Northeast); (2) Dallas, Texas (Central); (3) Laguna Niguel, California (West); and (4) Orlando, Florida (Southeast). The director of USCIS reports directly to the Deputy Secretary of Homeland Security. It is important to note that immigration officers, who traditionally hold law degrees, have broad discretion in deciding whether an application is complete and accurate (Weissbrodt & Danielson, 2011).

- Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE): ICE is primarily tasked with enforcing immigration laws once immigrants are inside the United States’ ICE is responsible for identifying and fixing problems in the nation’s security. This is accomplished through five operational divisions: (1) immigration investigations; (2) detention and removal; (3) Federal Protective Service; (4) international affairs; and (5) intelligence.

- United States Customs and Border Protection (USCBP): USCBP includes the Border Patrol, which is responsible for identifying and preventing undocumented aliens, terrorists, and weapons from entering the country. In addition to these responsibilities, USCBP is responsible for regulating customs and international trade to intercept drugs, illicit currency, fraudulent documents or products with intellectual property rights violations, and materials for quarantine.

State governments

Although states have no power to create immigration policy, the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA, 1996) enabled the Secretary of Homeland Security to enter into agreements with states to implement the administration and enforcement of federal immigration laws. States are also responsible for policy regarding immigrant and refugee integration. There is wide variation in how states pursue integration. Not all policies are welcoming. For example, several have passed legislation that limits access of public services to undocumented immigrants (e.g., Alabama, Georgia, Indiana, South Carolina, and Utah). In contrast, states such as Minnesota have sought to expand immigrant access to public services. These drastically different approaches have promoted consideration of this critical important task at the federal level. In late 2014, President Obama formed the “white House Task Force on New Americans” whose primary purpose is to “create welcoming communities and fully integrating immigrants and refugees” (white House, 2014). This is the first time in United States history that the executive branch of the government has undertaken such an effort.

Employers

Employers have high stakes in policy that impacts immigration, particularly as it impacts their available labor force. United States employers who recruit highly skilled workers from abroad typically sponsor their employees for permanent residence. Other employers who need a large labor force, particularly for low-skill work, often look to immigrants to fill positions.

Employers are also impacted by requirements to monitor the immigrant status of employees. Following the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986, it became illegal to knowingly employ undocumented immigrants. Many employers are now required by state law or federal contract to use the e-verify program to confirm that prospective employees are not undocumented immigrants. Such requirements aim to reduce incentives for undocumented immigration, but also pose burdens of liability and reduced labor availability for employers. The National Council of Farmer Cooperatives (2015) and the American Farm Bureau Federation oppose measures that could constrict immigration such as the e-Verify program, stating that it could have a detrimental impact on the country’s agriculture.

Current workforce

Overall, research demonstrates that immigration increases wages for United States-born workers (Ottaviano & Peri, 2008; Ottaviano & Peri, 2012; Cortes, 2008; Peri, 2010). Estimated increases in wages from immigration range from .1 to .6% (Borjas & Katz, 2007; Ottaviano & Peri, 2008; Shierholz, 2010). However, these wage increases are not unilaterally and consistently distributed across time, skill and education levels of workers. Some researchers have found that low-education workers have experienced wage decreases due to immigration, as large as 4.8% (Borjas & Katz, 2007). However, other researchers have found that among those without a high school diploma, wages decreased by approximately 1% in the short run (Shierholz, 2010; Ottaviano & Peri, 2012) but were increased slightly in the long run (Ottaviano & Peri, 2012).

Immigration generally does not decrease job opportunities for United States-born workers, and may slightly increase them (Peri, 2010). However, during economic downturns when job growth is slowed, immigration may have short-term negative effects on job availability and wages for the current workforce (Peri, 2010). Immigrants create growth in community businesses. It is nonetheless important to emphasize that the fear of non-citizens taking away employment opportunities from citizens is a primary driver for immigration laws (Weissbrodt & Danielson, 2011). While immigrants make up 16% of the labor force, they make up 18% of the business owners. Between 2000 and 2013, immigrants accounted for nearly half of overall growth of business ownership in the United States (Fiscal Policy Institute, 2015).

Communities

United States communities must provide education and health care regardless of immigration status (i.e., Plyer v. Doe, 1982). In areas with rapidly increasing numbers of immigrant workers and their families, this can tax local communities that are already overburdened (Meissner, Meyers, Papademetriou, & Fix, 2006). The Congressional Budget Office found that most state and local governments provide services to unauthorized immigrants that cost more than those immigrants generate in taxes (2007). However, studies have found that immigrants may also infuse new growth in communities and sustain current levels of living for residents (Meissner et al., 2006).

Country

Immigrants provide many benefits at a national level. Overall, immigrants create more jobs than they fill, both through demand for goods and service and entrepreneurship. Foreign labor allows growth in the labor force and sustained standard of living (Meissner et al., 2006). Even though immigrants cost more in services than they provide in taxes at a state and local governments level, immigrants pay far more in taxes than they cost in services at a national level. In particular, immigrants (both documented and undocumented) contribute billions more to Medicare through payroll taxes than they use in medical services (Zallman, Woolhandler, Himmelstein, Bor & McCormick, 2013). Additionally, many undocumented immigrants obtain social security cards that are not in their name and thereby contribute to social security, from which they will not be authorized to benefit. The Social security administration estimates that $12 billion dollars were paid into social security in 2010 alone (Goss, Wade, Skirvin, Morris, Bye, & Huston, 2013).

Current Immigration Policy

Although the decision to migrate is generally made and motivated by families, immigration policy generally focuses on the individual. For example, visas are granted to individuals, not families. In this sub-section, immigration policies that are most influential for today’s families are discussed.

1952 McCarran-Walter Act

This act and its amendments remains the basic body of immigration law. It opened immigration to all countries, establishing quotas for each (United States English Foundation, 2014). This act instituted a priority system for admitting family members of current citizens. Admission preference was given to: (1) unmarried adult sons and daughters of United States citizens; (2) spouses and unmarried sons and daughters of United States citizens; (3) professionals, scientists, and artists of exceptional ability; and (4) married adult sons and daughters of United States citizens. This meant that more families from more countries had the opportunity to reunite in the United States.

1965 Hart-Celler Immigration Act or Immigration and Nationality Act and 1978 Amendments

In this act, the national ethnicity quotas were repealed. Instead, a cap was set for each hemisphere. Once again, priority was given to family reunification and employment skills. This act also expanded the original four admission preferences to seven, adding: (5) siblings of United States citizens; (6) workers, skilled and unskilled, in occupations for which labor was in short supply in the United States; and (7) refugees from Communist-dominated countries or those affected by natural disasters. This expanded the opportunities for family members to reunite in the United States.

1990 Immigration Act

This act eased the limits on family-based immigration (United States English Foundation, 2014). It ultimately led to a 40% increase in total admissions (Fix & Passel, 1994).

DREAM Act and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals

The DREAM Act, proposed in the Senate in 2001, would allow for conditional permanent residency to immigrants who arrived in the United States as minors and have long-standing United States residency. While this bill has not been signed into law, the Obama administration signed the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) Executive Order in 2012, which provides renewable two-year work permits for those who meet the required standards. This has the largest impact on undocumented families. Many children travel to the United States without documents to be with their families, and then spend most of their lives in the United States. If the DREAM Act had passed, these children would have new opportunities to pursue higher education and jobs in the land they think of as home, without fear of deportation.

2000 Life Act and Section 245(i)

This allowed undocumented immigrants present in the United States to adjust their status to permanent resident, if they had family or employers to sponsor them (United States English Foundation, 2014).

2001 Patriot Act

The sociopolitical climate after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks drastically changed immigrant policies in the United States. This act created Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Citizenship and Immigration Services (CIS), greatly enhancing immigration enforcement.

2005 Bill

The House of Representatives passed a bill that increased enforcement at the borders, focusing on national security rather than family or economic influences (Meissner et al., 2006).

2006 Bill

The Senate passed a bill that expanded legal immigration, in order to decrease undocumented immigration (Meissner et al., 2006).

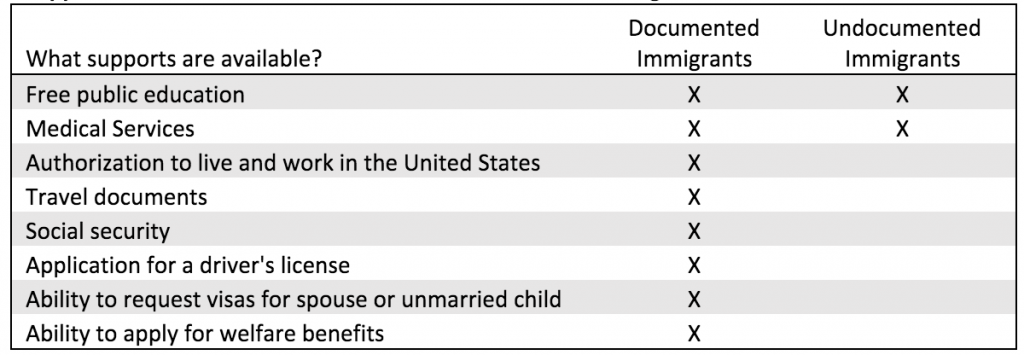

As these policies indicate, it is currently very difficult to enter the United States without documentation. There are few supports available to those who do make it across the border (see Table 3.4.8). However, the 2000 Life Act and the Dream Act provide some provisions for families who live in the United States to obtain documentation to remain together, at least temporarily.

For families who want to immigrate with documentation, current policy prioritizes family reunification. Visas are available for family members of current permanent residents, and there are no quotas on family reunification visas (see the next section). Even when family members of a current permanent resident are granted a visa, they are a long way from residency. They must wait for their priority date and process extensive paperwork. If a family wants to immigrate to the United States but does not have a family member who is a current permanent resident or a sponsoring employer, options for documented immigration are very limited.

Process of Becoming a Citizen, also called “Naturalization”

1. File a petition for an immigrant visa. The first step of documented immigration is obtaining an immigrant visa. There are a number of ways this can occur:

- For family members. A citizen or lawful permanent resident in the United States can file an immigrant visa petition for their immediate family members in other countries. In some cases, they can file a petition for a fiancé or adopted child.

- For sponsored employees. United States employers sometimes recruit skilled workers who will be hired for permanent jobs. These employers can file a visa petition for the workers.

- For immigrants from countries with low rates of immigration. The Diversity Visa Lottery program accepts applications from individuals in countries with low rates of immigration. These individuals can file an application, and visas are awarded based on random selection.

If prospective immigrants do not fall into one of these categories, their avenues for documented immigration are quite limited. For prospective immigrants who fall within one of these categories, their petition must be approved by USCIS and consular officers. However, they are still a long way from residency.

2. Wait for priority date. There is an annual limit to the number of available visas in most categories. Petitions are filed chronologically, and each prospective immigrant is given a “priority date.” The prospective immigrant must then wait until there is an available visa, based on their priority date.

3. Process paperwork. While waiting for the priority date, prospective immigrants can begin to process the paperwork. They must pay processing fees, submit a visa application form, and compile extensive additional documentation (such as evidence of income, proof of relationship, proof of United States status, birth certificates, military records, etc.) They must then complete an interview at the United States Embassy or Consulate and complete a medical exam. Once all of these steps are complete, the prospective immigrant received an immigrant visa. They can travel to the United States with a green card and enter as a lawful permanent resident (United States Visas, n.d.).

A lawful permanent resident is entitled to many of the supports of legal residents, including free public education, authorization to work in the United States, and travel documents to leave and return to the United States (FindLaw, 2018). However, permanent resident aliens remain citizens of their home country, must maintain residence in the United States in order to maintain their status, must renew their status every 10 years, and cannot vote in federal elections (USCIS, 2015).

4. Apply for citizenship. Generally, immigrants are eligible to apply for citizenship when they have been a permanent resident for at least five years, or three years if they are married to a citizen. Prospective citizens must complete an application, be fingerprinted and have a background check, complete an interview with a USCIS officer, and take an English and civics test. They must then take an Oath of Allegiance (USCIS, 2012).

Contributors and Attributions

- Gutierrez, Erika. (Santiago Canyon College)

- Ramos, Carlos. (Long Beach City College)

- Immigrant and Refugee Families (Ballard, Wieling, and Solheim) (CC BY-NC 4.0)

- Sociology (Barkan) (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

- Minority Studies (Dunn) (CC BY 4.0)

- Introduction to Sociology 2e (OpenStax) (CC BY 4.0)

Works Cited

- American Civil Liberties Union. (2011). Appellate Court Upholds Decision Blocking Arizona’s Extreme Racial Profiling Law.

- Borjas, G.J., & Katz, L.F. (2007). The evolution of the Mexican-born workforce in the united states. In G. J. Borjas, Mexican Immigration to the United States. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Brooks, B. (2019). Victims of anti-Latino hate crimes soar in U.S.: FBI report. Reuters.

- Congressional Budget Office. (2007). The impact of unauthorized immigrants on the budgets of state and local governments.

- Cortes, P. (2008). The effect of low-skilled immigration on us prices: evidence from CPI data. Journal of Political Economy 116(3), 381-422.

- Fahim, K. & Zraick, K. (2008). Killing haunts Ecuadorians’ rise in New York. The New York Times.

- FindLaw. (2018). Permanent resident rights.

- Fiscal Policy Institute. (2015). Immigrant “Main Street” Business Owners Playing an Outsized Role.

- Fix, M.E. & Passel, J.S. (1994). Immigration and immigrants: setting the record straight. Urban Institute.

- Goss, S., Wade, A., Skirvin, J.P., Morris, M., Bye, D.M., & Huston, D. (2013). Effects of unauthorized immigration on the actuarial status of the social security trust funds. Social Security Administration, Actuarial Note No. 151.

- Immigration Policy Center. (2008). From anecdotes to evidence: Setting the record straight on immigrants and crime. Washington D.C: Immigration Policy Center.

- Kandel, W.A. (2014). U.S. family-based immigration policy. Congressional Research Service Report for Congress.

- Lowell, B.L., Gelatt, J., & Batalova, J. (2006). Immigrants and labor force trends: the future, past, and present. Insight 17.

- Meissner, D., Meyers, D.W., Papademetriou, D.G., & Fix, M. (2006). Immigration and America’s future: a new chapter. Migration Policy Institute.

- Mock, B. (2007). Hate crimes against Latinos rising nationwide. Southern Poverty Law Center.

- Morales, L. (2009). Americans return to tougher immigration stance. Gallup.

- National Council of Farmer Cooperatives. (2015). E-verify.

- Newport, F. (2007). Americans have become more negative on impact of immigrants. Gallup.

- Ottaviano, G.I.P. & Peri, G. (2012). Rethinking the effect of immigration on wages. Journal of the European Economic Association 10, 152-197.

- Ottaviano, G. & Peri, G. (2008). Immigration and national wages: clarifying the theory and the empirics. NBER Working Papers, 14188. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Peri, G. (2010). The impact of immigrants in recession and economic expansion. Migration Policy Institute.

- Rumbaut, R.G. & Ewing, W.A. (2007). The myth of immigrant criminality and the paradox of assimilation: Incarceration rates among native and foreign-born men. Washington, DC: American Immigration Law Foundation.

- Sampson, R.J. (2008). Rethinking Crime and Immigration. Contexts 7(2), 28–33.

- State of Arizona. (2010). Senate Bill 1070.

- Shierholz, H. (2010). Immigration and wages: methodological advancements confirm modest gains for native workers. Economic Policy Institute Briefing Paper #255.

- Solheim, C.A., Rojas-Garcia, G., Olson, P.D., & Zuiker, V.S. (2012). Family influences on goals, remittance use, and settlement of Mexican immigrant agricultural workers in Minnesota. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 43(2), 237-259.

- United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. (2012). A Guide to Naturalization.

- United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. (2005). Information on the Legal Rights Available to Immigrant Victims of Domestic Violence in the United States and Facts about Immigrating on a Marriage-Based Visa.

- United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. (2015). USCIS Updates Welcome Guide for New Immigrants.

- United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. (2010). Welcome to the United States: A Guide for New Immigrants.

- United States English Foundation, Inc. (2014). American Immigration: An Overview.

- United States Visas. (n.d.). The Immigrant Visa Process.

- Velez, M.B. (2006). Toward an understanding of the lower rates of homicide in Latino versus Black neighborhoods: a look at chicago. In R. D. Peterson, L. J. Krivo, & J. Hagan (Eds.), The Many Colors of Crime: Inequalities of Race, Ethnicity, and Crime in America. New York, NY: New York University Press, 91-107.

- Weissbrodt, D. & Danielson, L. (2004). The Source and Scope of the Federal Power to Regulate Immigration and Naturalization.

- Weissbrodt, D. & Danielson, L. (2011). Immigration Law and Procedure in a Nutshell. 6th ed. Eagan, MN: West Publishing Company.

- White House. (2014). Presidential memorandum: Creating welcoming communities and fully integrating immigrants and refugees.

- Zallman, L., Woolhandler, S., Himmelstein, D., Bor, D., & McCormick, D. (2013). Immigrants contributed an estimated $115.2 billion more to the Medicare trust fund than they took out in 2002-2009. Health Affairs 32(6), 1153-1160.