11.3: Non-state political violence

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 150491

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the differences between civil wars, insurgencies, and guerilla warfare, as well as terrorism and revolution.

Introduction

As we stated earlier, a non-state actor is a political actor not associated with a government. Generally speaking, non-state political violence is by the type of action, rather than the type of actor. For example, terrorists can participate in insurgencies and/or civil wars, whereas guerillas can engage in terrorist actions.

Insurgencies/Civil Wars

In the simplest term, a civil war is an armed conflict between two or more groups where one of the combatants is the government. Does this mean then that an armed engagement between a street gang and a police unit constitutes a civil war? The answer would be no. Remember, political violence is defined as the use of physical harm motivated by political intentions.

According to Sambanis (2004), to meet the definition of civil war, a conflict must be between a rebel group and the government who are politically and militarily organized with stated political objectives that take place in the territory of a state that is a member of the international system with a population of at least 500,000. In addition to these general requirements, there are additional critical characteristics in distinguishing civil wars from the rest of armed engagement. The violence cannot be one-sided, and there needs to be sustained violence.

What then distinguishes civil war from other types of violence (e.g., riots, terrorism, and coup d’etat)? First, civil wars are notated for the level of destruction. Wars within a country are often devastating. The US Civil War (1860-1865) killed over 600,000 people, and its scars are still felt to this day. Given this, most scholars have adopted a numerical threshold of 1,000 deaths when defining political violence, according to the Correlates of War project. However, strict application of this threshold can exclude cases that otherwise meet the definition of civil war.

Given the power dynamics involved in civil wars, the weaker-side (typically the rebels) often relies on certain techniques when challenging the government. This reliance on insurgency tactics is what characterizes a civil war. An insurgency is an act of uprising or revolt against a government and/or the state, and is closely related to the concept of a rebellion. Insurgents claim that they represent the will of the people against a government that no longer represents them. For many insurgents then, the ultimate goal is the overthrow of the government, which in that case makes them revolutionaries. For other insurgents, their state goal may be secession, or if secession is not an attainable goal, then some level of political autonomy.

Insurgents use particular tactics because of the power imbalance faced against the state. Even in a situation where the state is facing extinction as a functioning political entity, the state still often has overwhelming firepower. As such, the challenging side needs to be creative and innovative since the insurgent’s probability of success is much lower, especially in head-to-head combat.

Guerilla warfare is similar to insurgency, and often the phrases are interchangeable. This tactic occurs when small, lightly armed bands use military tactics, including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tactics, and mobility, to fight a larger and less-mobile traditional military. These fighters usually do not engage in mass mobilization practices. Unlike insurgents who claim to represent the will of people, guerillas tend to represent the interests of certain groups, and not necessarily the entire population.

What causes civil wars? Earlier literature on the onset of civil wars focused on grievances (Gurr, 1993). These grievances often revolve around economic, social, and political rights, as well as demand for political autonomy. They also contribute to the likelihood of communal mobilization, which can lead to political violence Especially, when a group historically has some level of political autonomy and then loses it.

Resentment about the restriction on one's political access appears to drive rebellion amongst various communal groups. Thus, rebellion is an act of violently challenging the government or existing ruler in order to bring attention to the status quo with which the challengers are dissatisfied. In this context, leaders can point to legitimizing their cause and propelling the movement. As the level of grievances increases within a group, the easier it becomes for leaders to recruit potential rebels. Eventually, rebellion and civil war can occur.

Collier and Hoeffler (2004) argue that “the incidents of rebellion are not explained by motive, but by the atypical circumstances that generate profitable opportunity”. More specifically, factors associated with the cost of and the availability of financing the rebellion, the relative military advantage of the potential rebel group, and the pattern of demographic dispersion are robust indicators of whether rebellion is an attractive option for opportunistic actors. In addition, rebellion is most likely when participants have low incomes. The basic idea: if joining the rebel movement appears to be more profitable for the individuals, it incentivizes the desire to participate, which in turn determines if a rebellion remains viable.

Finally, Fearon and Laitin (2003) argue that civil war is understood through favorable environments. In other words, an insurgency can be viable and sustained under certain conditions: mountainous terrain, contiguous cross border sanctuaries, and an easily recruited population. These conditions favor insurgents given the asymmetric distribution of power between the rebels and government forces.

Non-State Terrorism

Terrorism is a violent act that generally targets noncombatants for political purposes. Religion, ethno-racial factors, and extreme political ideology can be primary motivations for extreme groups to resort to violence. However, it is evident that mere membership in a particular religious or ethnic group is not always causing one to commit these violent acts. So when and why do political extreme groups commit violence?

In the literature on the origins of terrorism, there are two dominant schools of theoretical explanation:

- psychological relies on the idea that the violence itself is the desired outcome as opposed to being the means to the end. Post (1990) claims that “individuals become terrorists in order to join terrorist groups and commit acts of terrorism.”

- rational choice explanations center around the idea that the act of violence is amongst many alternatives from which an extreme group may choose. Simply put, when the expected benefit of a terrorist act outweighs the cost of such behavior and produces the highest expected utility, then such an act becomes the most strategically sound option for a group.

If the United States military were to fight an existing terrorist group on U.S. soil, the U.S. would most likely win. Thus, most terrorist groups to do deploy large-scale units on US soil. Instead, a terrorist group may attack the US where it is most vulnerable - targeting noncombatant targets, such as civilians. On September 11th, 2001, al-Qaeda’s main target was the World Trade Center, the financial nerve center of the country. Military targets, such as the Pentagon, were also hit. But, the goal was to put pressure on the US government to change its foreign policy and international behavior. If we were to use the rational choice explanation of terrorism, then the 9/11 attacks were committed by a group engaged in a willful strategy to accomplish a political outcome.

The effectiveness of non-state terrorism is mixed. Terrorist action can lead to a specific change in government policy. However, there have been few notable overall shifts in foreign policy. For example, in 2004, al-Qaeda bombed several train stations in Madrid as a reaction to the Spanish government's involvement in the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq. The attacks took place right before the national elections and influenced how Spanish citizens voted. Once the new government came in, they withdrew Spanish forces from coalition fighting in Iraq. However, the attacks in Madrid did not change the overall Iraq War. Other countries refused to change course.

Terrorist action can cause unintended government policy changes. For example, the 9/11 attackers did not intentionally desire to change airport policies in the US. Yet now, all travelers in the US have to endure more intrusive safety protocols, including x-rays, taking off one’s shoes, opening up carry-on bags, prohibition of liquids, etc. Prior to these attacks, anyone could enter an airport, without as much intrusion. For example, people were able to go through security without a ticket and walk their loved ones to the gate. Similarly, they could wait at the gate when welcoming back their loved ones. These privileges no longer exist.

Sometimes the stated purposes of a terrorist organization fail completely. The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) called for the creation of a caliphate, which is essentially a state run by Islamic political authorities, in the areas of Syria and Iraq. A caliph is believed to be the rightful successor to the Prophet Muhammad, which is an important concept in the history of Islam. Yet despite the best efforts of ISIS, the caliphate did not last. Syrian, Russian, Kurdish, and U.S. forces largely defeated ISIS in 2019. Even though ISIS committed violence and killed many non-combatants, they ultimately failed to achieve their primary political goal.

So how do we protect ourselves from a potential terrorist attack? Most countries develop counterterrorism policies. One way is to cut off terrorist financing by monitoring incoming and outgoing financial transactions, such as wire transfers and bank deposits. Other examples include extensive background checks for international student visas and retinal and fingerprint scans at border checkpoints. The European Union (EU) has worked to deradicalize convicted terrorists, as well as developed a Radicalization Awareness Network (RAN). According to the European Commission, “The RAN is a network of frontline practitioners who work daily with both those vulnerable to radicalization and those who have already been radicalised.” (European Commission, n.d.)

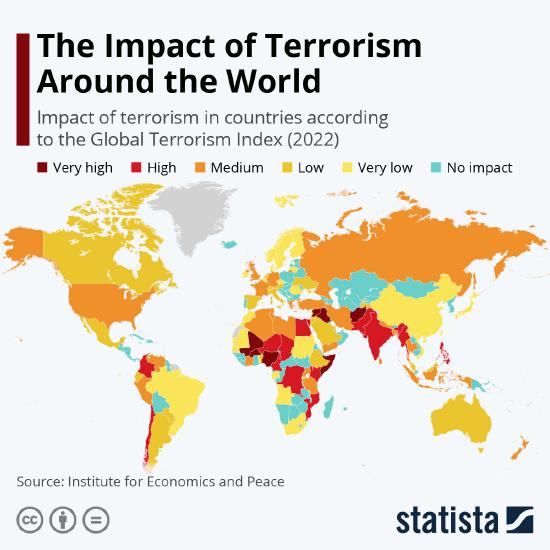

A full-screen version of this image is available here: The Impact of Terrorism Around the World

Revolution

Journalists will label news where a group of citizens politically (and often violently) protest and challenge the government in power as a revolution. An example includes current pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong. Even the participants of the protest have used the word in their slogan, “Liberate Hong Kong, the Revolution of Our Times.” While journalists can use the word, generally speaking describing the struggle as a revolution may not be appropriate.

According to Skocpol (1979), a revolution is a public seizure of the state in order to overturn the existing government and regime. This definition has three important parts.

- First, there has to be public participation in the movement. This characteristic differentiates from other types of political violence, such as a coup d’etat. While many political challenges and violence are initiated by political elites, a revolution must be supported by the general public.

- Second, the main purpose of a revolution is the public seizure of the state. Other types of political violence may not require the seizure of the state. Some politically violent actors can achieve their goals with concessions from the state. For example, some insurgents may settle for an expansion of voting rights or meaningful protection of civil rights. Or, some terrorists may settle for a change in policy. However, a revolution will end with the rebel group in control of the state apparatus, taking full control over the function of the government.

- Third, once the state is captured by the rebels, there will be a shift in the regime. This characteristic is critical when attempting to differentiate a revolution from all other types of political violence against the state. Without a regime change, such actions are classified under other types of political violence (e.g., civil war).

The Russian Revolution of 1917 is a great example of a revolution. It marked the end of centuries of imperial Russian rule, with the assassination of the Romanov family in 1918. The ensuing civil war saw the communists, or Bolsheviks, fight under Vladimir Lenin. Their red army fought against the white army, a loose association of loyalists, capitalists, and other elements. In 1923, the success of the communists led to a dramatic reordering of Russian society. A largely agrarian society was collectively industrialized in the ensuing decades, and new social norms were introduced.

In some cases, revolutions may occur without violence. Nonviolence tactics can include protests, boycotts, sit-ins, and civil disobedience. Where nonviolent revolutions differ is that the movement’s leaders convince the state’s military, or some portion thereof, that the state is better off under a new regime. It is not a coup d’etat per se, as a coup d’etat is led by military elites. In other words, the military either refuses to intervene, and/or abandons the regime in power entirely. When that happens, the reigning military authority will work with the new regime to maintain peace and security.

The fall of communist regimes is an example of a non-violent revolution. The Soviet Union had installed loyal regimes in Eastern European countries in the aftermath of World War II. As part of the Warsaw Pact, countries such as Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, and East Germany were satellite states, dependent on the Soviet Union for their legitimacy and survival. When popular uprisings occurred in Hungary (1956) and Czechoslovakia (1968), Soviet forces rolled in, quelling any hopes of democracy. When popular uprisings occurred again in 1989, Soviet forces withdrew this time, allowing the puppet communist regimes to collapse. Eastern Europe quickly adopted democratic capitalist models. Little violence occurred, with the exception of the execution of Nicolae Ceaușescu in Romania.