6.1: What is Culture?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 115947

- Jason S. Wrench, Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter & Katherine S. Thweatt

- SUNY New Paltz & SUNY Oswego via OpenSUNY

Learning Outcomes

- Define the term “culture” as it is used within this book.

- Understand a dominant culture.

- Differentiate between a co-culture and a microculture.

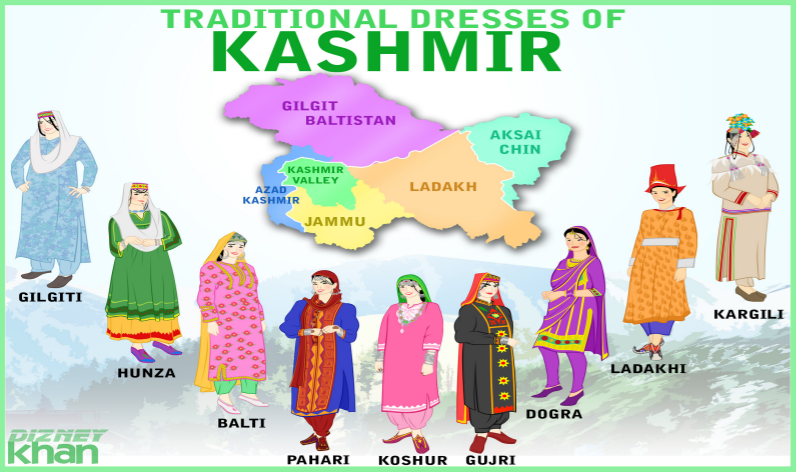

When people hear the word “culture,” many different images often come to mind. Maybe you immediately think of going to the ballet, an opera, or an art museum. Other people think of traditional dress like that seen from Kashmir in Figure 6.1.1. However, the word “culture” has a wide range of different meanings to a lot of different people. For example, when you travel to a new country (or even a state within your own country), you expect to encounter different clothing, languages, foods, rituals, etc.… The word “culture” is a hotly debated term among academics. In 1952, A. L. Kroeber and Clyde Kluckhohn compiled a list of 164 definitions for the word “culture.” Culture is often described as “the way we do things.”1 In their book, the authors noted, “Considering that concept [of culture] has had a name for less than 80 years, it is not surprising that full agreement and precision has not yet been attained.” 2 Kroeber and Kluckhohn predicted that eventually, science would land on a singular definition of culture as it was refined through the scientific process over time. Unfortunately, the idea of a single definition of culture is no closer to becoming a reality today than it was in 1952.3

For our purposes, we are going to talk about culture as “a group of people who through a process of learning are able to share perceptions of the world which influences their beliefs, values, norms, and rules, which eventually affect behavior.”4 Let’s break down this definition. First, when we talk about “culture,” we are starting off with a group of people. One of the biggest misunderstandings new people studying culture have is that an individual can have their own personalized culture. Culture is something that is formed by the groups that we grow up in and are involved with through our lifetimes.

Second, we learn about our culture. In fact, culture becomes such an ingrained part of who we are that we often do not even recognize our own culture and how our own culture affects us daily. Just like language, everyone is hardwired to learn culture. What culture we pick up is ultimately a matter of the group(s) we are born into and raised. Just like a baby born to an English-speaking family isn’t going to magically start speaking French out of nowhere, neither will a person from one culture adopt another culture accidentally.

Third, what we learn ultimately leads to a shared perception of the world. All cultures have stories that are taught to children that impact how they view the world. If you are raised by Jewish or Christian parents/guardians, you will learn the creation story in the Bible. However, this is only one of many different creation myths that have abounded over time in different cultures:

- The Akamba in Kenya say that the first two people were lowered to earth by God on a cloud.

- In ancient Babylon and Sumeria, the gods slaughtered another god named We-ila, and out of his blood and clay, they formed humans.

- One myth among the Tibetan people is that they owe their existence to the union of an ogress, not of this world, and a monkey on Gangpo Ri Mountain at Tsetang.

- And the Aboriginal tribes in Australia believe that humans are just the decedents of gods.5

Ultimately, which creation story we grew up with was a matter of the culture in which we were raised. These different myths lead to very different views of the individual’s relationship with both the world and with their God, gods, or goddesses.

Fourth, the culture we are raised in will teach us our beliefs, values, norms, and rules. Beliefs are assumptions and convictions held by an individual, group, or culture about the truth or existence of something. For example, in all of the creation myths discussed in the previous paragraph, these are beliefs that were held by many people at various times in human history. Next, we have values, or important and lasting principles or standards held by a culture about desirable and appropriate courses of action or outcomes. This definition is a bit complex, so let’s break it down. When looking at this definition, it’s important first to highlight that different cultures have different perceptions related to both courses of action or outcomes. For example, in many cultures throughout history, martyrdom (dying for one’s cause) has been something deeply valued. As such, in those cultures, putting one’s self in harm’s way (course of action) or dying (outcome) would be seen as both desirable and appropriate. Within a given culture, there are generally guiding principles and standards that help determine what is desirable and appropriate. In fact, many religious texts describe martyrdom as a holy calling. So, within these cultures, martyrdom is something that is valued. Next, within the definition of culture are the concepts of norms and rules. Norms are informal guidelines about what is acceptable or proper social behavior within a specific culture. Rules, on the other hand, are the explicit guidelines (generally written down) that govern acceptable or proper social behavior within a specific culture. With rules, we have clearly concrete and explicitly communicated ways of behaving, whereas norms are generally not concrete, nor are they explicitly communicated. We generally do not know a norm exists within a given culture unless we violate the norm or watch someone else violating the norm. The final part of the definition of culture, and probably the most important for our purposes, looking at interpersonal communication, is that these beliefs, values, norms, and rules will govern how people behave.

Co-cultures

In addition to a dominant culture, most societies have various co-cultures—regional, economic, social, religious, ethnic, and other cultural groups that exert influence in society. Other co-cultures develop among people who share specific beliefs, ideologies, or life experiences. For example, within the United States we commonly refer to a wide variety of different cultures: Amish culture, African American culture, Buddhist Culture, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA+) culture. With all of these different cultural groups, we must realize that just because individuals belong to a cultural group, that does not mean that they are all identical. For example, African Americans in New York City are culturally distinct from those living in Birmingham, Alabama, because they also belong to different geographical co-cultures. Within the LGBTQIA culture, the members who make up the different letters can have a wide range of differing cultural experiences within the larger coculture itself. As such, we must always be careful to avoid generalizing about individuals because of the co-cultures they belong to.

Co-cultures bring their unique sense of history and purpose within a larger culture. Co-cultures will also have their holidays and traditions. For example, one popular co-cultural holiday celebrated in the United States is Cinco de Mayo. Many U.S. citizens think that Cinco de Mayo is a Mexican holiday. However, this is not a Mexican holiday. Outside of Puebla, Mexico, it’s considered a relatively minor holiday even though children do get the day off from school. One big mistake many U.S. citizens make is assuming Cinco de Mayo is Mexican Independence Day, which it is not. Instead, El Grito de la Indepedencia (The Cry of Independence) is held annually on September 16 in honor of Mexican Independence from Spain in 1810. Sadly, Cinco de Mayo has become more of an American holiday than it is a Mexican one. Just as an FYI, Cinco de Mayo is the date (May 5, 1862) observed to commemorate the Mexican Army’s victory over the French Empire at the Battle of Puebla that conclude the Franco-Mexican War (also referred to as the Battle of Puebla Day). We raise this example because often the larger culture coopts parts of a co-culture and tries to adapt it into the mainstream. During this process, the meaning associated with the co-culture is often twisted or forgotten. If you need another example, just think of St. Patrick’s Day, which evolved from a religious celebration marking the death of St. Patrick on March 17, 461 CE, to a day when “everyone’s Irish” and drinks green beer.

Microcultures

The last major term we need to explain with regards to culture is what is known as a microculture. A microculture, sometimes called a local culture, refers to cultural patterns of behavior influenced by cultural beliefs, values, norms, and rules based on a specific locality or within an organization. “Members of a microculture will usually share much of what they know with everyone in the greater society but will possess a special cultural knowledge that is unique to the subgroup.”6 If you’re a college student and you’ve ever lived in a dorm, you may have experienced what we mean by a microculture. It’s not uncommon for different dorms on campus to develop their own unique cultures that are distinct from other dorms. They may have their own exclusive stories, histories, mascots, and specializations. Maybe you live in a dorm that specializes in honor’s students or pairs U.S. students with international students. Perhaps you live in a dorm that is allegedly haunted. Maybe you live in a dorm that values competition against other dorms on campus, or one that doesn’t care about the competition at all. All of these examples help individual dorms develop unique cultural identities.

We often refer to microcultures as “local cultures” because they do tend to exist among a small segment of people within a specific geographical location. There’s quite a bit of research on the topic of classrooms as microcultures. Depending on the students and the teacher, you could end up with radically different classroom environments, even if the content is the same. The importance of microcultures goes back to Abraham Maslow’s need for belonging. We all feel the need to belong, and these microcultures give us that sense of belonging on a more localized level.

For this reason, we often also examine microcultures that can exist in organizational settings. One common microculture that has been discussed and researched is the Disney microculture. Employees (oops! We mean cast members) who work for the Disney company quickly realize that there is more to working at Disney than a uniform and a name badge. Disney cast members do not wear uniforms; everyone is in costume. When a Disney cast member is interacting with the public, then they are “on stage;” when a cast member is on a break away from the public eye, then they are “backstage.” From the moment a Disney cast member is hired, they are required to take Traditions One and probably Traditions Two at Disney University, which is run by the Disney Institute (http://disneyinstitute.com/). Here is how Disney explains the purpose of Traditions: “Disney Traditions is your first day of work filled with the History & Heritage of The Walt Disney Company, and a sprinkle of pixie dust!”7 As you can tell, from the very beginning of the Disney cast member experience, Disney attempts to create a very specific microculture that is based on all things Disney.

Key Takeaways

- Over the years, there have been numerous definitions of the word culture. As such, narrowing down to only one definition of the term is problematic, no matter how you define “culture.” For our purposes, we define culture as a group of people who, through a process of learning, can share perceptions of the world, which influences their beliefs, values, norms, and rules, which eventually affect behavior.

- In the realm of cultural studies, we discuss three different culturally related terms. First, we have a dominant culture, or the established language, religion, behavior, values, rituals, and social customs of a specific society. Within that dominant culture will exist numerous co-cultures and microcultures. A co-culture is a regional, economic, social, religious, ethnic, or other cultural groups that exerts influence in society. Lastly, we have microcultures or cultural patterns of behavior influenced by cultural beliefs, values, norms, and rules based on a specific locality or within an organization.

Exercises

- Think about your own dominant culture. What does it mean to be a member of your national culture? What are the established language, religion, behavior, values, rituals, and social customs within your society?

- Make a list of five co-cultural groups that you currently belong to. How does each of these different co-cultural groups influence who you are as a person?

- Many organizations are known for creating, or attempting to create, very specific microcultures. Thinking about your college or university, how would you explain your microculture to someone unfamiliar with your culture?