4.3: Discrimination

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 104052

- Erika Gutierrez, Janét Hund, Shaheen Johnson, Carlos Ramos, Lisette Rodriguez, & Joy Tsuhako

- Long Beach City College, Cerritos College, & Saddleback College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Discrimination

Often racial and ethnic prejudice leads to discrimination against the subordinate racial and ethnic groups in a given society. Discrimination in this context refers to the arbitrary denial of rights, privileges, and opportunities to members of these groups. The use of the word arbitrary emphasizes that these groups are being treated unequally not because of their lack of merit but because of their race and ethnicity.

Usually prejudice and discrimination go hand-in-hand, but Robert Merton (1949) stressed this is not always so. Sometimes we can be prejudiced and not discriminate, and sometimes we might not be prejudiced and still discriminate. Table 4.3.1 illustrates his perspective. The top-left cell and bottom-right cell consist of people who behave in ways we would normally expect. The top-left one consists of “active bigots,” in Merton’s terminology, people who are both prejudiced and discriminatory. An example of such a person is the white owner of an apartment building who dislikes people of color and refuses to rent to them. The bottom-right cell consists of “all-weather liberals,” as Merton called them, people who are neither prejudiced nor discriminatory. An example would be someone who holds no stereotypes about the various racial and ethnic groups and treats everyone the same regardless of her or his background.

| Prejudiced? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| Discriminates? | ||

| Yes | Active bigots | Fair-weather liberals |

| No | Timid bigots | All-weather liberals |

The remaining two cells of Table 4.3.1 are the more unexpected ones. On the bottom left, we see people who are prejudiced but who nonetheless do not discriminate; Merton called them “timid bigots.” An example would be white restaurant owners who do not like people of color but still serve them anyway because they want their business or are afraid of being sued if they do not serve them. At the top right, we see “fair-weather liberals,” or people who are not prejudiced but who still discriminate. An example would be white store owners in the South during the segregation era who thought it was wrong to treat Blacks worse than whites but who still refused to sell to them because they were afraid of losing white customers.

Explaining Racial and Ethnic Inequality

Biological Inferiority

As discussed in Chapter 1.2, one long-standing (racist) explanation is that Blacks and other people of color are biologically inferior: They are naturally less intelligent and have other innate flaws that keep them from getting a good education and otherwise doing what needs to be done to achieve the American Dream. As discussed earlier, this racist view is no longer common today. However, whites historically used this belief to justify slavery, lynchings, the harsh treatment of Native Americans in the 1800s, and lesser forms of discrimination. In 1994, Richard J. Herrnstein and Charles Murray revived this view in their controversial book, The Bell Curve (Herrnstein & Murray, 1994), in which they argued that the low IQ scores of African Americans, and of poor people more generally, reflect their genetic inferiority in the area of intelligence. African Americans’ low innate intelligence, they said, accounts for their poverty and other problems. Although the news media gave much attention to their book, few scholars agreed with its views, and many condemned the book’s argument as a racist way of “blaming the victim” (Gould, 1994).

Cultural Deficiencies

Another explanation of racial and ethnic inequality focuses on supposed cultural deficiencies of African Americans and other people of color (Murray, 1984). These deficiencies include a failure to value hard work and, for African Americans, a lack of strong family ties, and are said to account for the poverty and other problems facing these minorities. As we saw earlier, more than half of non-Latino whites think that Blacks’ poverty is due to their lack of motivation and willpower. Ironically some scholars find support for this cultural deficiency view in the experience of many Asian Americans, whose success is often attributed to their culture’s emphasis on hard work, educational attainment, and strong family ties (Min, 2005). If that is true, these scholars say, then the lack of success of other people of color stems from the failure of their own cultures to value these attributes.

How accurate is the cultural deficiency argument? Whether people of color have “deficient” cultures remains hotly debated (Bonilla-Silva, 2009). Many social scientists find little or no evidence of cultural problems in minority communities and say the belief in cultural deficiencies is an example of symbolic racism that blames the victim. Citing survey evidence, they say that poor people of color value work and education for themselves and their children at least as much as wealthier white people do (Holland, 2011; Muhammad, 2007). Yet other social scientists, including those sympathetic to the structural problems facing people of color, believe that certain cultural problems do exist, but they are careful to say that these cultural problems arise out of the structural problems. For example, Elijah Anderson (1999) wrote that a “street culture” or “oppositional culture” exists among African Americans in urban areas that contributes to high levels of violent behavior, but he emphasized that this type of culture stems from the segregation, extreme poverty, and other difficulties these citizens face in their daily lives and helps them deal with these difficulties. Thus even if cultural problems do exist, they should not obscure the fact that structural problems are responsible for the cultural ones.

Structural Problems

A third explanation for US racial and ethnic inequality is based in conflict theory and reflects the blaming-the-system approach. This view attributes racial and ethnic inequality to structural problems, including institutional and individual discrimination, a lack of opportunity in education and other spheres of life, and the absence of jobs that pay an adequate wage (Feagin, 2006). Segregated housing, for example, prevents African Americans from escaping the inner city and from moving to areas with greater employment opportunities. Employment discrimination keeps the salaries of people of color much lower than they would be otherwise. The schools that many children of color attend every day are typically overcrowded and underfunded. As these problems continue from one generation to the next, it becomes very difficult for people already at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder to climb up it because of their race and ethnicity.

Individual Discrimination

The discussion so far has centered on individual discrimination, or discrimination that individuals practice in their daily lives, usually because they are prejudiced but sometimes even if they are not prejudiced. Individual discrimination is common, as Joe Feagin (1991), a former president of the American Sociological Association, found when he interviewed middle-class African Americans about their experiences. Many of the people he interviewed said they had been refused service, or at least received poor service, in stores or restaurants. Others said they had been harassed by the police, and even put in fear of their lives, just for being Black. Feagin concluded that these examples are not just isolated incidents but rather reflect the larger racism that characterizes US society.

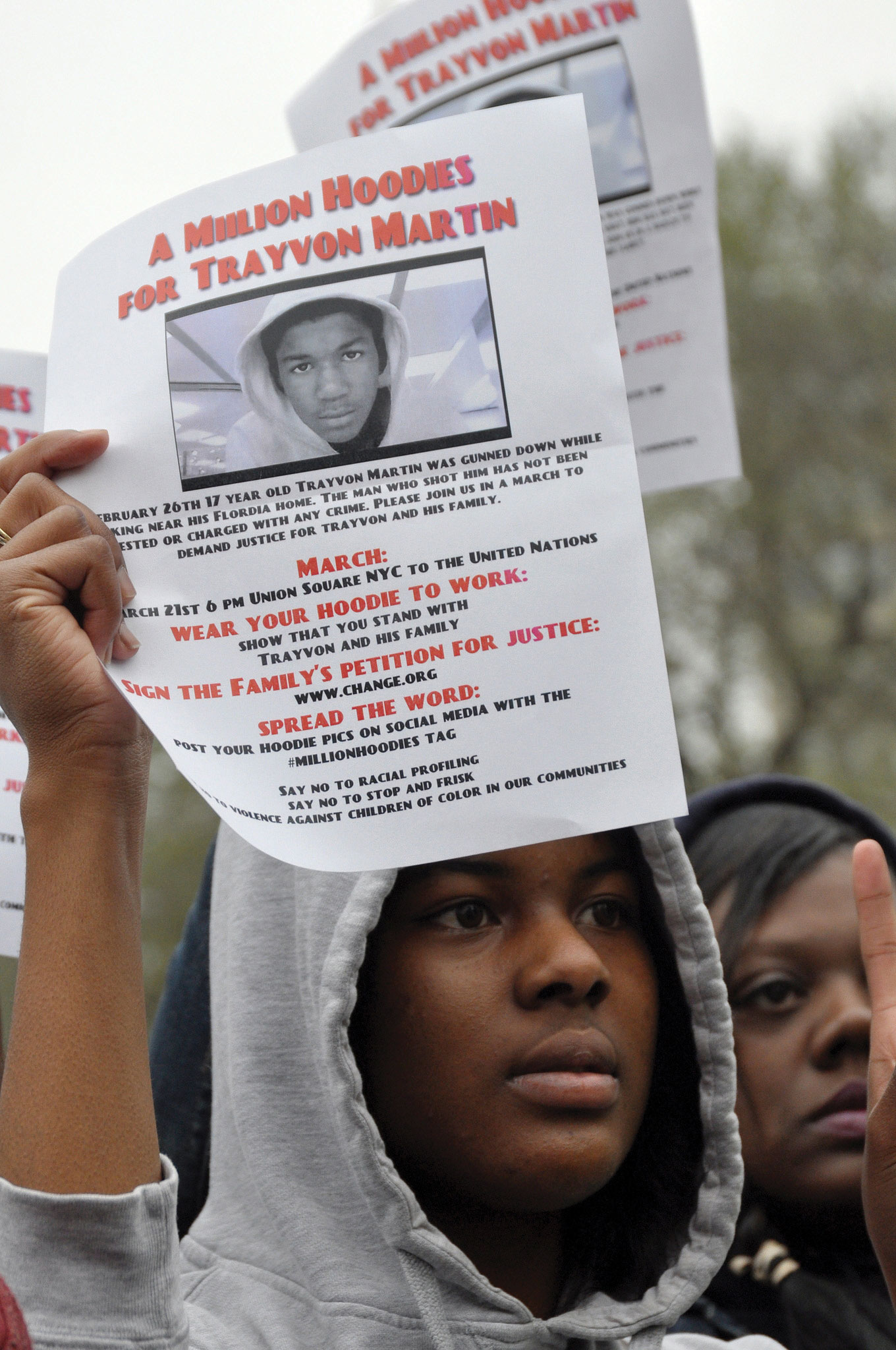

To many observers, the fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin in February 2012 was a deadly example of individual discrimination. Martin, a 17-year-old African American, was walking in a gated community in Sanford, Florida, as he returned from a 7-Eleven with a bag of Skittles and some iced tea. An armed neighborhood watch volunteer, George Zimmerman, called 911 and said Martin looked suspicious. Although the 911 operator told Zimmerman not to approach Martin, Zimmerman did so anyway; within minutes Zimmerman shot and killed the unarmed Martin and later claimed self-defense. According to many critics of this incident, Martin’s only “crime” was “walking while Black.” As an African American newspaper columnist observed, “For every Black man in America, from the millionaire in the corner office to the mechanic in the local garage, the Trayvon Martin tragedy is personal. It could have been me or one of my sons. It could have been any of us” (Robinson, 2012).

Much individual discrimination occurs in the workplace, as sociologist Denise Segura (Segura, 1992) documented when she interviewed 152 Mexican American women working in white-collar jobs at a public university in California. More than 40 percent of the women said they had encountered workplace discrimination based on their ethnicity and/or gender, and they attributed their treatment to stereotypes held by their employers and coworkers. Along with discrimination, they were the targets of condescending comments like “I didn’t know that there were any educated people in Mexico that have a graduate degree.”

Institutional Discrimination

Individual discrimination is important to address, but at least as consequential in today’s world is institutional discrimination, or discrimination that pervades the practices of whole institutions, such as housing, medical care, law enforcement, employment, and education. This type of discrimination does not just affect a few isolated people of color. Instead, it affects large numbers of individuals simply because of their race or ethnicity. Sometimes institutional discrimination is also based on gender, disability, and other characteristics.

In the area of race and ethnicity, institutional discrimination often stems from prejudice, as was certainly true in the South during segregation. However, just as individuals can discriminate without being prejudiced, so can institutions when they engage in practices that seem to be racially neutral but in fact have a discriminatory effect. Individuals in institutions can also discriminate without realizing it. They make decisions that turn out, upon close inspection, to discriminate against people of color even if they did not mean to do so.

The bottom line is this: Institutions can discriminate even if they do not intend to do so. Consider height requirements for police. Before the 1970s, police forces around the United States commonly had height requirements, say five feet ten inches. As women began to want to join police forces in the 1970s, many found they were too short. The same was true for people from some racial/ethnic backgrounds, such as Latinos, whose stature is smaller on the average than that of non-Latino whites. Of course, even many white males were too short to become police officers, but the point is that even more women, and even more men of certain ethnicities, were too short.

This gender and ethnic difference is not, in and of itself, discriminatory as the law defines the term. The law allows for bona fide (good faith) physical qualifications for a job. As an example, we would all agree that someone has to be able to see to be a school bus driver; sight therefore is a bona fide requirement for this line of work. Thus even though people who are blind cannot become school bus drivers, the law does not consider such a physical requirement to be discriminatory.

But were the height restrictions for police work in the early 1970s bona fide requirements? Women and members of certain ethnic groups challenged these restrictions in court and won their cases, as it was decided that there was no logical basis for the height restrictions then in effect. In short (pun intended), the courts concluded that a person did not have to be five feet ten inches to be an effective police officer. In response to these court challenges, police forces lowered their height requirements, opening the door for many more women, Latino men, and some other men to join police forces (Appier, 1998). Whether police forces back then intended their height requirements to discriminate, or whether they honestly thought their height requirements made sense, remains in dispute. Regardless of the reason, their requirements did discriminate.

Institutional discrimination affects the life chances of people of color in many aspects of life today. To illustrate this, we turn briefly to some examples of institutional discrimination that have been the subject of government investigation and scholarly research.

Health Care

People of color have higher rates of disease and illness than whites. One question that arises is why their health is worse. One possible answer involves institutional discrimination based on race and ethnicity.

Several studies use hospital records to investigate whether people of color receive optimal medical care, including coronary bypass surgery, angioplasty, and catheterization. After taking the patients’ medical symptoms and needs into account, these studies find that African Americans are much less likely than whites to receive the procedures just listed. This is true when poor Blacks are compared to poor whites and also when middle-class Blacks are compared to middle-class whites (Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2003). In a novel way of studying race and cardiac care, one study performed an experiment in which several hundred doctors viewed videos of African American and white patients, all of whom, unknown to the doctors, were actors. In the videos, each “patient” complained of identical chest pain and other symptoms. The doctors were then asked to indicate whether they thought the patient needed cardiac catheterization. The African American patients were less likely than the white patients to be recommended for this procedure (Schulman et al., 1999).

Why does discrimination like this occur? It is possible, of course, that some doctors are racists and decide that the lives of African Americans just are not worth saving, but it is far more likely that they have unconscious racial biases that somehow affect their medical judgments. Regardless of the reason, the result is the same: African Americans are less likely to receive potentially life-saving cardiac procedures simply because they are Black. Institutional discrimination in health care, then, is literally a matter of life and death.

It is also significant to note that the Latinx population has the highest uninsured rates of any racial or ethnic group within the United States. In 2017, the Census Bureau reported that 49.0% of Latinx had private insurance coverage, as compared to 75.4% for non-Latinx whites (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2019). In 2017, 38.2% of all Hispanics had public health insurance coverage, as compared to 33.7% for non-Hispanic whites (ibid). Most Americans have health insurance through their employers, as the country does not ensure that all Americans have insurance. This "business as usual" practice has had a disproportionately negative impact on the Latinx population. As explained in an American Medical Association article, "the structural drivers that have led to health inequity in Latinx communities have been exacerbated by COVID-19 and have contributed to the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on these communities" (Robeznieks, 2020).

Mortgages, Redlining, and Residential Segregation

When loan officers review mortgage applications, they consider many factors, including the person’s income, employment, and credit history. The law forbids them to consider race and ethnicity. Yet African Americans and Latinos are more likely than whites to have their mortgage applications declined (Blank, Venkatachalam, McNeil, & Green, 2005). Because members of these groups tend to be poorer than whites and to have less desirable employment and credit histories, the higher rate of mortgage rejections may be appropriate, albeit unfortunate.

To control for this possibility, researchers take these factors into account and in effect compare whites, African Americans, and Latinos with similar incomes, employment, and credit histories. Some studies are purely statistical, and some involve white, African American, and Latino individuals who independently visit the same mortgage-lending institutions. Both types of studies find that African Americans and Latinos are still more likely than whites with similar qualifications to have their mortgage applications rejected (Turner, Freiberg, Godfrey, Herbig, Levy, & Smith, 2002). We will probably never know whether loan officers are consciously basing their decisions on racial prejudice, but their practices still amount to racial and ethnic discrimination whether the loan officers are consciously prejudiced or not.

There is also evidence of banks rejecting mortgage applications for people who wish to live in certain urban, supposedly high-risk neighborhoods, and of insurance companies denying homeowner’s insurance or else charging higher rates for homes in these same neighborhoods. Practices like these that discriminate against houses in certain neighborhoods are called redlining, and they also violate the law (Ezeala-Harrison, Glover, & Shaw-Jackson, 2008). Because the people affected by redlining tend to be people of color, redlining, too, is an example of institutional discrimination.

Mortgage rejections and redlining contribute to another major problem facing people of color: residential segregation. Housing segregation is illegal but is nonetheless widespread because of mortgage rejections and other processes that make it very difficult for people of color to move out of segregated neighborhoods and into unsegregated areas. African Americans in particular remain highly segregated by residence in many cities, much more so than is true for other people of color. The residential segregation of African Americans is so extensive that it has been termed hypersegregation and more generally called American apartheid (Massey & Denton, 1993).

In addition to mortgage rejections, a pattern of subtle discrimination by realtors and homeowners makes it difficult for African Americans to find out about homes in white neighborhoods and to buy them (Pager, 2008). For example, realtors may tell African American clients that no homes are available in a particular white neighborhood, but then inform white clients of available homes. The now routine posting of housing listings on the Internet might be reducing this form of housing discrimination, but not all homes and apartments are posted, and some are simply sold by word of mouth to avoid certain people learning about them.

The hypersegregation experienced by African Americans cuts them off from the larger society, as many rarely leave their immediate neighborhoods, and results in concentrated poverty, where joblessness, crime, and other problems reign. For several reasons, then, residential segregation is thought to play a major role in the seriousness and persistence of African American poverty (Rothstein, 2012; Stoll, 2008).

Employment Discrimination

Title VII of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 banned racial discrimination in employment, including hiring, wages, and firing. However, African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans still have much lower earnings than whites. Several factors explain this disparity. Despite Title VII, however, an additional reason is that people of color continue to face discrimination in hiring and promotion (Hirsh & Cha, 2008). It is again difficult to determine whether such discrimination stems from conscious prejudice or from unconscious prejudice on the part of potential employers, but it is racial discrimination nonetheless.

A now-classic field experiment documented such discrimination. Sociologist Devah Pager (2003) had young white and African American men apply independently in person for entry-level jobs. They dressed the same and reported similar levels of education and other qualifications. Some applicants also admitted having a criminal record, while other applicants reported no such record. As might be expected, applicants with a criminal record were hired at lower rates than those without a record. However, in striking evidence of racial discrimination in hiring, African American applicants without a criminal record were hired at the same low rate as the white applicants with a criminal record.

Dimensions of Racial and Ethnic Inequality

Racial and ethnic inequality manifests itself in all walks of life. The individual and institutional discrimination just discussed is one manifestation of this inequality. We can also see stark evidence of racial and ethnic inequality in various government statistics. Sometimes statistics lie, and sometimes they provide all too true a picture; statistics on racial and ethnic inequality fall into the latter category. Table 4.3.5 presents data on racial and ethnic differences in income, education, and health.

| White | African American | Latino | Asian | Native American | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median family income, 2010 ($) | 68,818 | 39,900 | 41,102 | 76,736 | 39,664 |

| Persons who are college educated, 2010 (%) | 30.3 | 19.8 | 13.9 | 52.4 | 14.9 (2008) |

| Persons in poverty, 2010 (%) | 9.9 (non-Latino) | 27.4 | 26.6 | 12.1 | 28.4 |

| Infant mortality (number of infant deaths per 1,000 births), 2006 | 5.6 | 12.9 | 5.4 | 4.6 | 8. |

The picture presented by Table 4.3.5 is clear: US racial and ethnic groups differ dramatically in their life chances. Compared to whites, for example, African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans have much lower family incomes and much higher rates of poverty; they are also much less likely to have college degrees. In addition, African Americans and Native Americans have much higher infant mortality rates than whites: Black infants, for example, are more than twice as likely as white infants to die.

Although Table 4.3.5 shows that African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans fare much worse than whites, it presents a more complex pattern for Asian Americans. Compared to whites, Asian Americans have higher family incomes and are more likely to hold college degrees, but they also have a higher poverty rate. Thus many Asian Americans do relatively well, while others fare relatively worse, as just noted. Although Asian Americans are often viewed as a “model minority,” meaning that they have achieved economic success despite not being white, some Asians have been less able than others to climb the economic ladder. Moreover, stereotypes of Asian Americans and discrimination against them remain serious problems (Chou & Feagin, 2008). Even the overall success rate of Asian Americans obscures the fact that their occupations and incomes are often lower than would be expected from their educational attainment. They thus have to work harder for their success than whites do (Hurh & Kim, 1999).

The Increasing Racial/Ethnic Wealth Gap

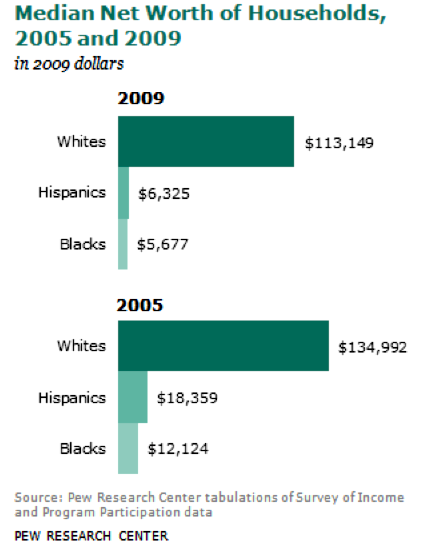

Racial and ethnic inequality has existed since the beginning of the United States. Social scientists have warned that certain conditions have actually worsened for people of color since the 1960s (Hacker, 2003; Massey & Sampson, 2009). Recent evidence of this worsening appeared in a report by the Pew Research Center (2011), as evidenced in Figure 4.3.6. The report focused on racial disparities in wealth, which includes a family’s total assets (income, savings and investments, home equity, etc.) and debts (mortgage, credit cards, etc.). The report found that the wealth gap between white households on the one hand and African American and Latino households on the other hand was much wider than just a few years earlier, thanks to the faltering US economy since 2008 that affected Blacks more severely than whites.

According to the report, whites’ median wealth was ten times greater than Blacks’ median wealth in 2007, a discouraging disparity for anyone who believes in racial equality. By 2009, however, whites’ median wealth had jumped to twenty times greater than Blacks’ median wealth and eighteen times greater than Latinos’ median wealth. White households had a median net worth of about $113,000, while Black and Latino households had a median net worth of only $5,700 and $6,300, respectively (Figure 4.3.6). This racial and ethnic difference is the largest since the government began tracking wealth more than a quarter-century ago.

A large racial/ethnic gap also existed in the percentage of families with negative net worth—that is, those whose debts exceed their assets. One-third of Black and Latino households had negative net worth, compared to only 15 percent of white households. Black and Latino households were thus more than twice as likely as white households to be in debt.

The Hidden Toll of Racial and Ethnic Inequality

An increasing amount of evidence suggests that being Black in a society filled with racial prejudice, discrimination, and inequality takes what has been called a “hidden toll” on the lives of African Americans (Blitstein, 2009). African Americans on the average have worse health than whites and die at younger ages. In fact, every year there are an additional 100,000 African American deaths than would be expected if they lived as long as whites do. Although many reasons probably explain all these disparities, scholars are increasingly concluding that the stress of being Black is a major factor (Geronimus et al., 2010).

In this way of thinking, African Americans are much more likely than whites to be poor, to live in high-crime neighborhoods, and to live in crowded conditions, among many other problems. As this chapter discussed earlier, they are also more likely, whether or not they are poor, to experience racial slights, refusals to be interviewed for jobs, and other forms of discrimination in their everyday lives. All these problems mean that African Americans from their earliest ages grow up with a great deal of stress, far more than what most whites experience. This stress in turn has certain neural and physiological effects, including hypertension (high blood pressure), that impair African Americans’ short-term and long-term health and that ultimately shorten their lives. These effects accumulate over time: Black and white hypertension rates are equal for people in their twenties, but the Black rate becomes much higher by the time people reach their forties and fifties. As a recent news article on evidence of this “hidden toll” summarized this process, “The long-term stress of living in a white-dominated society ‘weathers’ Blacks, making them age faster than their white counterparts” (Blitstein, 2009, p. 48).

Although there is less research on other people of color, many Latinos and Native Americans also experience the various sources of stress that African Americans experience. To the extent this is true, racial and ethnic inequality also takes a hidden toll on members of these two groups. They, too, experience racial slights, live under disadvantaged conditions, and face other problems that result in high levels of stress and shorten their life spans.

Thinking Sociologically

- If you have ever experienced individual discrimination, either as the person committing it or as the person affected by it, briefly describe what happened. How do you now feel when you reflect on this incident?

- Do you think institutional discrimination occurs because people are purposely acting in a racially discriminatory manner? Why or why not?

- Which of the three explanations of racial and ethnic inequality makes the most sense to you? Why?

- Why should a belief in the biological inferiority of people of color be considered racist?

Key Takeaways

- People who practice racial or ethnic discrimination are usually also prejudiced, but not always. Some people practice discrimination without being prejudiced, and some may not practice discrimination even though they are prejudiced.

- Although a belief in biological inferiority used to be an explanation for racial and ethnic inequality, this belief is now considered racist.

- Cultural explanations attribute racial and ethnic inequality to certain cultural deficiencies among people of color.

- Structural explanations attribute racial and ethnic inequality to problems in the larger society, including discriminatory practices and lack of opportunity.

- Individual discrimination is common and can involve various kinds of racial slights. Much individual discrimination occurs in the workplace.

- Institutional discrimination often stems from prejudice, but institutions can also practice racial and ethnic discrimination when they engage in practices that seem to be racially neutral but in fact have a discriminatory effect.

Contributors and Attributions

- Johnson, Shaheen. (Long Beach City College)

- Rodriguez, Lisette. (Long Beach City College)

- Social Problems: Continuity and Change v.1.0 (saylordotorg) (CC BY-NC-SA)

Works Cited

- Anderson, E. (1999). Code of the Street: Decency, Violence, and the Moral Life of the Inner City. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Appier, J. (1998). Policing women: The Sexual Politics of Law Enforcement and the LAPD. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Blitstein, R. (2009). Weathering the storm. Miller-McCune, 2(July–August), 48–57.

- Blank, E.C., Venkatachalam, P., McNeil, L., & Green, R.D. (2005). Racial discrimination in mortgage lending in Washington, DC: A mixed methods approach. The Review of Black Political Economy, 33(2), 9–30.

- Bonilla-Silva, E. (2009). Racism Without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America. 3rd ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Chou, R.S. & Feagin, J.R. (2008). The Myth of the Model Minority: Asian Americans Facing Racism. NY: Routledge.

- Ezeala-Harrison, F., Glover, G.B., & Shaw-Jackson, J. (2008). Housing loan patterns toward minority borrowers in Mississippi: Analysis of some micro data evidence of redlining. The Review of Black Political Economy, 35(1), 43–54.

- Feagin, J.R. (1991). The continuing significance of race: AntiBlack discrimination in public places. American Sociological Review, 56, 101–116.

- Feagin, J.R. (2006). Systemic Racism: A Theory of Oppression. London, UK: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Geronimus, A.T. , Hicken M.T., Pearson J.A., Seashols S.J., Brown K.L., & Cruz T.D. (2010). Do us Black women experience stress-related accelerated biological aging?: A novel theory and first population-based test of black-white differences in Telomere Length. Human Nature, 21(1):19–38.

- Gould, S.J. (1994). Curveball. The New Yorker, pp. 139–149.

- Hacker, A (2003 [1992]). Two Nations: Black & White, Separate, Hostile, Unequal. New York, NY: Scribner.

- Herrnstein, R.J. & Murray, C. (1996).The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Hirsh, C.E., & Cha, Y. (2008). Understanding employment discrimination: A multilevel approach. Sociology Compass, 2(6), 1989–2007.

- Holland, J. (2011). Debunking the big lie right-wingers use to justify Black poverty and unemployment. AlterNet.

- Hurh, W.M., & Kim, K.C. (1999). The “success” image of Asian Americans: Its validity, and its practical and theoretical implications. In C. G. Ellison & W. A. Martin (Eds.), Race and ethnic relations in the United States (pp. 115–122). Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury.

- Massey, D.S., & Sampson, R.J. (2009). Moynihan redux: Legacies and lessons. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 621, 6–27.

- Massey, D.S. & Denton, N.A. (1993). American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Merton, R.K. (1949). Discrimination and the American creed. In R.M. MacIver (Ed.), Discrimination and National Welfare (pp. 99–126). New York, NY: Institute for Religious Studies.

- Min, P.G. (Ed.). (2005). Asian Americans: Contemporary Trends and Issues (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Muhammad, K.G. (2007). White may be might, but it’s not always right. The Washington Post, p. B3.

- Murray, C. (1984). Losing Ground: American Social Policy, 1950–1980. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Pager, D. (2003). The mark of a criminal record. American Journal of Sociology, 108, 937–975.

- Robeznieks, A. (2020, October 23). Why covid-19 hits Latinx at nearly double overall U.S. rate. American Medical Association.

- Robinson, E. (2012, March 23). Perils of walking while Black. The Washington Post, p. A19.

- Rothstein, R. (2012). Racial segregation continues, and even intensifies. Economic Policy Institute.

- Stoll, M.A. (2008). Race, place, and poverty revisited. In A.C. Lin & D.R. Harris (Eds.), The Colors of Poverty: Why Racial and Ethnic Disparities Persist (pp. 201–231). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Schulman, K.A., et al. (1999). The effect of race and sex on physicians’ recommendations for cardiac catheterization. The New England Journal of Medicine, 340, 618–626.

- Segura, D.A. (1992). Chicanas in white-collar jobs: “You have to prove yourself more.” In C.G. Ellison & W.A. Martin (Eds.), Race and Ethnic Relations in the United States: Readings for the 21st Century (pp. 79–88). Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury.

- Smedley, B.D., Stith, A.Y., & Nelson, A.R. (2003). Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Stoll, M.A. (2008). Race, place, and poverty revisited. In A.C. Lin & D.R. Harris (Eds.), The colors of poverty: Why racial and ethnic disparities persist (pp. 201–231). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Turner, M.A. (2002). All Other Things Being Equal: A Paired Testing Study of Mortgage Lending Institutions. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2019, August 22). Profile: Latino/Hispanic Americans.