Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify different kinds of non-democratic regimes

- Recognize examples of different non-democracies in the world, past and present

Introduction

There is a wide diversity of regimes that are commonly labeled ‘non-democracy’. Typologies offer a powerful means for thinking analytically about a group, by dividing it into subgroups based on certain criteria.

A typology of non-democracies

Creating a typology is an important descriptive exercise. It helps to establish the “lay of the land” and distinguish key characteristics of items within a category. After dividing non-democracies into types A, B, C, and D, a researcher can then ask deeper questions such as: Which type of non-democracy lasts longer, on average? Which type tends to fall into conflict or remain at peace for longer stretches of time? Which enjoys more economic stability? Do types tend to cluster in certain regions of the world?

Typologies of non-democracies are an example of a nominal measure of regime type. That is, the items are not ranked, or ordinal, in relationship to one another. Rather, the typology represents non-democracies divided into sub-groups based on certain characteristics. There is not hierarchy between groups.

Since most things in the social world are dynamic, a typology may work for a certain period of time but then fail to capture changes such as the emergence of a new type or the expiration of old types. In the 20th century, the rise of modern fascist and communist regimes prompted some scholars to argue that a new type of non-democracy, totalitarianism, had arisen. To this day, political scientists debate whether totalitarianism is a useful term.

Another challenge to typology is that some observations may not slot neatly into the types offered, but rather combine characteristics of two or even more types. This kind of combination is observable in the real world, and highlights how types within our typology of non-democracies are not mutually exclusive. In other words, one country may fit several types or change types over time.

In short, typologies are grounded in certain underlying characteristics that divide a group into subgroups. They are dynamic and can shift with changes in those underlying characteristics of the category being observed. New types of non-democracies are identified over time, which may eventually become widely accepted by specialists and more casual observers. Illiberal or hybrid regimes, which will be discussed later, is one example of this phenomenon.

There are many typologies for dividing up the countries classified as non-democracies in the world. This chart (see below) depends on two qualitative factors

- Leadership focuses on questions such as whether the core leadership comprises one or several people. Other leadership characteristics may answer: Are civilians or the military in power? Do the leaders all come from a certain institution, such as a political party or religious group?

- Foundations of regime authority is also important. What are the animating ideas that lend legitimacy to the regime? Is the regime guided by a religion or a particular ideology?

When considering these two sets of factors, we can focus on five major types of non-democracy in the world today. Table 5.3.1 summarizes these types.

Table 5.3.1: Types of non-democracies based on leadership characteristics and sources of legitimacy

| Type of non-democracy |

Leadership characteristics |

Sources of legitimacy |

| Theocracy |

Single leader or collective rule |

Religious texts |

| Personalist or monarchy |

Single leader |

Variable: Religion, charisma, tradition |

| Single-party rule or oligarchy |

Collective rule |

Variable: Religion, political ideology such as communism, fascism |

| Military rule |

Variable: Single leader or collective rule, all military |

Variable: Religion, political ideology, beliefs about military competence |

| Illiberal regime |

Variable |

Variable, but all have a veneer of liberal democracy |

Theocracy

Theocracies are as old as organized religion. Many theocracies are non-democracies in which the authority of political leaders is grounded in a sacred text. These texts, in turn, provide divine legitimacy to political leaders, who are not accountable to the public. Political institutions are organized in accordance with prescriptions in a sacred text, notably executive office, the legal code, legal system, and schools. Some current non-democratic theocracies are those organized around Islam, such as Saudi Arabia and Iran. Meanwhile, the Vatican is organized around Roman Catholicism.

Personalist rule and monarchy

Non-democracies characterized by personalist rule are led by a single leader. Legitimacy derives from a variety of sources, such as personal charisma or their ability to serve as a convincing interpreter of a political ideology for all of society. An example of the former is Idi Amin of Uganda (r. 1971-1979), and an example of the latter is Fidel Castro of Cuba (r. 1959-2008). Some personalist leaders come to power through family dynasties, such as the al-Assad family in Syria. In all of these cases, personalist leaders are not subject to formal mechanisms of accountability.

Personalist rule is often combined with other types of non-democracy. A charismatic leader may rely upon the organizational heft of a ruling party or the military to remain in power. Idi Amin was a commander in the Ugandan army. Fidel Castro commanded the formidable organizational apparatus of the Communist Party of Cuba and Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces.

Overall, personalist rule tends to be unstable due to problems of succession. There may be hesitant to designate a successor because that successor then has incentives to depose the ruler from power. But if a successor is not designated, then instability is likely to set in upon the ruler’s death.

A monarchy is similar to personalist rule in that there is a single leader, but the bases of legitimacy tend to be grounded in tradition or sacred texts. The Vatican City is a theocracy, as well as a self-described “absolute monarchy” because it is led by a pope. The Kingdom of Bahrain is an example of a constitutional monarchy and has been led by the Al-Khalifa family since 1783.

Single-party rule and oligarchy

In contrast to personalist rule, single-party rule and oligarchies are shaped by collective leadership. In an oligarchy, elites control political office and national resources, and are not accountable to the public for their actions. One of the earliest examples was the ancient Roman Republic, where only the very wealthy could hold high political office.

Political scientist Jeffrey Winters (Winters 2011) has theorized that there are two key dimensions to oligarchies.

- First, the wealth of oligarchs is difficult to seize and disperse.

- Second, their power extends systemically, across the entire regime. In the contemporary world, Russia has been subject to a great deal of political influence by oligarchs, though it is not formally an oligarchy.

The overriding characteristic of single-party rule is leadership by members of a political party. Prominent examples include the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (1917-1991) and the PRI (Partido Revolucionario Institucional) of Mexico (1929-2000). A ruling party may have a clear guiding ideology and serve as an organization for selecting political talent and unifying political elites.

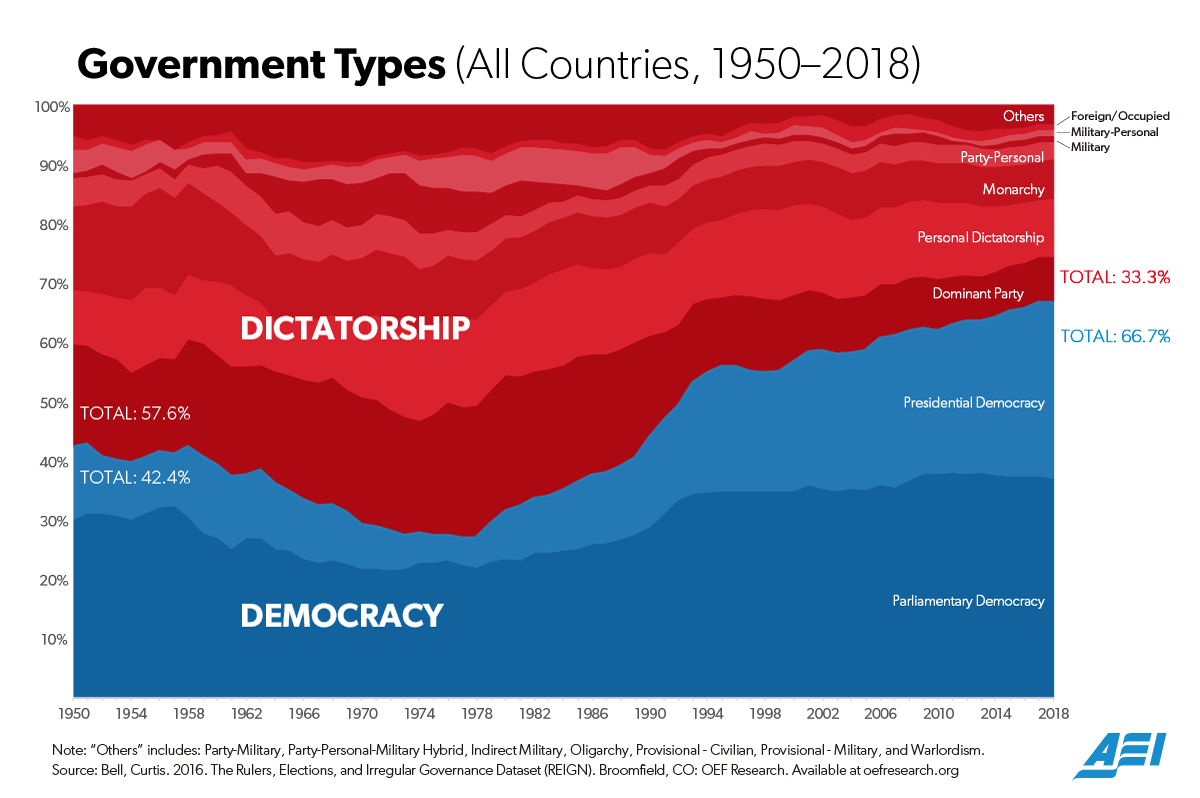

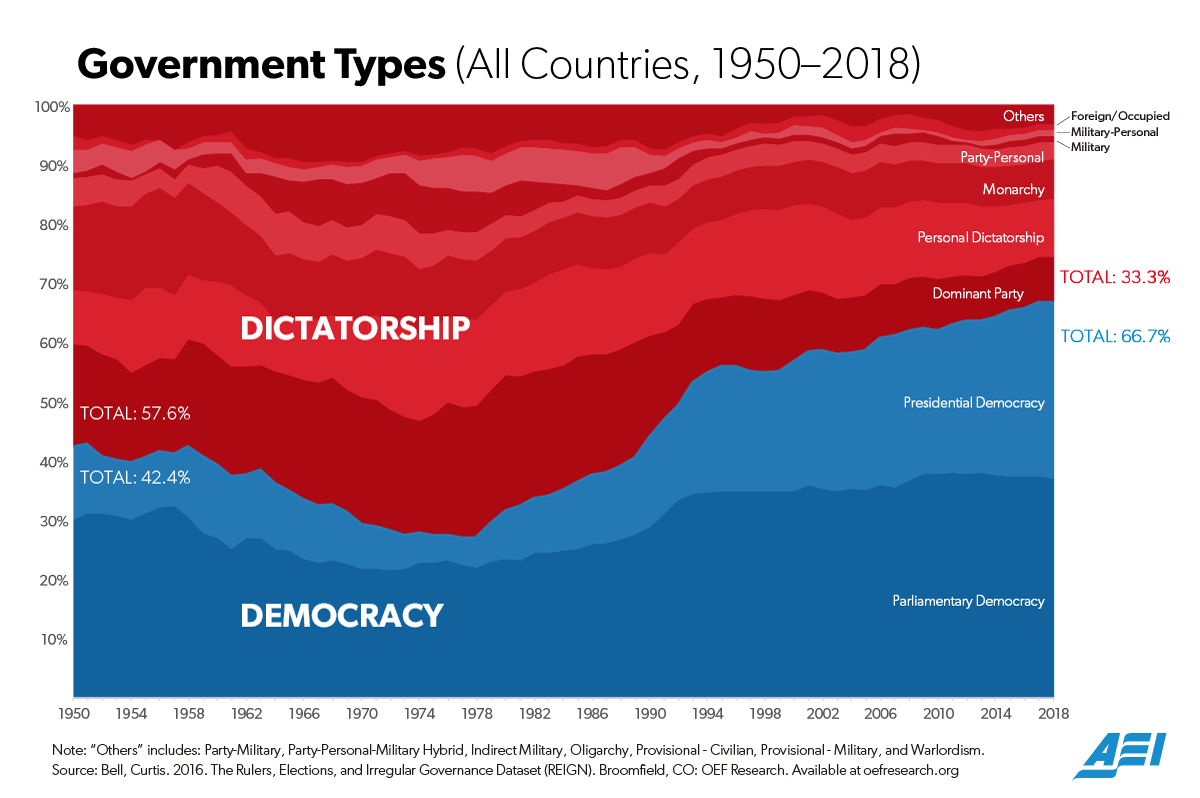

Single-party regimes can be quite stable. For this reason, single-party regimes have been on the rise worldwide since the 1970s.

Source: American Enterprise Institute.

The People’s Republic of China is an example of single-party rule. Political leadership over the billion-plus citizens resides in the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party, a body comprising around twenty individuals. Within the Politburo is the Politburo Standing Committee, typically holding between seven and one dozen high officials. From this inner group, emanate all major decisions guiding contemporary China.

Military rule

Military rule is characterized by military elites, rather than civilians, running the government. A military may rise to political power by possessing the material means – the weapons and organizational capacity – to seize control over a society. Or a population might support military rule because of popular perceptions of the competence of the military, especially if there are charismatic or well-known generals. In some cases, the military might appear to be a particularly stable and orderly institution during a time of political turmoil. This scenario may appeal to certain segments of society (such as economic elites, who especially value stability) or entire war-weary societies.

The role of militaries within a polity is argumentative. On one end of the continuum, developed democracies are grounded in civilian control of the military. For example, the commander-in-chief of the Canadian military is the Canadian monarch. On the other end, in nondemocratic situations, the military is not accountable to the public, even for gross human rights violations. Burma is a prominent example of a country that has been subject to repressive military rule for significant chunks of its post-colonial independence. Burma's military, known as the Tatmadaw, appeared to allow some liberalization and turned toward civilian leadership in the 2010s. But, in the 2020s, i again asserted control over the country and its political apparatus.

During the 20th century, military rule rose and fell in frequency. In the post-World War II period, military regimes peaked at 40 percent of all nondemocracies in the world, then fell to approximately 15 percent of nondemocracies worldwide by the turn of the twenty-first century (Gandhi 2008).

Illiberal and hybrid regimes

The idea of an illiberal regime – one that mixes characteristics of liberal democracies but is decidedly illiberal in other respects – emerged in the twentieth century with the birth of many aspiring democracies after the end of the Cold War (1989-1991), from Romania to Kazakhstan, were sliding into nondemocratic habits.

An illiberal regime might have multiple political parties, partially free media, and partially free and fair elections. Central institutions are weak and subject to manipulation by those with economic power and political influence. Fareed Zakaria observed that, “Far from being a temporary or transitional stage, it appears that many countries are settling into a form of government that mixes a substantial degree of democracy with a substantial degree of illiberalism,” (Zakaria, 1997, p. 24). In short, illiberal democracies exist in an in-between zone where there are nondemocratic institutions or practices in place, yet also some of the markers of democracy. Political scientists question whether illiberal democracy will remain a distinct status for many countries for long stretches of time or whether they will trend more decisively toward either non-democracy or democracy.

Hybrid regimes are separate but related to illiberal regimes. This category acknowledges that many nondemocracies can incorporate more than one type of system. North Korea is an example of a “triple hybrid” – a combination of a single-party system led by a personalist leader (from the Kim dynasty) with a politically powerful military. Further, President Xi Jinping may be moving China toward a hybrid of personalist rule and single-party rule.

Table 5.3.2 offers a summary of the different types of nondemocracies explored in this section, dominant characteristics, and some examples.

Table 5.3.2: Types of nondemocracies, distinguishing characteristics, and examples

| Type of Nondemocracy |

Dominant Characteristics |

Examples |

| Theocracy |

Rule by religious elite in accordance with sacred texts |

Iran, 1979-present |

| Personalist rule and monarchy |

Rule by a single individual; in the case of a monarchy, the monarch derives legitimacy from tradition |

Idi Amin of Uganda, 1971-79

Kingdom of Bahrain, 1971-present

|

| Single-party rule and oligarchy |

Collective rule by a group of elites, in the case of single-party rule via the ruling party |

Soviet Union under the CPSU, 1917/22-1991

Mexico under PRI, 1929-2000

China under the CCP, 1949-present

|

| Military rule |

Rule by military elites |

Burma, 1962-2011

Venezuela, 1899-1945, 1948-1958

|

| Illiberal regime |

Veneer of liberal democratic institutions that are subverted by political elites |

Russia, 1991-present |

| Hybrid regime |

Some combination of the above types |

North Korea, 1948-present |