5.2: Strategies for staying in power

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 150446

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Evaluate various institutional strategies by which non-democratic regimes remain in power

- Analyze cultural and ideological explanations for the persistence of non-democratic regimes

Introduction

All regimes possess a variety of means for staying in power. One common heuristic for thinking about these tools is through a simple “carrots versus sticks” breakdown of strategies. Carrots take the form of inducements or benefits that are doled out to gain the loyalty of constituents. Sticks are focused on meting out punishments as negative reinforcement of the rules.

Source: Idioms4U

Governments may also expend resources to shore up their legitimacy in the minds of citizens through sophisticated propaganda bureaucracies or control of information flows to the people. Here the term propaganda is used to refer to biased information communicated to convince audiences of a particular political view. It's purpose is to control people’s perceptions and thoughts, and is especially powerful when it can draw on existing cultural foundations in society.

All regimes utilize a mix of carrots, sticks, and ideas to stay in power. For example, internal investigative bureaucracies, such as the Ministry of State Security in China, have counterparts in democracies, such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in the United States. Similarly, virtually all countries in the world, regardless of regime type, have police for maintaining domestic order. But when compared to democracies, non-democracies are relatively unconstrained in their ability to use force or manipulate information in order to ensure compliance with their rule. The lack of robust accountability mechanisms is a crucial difference in how public institutions are managed and the scope of their authority.

Institutional channels

Regimes are most likely to endure when they build and maintain institutions. (Institutions are shared practices, norms, and organizations which exist beyond any single individual.) Some people think of them as the “rules of the game” for all social life. Institutions structure the way we do things, organize our interactions with others, and are the source of social and political power. For example, take the institution of the state. The state is one of the most powerful institutions in the modern world today. The beliefs and norms surrounding states, which are shared globally, confer great power on states. States manage nuclear arsenals, squeeze taxes from billions of citizens, and manage the global flow of trade and finance.

Because of the power of institutions, regimes have an interest in institutionalizing their rule. Thus, these institutions relate to each other in many ways: they can reinforce each other, be nested in one another, and one institution can beget another. Regimes are institutions unto themselves. By absorbing and dispersing resources, regimes stay in power.

POSITIVE INDUCEMENTS (aka the carrots)

Let’s start with institutional carrots. Nondemocracies have in place a variety of institutions that provide positive inducements for supporting the regime: institutions for co-opting opposition, patronage networks, and clientelism. Each of these is distinct but can overlap with the others.

Institutions for co-opting opposition

All non-democracies face the problem of being ousted from power. To blunt the force of an opposition, or even vocal critics, a regime might invest in institutions that have the appearance of democratic representation, such as rigged elections, legislatures, courts, etc. These institutions are actually “window dressing” or façades for a tightly controlled political system. In these systems, judiciaries are not independent, nor do they provide a meaningful check on the authority of rulers. Many non-democratic regimes have in place legislatures that lack the authority to veto measures passed by those in power. An example is the highly authoritarian Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), or North Korea. The country has been ruled since the 1950s by a single Supreme Leader, yet formally it has a unicameral legislature. This Supreme People’s Assembly comprises nearly 700 deputies; and in theory, confers authority on the Supreme Leader. However, DPRK’s Supreme Leader makes all governance decisions for the country and does not face any threat of veto by this unicameral legislature.

Opposition parties or critics of the regime might agree to sit on such bodies as a means to have access to and possibly influence political leaders. They may also benefit materially from legislative or judicial seats, such as drawing a salary or receiving other perks of office like having a chauffeured car or swanky office. Co-opting opposition through such institutions can boost the legitimacy of the rulers in the eyes of the public. They also allow rulers to more closely monitor the positions and ideas of opposition, which might then be countered or even adopted as appropriate.

Patronage networks

All politics hinge on relationships and the flow of resources. Patronage networks are relationships within political systems in which one party distributes resources to those within their network. For example, a leader might take a portion of oil revenues and distribute those monies to their deputies scattered throughout the provinces. Then, those deputies make sure that the leader’s posters are prominently displayed in every local government office. The reciprocal bond unites members of the network.

Patronage networks may be organized via many different kinds of organizations or social groups, such as the military or state-owed businesses. In addition, political parties may distribute public resources in exchange for political obedience. Identity groups, including those bound by ethnicity or tribe, may be the basis of patronage networks. For example, in Syria, major institutions of the state are controlled by the Alawite minority, a Shia Muslim group that is less than one-fifth of the population. Alawite networks support the ruling al-Assad family.

Broad-based clientelism

Although related to patronage networks, institutions promote clientelism on a broad scale. Clients are those who rely on a patron for resources. Thus, clientelism is a strategy whereby rulers seek to buy off the loyalties of broad swaths of the population. To do so, rulers invest in mass social programs to which they have clearly marked their sponsorship. Such broad-based distribution of resources has the effect of turning significant parts of a country’s population into clients, or dependents, of the regime.

Broad-based clientelism was utilized during the rule of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (or Partido Revolucionario Institucional, PRI) in Mexico from 1929 to 2000. Under the PRI presidency of Carlos Salinas de Gortari (1988-1994), social programs were consolidated under a new government organization called Pronasol. This group distributed government funds to poor communities to build public works such as schools, health clinics, water treatment facilities, and electric grids. At its height, there were nearly 250,000 Pronasol committees at the grassroots level to carry out community projects in collaboration with community leaders. The results are impressive: renovations of 130,000 schools, creation of 1,000 rural medical units, and plumbing access for 16 million Mexican residents (Merrill and Miró eds. 1996). Looking back on this ambitious program, it represented a broad-based means to build support for PRI rule throughout the country and especially in the countryside.

REPRESSIVE STRATEGIES (aka the sticks)

Next, let’s turn to institutional sticks, or strategies of repression. There are a variety of repressive means by which nondemocratic regimes extract obedience from the population, including the creation of domestic security bureaucracies and paramilitary groups.

Domestic security apparatuses

Nondemocracies are the creators of the modern secret police. Examples include the creation of the Cheka under Lenin, which evolved into the NKVD – internal secret police – under Stalin, and then into the KGB in Russia. Italy and Germany had similar systems prior to World War II. These types of institutions can serve critical purposes, from collecting intelligence on potential dissent within a country to terrorizing citizens.

China has developed a sophisticated means for surveilling its population. Indeed, since 2010, the ruling Chinese Communist Party has spent more on domestic security than external defense. “Sharp Eyes” (xueliang) is a nonstop video feed of public squares, intersections of major roads, public areas in residential neighborhoods, and transit stations. It also included monitoring of buildings such as the entry points of radio, TV, and newspaper offices. Today, combined with other projects, there are more than 200 million public and private security cameras installed across China.

Paramilitaries

Paramilitaries are another powerful institution of repression. These groups have access to military-grade weapons and training, yet they are not part of the national military. Typically, they are “irregular armed organizations that carry out acts of violence against civilians on behalf of a state,” (Üngör 2020). In addition to being deployed by governments around the world, they have been used to terrorize citizens. For example, death squads carry out extrajudicial murders, usually of political enemies of the state. During the height of the Cold War in the mid-1960s, Indonesian death squads were responsible for the murder of hundreds of thousands of Indonesians believed to have leftist sympathies.

Cultural and ideological controls

Another powerful way to maintain authority is to convince people to believe in the legitimacy of nondemocratic rule. This action can preempt resistance. Thus, nondemocratic leaders invest in creating strong ideational foundations for their rule. Often, these ideas may derive selectively from deeper cultural traditions within a society – including those linked to faith traditions – or from the dissemination of non-democratic ideologies to the masses.

Undemocratic concepts, such as hierarchy and unaccountable authority, are embedded in many cultural traditions. For example, the monarchies of Europe and the empires of the Americas were supported by the idea of the divine right of rulers. Virtually all major religions of the world promote authoritarian and undemocratic systems of governance and social order, from the rigid patriarchy of the Roman Catholic church to the castes of Hinduism. Several East Asian societies – in China, Korea, and Japan, to name a few – have strong Confucian influences. Confucius, a scholar of antiquity, argued that the hierarchical relationship between ruler and ruled helped constitute an orderly society. This supplemented the idea that Chinese emperors possessed the mandate to rule “all under heaven” (tian xia). To this day, Chinese leaders draw from Confucius’ writings to argue for a “harmonious society” in which dissent is culturally frowned upon.

One ongoing debate is whether “persistent authoritarianism” is an inevitable consequence of certain cultural traditions. Undemocratic cultural elements are not necessarily barriers to eventual democratization. Some political scientists argue for the incompatibility of democracy and Islam, or democracy and Confucianism. Yet many modern democracies have emerged out of these anti-democratic cultural traditions. Turkey and Indonesia are examples of Muslim-majority democracies, while Korea and Japan demonstrate that societies with Confucian influences can become robust democracies.

Beyond cultural traditions, certain powerful political ideologies support nondemocratic rule. Countries organized according to these ideologies have been uniformly undemocratic and lack mechanisms of accountability between ruler and ruled in addition to basic freedoms for citizens.

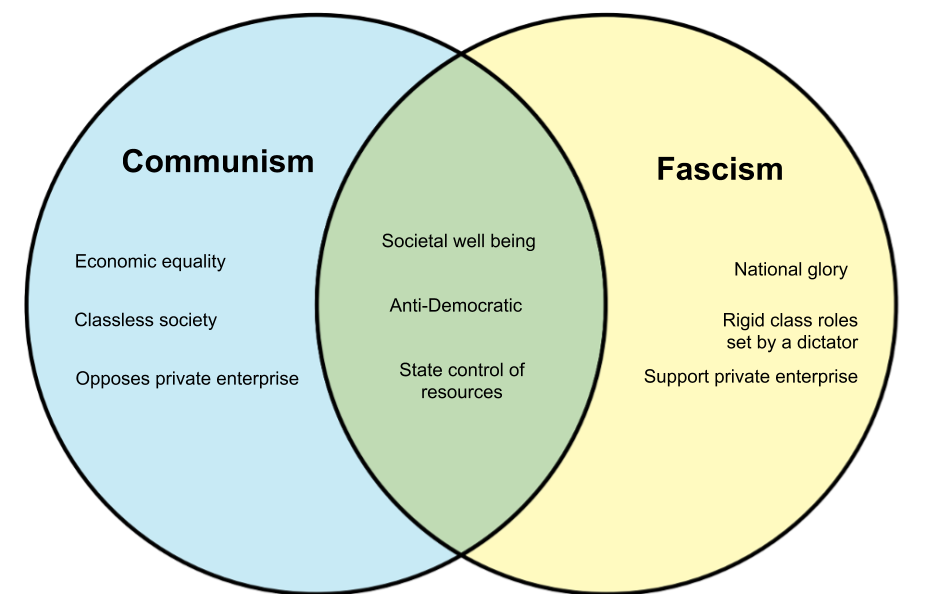

- Communist countries have been led by a “dictatorship of the proletariat” in the process of dismantling capitalism and building the socialist society that is meant to precede the transition to communism.

- Fascist countries are characterized by extreme social hierarchies and control of all aspects of society by the ruling party.

A more narrow tool employed by non-democratic leaders to remain in power is the creation of a cult of personality, where a state leverages all aspects of a leader’s real and exaggerated traits to solidify the leader’s power. A cult of personality creates the illusion of mass support for – even adulation of – the ruler through propaganda bureaus and state control of media channels. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin was famous for creating such a cult around his personal rule. Later leaders built on this idea, such as China’s Mao Zedong and Romania’s Nicolae Ceaușescu. Fanning a cult of personality creates an emotional link between citizens and the ruler, as well as an appearance of invincibility on the part of the ruler, which can serve to stave off challenges to their rule.