5.4: Social Institutions

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 104059

- Erika Gutierrez, Janét Hund, Shaheen Johnson, Carlos Ramos, Lisette Rodriguez, & Joy Tsuhako

- Long Beach City College, Cerritos College, & Saddleback College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Government/Politics

The contentious tone between the United States government and Indigenous peoples was set when in 1824, President James Monroe expedited "the handling of the affairs of the tribes and with the concept of protecting them...initiated the the formation of a fiscal bureau in the War Department called the BIA (Bureau of Indian Affairs) (Coffer, 1979)." The BIA was eventually moved to the Department of Interior, but it was clear that the government was expecting to manage AI/AN folks in a hostile and paternalistic fashion. The next few examples will demonstrate the ongoing tension and partial resolutions between the U. S. government and Native Americans.

Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA)

This government placed the running of Native American reservations upon this federal agency rather than tribal elders. This included control over reservation budgets, schools, and even tribal membership (Healey & O'Brien, 2015). Eventually, the power of the BIA diminished, but it had long standing paternalistic effects upon American Indians.

1851 Indian Appropriations Act

According to Elliott (2015),

the Indian Appropriations Act of 1851 authorized the creation of Indian areas in what is now Oklahoma. Native peoples were again forced to move to even smaller parcels of land now called reservations. The U.S. government had promised to support the relocated tribal members with food and other supplies, but their commitments often went unfulfilled, and the Native Americans’ ability to hunt, fish and gather food was severely restricted.

This act further promoted and supported settler-colonialism.

1862 Homestead Act

This Act allowed for any qualified citizen (at the time, it was primarily white Americans) to claim land for settlement purposes. The land that was being "claimed" was taken/stolen from American Indians (Acuña, 2015).

1871 Indian Appropriations Act

This Act removed the status of American Indian tribes as sovereign nations, which meant that Native Americans were now wards of the state. By taking away their independent nation status, the result was full paternalism in which the United States was "parenting" Native Americans for their "own good" (Healey & O'Brien, 2015).

1885 Major Crimes Act

This Act allowed for the United States to defy and/or nullify any treaty with Native American Nations regarding autonomous jurisdiction in tribal lands. In other words, should an American Indian commit certain types of crimes on tribal lands, the United States could violate the sovereignty of these lands to attempt to capture said "criminal" rather than that "criminal" being dealt with by that particular American Indian nation (Aguirre & Turner, 2004).

1924 Indian Citizenship Act

Despite being the original inhabitants of the United States, Native Americans were one of the last racial groups to be conferred U. S. citizenship. The 1924 Indian Citizenship Act provided U. S. citizenship to any Native American person born within U. S. territories. It has been argued that the intent of this act was to reduce the demand for Indigenous identity among American Indians. Tribal nations such as the Hopi and Onondaga rejected this Act by providing their own tribal passports (Aguirre &Turner, 2004).

1934 Indian Reorganization Act

This Act attempted to provide more autonomy to Native Americans by rescinding the Dawes Act and allowing tribes to adopt their own constitution and elect their own tribal council. Although the goal was for more self-governance, the expectation was for tribes to conform to the values and practices of dominant (white) society. Moreover, having one tribal leader to represent an entire reservation could manifest intragroup conflict since a reservation could be made up of different American Indian tribes (Healey & O'Brien, 2015; Schaefer, 2015).

1946 Indian Claims Commission Act

In an effort to provide legal recourse to American Indians, this Act established a Claims Commission that would hear cases brought about by Native Americans regarding the loss of their lands. Unfortunately, this commission did not have the authority to return lands, but rather financially compensated American Indians for those lands. This financial compensation would not result in much money or cover the true value of these stolen lands (Aguirre & Turner, 2004).

1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act

In this act signed by President Richard Nixon, the sovereign status of American Indian nations in Alaska was revoked, which basically made an estimated 44 million acres of formerly Native American lands the property of the United States (Aguirre & Turner, 2004). As of 50 years ago, the U. S. was still appropriating millions of acres of American Indian lands.

1990 National Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA)

Enacted in 1990, NAGPRA

describes the rights of Native American lineal descendants, Indian tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations with respect to the treatment, repatriation, and disposition of Native American human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony, referred to collectively in the statute as cultural items, with which they can show a relationship of lineal descent or cultural affiliation (McManamon, 2000).

Museums like the Smithsonian, have a dedicated Repatriation Office tasked with fulfilling the parameters of both the 1989 National Museum of the American Indian Act (NMAI), as well as NAGRPA. In 2017, the remains of 24 Alaska Natives from the village of Igiugig (Alaskan Yupik) were repatriated over 80 years after they were taken (Daley, 2017). Although NAGPRA has made repatriation efforts more accessible, these efforts are not equitable. According to Rebecca Kitchens (2012), current laws, including NAGPRA, grant some Nations legal access to their cultural objects at the expense of other Nations or Indigenous peoples, ultimately a hierarchy legally favoring some over others.

Like repatriation efforts, it is also important to bring attention to the trust status of tribes which guarantees their lands to be returned to them. In a notable example, the state of Alaska was suing the federal government arguing that trust status conflicts with the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act. That legal interpretation meant Alaska Natives were banned from putting lands into trust until recently (Estus, 2016). The State of Alaska eventually dropped its lawsuit, but this legal battle represents one of the many challenges for AI/AN people to establish and/or maintain trust status.

Education

Historically, American Indian children did not have much of a choice with regards to their education since the U. S. government, through the BIA, intentionally sent children far away from their families to Native American boarding schools, discussed in Chapter 5.2. The purpose of these boarding schools was to coercively assimilate Native American children which meant that they could only speak English and convert to Christianity. It was forbidden for them to use tribal languages, dress, religion, and any other Native cultural element. Mary Crow Dog describes the boarding schools as "run like a penal colony" (Dog, 1990).

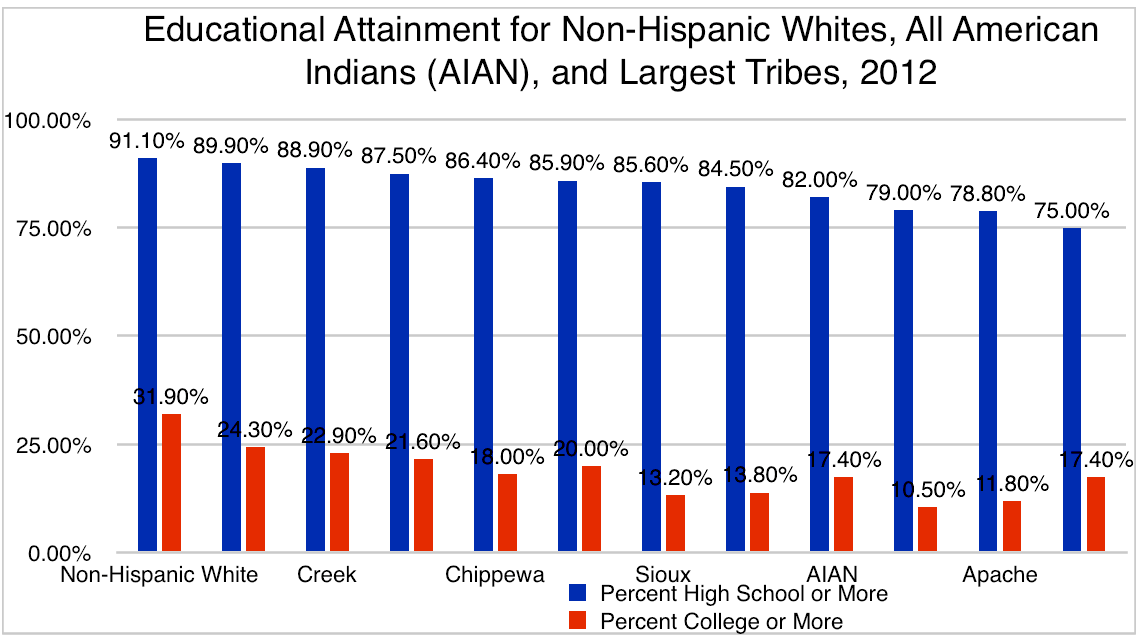

Native American boarding schools were mostly all closed by the 1970s, but they left an indelible impact on the educational attainment of American Indians up to the present. The 2012 educational attainment data from the U. S. Census indicates that American Indians were very likely to attend high school, but college attendance and/or completion was not likely as shown in Figure 5.4.4. Once the model of American Indian education shifted from coercively assimilating them to having tribally controlled colleges, there was an increased shift in their educational attainment, but not yet to the levels of non-Hispanic whites.

The 1975 Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act provided Native American Nations much more autonomy with setting their own administrative and governing structures absent of BIA interference, as well as, gave them the tools and resources to address and improve their situations (Healey & O'Brien, 2015). Specifically, this Act significantly impacted AI/AN education because it helped pave the way for tribal colleges to be controlled by Indigenous peoples not the government or the BIA. Now deceased Indigenous leader Wilma Mankiller's words echo in this change: Whoever controls the education of our children controls the future.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Educational Attainment for American Indians. The overwhelming majority of all groups have a high school diploma or more, the rates for all AI/AN groups are lower than their non-Hispanic and white counterparts. While approximately 32% of non-Hispanics were college educated in 2012, a lesser percentage of all AI/AN groups were college educated. (Data from the U.S. Census (2013); Healey & O'Brien (2015))

Family

The following categories can be used to understand kinship:

- Matrilineal—kin relationships are traced through the mother, children belong to the kin group of their mother.

- Patrilineal—kin relationships are traced through the father, children belong to the kin group of their father.

- Bilineal (bilateral)—kin relationships are traced through both the father’s and mother’s kin groups.

These categories may seem relatively simple, but they can have strong impacts on other aspects of society. And are they so simple? How would you categorize the dominant kin groups of the United States and Canada? Bilineal? If so, why do most of us have the last names of our fathers, as in patrilineal societies? Further, in a patrilineal or matrilineal society the incest taboo is applied differently to the mother’s or father’s side of the family. So whether a society is matrilineal or patrilineal can determine with whom you can have sex and marry and who you cannot.

Societies are also understood by social scientists as being either endogamous or exogamous. In an exogamous society people typically (in some instances must) marry someone from outside of their group or locality (where they live, their village or town). In an endogamous society people typically marry someone from their community. Cross cousin marriage are typically found in endogamous societies and the practice helps to increase the relationships between families, which encourages those related families to work with each other in getting resources. In an exogamous society, individuals and families build relationships with families in other localities. Another kinship organization of society are moieties. In moieties, the kin groups of a particular society are divided into two groups, which may be exogamous. Moieties often function as ceremonial divisions in a society. For example, among the Iroquois, when a member of your kin group dies, the members of a different moiety will plan and conduct the funeral to “help wipe the tears from your eyes.” Among the Tewa, a Puebloan Nation living in the southwestern part of the U.S. moieties function as a very important part of the ritual and ceremonial aspect of the society. Men and women must marry someone from another moiety, and women will be adopted into the moiety of their husbands after they marry (Ortiz, 1969).

Other concepts that help to understand kinship are lineage and clan. In societies that recognized lineages (they are often patrilineal), the members of the lineage can trace their descent from a common ancestor. A clan is harder to define. The members of a clan believe they are related, even if they cannot trace their descent to a common ancestor. Both lineages and clans are exogamous. Lineages are often found in patrilineal societies, clans in matrilineal societies. Many Native American societies recognize clans. While European societies are now generally patrilineal (although, less than a 1,000 years ago the Irish were matrilineal), Native American societies can be matrilineal, patrilineal, or bilineal. Further, these kinship organizations are very flexible and have changed within the last 200 years.

In Tewa society there are two patrilineal clans: Summer and Winter. Ortiz (1969) states that children are not automatically born into those clans, but must go through several rituals of “incorporation.” Women are generally adopted into the clan of their husbands after marriage. Further, children may be adopted into the other clan, even after being incorporated into a clan. Ortiz (1969) gives an example of a man who had only daughters. When they married, they were adopted into the clan of their husbands. The father then adopted a son of his oldest daughter into his clan. Medicine people and healers would also adopt apprentices who were not of their clan into their clan. All these adoptions involved rituals of incorporation (Ortiz, 1969).

The Iroquois (Haundenosaune) society is a group of Native Americans linked by language, political organization, and kin groups. They have and continue to occupy the area of what are now northern New York and southern Quebec and Ontario for around 2,000 years. The Iroquois are a matrilineal society in which the consanguine kin groups are organized into clans: Bear, Wolf, Deer, Hawk, Snipe, Heron, Turtle, Beaver and Eel. The Iroquois don’t believe they are descended from these animals, but in the ancient times of oral tradition, the relationship between animals and people was so close they could even communicate with each other. As in the story about Sky Woman, the Turtle provided a place for her to land and on which the Earth now resides. The women of the Bear clan learned about medicinal plants from a shape-changing bear.

The Navajo (Dine) are also considered to be a matrilineal society. Unlike the Iroquois, a Navajo would say they is born to the clan of their mother and for the clan of their father. Further, the Dine recognize their relatedness to their maternal and paternal grandfathers’ clans. The Navajo are considered matrilineal because the inheritance of usufruct rights (the rights of individuals to use land or other resources) transfers from mother to daughters.

The Inuit of the Arctic are an example of a bilateral society. Kinship is equally traced through both the mother’s and the father’s side. The Inuit live in a challenging natural environment. Their kinship organization may be because the people of this society must depend on one another for survival. The more people you can call on for help, the more likely you (and they) will survive. Bilateral societies are typically foragers, traveling from area to area to get needed resources. They may have been mobile and bilateral for centuries, like the Inuit. Others, like the Cheyenne and Sioux, may have became bilateral after changes in economic and settlement patterns caused by Euro American intrusions into their territory resulting in them morphing from settled, horticultural societies to foraging societies. Bilateral kinship organization was more adaptive to the mobility of foragers and increased kin networks.

Religion and Spiritual Beliefs

The origin stories of Indigenous peoples throughout North America are also quite different from each other. Each Native American society has its own origin story; there is no one story as there is in Christianity and Judaism. Origin stories are just one aspect of religious or spiritual beliefs for any society.

In many Indigenous origin stories, animals, plants, and even forces of nature like the snakes that ate the disrespectful young man, are active participants in the story. Unlike the Judeo-Christian story in which the serpent is the only animal to have a part mentioned, in Native American stories the animals are very important to the action of the story; often they help humans to survive. Animals may sometimes be tricksters, like Coyote of southwestern stories or the Great Hare of the Southeast, but even they sometimes help humans. You may notice from many of the stories mentioned, humans and animals cooperate and work together. Many Native American societies believe that all things in the world have souls or spirits: therefore all things in the world must be treated respectfully. Social scientists call this animism, the belief that key parts of nature have spirits. In foraging societies there are thanksgiving rituals for the animals that give their lives for us to eat. Failing to enact the rituals may result in the animals withdrawing themselves. For all living things there are expectations of behavior, and when humans or animals do not meet these expectations, there are consequences.

Ceremonies and rituals are another important part of any religious tradition. Among many Native American societies there are rituals or ceremonies that re-enact aspects of origin stories. Among the Hidatsa, Sioux in North Dakota, this ceremony is called the Naxpike or hide beating, and has many of the elements common to the Sun Dance practiced by societies throughout the Plains' Nations. The ceremonial grounds where the ritual will take place are prepared and blessed by the elder women, then a post made from a cottonwood tree is placed in the middle of the grounds by the elder men. Young men volunteer to re-enact the suffering and torture of Spring Boy, the first to person to do the Naxpike. By doing so they achieve individual visions and help renew the earth for their community (Bonvillain, 2001). As with origin stories, rituals and ceremonies vary from society to society.

Rituals and ceremonies can meet the needs of individuals and the community. For instance, horticultural or agricultural societies have ceremonies or rituals to ensure the growth of their crops. Among the Haundenosaune of the Iroqouis Nation in the Northeastern U.S., there are ceremonies for the coming of maple sap and strawberries. There are several for corn: the planting of the seeds, the “greening of the corn,” when the plant “tassels,” and the harvesting of the crop. Many societies also have rituals that renew the earth itself, such as the Hidatsa’s Naxpike or the Sun Dance practiced by many Plains societies. The Naxpike or Sun Dance may be done to fulfill an individual’s vow or to invoke a vision. These rituals also fulfill community needs, bringing the community together and renewing the earth for the upcoming year.

In addition to offering thanks, these ceremonies were and are also an opportunity for the community to come together, iron out grievances, have a good time, and look for potential marriage partners. Modern-day pow-wows function in a similar way for contemporary Native American communities. While the traditional ceremonies are still practiced by many societies, pow-wows are an opportunity for those who no longer live on the reservation or reserve to come home to celebrate their culture and family connections. Pow-wows are used to honor respected members of the community, and currently are often held to welcome returning war veterans and incorporate them back into the community. These gatherings are an example of how rituals function on a societal level, bringing the community together for mutual purposes and benefits.

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): The Grand Portage Pow Wow, held annually in Minnesota. Image shows Indigenous dancers and veterans. (CC BY-SA 3.0, Wpwatchdog via Wikimedia)

Among the most specialized of spiritual roles is that of a shaman. The word “shaman” is Siberian in origin and refers to a man or woman who is able to travel to the spirit world through a trance state. In traditional Native American societies, all people have some access to spiritual power and knowledge. Shamans typically work for the entire community to find out why the crops have failed or why hunting has been unsuccessful. In many Arctic societies, it is believed that the animals they depend on were made from the fingers of a woman named Sedna, the guardian of the animals. Sedna will withdraw or remove the animals if hunters have not treated them respectfully and done the thanksgiving rituals after killing them. If hunting becomes unsuccessful, the community’s shaman will enter a trance state and travel underwater to where Sedna lives to find out why the animals have been withdrawn and what must be done to bring them back. To appease Sedna, the shaman will comb her hair, which she can no longer do because of the loss of her fingers.

Shamans and trances are part of the spiritual traditions of many societies around the world. In some societies, anyone may attain a trance through dancing, drumming, chanting, or the use of hallucinate drugs, but they are not recognized as shamans because their trances are typically for individual purposes, while a shaman typically goes into a trance state to benefit his/her community. Shamans are usually called to what can be very difficult roles in their society. An individual may be called through dreams. In many Native American societies, people who have nearly died, particularly through an illness, are thought to have the power to become a shaman because they have already traveled to the spirit world and returned. Among the societies of the Northwest coast, individuals might spend their lifetimes training to become a shaman, often apprenticing themselves to a shaman and inheriting their teacher’s powers upon their death.

While shamans have special spiritual powers, Native American societies believe all people—indeed, all living things—have access to spiritual power. One of the ways spiritual power is attained is through dreams. Revitalization movements were often started in response to dreams. Dreams are seen as a conduit between people and the spirit realm. Through dreams the spirits tell people how to live their lives, what they’re doing wrong, even warning them of danger. Many Native American societies have rituals in which people seek advice about their dreams. A person with a troubling dream may go to a shaman; or, as among the Haundenosaune (Iroqouis), they may tell it to the entire community for advice about its meaning. The Iroquois, and many other Native American societies, believe the messages of dreams must be acted upon or there will be negative consequences for the individual and the entire community.

Another way individuals have access to spiritual power is through visions. Men and women will undertake a vision quest as a way to attain spiritual power. In a vision quest individuals will go to a solitary place and go without food, water, and sleep in order to obtain a vision. It is believed the spirits will tell individuals what is expected from them through visions.

The vision quest can be part of life cycle rituals—rituals that mark important transitions in a person’s life. Not all Native American societies have the same life cycle rituals, but there are typically rituals to mark birth, the attainment of personhood, adulthood, marriage, and death. A mother (and sometimes the father) may begin rituals before a child is born. A mother may abstain from some foods, such as rabbit, to ensure the child will be brave and not run away from danger. Rituals are done to ensure an easy delivery and a healthy child. Among the Dine, a blessingway song is sung over the mother to ensure an easy birth and protect the child and mother from evil spirits. The mother may also be given medicinals, and the women in her family may manipulate her abdomen to aid in the birth. After birth and bathing, the baby is sprinkled with white and yellow corn pollen, and the women of the mother’s family will gently press the baby’s body to ensure good health.

It is a sad fact that not all children who are born survive. Factors like malnutrition, diseases, and poor water supplies can all affect the survival rates of infants. In non-industrial societies, infants who die are generally not given their society’s typical burial rituals. Many societies believed the infant’s soul enters the body of another newborn, went into an animal or bird, or returned to the spirit world until it could be born again. So while ceremonies may be done at birth, a child is often not considered a person or given a name until she or he has lived for a time. Such rituals are personhood rituals, as they incorporate the child into his or her society. Among the Tewa Pueblo Nation, for example, children are incorporated into their moiety and given a moiety-specific name during the water-giving ritual when they are eight days old. The Zunis believe a newborn child is soft or not yet ripened, so it is kept in the house away from the sun for eight days after birth. Before dawn on the eighth day the child’s umbilical cord is buried, connecting the child to Mother Earth and the underworld from which its ancestors emerged. The baby is washed, put in its cradleboard, and cornmeal is put in its hands. Its paternal grandmother will carry the baby outside, facing the rising sun. The baby usually does not receive a name then. The family will wait until the baby has hardened (gotten older) and are confident the child will survive (Bonvillain, 2001).

Among the most important rituals for any individual are coming of age rituals. Coming of age rituals mark the transition from childhood to adulthood. The vision quest is an example of a coming of age ritual for young men. Often, for the first time, they must go into the woods, mountains, or desert by themselves, fast, and try to stay awake until they receive a vision. Killing an animal for food or fighting an enemy may also be part of a young man’s coming of age ritual. The young man’s family will hold a feast and often give-aways, in which goods and resources are given away, to mark his transition to adulthood.

Young women also go through coming of age rituals, usually when they start menstruating. Among the most elaborate is the kinaalda, girl’s puberty rite, of the Dine. The kinaalda is a four-day ceremony. At dawn and noon on each day, the young woman, accompanied by friends and family members, races to the east to build up her strength and endurance. A respected older woman will knead her body (as newborn babies are kneaded) to mold her to also become a respected woman. The young woman and her family prepare large amounts of food, particularly corn, to be part of a community feast held on the fourth day. On this day the young woman washes, and then her face is painted with white lines. She then distributes food to all the guests (Schwarz, 1997).

Historically, Native American marriage ceremonies were not as elaborate as those of contemporary U.S. and Canadian societies. The ceremony would often consist of the exchange of gifts between the bride and groom and their families and a feast. Of more importance were death or funeral rituals. Like birth and adulthood, death is a transition, so anthropologists often call rituals that mark them rites of passage. For many Native American societies, birth is the transition from the spirit world; death is a transition back to the spirit world. Death rituals may be started before the individual dies to help in this transition. Among the Dine’, for example, a night way ceremony may be held to help prepare the individual and his/her family for the death. The Dine’ have a great fear of ghosts; so, much of the behavior at the funeral ritual is to ensure the ghost of the dead does not stay around kin members. The body is carefully washed and dressed by kin members, but the left moccasin is put on the right foot and the right moccasin is put on the left foot, to make it difficult for the ghost to walk. If the person dies at home, the body is carried out through a hole cut into the wall so as to not contaminate the usual paths of the living. If the deceased dies in a hogan, the traditional house-structure of the Dine, the hogan is abandoned or burnt down. The body is transported in silence to a remote spot. Burial typically takes place in the ground, or a rock niche that is then sealed. The mourners return by a different path, go through a purification ceremony, and never speak the name of the deceased. These observances help to ensure that the ghost of the deceased does not follow or return to haunt family members (Bonvillain, 2001). The Dine believe the deceased must become part of nature or the cosmos, “as a drop of water is part of a rain cloud.”

Mass Media

The sports world abounds with team names like the Indians, the Warriors, the Braves, and even the Savages and Redskins. These names arise from historically prejudiced views of Native Americans as fierce, brave, and strong savages: attributes that would be beneficial to a sports team, but are not necessarily beneficial to people in the United States who should be seen as more than just fierce savages.

Since the civil rights movement of the 1960s, the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) has been campaigning against the use of such mascots, asserting that the “warrior savage myth . . . reinforces the racist view that Indians are uncivilized and uneducated and it has been used to justify policies of forced assimilation and destruction of Indian culture” (NCAI Resolution #TUL-05-087 2005). The campaign has met with only limited success. While some teams have changed their names, hundreds of professional, college, and K–12 school teams still have names derived from this stereotype (Chapter 4.2). Another group, American Indian Cultural Support (AICS), is especially concerned with the use of such names at K–12 schools, influencing children when they should be gaining a fuller and more realistic understanding of Native Americans than such stereotypes supply. What do you think about such names? Should they be allowed or banned? What argument would a symbolic interactionist make on this topic?

In 2020, amidst the Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd, the Washington Redskins retired their mascot. The Washington Football Team has since followed suit (Rathborn, 2020). Finally, the 2018 NCAI Resolution for National Football League (NFL) teams to discontinue promoting institutional racism and disparaging and diminishing terminology has been realized.

Video \(\PageIndex{9}\): "Proud to Be (Mascots)" video produced by the National Congress of American Indians with intention to be aired during Superbowl coverage in 2014. (Close-captioning and other YouTube settings will appear once the video starts.) (Fair Use: National Congress of American Indians via YouTube)

On a final note, there have been some incredible documentaries regarding Indigenous peoples created by and/or from a Native perspective. On the topic of mascots, More Than a Word and In Whose Honor? are remarkable documentaries. Powwows.com and Indian Country Today are contemporary Indigenous media sources.

Contributors and Attributions

- Gutierrez, Erika. (Santiago Canyon College)

- Hund, Janét. (Long Beach City College)

- Minority Studies (Dunn) (CC BY 4.0)

- Introduction to Sociology 2e (OpenStax) (CC BY 4.0)

- Native Peoples of North America (Stebbins) (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Works Cited

- Acuña, R.F. (2015). Occupied America: A history of Chicanos. 8th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Aguirre, A., Jr. & Turner, J.H. (2004). American Ethnicity: The Dynamic and Consequences of Discrimination. 4th ed. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

- Bonvillain, N. (2001). Native Nations: Cultures and Histories of Native North America. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Brown, D. (1970). Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- Coffer, W.E. (1979). Phoenix: The Decline and Rebirth of the Indian People. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company.

- Dog, M.C. & Erdoes , R. (1990). Lakota Woman. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

- Elliott, S.K. (2015). How American Indian Reservations Came to Be. Public Broadcasting Service.

- Estus, J. (2016). Alaska drops appeal of tribal land into trust regulation. KTOO Public Media.

- Healey, J.F. & O'Brien, E. (2015). Race, Ethnicity, Gender and Class: The Sociology of Group Conflict and Change. 7th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Kitchens, R. (2012). Insiders and outsiders: The case for Alaska reclaiming its cultural property. Alaska Law Review 29(1), 113-147.

- McManamon, F. (2000). The Native American graves protection and repatriation act (nagpra). In L. Ellis (Ed), Archeological Method and Theory: An Encyclopedia. New York, NY and London, UK: Garland Publishing Co.

- National Congress of American Indians. (2005). The National Congress of American Indians Resolution #tul-05-087: Support for NCAA Ban on ‘Indian’ Mascots.

- Ortiz, A. (1969). The Tewa World: Space, Time and Becoming in a Pueblo Society. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Rathborn, J. (2020). Washington redskins confirm new name. The Independent.

- Schaefer, R.T. (2015). Racial and Ethnic groups. 14th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Schwarz, M.T. (1997). Molded in the Image of Changing Woman: Navajo Views on the Human Body and Personhood. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.