2.1.2.1.3: Postcolonial, Racial, and Ethnic Theory- An Overview

- Page ID

- 117485

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

As you’ve seen throughout this textbook, the field of English or literary studies has changed significantly through the years. At one time, to study English meant to study only literature from England. In fact, it meant to study, almost exclusively, poetry from England. As we see in Chapter 4, the poetry that English students read for the majority of the field’s history was almost exclusively written by men. It may not surprise you to learn that the majority of the men that English students read came from Western cultures and were white. The experiences of minorities (within Western culture) and non-Western people were largely excluded from the canon. When their experiences did appear in widely read books, poems, plays, and essays, their experiences were usually filtered through perspective of a white author.

Over the past decades, many literary scholars have begun working to change this reality. Drawing from a range of disciplines, including history, anthropology, and sociology, these scholars have demonstrated how the literary canon excludes the voices of minority and non-Western writers, thinkers, and subjects. They have exposed attitudes of prejudice within canonical works. They have also worked to recover and celebrate works by writers from previously ignored or denigrated racial and ethnic backgrounds. Though their subjects vary widely—from the African American experience in the United States to those of Indians living under British colonial rule—scholars interested in racial, ethnic, and postcolonial studies share a conviction that literature is not politically neutral. Instead, they argue that literature both reflects and shapes the values of the cultures that produce it and that literary critics have a duty to analyze and often critique the cultural values embedded in the texts we study.

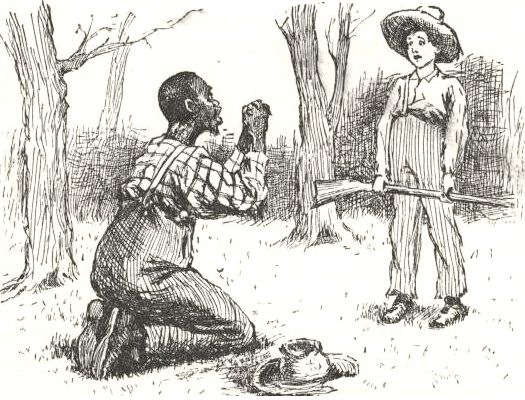

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Illustration by Edward Winsor Kemble for Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884).

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Illustration by Edward Winsor Kemble for Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884).

Think, for instance, of the frequent debates that have arisen over Mark Twain’s novel Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (you can read Huck FinnMark Twain, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1912; University of Virginia Library Electronic Text Center, 1995), http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/Twa2Huc.html. in its entirety at http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/Twa2Huc.html). For years, literary critics, scholars, students, and parents have debated whether the novel, written by a white American man, should be considered racist (and, if so, whether it should be taught in schools). These debates center on three major issues: (1) the novel’s depiction of Jim, the runaway slave who is simultaneously the novel’s moral center and a frequent object of ridicule; (2) the novel’s frequent use of a racial epithet to describe its African American characters; and (3) the heavy dialect through which the speech of black Americans is presented in the book. Schools have frequently debated banning Twain’s novel, often in response to the concerns of parents or students.See Gregory Roberts, “‘Huck Finn’ a Masterpiece—Or an Insult,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, November 25, 2003, http://www.seattlepi.com/local/article/Huck-Finn-a-masterpiece-or-an-insult-1130707.php. There is no easy solution to these debates. As literary critic Stephen Railton put it nearly thirty years ago: “Is Huck Finn racist? Yes and no; no and yes.”Stephen Railton, “Jim and Mark Twain: What Do Dey Stan’ For?” The Virginia Quarterly Review. http://www.vqronline.org/articles/1987/summerrailton-jim-mark/. However you feel about this novel, however, these debates illustrate the importance of literary critics considering issues of race, ethnicity, and culture as they read and interpret literature.

Though it has happened more slowly than many cultural critics would like, the literary canon has shifted in the past decades to reflect a wider sense of who writes literature and what we should learn from it. The fact that we study American literature at all reflects an earlier shift away from a strict focus on English writing. Moreover, students in American literature classrooms today study more writers of color than did students even twenty years ago. Some African American writers are now studied so frequently they could be called canonical, including Olaudah Equiano, Phillis Wheatley, Frederick Douglass, Charles Chesnutt, Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, Alice Walker, and Toni Morrison. American literature classes often cover writing by Native American writers, such as Leslie Marmon Silko, Louise Erdich, and Sherman Alexie, and by Hispanic, Chicano/a, or Latino/a American writers such as George Santayana, Isabel Allende, and Gary Soto. Moreover, British literature classrooms now routinely include works by authors from former British colonies, such as Chinua Achebe (Nigeria), Jean Rhys (Dominica), Salman Rushdie (India), and Anita Desai (India). Finally, courses in world literature regularly teach minority and/or postcolonial writers who compose in languages other than English.

We recognize that these are incomplete lists. Indeed, even separating authors into these distinct categories can be problematic, as many writers span geographic regions, ethnic identities, or racial backgrounds. Nevertheless, these names can help get us started thinking about the diverse voices that literature classrooms now include. Of course, scholars working in these fields would point out that there is much work yet to be done to build a truly representative curriculum. Though minority and non-Western writers are now studied regularly, they still occupy relatively small places in most literature classrooms and curricula.

Your Process

- What minority or non-Western writers have been part of your literary education to this point? Jot down a few examples.

- Now think about how those writers shaped your understanding of our literary inheritance. How did reading those writers change your ideas about literature, culture, or history? How would your literary education have been different with a textbook of thirty years ago that largely excluded nonwhite voices?

- How does your cultural background shape your response to these questions?

Scholars working in these fields often seek to challenge Eurocentrism, which is a worldview that considers European societies (and those closely related to them, such as white American society) as the model to which other societies should aspire. Taking a slightly different focus, the critic Edward Said coined the term Orientalism, which refers to a set of false assumptions and stereotypes that Western cultures maintain about societies other than themselves.Edward W. Said, Orientalism (New York: Random House, 1994). These Others are sometimes portrayed as excessively bad (demonic others) and sometimes as excessively beautiful (exotic others), but neither view actually builds a true picture of non-Western societies or people. In other words, literary critics are wary of texts in which a foreign society is portrayed as ideal, just as they are when a foreign society is portrayed as depraved.

Looking at literature through the lens of social and cultural identity often requires that critics read beyond the surface meanings of texts and think about the ethnic, cultural, and social implications of the words on the page. For instance, let’s consider Phillis Wheatley’s “On being brought from Africa to America,” which was published in her 1773 collection, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral:

On Being Brought from Africa to America.

’TWAS mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their colour is a diabolic die.”

Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain,

May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.Phillis Wheatley, “On Being Brought from Africa to America,” in Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (Denver: W. H. Lawrence, 1887), 17.

Wheatley was a slave, brought to Boston on the slave ship Phillis in 1761 and owned by John and Susanna Wheatley, who gave her an education, which was uncommon for slaves at the time. On the surface, Wheatley’s poem seems to praise the system of slavery that brought her to America, noting that it was “mercy” that “brought [her] from [her] Pagan land.” With that latter phrase she seems to disown her heritage as simply pagan, a “benighted” contrast to the Christian education she has received in the United States. We might even accuse Wheatley of mimicry, or attempting to imitate the language and (as you can see in the following engraving) dress of the ruling class.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Portrait by Scipio Moorehead as a frontispiece to Phillis Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects… (1773).

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Portrait by Scipio Moorehead as a frontispiece to Phillis Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects… (1773).

However, scholars of African American literature might urge us to read the poem as a subtle critique of the American slave system. In her article “A Slave’s Subtle War: Phillis Wheatley’s Use of Biblical Myth and Symbol,” Sondra O’Neale begins by insisting that “any evaluation of Phillis Wheatley must consider her status as a slave.” O’Neale notes that a slave who wanted to write during this time period “first had to acquire the requisite language skills.” Then “appropriate whites had to authenticate the writer’s mental and moral capacity, and then the slave’s master had to agree that the slave could publish the work. Moreover, the slave’s offering was carefully censored to ensure that it was in no way incendiary.”Sondra O’Neale, “A Slave’s Subtle War: Phillis Wheatley’s Use of Biblical Myth and Symbol,” Early American Literature 21, no. 2 (1986): 144–45. In other words, Wheatley could not write a bald condemnation of slavery; her owners held absolute sway over both her writing and her person, and to be published, she had to write within the constraints imposed on her by whites invested in keeping the slave system intact.

For O’Neale, Wheatley “challenged eighteenth-century evangelicals in their cherished religious arena by redeploying the same language and doctrine that whites had used to define the African, thereby undercutting conventional colonial assumptions about race and skin color.”Sondra O’Neale, “A Slave’s Subtle War: Phillis Wheatley’s Use of Biblical Myth and Symbol,” Early American Literature21, no. 2 (1986): 145. In the poem, Wheatley refers to “Negros, black as Cain.” In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, many religious and political commentators taught that African people descended from the biblical Cain, who was cursed by God after murdering his brother, Abel. In the King James Bible, it says “the LORD set a mark upon Cain” to identify him to other people, and many white commentators argued that this mark was a dark skin tone.Gen. 4:15 (King James Version). By associating black people with Cain, whites implied that blacks were inferior people both physically and morally—marked as “other” than whites, whom they considered normal.

Wheatley’s poem reappropriates these ideas into a critique of Christians who refuse to acknowledge the brotherhood of African people: “Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain.” First, the terms “Christian,” “Negroes,” and “black as Cain” are presented in a close sequence, as Wheatley conflates her presumably white readers (“Christians”) with herself and her people (“Negros, black as Cain”). In the next line she insists that black Americans “May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train,” where they would, presumably, stand shoulder-to-shoulder with white Christians. Wheatley notes, “Some view our sable race with scornful eye,” and say “Their colour is a diabolic die,” but she refuses this mischaracterization of her people. They are not “diabolic”—a “demonic other”—but instead equal in potential to white Americans. Though she cannot directly condemn slavery, Wheatley’s poem simultaneously evokes and calls into the question prejudiced ideas about African Americans. By writing such refined poetry, Wheatley embodies the mental equality of blacks and whites, and in these final lines she insists on that equality. If her readers grant this last concession, however—if they agree that blacks and whites can indeed join the same “angelic train”—then the systems of denigration and oppression they support will be exposed as resting on false pretenses. In other words, we can read Wheatley’s mimicry as subversive. She is an African American writer working within the strict limitations of the slave system to write and distribute poetry that subtly undermines that very system.

Your Process

Read the following Wheatley poem, “To the University of Cambridge, in New-England.” As you read, consider what underlying messages Wheatley might seek to convey, as in the poem we discussed previously. Jot down your ideas.

While an intrinsic ardor prompts to write,

The muses promise to assist my pen;

’Twas not long since I left my native shore

The land of errors, and Egyptian gloom:

Father of mercy, ’twas thy gracious hand

Brought me in safety from those dark abodes.

Students, to you ’tis giv’n to scan the heights

Above, to traverse the ethereal space,

And mark the systems of revolving worlds.

Still more, ye sons of science ye receive

The blissful news by messengers from heav’n,

How Jesus’ blood for your redemption flows.

See him with hands out-stretcht upon the cross;

Immense compassion in his bosom glows;

He hears revilers, nor resents their scorn:

What matchless mercy in the Son of God!

When the whole human race by sin had fall’n,

He deign’d to die that they might rise again,

And share with him in the sublimest skies,

Life without death, and glory without end.

Improve your privileges while they stay,

Ye pupils, and each hour redeem, that bears

Or good or bad report of you to heav’n.

Let sin, that baneful evil to the soul,

By you be shun’d, nor once remit your guard;

Suppress the deadly serpent in its egg.

Ye blooming plants of human race divine,

An Ethiop tells you ’tis your greatest foe;

Its transient sweetness turns to endless pain,

And in immense perdition sinks the soul.

Wheatley is an interesting example because her work speaks to the concerns of scholars interested in the African American literary tradition and scholars interested in issues of conquest and colonialism. Wheatley wrote, after all, when Massachusetts was a British colony, and she came to Massachusetts after being forcibly seized from her home in either Senegal or Gambia, in West Africa. Next we’ll look at another text that can help us understand the concerns of postcolonial critics. Nearly 150 years after Wheatley was captured, Joseph Conrad published one of the most famous works ever written about the African continent, Heart of Darkness (1899).Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness (1902; University of Virginia Electronic Text Center, 1993), etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/mo...c/ConDark.html.

Your Process

- As we’ve suggested throughout this text, these process papers will make more sense if you are familiar with the literary work under discussion. For this section, you should read Joseph Conrad’s novella, Heart of Darkness, which you can find in full as an e-text provided by the University of Virginia (etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/mo...c/ConDark.html).

- As you read, pay particular attention to the way that Conrad portrays relationships between European and African characters in the text.

Though Heart of Darkness was written, in part, as a critique of Belgian colonialism and commerce in the Congo, many postcolonialist critics have pointed out that the novella perpetuates attitudes of racism and Eurocentrism through its portrayal of Africans.

Most famously, Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe wrote in “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness” that the novella “projects the image of Africa as ‘the other world,’ the antithesis of Europe and therefore of civilization, a place where man’s vaunted intelligence and refinement are finally mocked by triumphant bestiality.”Chinua Achebe, “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness,’” in Hopes and Impediments: Selected Essays (New York: Anchor, 2012). Achebe notes that few Africans are allowed to speak in Conrad’s text. Through most of the novella, he notes, the African characters simply make noises—grunts and babble and sounds. Only two African characters speak: one to express cannibal propensities and another to announce the death of the white enigma, Mr. Kurtz. Achebe insists, despite the stylistic merits of Conrad’s work (which he admits are considerable), that “the real question is the dehumanization of Africa and Africans which this age-long attitude has fostered and continues to foster in the world. And the question is whether a novel which celebrates this dehumanization, which depersonalizes a portion of the human race, can be called a great work of art. My answer is: No, it cannot.”Chinua Achebe, “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness,’” in Hopes and Impediments: Selected Essays (New York: Anchor, 2012). In other words, Achebe insists that the text’s aesthetic qualities cannot and should not redeem its cultural and racial attitudes. Such a commitment to the political and social implications of literature characterizes much ethnic criticism.

If that attitude seems extreme, consider the following excerpt from a 2003 article in the British newspaper The Guardian. It’s written by Caryl Phillips, who initially met with Achebe to defend Joseph Conrad’s writing against Achebe’s critiques, but their conversation took another turn:

“I am an African. What interests me is what I learn in Conrad about myself. To use me as a symbol may be bright or clever, but if it reduces my humanity by the smallest fraction I don’t like it.”

“Conrad does present Africans as having ‘rudimentary’ souls.”

Achebe draws himself upright.

“Yes, you will notice that the European traders have ‘tainted’ souls, Marlow has a ‘pure’ soul, but I am to accept that mine is ‘rudimentary’?” He shakes his head. “Towards the end of the 19th century, there was a very short-lived period of ambivalence about the certainty of this colonising mission, and Heart of Darkness falls into this period. But you cannot compromise my humanity in order that you explore your own ambiguity. I cannot accept that. My humanity is not to be debated, nor is it to be used simply to illustrate European problems.”

The realisation hits me with force. I am not an African. Were I an African I suspect I would feel the same way as my host. But I was raised in Europe, and although I have learned to reject the stereotypically reductive images of Africa and Africans, I am undeniably interested in the break-up of a European mind and the health of European civilisation. I feel momentarily ashamed that I might have become caught up with this theme and subsequently overlooked how offensive this novel might be to a man such as Chinua Achebe and to millions of other Africans. Achebe is right; to the African reader the price of Conrad’s eloquent denunciation of colonisation is the recycling of racist notions of the “dark” continent and her people. Those of us who are not from Africa may be prepared to pay this price, but this price is far too high for Achebe. However lofty Conrad’s mission, he has, in keeping with times past and present, compromised African humanity in order to examine the European psyche.Caryl Phillips, “Out of Africa,” The Guardian, February 21, 2003, http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2003...s.chinuaachebe.

Phillips begins to understand that he shares, to some degree, Conrad’s Eurocentric perspective and thus has not to this point understood Achebe’s African perspective. When Phillips begins to see how Conrad’s focus on the novella’s European characters leads him to disregard its African characters, Phillips also begins to accept Achebe’s postcolonial critique of the novel.

Your Process

- Listen to Chinua Achebe’s 2009 interview with NPR about Heart of Darkness(http://www.npr.org/templates/story/s...ryId=113835207).Robert Siegel, “Chinua Achebe: ‘Heart of Darkness’ Is Inappropriate,” All Things Considered, NPR, audio, October 15, 2009, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/s...ryId=113835207. Can you understand why Achebe, as an African, takes such umbrage at the portrayal of Africans in this canonical novel? Should such concerns shape what we read in literature classrooms?

- You can read Caryl Phillips’s full article about his discussion with Achebe at http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2003...s.chinuaachebe. How does Phillips’s epiphany square with your own thoughts about Achebe and Conrad?

- To learn more about postcolonial writers and critics, visit the Postcolonial Web (http://www.postcolonialweb.org/misc/authors.html) or read Deepika Bahri’s “Introduction to Postcolonial Studies” (http://www.english.emory.edu/Bahri/Intro.html).George P. Landlow, “Home Page,” The Postcolonial Web, http://www.postcolonialweb.org/; Deepika Bahri, “Introduction to Postcolonial Studies,” Dept. of Postcolonial Studies, Emory University, http://www.english.emory.edu/Bahri/Intro.html.

To sum up, when you want to read with an eye toward racial, ethnic, or postcolonial issues, you should consider the following questions:

- How does this work represent different groups of people? Does it valorize one particular culture at the expense of another? Are characters from particular groups portrayed positively or negatively? Does the work employ stereotypes or broad generalizations?

- How does this work present political power and/or domination? Are there clear lines drawn between conquerors and conquered people in the work? Does the work seem to argue that these lines are appropriate, or does it challenge the divisions between colonizer and colonized?

- What is the historical or cultural context of the work? Is the story set during a time of conflict or peace? Is the story set in a location where one culture colonized another? Does the story unfold before the colonial period, during the colonial period, or after the colonial period?

- Can you discern any particular political agendas at work in the text? That is, does the novel, story, poem, play, or essay seem to make an argument about racial relations, ethnic identity, or political oppression?

The theories we outline in this chapter share many concerns but can be applied in many different ways. To that end, we provided three sample papers in this chapter. Each uses a slightly different lens to investigate a given literary text. Please review all the papers since they will prepare you for the chapter’s conclusion, which will synthesize the insights of all three papers.