24.2: Social Democracy

- Page ID

- 173051

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)During the Interwar period, democratic experiments often ended in fascism. After World War II, stable democratic governments emerged that still exist today, albeit in modified forms such as France. The governments of Western Europe, except Spain and Portugal, granted the right to vote to all adult citizens after the war, including women. (Although Switzerland would not give women the right to vote until 1971!)

The people of Europe had simply fought too hard to return to the conditions of the Great Depression or the bitter class struggles of the pre-World War II period. Thus, one of the plans anticipated by wartime governments was recompense for the people who had endured and suffered through the war - this phenomenon is sometimes referred to as the “postwar compromise” between governments and elites on the one hand and working people on the other. In addition, a specific form of democratic politics and market economics emerged: “social democracy,” the commitment on the part of governments to ensure the legal rights of its citizens, a base minimum standard of living, and access to employment opportunities.

Within the commitment to social democracy, the modern welfare state came into being. The driving principle is that it is impossible to be happy and productive without certain basic needs being met. The most important ones are adequate healthcare and education, both priorities that the governments of postwar Western Europe embraced. By the end of the 1950s, 37% of the income of Western European families was indirect, subsidies “paid” by governments in the form of housing subsidies, food subsidies, health care, and education. European governments devoted four times more income to social services in 1957 than they had in 1930.

The results of state investment in citizen welfare were striking. By the end of the 1960s, most Western European states provided free high-quality medical care, free education from primary school through university, and various subsidies and pensions. Because of the strength of postwar leftist (both communist and socialist) parties, trade unions won considerable rights, with workers entitled to pensions, time off, and regulated working conditions. Thus, as the economies of the Western European states expanded, their citizens enjoyed standards of living higher than any generation before them, in large part because wealth was distributed much more evenly than it had ever been.

The welfare state was paid for by progressive taxation schemes and a very large reduction in military spending. Western Europe’s alliance with the US, and European commitment to the UN, made it politically feasible to greatly reduce the size of each country’s military. Quite simply, countries expected the US to keep the threat of a Soviet invasion in check. Even as military spending skyrocketed for the US and the Soviet Union, it dropped to less than 10% of the GDP of the UK by the early 1960s and steadily declined in the following years. Likewise, as a result of the decolonization trend, there was no longer a need for large imperial armies to control colonies. Instead, “control” shifted to a model of economic relationships between the former colonial masters and their former colonial possessions.

Meanwhile, the far right had been completely compromised by the disastrous triumph of fascism. In the aftermath of World War II, far-right politicians were forced into political silence by the shameful debacle that had resulted in their prewar success. In turn, the far left, namely communists, were inextricably tied to the Soviet Union. In the immediate postwar period, the USSR was widely admired for having defeated the Nazis on the eastern front at a tremendous cost to its people. However, over time, the USSR quickly came to represent a threat of tyranny to most people in the West, especially as it came to dominate the countries of the eastern bloc. As the existence of Soviet gulags became increasingly well known, western communist parties struggled to appeal to anyone beyond their base in the working class. For example, 30% of the electorate in France and Italy voted communist in the immediate aftermath of the war, but that percentage shrank steadily in the following decades.

Thus, with the right compromised by fascism and the left by communism, the parties in power were variations on the center-left and center-right, usually parties that fell under the categories of “Socialists” (or, in Britain, Labour) and “Christian Democrats.” For at least thirty years following the war, neither side deviated significantly from support for social democracy and the welfare state. The ideological divisions had to do with social and cultural issues, such as support or opposition to women’s issues and feminism, the stance toward decolonization, the proper content of the state-run universities, and so on, rather than the desirability of the welfare state.

These “socialists” were only socialistic in their firm commitment to fair treatment of workers. In some cases, socialist parties held onto the traditional Marxist rhetoric of revolution as late as the early 1970s, but it was increasingly obvious to observers that revolution was not in fact a practical goal that the parties were pursuing. Instead, socialists tended to champion a more diffuse, and prosaic, set of goals: workers’ rights and protections, support for the independence of former colonies, and eventually, sympathy and support for cultural issues surrounding feminism and sexuality.

In turn, Christian Democracy was an amalgam of social conservatism with a now-anachronistic willingness to provide welfare state provisions. Christian Democrats (in the case of Britain, the Conservative “Tory” Party) tended to oppose the dissolution of empire until decolonization was in full swing by the 1960s. While willing to support the welfare state in general, Christian Democrats were staunchly opposed to the more far-reaching demands of labor unions. Against the cultural tumult of the 1960s, Christian Democrats emphasized what they identified as traditional cultural and social values. Arguably, the most important political innovation was that the European right accepted liberal democracy as a legitimate political system for the first time. Generally, there were no further mainstream political parties or movements that attempted to create authoritarian forms of government.

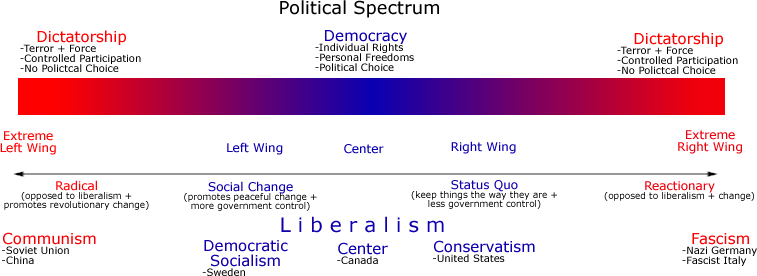

Political Spectrum with Historic Examples