4.2: Stereotypes and Prejudice

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 104051

- Erika Gutierrez, Janét Hund, Shaheen Johnson, Carlos Ramos, Lisette Rodriguez, & Joy Tsuhako

- Long Beach City College, Cerritos College, & Saddleback College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Stereotypes

Stereotypes are oversimplified generalizations about groups of people. Stereotypes can be based on race, ethnicity, age, gender, sexual orientation—almost any characteristic. They may be positive (usually about one’s own group, such as when women suggest they are less likely to complain about physical pain) but are often negative (usually toward other groups, such as when members of a dominant racial group suggest that a subordinate racial group is stupid or lazy). In either case, the stereotype is a generalization that doesn’t take individual differences into account.

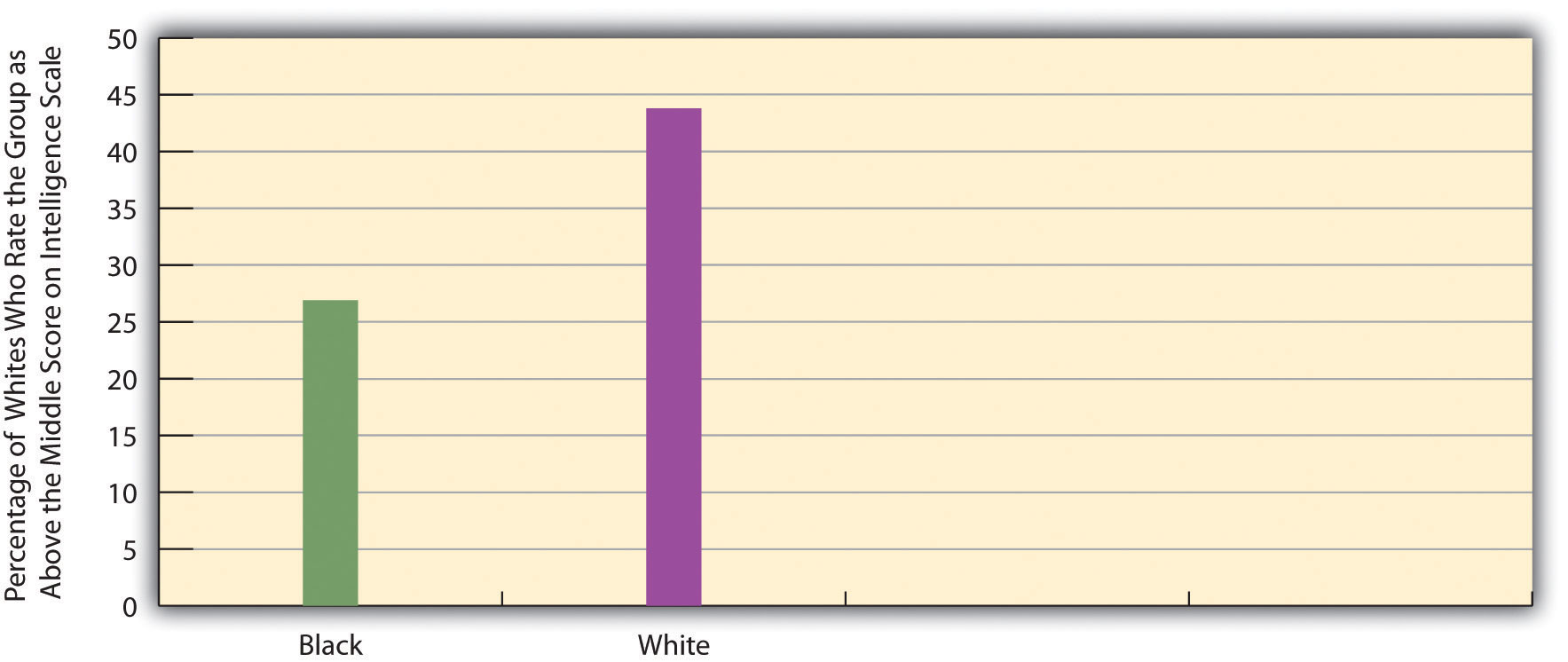

Where do stereotypes come from? In fact new stereotypes are rarely created; rather, they are recycled from subordinate groups that have assimilated into society and are reused to describe newly subordinate groups. For example, many stereotypes that are currently used to characterize Black people were used earlier in American history to characterize Irish and Eastern European immigrants. While cultural and other differences do exist among the various American racial and ethnic groups, many of the views we have of such groups are unfounded and hence are stereotypes. An example of the stereotypes that white people have of other groups appears in Figure 4.2.1 "Perceptions by Non-Latino white Respondents of the Intelligence of white and Black Americans", in which white respondents in the General Social Survey (GSS), a recurring survey of a random sample of the US population, are less likely to think Blacks are intelligent than they are to think whites are intelligent.

Stereotypes of Latinx Population

Often exhibited in negative caricatures or terms, stereotypical representation of Hispanic and Latino/a characters are typically negatively presented and attack the entire ethnic group's morality, work ethic, intelligence, or dignity. Even in non-fiction media, such as news outlets, Hispanics are usually reported on in crime, immigration, or drug-related stories than in accomplishments. The stereotypes can also differ between men and women. Hispanic or Latino men are more likely to be stereotyped as unintelligent, comedic, aggressive, sexual, and unprofessional, earning them titles as "Latin lovers," buffoons, or criminals. That often results in the individuals being characterized as working less-respectable careers, being involved in crimes (often drug-related), or being uneducated immigrants. Hispanic characters are more likely than non-Hispanic white characters to possess lower-status occupations, such as domestic workers, or be involved in drug-related crimes. Hispanic and Latina women, similarly, are typically portrayed as lazy, verbally aggressive, and lacking work ethic. The stereotypes are furthered in pseudo-autobiographical characters like George Lopez, who lacks higher education and is written around humor, and Sofia Vergara, who is portrayed as an immigrant woman marrying a rich man and is often mocked for her loud and aggressive voice.

A very common stereotype, as well as mentality, is that all Hispanic/Latino individuals have the same ethnic background, race, and culture but there are really numerous subgroups, with unique identities. Americans tend to explain all of Latin America in terms of the nationalities or countries that they know. For instance, in the Midwest and the Southwest, Latin Americans are largely perceived as Mexicans, but in the East, particularly in the New York and Boston areas, people consider Latin Americans through their limited interactions with Dominicans and Puerto Ricans. In Miami, Cubans and Central Americans are the reference group for interpreting Latin America. The idea of homogeneity is so extensive in US society that even important politicians tend to treat Latin America as a culturally-unified region. Hispanic/Latino Americans become a homogenous group, instead of their actual individual cultures, qualities, and differences.

Stereotypes of East Asians in the United States

Stereotypes of East Asians, like other ethnic stereotypes, are often portrayed in the mainstream media, cinema, music, television, literature, internet, and other forms of creative expression in American culture and society.

These stereotypes have been largely and collectively internalized by society and have mainly negative repercussions for Americans of East Asian descent and East Asian immigrants in daily interactions, current events, and government legislation. Media portrayals of East Asians often reflect an Americentric perception rather than realistic and authentic depictions of true cultures, customs and behaviors. East Asian Americans have experienced discrimination and have been victims of hate crimes related to their ethnic stereotypes, as it has been used to reinforce xenophobic sentiments.

Fictional stereotypes include Fu Manchu and Charlie Chan (representing a threatening, mysterious Asian character and an apologetic, submissive, "good" East Asian character).Asian men may be depicted as misogynistic predators, especially in WW II-era propaganda. East Asian women have been portrayed as aggressive or opportunistic sexual beings or predatory gold diggers, or as cunning "Dragon Ladies." This contrasts with the other stereotypes of servile "Lotus Blossom Babies", "China dolls", "Geisha girls", or prostitutes. Strong women may be stereotyped as Tiger Moms, and both men and women may be depicted as a model minority, with career success.

Stereotypes of Indigenous peoples

Worldwide stereotypes of Indigenous peoples include historical misrepresentations and the oversimplification of hundreds of Indigenous cultures. Negative stereotypes are associated with prejudice and discrimination that continue to impact the lives of indigenous peoples. Indigenous peoples of the Americas are commonly called Native Americans (United States excluding Alaska and Hawaii), Alaska Natives, or First Nations people (in Canada). The Circumpolar peoples, often referred to by the English term Eskimo, have a distinct set of stereotypes. Eskimo itself is an exonym, deriving from phrases that Algonquin tribes used for their northern neighbors. It is believed that some portrayals of natives, such as their depiction as bloodthirsty savages have disappeared. However, most portrayals are oversimplified and inaccurate; these stereotypes are found particularly in popular media which is the main source of mainstream images of Indigenous peoples worldwide.

The stereotyping of American Indians must be understood in the context of history which includes conquest, forced displacement, and organized efforts to eradicate native cultures, such as the boarding schools of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which separated young Native Americans from their families in order to educate and to assimilate them as European Americans.

Stereotypes of African Americans

Dating back to the period of African enslavement during the colonial era, stereotypes of African Americans are largely connected to the persistent racism and discrimination they faced while residing in the United States. Nineteenth-century minstrel shows used white actors in blackface and attire supposedly worn by African-Americans to lampoon and disparage Blacks. Some nineteenth century stereotypes, such as the sambo, are now considered to be derogatory and racist. The "Mandingo" and "Jezebel" stereotypes sexualizes African-Americans as hypersexual. The Mammy archetype depicts a motherly Black woman who is dedicated to her role working for a white family, a stereotype which dates back to Southern plantations. African-Americans are often stereotyped to have an unusual appetite for fried chicken.

In the 1980s and following decades, emerging stereotypes of Black men depicted them as drug dealers, crack addicts, hobos, and subway muggers. Jesse Jackson said media portray blacks as less intelligent. The magical Negro is a stock character who is depicted as having special insight or powers, and has been depicted (and criticized) in American cinema. Stereotypes of Black women include being depicted as welfare queens or as angry Black women who are loud, aggressive, demanding, and rude.

Explaining Prejudice

Prejudice refers to the beliefs, thoughts, feelings, and attitudes someone holds about a group. A prejudice is not based on experience; instead, it is a prejudgment, originating outside actual experience. Prejudice may be based on a person's political affiliation, sex, gender, social class, age, disability, religion, sexuality, language, nationality, criminal background, wealth, race, ethnicity, or other personal characteristic. The discussion in this section will largely focus on racial prejudice.

The 1970 documentary, Eye of the Storm, illustrates the way in which prejudice develops, by showing how defining one category of people as superior (children with blue eyes) results in prejudice against people who are not part of the favored category; Jane Elliot, then a 3rd grade teacher, conducted her "Blue Eyes/Brown Eyes" exercise to give her students a difficult, hands-on experience with prejudice and discrimination.

Where does racial and ethnic prejudice come from? Why are some people more prejudiced than others? Scholars have tried to answer these questions at least since the 1940s, when the horrors of Nazism were still fresh in people’s minds. Theories of prejudice fall into two camps, social-psychological and sociological. We will look at social-psychological explanations first and then turn to sociological explanations. We will also discuss distorted mass media treatment of various racial and ethnic groups.

Social-Psychological Explanations of Prejudice

One of the first social-psychological explanations of prejudice centered on the authoritarian personality (Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswick, Levinson, & Sanford, 1950). According to this view, authoritarian personalities develop in childhood in response to parents who practice harsh discipline. Individuals with authoritarian personalities emphasize such things as obedience to authority, a rigid adherence to rules, and low acceptance of people (out-groups) not like oneself. Many studies find strong racial and ethnic prejudice among such individuals (Sibley & Duckitt, 2008). But whether their prejudice stems from their authoritarian personalities or instead from the fact that their parents were probably prejudiced themselves remains an important question.

Another early and still popular social-psychological explanation is called frustration theory (or scapegoat theory) (Dollard, Doob, Miller, Mowrer, & Sears, 1939). In this view individuals with various problems become frustrated and tend to blame their troubles on groups that are often disliked in the real world (e.g., racial, ethnic, and religious minorities). These minorities are thus scapegoats for the real sources of people’s misfortunes. Several psychology experiments find that when people are frustrated, they indeed become more prejudiced. In one early experiment, college students who were purposely not given enough time to solve a puzzle were more prejudiced after the experiment than before it (Cowen, Landes, & Schaet, 1959).

Sociological Explanations of Prejudice

One popular sociological explanation emphasizes conformity and socialization and is called social learning theory. In this view, people who are prejudiced are merely conforming to the culture in which they grow up, and prejudice is the result of socialization from parents, peers, the news media, and other various aspects of their culture. Supporting this view, studies have found that people tend to become more prejudiced when they move to areas where people are very prejudiced and less prejudiced when they move to locations where people are less prejudiced (Aronson, 2008). If people in the South today continue to be more prejudiced than those outside the South, as we discuss later, even though legal segregation ended more than four decades ago, the influence of their culture on their socialization may help explain these beliefs.

The mass media plays a key role in how many people learn to be prejudiced. This type of learning happens because the media often present people of color in a negative light. By doing so, the media unwittingly reinforce the prejudice that individuals already have or even increase their prejudice (Larson, 2005). Examples of distorted media coverage abound. Even though poor people are more likely to be white than any other race or ethnicity, the news media use pictures of African Americans far more often than those of whites in stories about poverty. In one study, national news magazines, such as Time and Newsweek, and television news shows portrayed African Americans in almost two-thirds of their stories on poverty, even though only about one-fourth of poor people are African Americans. In the magazine stories, only 12 percent of the African Americans had a job, even though in the real world more than 40 percent of poor African Americans were working at the time the stories were written (Gilens, 1996). In a Chicago study, television news shows there depicted whites fourteen times more often in stories of good Samaritans, even though whites and African Americans live in Chicago in roughly equal numbers (Entman & Rojecki, 2001). Many other studies find that newspaper and television stories about crime and drugs feature higher proportions of African Americans as offenders than is true in arrest statistics (Surette, 2011). Studies like these show that the news media “convey the message that Black people are violent, lazy, and less civic minded” (Jackson, 1997, p. A27).

A second sociological explanation emphasizes economic and political competition and is commonly called group threat theory (Quillian, 2006). In this view, prejudice arises from competition over jobs and other resources and from disagreement over various political issues. When groups vie with each other over these matters, they often become hostile toward each other. Amid such hostility, it is easy to become prejudiced toward the group that threatens your economic or political standing. A popular version of this basic explanation is Susan Olzak’s (1992) ethnic competition theory which holds that ethnic prejudice and conflict increase when two or more ethnic groups find themselves competing for jobs, housing, and other goals.

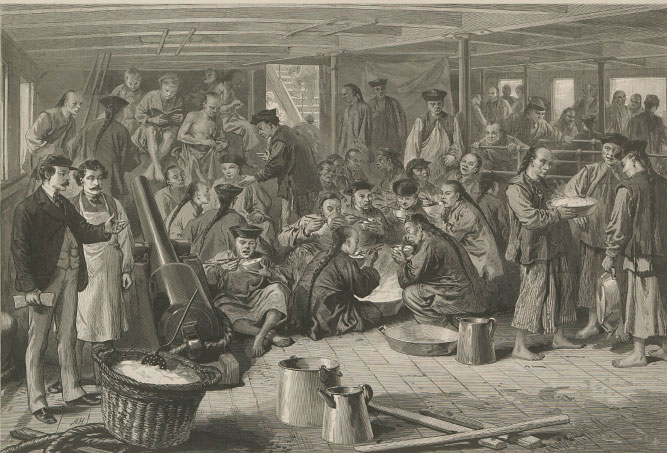

The competition explanation is the macro equivalent of the frustration/scapegoat theory already discussed. Much of the white mob violence discussed earlier stemmed from whites’ concern that the groups they attacked threatened their jobs and other aspects of their lives. Thus lynchings of African Americans in the South increased when the Southern economy worsened and decreased when the economy improved (Tolnay & Beck, 1995). Similarly, white mob violence against Chinese immigrants in the 1870s began after the railroad construction that employed so many Chinese immigrants slowed and the Chinese began looking for work in other industries. Whites feared that the Chinese would take jobs away from white workers and that their large supply of labor would drive down wages. Their assaults on the Chinese killed several people and prompted the passage by Congress of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 that prohibited Chinese immigration (Dinnerstein & Reimers, 2009).

Correlates of Prejudice

Since the 1940s, social scientists have investigated the individual correlates of racial and ethnic prejudice (Stangor, 2009). These correlates help test the theories of prejudice just presented. For example, if authoritarian personalities do produce prejudice, then people with these personalities should be more prejudiced. If frustration also produces prejudice, then people who are frustrated with aspects of their lives should also be more prejudiced. Other correlates that have been studied include age, education, gender, region of country, race, residence in integrated neighborhoods, and religiosity. We can take time here to focus on gender, education, and region of country and discuss the evidence for the racial attitudes of whites, as most studies do in view of the historic dominance of whites in the United States.

The findings on gender are rather surprising. Although women are usually thought to be more empathetic than men and thus to be less likely to be racially prejudiced, recent research indicates that the racial views of (white) women and men are in fact very similar and that the two genders are about equally prejudiced (Hughes & Tuch, 2003). This similarity supports group threat theory, outlined earlier, in that it indicates that white women and men are responding more as whites than as women or men, respectively, in formulating their racial views.

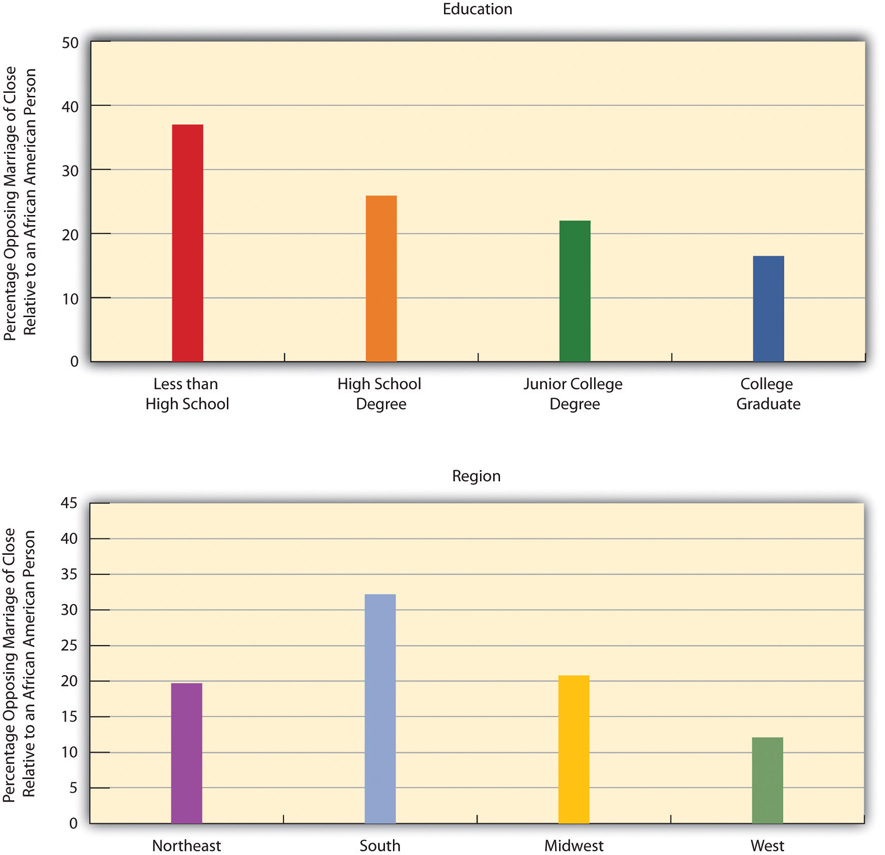

Findings on education and region of country are not surprising. Focusing again just on whites, less educated people are usually more racially prejudiced than better-educated people, and Southerners are usually more prejudiced than non-Southerners (Krysan, 2000). Evidence of these differences appears in Figure 4.2.7, which depicts educational and regional differences in a type of racial prejudice that social scientists call social distance, or feelings about interacting with members of other races and ethnicities. The General Social Survey asks respondents how they feel about a “close relative” marrying an African American. Figure 4.2.7 shows how responses by white (non-Latino) respondents to this question vary by education and by Southern residence. Whites without a high school degree are much more likely than those with more education to oppose these marriages, and whites in the South are also much more likely than their non-Southern counterparts to oppose them. To recall the sociological perspective, our social backgrounds certainly do seem to affect our attitudes.

The Changing Nature of Prejudice

Although racial and ethnic prejudice still exists in the United States, its nature has changed during the past half-century. Studies of these changes focus on whites’ perceptions of African Americans. Back in the 1940s and before, an era of overt Jim Crow racism (also called traditional or old-fashioned racism) prevailed, not just in the South but in the entire nation. This racism involved blatant bigotry, firm beliefs in the need for segregation, and the view that Blacks were biologically inferior to whites. In the early 1940s, for example, more than half of all whites thought that Blacks were less intelligent than whites, more than half favored segregation in public transportation, more than two-thirds favored segregated schools, and more than half thought whites should receive preference over Blacks in employment hiring (Schuman, Steeh, Bobo, & Krysan, 1997).

The Nazi experience and then the civil rights movement led whites to reassess their views, and Jim Crow racism gradually waned. Few whites believe today that African Americans are biologically inferior, and few favor segregation. So few whites now support segregation and other Jim Crow views that national surveys no longer include many of the questions that were asked a half-century ago.

But that does not mean that prejudice has disappeared. Many scholars say that Jim Crow racism has been replaced by a more subtle form of racial prejudice, termed laissez-faire, symbolic, or modern racism, that amounts to a “kinder, gentler, antiBlack ideology” that avoids notions of biological inferiority (Bobo, Kluegel, & Smith, 1997, p. 15; Quillian, 2006; Sears, 1988). Instead, it involves stereotypes about African Americans, a belief that their poverty is due to their cultural inferiority, and opposition to government policies to help them. Similar views exist about Latinos. In effect, this new form of prejudice blames African Americans and Latinos themselves for their low socioeconomic standing and involves such beliefs that they simply do not want to work hard.

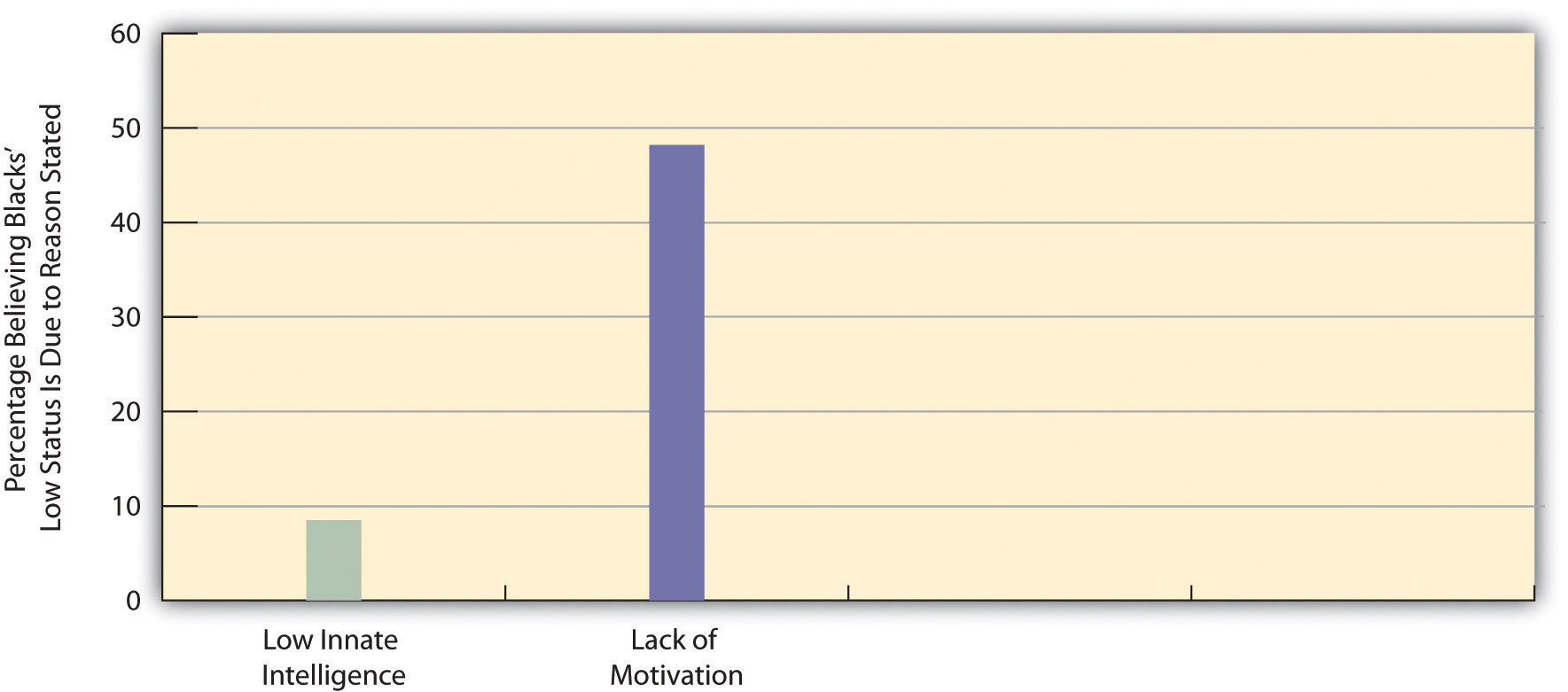

Evidence for this modern form of prejudice is seen in Figure 4.2.8, which presents whites’ responses to two General Social Survey (GSS) questions that asked, respectively, whether African Americans’ low socioeconomic status is due to their lower “in-born ability to learn” or to their lack of “motivation and will power to pull themselves up out of poverty.” While only 8.5 percent of whites attributed Blacks’ status to lower innate intelligence (reflecting the decline of Jim Crow racism), about 48 percent attributed it to their lack of motivation and willpower. Although this reason sounds “kinder” and “gentler” than a belief in Blacks’ biological inferiority, it is still one that blames African Americans for their low socioeconomic status.

Prejudice and Public Policy Preferences

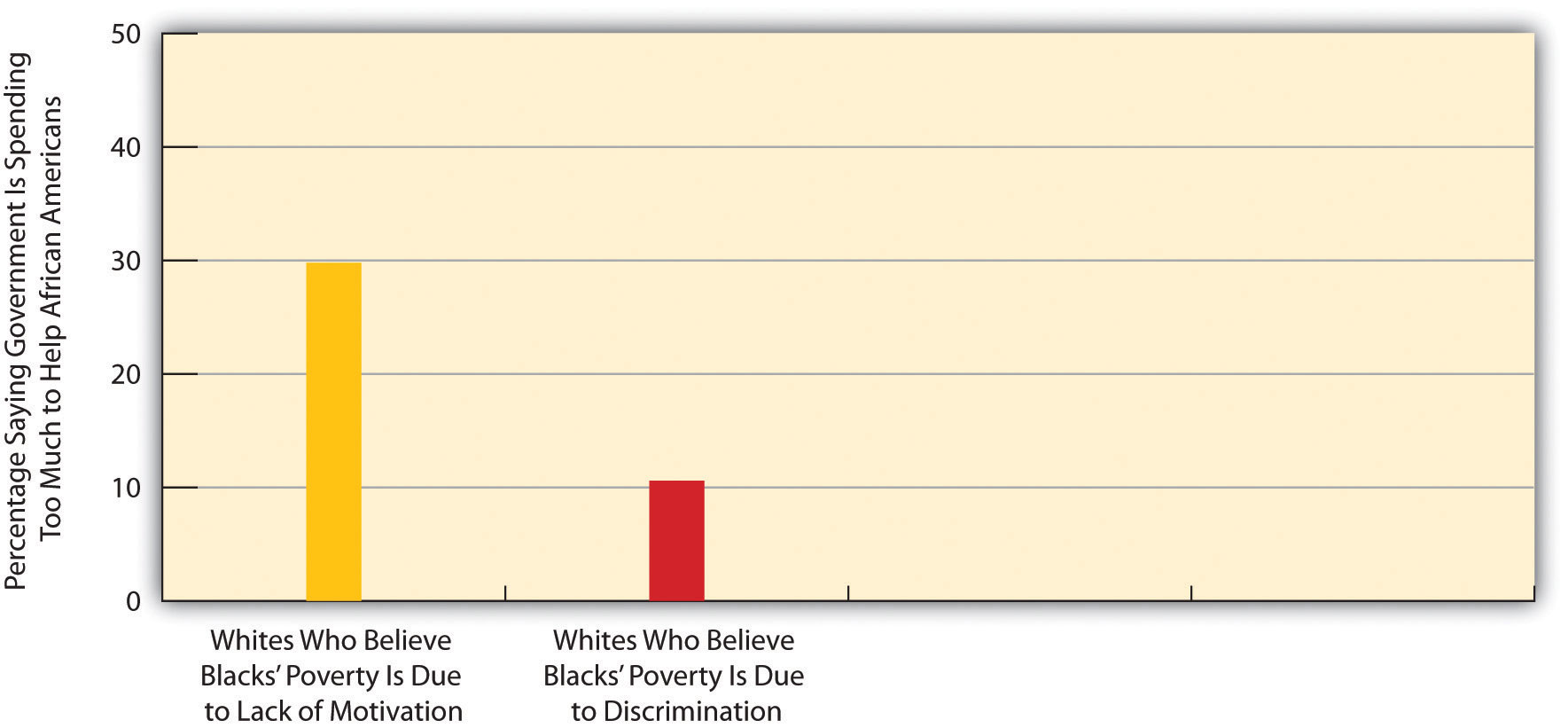

If whites do continue to believe in racial stereotypes, say the scholars who study modern prejudice, they are that much more likely to oppose government efforts to help people of color. For example, whites who hold racial stereotypes are more likely to oppose government programs for African Americans (Quillian, 2006). We can see an example of this type of effect in Figure 4.2.9, which compares two groups: whites who attribute Blacks’ poverty to lack of motivation, and whites who attribute Blacks’ poverty to discrimination. Those who cite lack of motivation are more likely than those who cite discrimination to believe the government is spending too much to help Blacks.

Racial prejudice influences other public policy preferences as well. In the area of criminal justice, whites who hold racial stereotypes or hostile feelings toward African Americans are more likely to be afraid of crime, to think that the courts are not harsh enough, to support the death penalty, to want more money spent to fight crime, and to favor excessive use of force by police (Barkan & Cohn, 2005; Unnever & Cullen, 2010).

If racial prejudice influences views on all these issues, then these results are troubling for a democratic society like the United States. In a democracy, it is appropriate for the public to disagree on all sorts of issues, including criminal justice. For example, citizens hold many reasons for either favoring or opposing the death penalty. But is it appropriate for racial prejudice to be one of these reasons? To the extent that elected officials respond to public opinion, as they should in a democracy, and to the extent that racial prejudice affects public opinion, then racial prejudice may be influencing government policy on criminal justice and on other issues. In a democratic society, it is unacceptable for racial prejudice to have this effect.

Implicit Bias

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\): Microaggressions. (Courtesy of Shutterstock.com)

- Implicit biases are attitudes or stereotypes that unconsciously affect our actions, decisions, and understanding.

- Implicit biases can be positive (a preference for something or someone) or negative (an aversion to or fear of something or someone).

- Implicit biases are different from known biases that people may choose to conceal for social or political reasons. In fact, implicit biases often conflict with a person’s explicit and/or declared beliefs.

- Implicit biases are formed over a lifetime as a result of exposure to direct and indirect messages. The media plays a large role in this formation process.

- Implicit biases are pervasive: everyone has them.

- Implicit biases are changeable, but research shows that this process takes time, intention, and training.

In this video, CNN journalist Van Jones gives a brief overview of implicit bias and references some of the ways it has manifested in recent events.

The Kirwan Institute is a leader in the field of implicit bias research. Watch their video, in which they explore some of the ways that individual impacts of implicit bias can compound to create large negative impacts for people of color.

Microaggressions

Implicit biases can impact our relationships and interactions with each other in many ways, some of which are described in the research findings listed above. One way that implicit biases can manifest is in the form of microaggressions: subtle verbal or nonverbal insults or denigrating messages communicated toward a marginalized person, often by someone who may be well-intentioned but unaware of the impact their words or actions have on the target. Examples of common microaggressions include statements like:

- Where are you really from?

- What are you?

- You don’t act like a normal Black person.

- You’re really pretty for a dark-skinned girl.

Microaggressions can be based on any aspect of a marginalized person’s identity (for example, sexuality, religion, or gender). Individual microaggressions may not be devastating to the person experiencing them; however, their cumulative effects over time can be large. The Tumblr blog Microaggressions, which aims to “mak[e] visible the ways in which social difference is produced and policed in everyday lives,” describes this as follows:

Often, [microaggressions] are never meant to hurt – acts done with little conscious awareness of their meanings and effects. Instead, their slow accumulation during a childhood and over a lifetime is in part what defines a marginalized experience, making explanation and communication with someone who does not share this identity particularly difficult. Social others are microaggressed hourly, daily, weekly, monthly.

In his research, Dr. Derald Wing Sue found that BIPOC (Black Indigenous People of Color) experience microaggressions every day – from the time they get up in the morning until they go to bed at night. In his workshops, Sue asks white people in the room these questions:

Do you know what it’s like to be a Black person in this society where you go into a subway and you sit down and people never sit next to you? Do you know what it’s like to pass a man or a woman, and they suddenly clutch their purses more tightly?

As he notes, many whites have never thought about how this feels because they don’t live this reality. It is invisible to them. By asking this question, Sue’s goal is to make the invisible visible, to get white people (and all people) to “see” the microaggressions BIPOC experience on a daily basis, and to challenge them to understand how those microaggressions negatively impact the daily lived experiences of BIPOC.

To learn more about how young people experience microaggressions, watch this video, in which college students share their personal stories related to this issue.

What's the Impact on BIPOC?

Pervasive implicit bias and microaggressions do more than simply cause BIPOC to “feel bad.” Constant exposure to racism in both implicit and explicit forms can have cumulative and serious impacts on BIPOC. Researchers are only now beginning to identify and understand some of these impacts. For example, scientists have begun linking prolonged racism-related stress to racial health disparities such as differences in maternal mortality rates between Black and white women. Other racial health disparities, such as differing rates of asthma and diabetes across racial groups, may also be linked to the stress impact of racism. Stress hormones, while harmless in small doses, are toxic with prolonged exposure, and can cause permanent damage to the nervous, cardiovascular, immune, and endocrine systems.

In addition to health disparities, the so-called “racial achievement gap” in education has also been attributed at least in part to the presence of implicit bias, stereotypes, and microaggressions. In the 1990s, psychologists Claude Steele and Joshua Aronson provided empirical evidence for the impact of stereotype threat (discussed earlier as understood by critical race theory in Chapter 2.2) on academic performance. The idea behind stereotype threat is that awareness of negative stereotypes about one’s racial group raises stress and self-doubt among students, who then perform worse. Over two decades of data show that stereotype threat is common and consequential. For a summary of this phenomenon and related studies, read the American Psychological Association’s “Research in Action” page.

In her research, Dr. Patricia F. Katopol looks at the impact of stereotype threat on the use of library reference services by BIPOC, specifically African American college students at primarily white institutions. Katopol argues that stereotype threat may be an element of information anxiety – an element that leads many Black students to attempt to find all of the information they need on their own rather than having to interact with librarians who they perceive as judging them. To learn more about stereotype threat in library settings, read her article Avoiding the Reference Desk: Stereotype Threat in Library Leadership & Management, an open-source journal.

In each of these cases, current research is challenging our notions of cause and effect when it comes to implicit bias, stereotypes, racism, and life outcomes. Rather than attributing the causes of disparate life outcomes to inherent racial differences, this research asks us to consider racism itself as the cause. Kendi (2020) detests the use of the word "microaggression," as he argues it is actually racist abuse (racism) and should be labeled as such.

Key Takeaways

- Social-psychological explanations of prejudice emphasize authoritarian personalities and frustration, while sociological explanations emphasize social learning and group threat.

- Education and region of residence are related to racial prejudice among whites; prejudice is higher among whites with lower levels of formal education and among whites living in the South.

- Jim Crow racism has been replaced by symbolic or modern racism that emphasizes the cultural inferiority of people of color.

- Racial prejudice among whites is linked to certain views they hold about public policy. Prejudice is associated with lower support among whites for governmental efforts to help people of color and with greater support for a more punitive criminal justice system.

- Implicit biases, microaggressions, and stereotypes are interrelated concepts. Implicit biases are developed through exposure to stereotypes and other forms of misinformation over time. These implicit biases can then lead well-intentioned people to commit microaggressions against people of color, Native people, and others with marginalized identities.

Thinking Sociologically

- Think about the last time you heard someone say a remark that was racially prejudiced. What was said? What was your reaction?

- The text argues that it is inappropriate in a democratic society for racial prejudice to influence public policy. Do you agree with this argument? Why or why not?

Contributors and Attributions

- Johnson, Shaheen. (Long Beach City College)

- Rodriguez, Lisette. (Long Beach City College)

- Introduction to Sociology 2e (OpenStax) (CC BY 4.0)

- Project READY: Reimagining Equity & Access for Diverse Youth (Institute of Museum and Library Services) (CC BY 4.0)

- Social Problems: Continuity and Change v.1.0 (saylordotorg) (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Stereotypes_of_indigenous_peoples_of_Canada_and_the_United_States (Wikipedia) (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Stereotypes_of_East_Asians_in_the_United_States (Wikipedia) (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Stereotypes_of_African_Americans (Wikipedia) (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Stereotypes_of_Hispanic_and_Latino_Americans_in_the_United_States (Wikipedia) (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Works Cited

- Adorno, T.W., Frenkel-Brunswick, E., Levinson, D.J., & Sanford, R.N. (1950). The Authoritarian Personality. New York, NY: Harper.

- Aronson, E. (2008). The Social Animal (10th ed.). New York, NY: Worth.

- Barkan, S.E., & Cohn, S.F. (2005). Why whites favor spending more money to fight crime: The role of racial prejudice. Social Problems, 52, 300–314.

- Bobo, L., Kluegel, J.R., & Smith, R.A. (1997). Laissez-faire racism: The crystallization of a kinder, gentler, antiBlack ideology. In S.A. Tuch & J.K. Martin (Eds.), Racial Attitudes in the 1990s: Continuity and change (pp. 15–44). Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Cowen, E.L., Landes, J., & Schaet, D.E. (1959). The effects of mild frustration on the expression of prejudiced attitudes. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 64, 33–38.

- Dinnerstein, L., & Reimers, D.M. (2009). Ethnic Americans: A History of Immigration. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Dollard, J., Doob, L.W., Miller, N.E., Mowrer, O.H., & Sears, R.R. (1939). Frustration and Aggression. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Entman, R.M., & Rojecki, A. (2001). The Black Image in the White Mind. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Gilens, M. (1996). Race and poverty in America: Public misperceptions and the American news media. Public Opinion Quarterly, 60, 515–541.

- Hughes, M., & Tuch, S.A. (2003). Gender differences in whites’ racial attitudes: Are women’s attitudes really more favorable? Social Psychology Quarterly, 66, 384–401.

- Jackson, D.Z. (1997, December 5). Unspoken during race talk. The Boston Globe, p. A27.

- Krysan, M. (2000). Prejudice, politics, and public opinion: Understanding the sources of racial policy attitudes. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 135–168.

- Larson, S.G. (2005). Media & Minorities: The Politics of Race in News and Entertainment. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Olzak, S. (1992). The Dynamics of Ethnic Competition and Conflict. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Quillian, L. (2006). New approaches to understanding racial prejudice and discrimination. Annual Review of Sociology, 32, 299–328.

- Peters, W., Beutel, B., Elliott, J., ABC News Productions., & Admire Entertainment, Inc. (2003). The Eye of the Storm. Palisades, NY: Admire Productions.

- Schuman, H., Steeh, C., Bobo, L., & Krysan, M. (1997). Racial Attitudes in America: Trends and Interpretations (Rev. ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Sears D. (1988). Symbolic Racism. In P.A. Katz & D.A. Taylor (Eds.), Eliminating Racism: Profiles in Controversy (pp. 53–84). New York, NY: Plenum

- Sibley, C.G., & Duckitt, J. (2008). Personality and prejudice: A meta-analysis and theoretical review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12, 248–279.

- Stangor, C. (2009). The study of stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination within social psychology: A quick history of theory and research. In T. D. Nelson (Ed.), Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination (pp. 1–22). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Surette, R. (2011). Media, Crime, and Criminal Justice: Images, Realities, and Policies (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Tolnay, S.E., & Beck, E.M. (1995). A Festival of Violence: An Analysis of Southern Lynchings, 1882–1930. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Unnever, J.D., & Cullen, F.T. (2010). The social sources of Americans’ punitiveness: A test of three competing models. Criminology, 48, 99–129.