2.1.2.8.5: Article- The Hero’s Journey

- Page ID

- 117900

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

Before You Read

Discuss the following questions with a classmate.

- What makes someone a hero?

- What do heroes do in movies?

- Why do people love stories about heroes?

- What are some stories you can think of that have a hero?

- Skim the next reading. What do you think is the author’s purpose of the text: to inform, entertain, or to persuade? How will that affect the way you take notes on the reading?

Vocabulary in Context

This article has a lot of useful vocabulary for reading the rest of the chapter and for use in your next essay. Try to guess the vocabulary in bold.

- Chances are this kind of story has been told for millennia, and yet people still love them.

- Many stories that humans have loved throughout time have some interesting patterns, and that there’s a good reason why these kinds of stories strike a chord in us.

- Superhero movies epitomize the hero’s journey and are becoming bigger and bigger blockbusters each year. Even George Lucas himself, the creator of the groundbreaking Star Wars movie series, noted that Joseph Campbell’s book was very influential to him.

- This is the point where the person actually crosses into the field of adventure, leaving the known limits of his or her world and venturing into an unknown and dangerous realm where the rules and limits are unknown.

- The hero may need to fight against foes who are guarding the gate or border of the realm to prevent the hero from coming in.

- While on their way towards their task, the hero might meet some friends, allies, or people willing to help them.

- In between facing ordeals, the hero gets to see more of the fantastic land they are in.

- Not long after she begins her trek on the yellow brick road, Dorothy meets others that will help her on her quest.

- Numerous times she traverses back and forth from Kansas and the land of Oz and other neighboring fantasy lands filled with interesting characters.

- The real reason why ordinary humans like ourselves love these kinds of outlandish storylines is that we want to strive to be heroes ourselves.

Vocabulary Building

Find the word in the paragraph given. Use the synonyms and definition to help.

- P1: surpass, exceed (v.): ______________________________________________________

- P2: a preset pattern (n.): ______________________________________________________

- P4: to be a perfect example of (v.): ____________________________________________

- P5: clearly, in full detail (adv.): _________________________________________________

- P12: a complete and thorough change (n.): ____________________________________

- P14: gentle, kind (adj.): _______________________________________________________

- P17: although (conj.): _________________________________________________________

- P18: equipped (v.): ___________________________________________________________

- P19: a magical or medicinal potion (n.): ________________________________________

- P20: great happiness (n.): _____________________________________________________

- P20: extremely interested (adj.): ______________________________________________

- P27: strange, unfamiliar (adj.): _________________________________________________

- P28: involve (v.): _____________________________________________________________

The Hero’s Journey

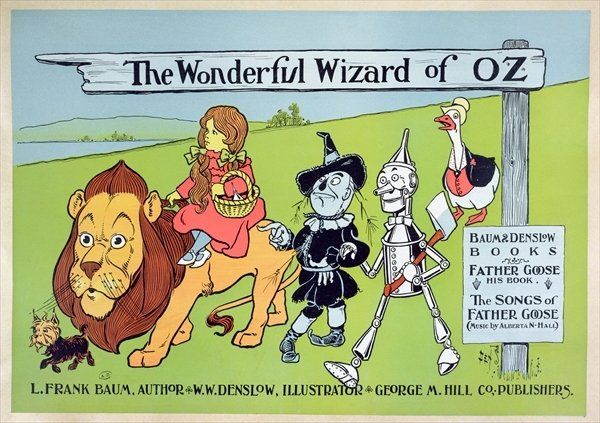

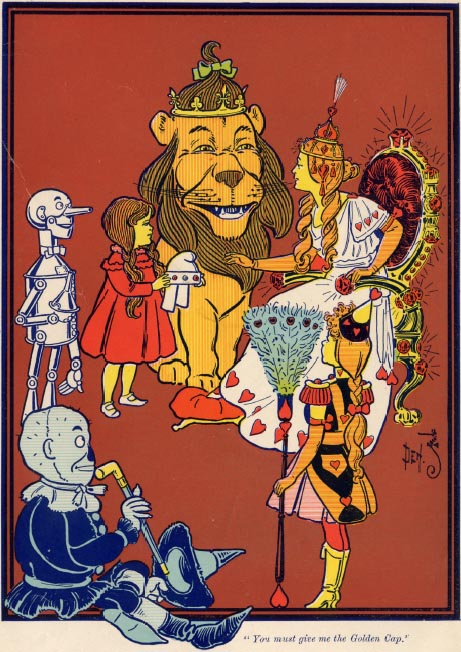

Written by Charity Davenport with material from the Wikipedia article “Monomyth“, $\ccbysa$

Illustrations by W.W. Denslow for L. Frank Baum’s book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, $\ccpd$

Think about one of your favorite movies or stories. Chances are the story has a strong hero that you empathize with and aspire to become. And chances are this kind of story has been told for millennia, and yet people still love them. These stories transcend time and culture.

In narratology and comparative mythology, the monomyth, or the hero’s journey, is the common template of a broad category of tales that involve a hero who goes on an adventure, and in a critical crisis wins a victory, and then comes home changed or transformed.

The study of hero myth narratives started in 1871 with anthropologist Edward Taylor’s observations of common patterns in plots of heroes’ journeys. Later on, hero myth pattern studies were popularized by Joseph Campbell in his 1949 book The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Campbell and other scholars describe narratives of Gautama Buddha, Moses, and Jesus Christ in terms of the monomyth, and notice that many stories that humans have loved throughout time have some interesting patterns, and that there’s a good reason why these kinds of stories strike a chord in us.

The stages of the hero’s journey can be found in all kinds of literature and movies, from thousands of years ago to now. Superhero movies epitomize the hero’s journey and are becoming bigger and bigger blockbusters each year. Even George Lucas himself, the creator of the groundbreaking Star Wars movie series, noted that Joseph Campbell’s book was very influential to him. The hero’s journey can be found in books like Harry Potter, Lord of the Rings, The Chronicles of Narnia, and most other fantasy sci-fi books, legends, fairy tales, and comic book series like Spiderman and Batman. Many video games like The Legend of Zelda, Skyrim, the Final Fantasy and even the Pokémon series carry many elements of the hero’s journey. But fantasies aren’t real. Why do we love these stories so much? Because the monsters might not be real, the witches might not be real, and the magical objects and fantastic settings might not be real. But the struggle is.

But before we talk about that, we need to dive deeper into the different stages of Campbell’s hero’s journey. The following list of stages also describes stages mentioned by other writers, like David Adams Leeming, who wrote a similar book inspired by Campbell’s book in 1981 called Mythology: The Voyage of the Hero, and Christopher Vogler who published The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers in 2007. As you read, think about examples from stories, movies, or books you have read that might fit these stages. You’ll be surprised. As an example, the story of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, America’s most well-known mythology written in 1900 by L. Frank Baum, will be used to help explain the stages. There are many stages–not all monomyths necessarily contain all stages explicitly; some myths may focus on only one of the stages, while others may deal with the stages in a somewhat different order. The stages are divided into three parts–departure, initiation, and return.

Part 1: Departure

1: Unusual Birth

The hero may have an unusual birth or is born with unique powers. They may be born into a royal family but sent off to live with someone with a more ordinary existence. No matter their birth, something is different about them that lies unknown to others and themselves. They may be isolated by others due to this difference.

2: The Ordinary World / Humble Upbringing

Oftentimes, the story starts out in a world not too different from our own, and in contrast to stage 1, the hero might just be your everyday neighbor down the street. In the case of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, the main character Dorothy is just a normal American girl living on a farm in Kansas.

3: The Call to Adventure

Suddenly something happens, and the hero is requested to do a task and /or is taken to a new world. For Dorothy, suddenly a tornado comes, but she is unable to get to the underground shelter in time and so runs into the house. The house is taken away into the sky and later lands in a beautifully colored land of tiny people named the Munchkins. The hero may often find themselves in a fantasy land much different from their home at one point or another.

4: Refusal of and Acceptance of the Call

Often when the call is given, the future hero first refuses to heed it. This may be from a sense of duty or obligation, fear, insecurity, a sense of inadequacy, or any of a range of reasons that work to hold the person in his or her current circumstances. Someone may come to help convince the hero that they are the only ones who can do the task, or they are the best person for the job. Eventually, the hero learns that they must be responsible to complete the task at hand.

5: Supernatural Aid / Mentor & Talisman

Once the hero has committed to the quest, consciously or unconsciously, his or her guide and magical helper appears or becomes known. More often than not, this supernatural mentor will present the hero with one or more talismans or artifacts that will aid the hero later in their quest. In The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, after Dorothy finds herself in a magically colorful land filled with strange little people, the good witch Glinda comes to help Dorothy find her way to the Wizard of Oz, who can help her get home. Glinda gives Dorothy a pair of magical silver shoes (ruby slippers in the 1939 movie version)–shoes from the feet of her evil witch sister that has just been crushed by Dorothy’s house falling on her. Glinda appears every so often during the movie version to help Dorothy along the way.

6: Entering the Unknown: Crossing the Threshold

This is the point where the person actually crosses into the field of adventure, leaving the known limits of his or her world and venturing into an unknown and dangerous realm where the rules and limits are unknown. Although Dorothy has already entered a strange land, she is instructed to follow a yellow brick road in order to reach the Wizard of Oz. At this point, she is only following her mentor Glinda’s orders but doesn’t know what she might find along the road, good or bad.

7: First Battle: Threshold Guardian

This may be the first battle they have, usually shortly after crossing the threshold into the other realm. The hero may need to fight against foes who are guarding the gate or border of the realm to prevent the hero from coming in. The first battle represents the final separation from the hero’s known world and self. By entering this stage, the person shows willingness to undergo a metamorphosis. When first entering the stage, the hero may encounter a minor danger or set back. For Dorothy, it was meeting with the Kalidahs, monsters with bodies like bears and heads like tigers–but at least she had some help.

8: Allies / Helpers

While on their way towards their task, the hero might meet some friends, allies, or people willing to help them. Not long after she begins her trek on the yellow brick road, one by Dorothy she meets a scarecrow, tin man, and cowardly lion, all of whom would also like to seek help from the wizard. Here we can see an example of how the stages should not be considered perfect–because Dorothy’s first battle with the Kalidahs happens after this stage, after she meets her allies.

Part 2: Initiation

9: Road of Trials

The road of trials is a series of tests that the person must undergo to begin the transformation. Often the person fails one or more of these tests, which often occur in threes. This is usually where the most action lies in the story, with the hero coming upon obstacle after obstacle, maybe winning them all or may suffer a few losses. In between facing ordeals, the hero gets to see more of the fantastic land they are in. In The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Dorothy and her three allies face many barriers on their way to the wizard–one of which is a field of poppies that makes some of them fall asleep. Campbell writes, “The hero is covertly aided by the advice, amulets, and secret agents of the supernatural helper whom he met before his entrance into this region. Or it may be that he here discovers for the first time that there is a benign power everywhere supporting him in his superhuman passage.” Through many of Dorothy’s obstacles, she is helped by the people in the different lands she travels through. A giant group of mice helps bring sleeping Dorothy and the lion out of the poppy field to safety.

10: Meeting with the Goddess / Temptress

Along the way, the hero may meet a woman who helps him or may also tempt him to wander away from his path. The meeting with the goddess does not need to be female nor a goddess, but it sometimes involves a romantic relationship with the hero. It could be anyone who helps the hero or gives items to him that will help him in the future. In Dorothy’s case, the goddess here is the wizard. Finally, Dorothy and her crew reach the land of Oz where the wizard lives to ask of him what they desire, with Dorothy’s wish to simply go back home to Kansas. But instead, the wizard will only help her if she agrees to kill the wicked witch of the West and bring back her broomstick.

The woman as temptress has the opposite effect. In this step, the hero faces temptations, often of a physical or pleasurable nature, that may lead him or her to abandon or wander from his or her quest, which does not necessarily have to be represented by a woman. Woman is a metaphor for the physical or material temptations of life, since the hero-knight was often tempted by lust from his spiritual journey.

11: Brother / Father Battle: The Final Showdown

In this step, the person must finally face whatever holds the ultimate power in his or her life, usually the villain or antagonist of the story. In many myths and stories, this is the father or a father figure who has life and death power. This is the center point of the journey. All the previous steps have been moving into this place, and it’s usually the ultimate goal of the hero, and all that follow will move out from it. Although this step is most frequently symbolized by an encounter with a male, it does not have to be a male; just someone or thing with incredible power. In Dorothy’s case, this is meeting with the wicked witch of the West, who Dorothy successfully (albeit accidentally) kills and takes her broomstick.

12: Apotheosis

This is the point of realization in which a greater understanding is achieved. Armed with this new knowledge and perception, the hero is resolved and ready for the more difficult part of the adventure, which for Dorothy is simply going home. In this stage, the hero is also finally recognized as a hero by the people of the realm they are in and the people of their homeland. They may even be immortalized as a god towards the end of the story. Having killed two evil witches that enslaved the beings of their realms, there are many in the magical land that see Dorothy as a powerful hero.

Part 3: Return

13: The Ultimate Reward

The ultimate reward is the achievement of the goal of the quest. It is what the person went on the journey to get. All the previous steps serve to prepare the person for this step, since in many myths the reward is something that has supernatural powers, like an elixir of life, or a plant that makes one immortal, or the holy grail. Sometimes it’s the completion of the quest, like killing a monster that has been attacking the town. Unfortunately for little Dorothy, she doesn’t get what she wanted after fulfilling the wizard’s request because they learn that the wizard doesn’t have any magical powers to help them. Once again they must journey, this time to her mentor Glinda, to find out how to get home again.

14: Refusal to Return

Having found bliss and enlightenment in the other world, the hero may not want to return to the ordinary world to present the reward onto his fellow man. Although a while ago the hero was entering an unknown world, it has become familiar to them, they have made many friends and accomplishments, and thus they may not want to leave to go back home. This is definitely the case for Dorothy, who although frightened yet intrigued by this strange magical land, made lots of new friends, met interesting and helpful strangers, and learned that “home is where the heart is.”

15: Magical Flight / Rescue from Without

Sometimes the hero must escape with the reward, especially if it is something that the gods have been jealously guarding. It can be just as adventurous and dangerous returning from the journey as it was to go on it. This can also be another adventure the hero must complete just to escape the magical land. Now that Dorothy has a new quest to find Glinda, she once again finds ordeals blocking the way and monsters to fight. Dorothy uses the power of a magic cap to call flying monkeys to take her to certain places.

Just as the hero may need guides and assistants to set out on the quest, often he or she must have powerful guides and rescuers to bring them back to everyday life, especially if the person has been wounded or weakened by the experience.

16: The Return Threshold: Home Again

The trick in returning is to retain the wisdom gained on the quest, to integrate that wisdom into a human life, and then maybe figure out how to share the wisdom with the rest of the world. Once Dorothy finally accomplishes her new goal of finding Glinda, Glinda tells Dorothy that what she needed to return home was with her all along–the magical silver (or ruby) shoes on her feet. The others also learned that everything they desire was within them all along. Dorothy learns that home is always where you want it to be.

17: Master of Two Worlds / Restoring the World

This step is usually represented by a transcendental hero like Jesus or Buddha. For a human hero, it may mean achieving a balance between the material and spiritual. The person has become comfortable and competent in both the inner and outer worlds. For the Dorothy in the Oz novels, numerous times she traverses back and forth from Kansas and the land of Oz and other neighboring fantasy lands filled with interesting characters.

18: Freedom to Live

Mastery leads to freedom from the fear of death, which in turn is the freedom to live. This is sometimes referred to as living in the moment, neither anticipating the future nor regretting the past. Essentially, this is the hero’s “happily ever after.” Now the hero has returned home and probably faces a triumphant crowd cheering their return. Now they can rest and enjoy their life, until next time…

Were you thinking of a movie or a story while reading the three stages? Which stages could you easily point out in the story? Which were missing? And how does that affect the story’s plot? It’s just as important to point out the differences in stories as it is to see the patterns found in Campbell’s monomyth. You should do the same for the rest of the stories in this unit. As you read the stories, try to see which stages are represented and which aren’t.

The Monomyth: Not Just for Mythology

Earlier we mentioned that the popularity of the monomyth is not so much in the fantastical aspects. The real reason why ordinary humans like ourselves love these kinds of outlandish storylines is that we want to strive to be heroes ourselves. We might not be slaying monsters, but human life involves facing and defeating obstacles all around us. We sympathize with a hero in trouble, suffering, doubting his abilities, because we know this kind of struggle personally. We are the heroes in the story of our lives. Think of yourself– as an international student, as an immigrant in a strange land, the struggles, the victories, the obstacles, the sacrifices, the losses you have experienced, how all of those experiences have transformed you, and the ultimate goal you are working towards.

Not only has the monomyth inspired stories for generations, but it has inspired other fields. Some self-help books encourage people to look at their own hero’s journey as a kind of therapy and encouragement. The stages of the hero’s journey have been used to encourage entrepreneurs starting their own businesses–the risks it might entail, and what to do when facing difficult situations. There is even a hero’s journey fitness program to help people lose weight and gain confidence, and a book for teachers–the heroes of strange lands called “the classroom.” Not only is the monomyth an interesting theory behind some of the most popular adventure stories on Earth, it is the story of life itself.

Comprehension Questions

Answer the following questions based on the article about the hero’s journey.

- Give a short paragraph summary (no more than 5 sentences) of the hero’s journey.

- Why has the monomyth stayed popular for thousands of years?

This chart will be used often to focus on how each of the adventure stories we read follows Campbell’s idea of the “hero’s journey”. Summarize the steps in the hero’s journey in the chart below.

| Step in the hero’s journey | summary of step |

|---|---|

| 1. Special birth/humble upbringing | |

| 2. Ordinary world | |

| 3. Call to adventure | |

| 4. Refusal of the call | |

| 5. Supernatural aid/mentor & Talisman | |

| 6. Crossing the threshold | |

| 7. 1st battle: threshold guardians | |

| 8. Allies | |

| 9. Road of trials | |

| 10. Meeting with the goddess/temptress | |

| 11. Father/brother battle | |

| 12. Apotheosis | |

| 13. The ultimate reward | |

| 14. Refusal to return | |

| 15. Magical Flight / Rescue from without | |

| 16. Crossing the return threshold | |

| 17. Master of two worlds | |

| 18. Freedom to live |

CEFR Level: CEF Level B2