7.4: Hearing

- Page ID

- 173138

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Hearing

- Label key structures of the ear, identify their functions, and describe the role they play in hearing.

- Explain how we encode and perceive pitch.

- Explain how we localize sound.

- Describe how hearing and the vestibular system are associated.

Overview

The perception of sound is critical for the survival of many species. Although it is clearly possible for humans with hearing limitations to function and thrive, it is definitely one of the most important senses in terms of navigating our world and communicating with others. This text uses vision as a model system to illustrate the wonder and complexities of sensation and perception. Hence, a more detailed treatment of all aspects of visual processing was presented. The remaining senses will be presented with a more general exploration of their sensation and perception processes. This section will provide an overview of the basic anatomy and function of the auditory system, how we perceive pitch, and how we know where sound is coming from.

Auditory Processing and the Ear

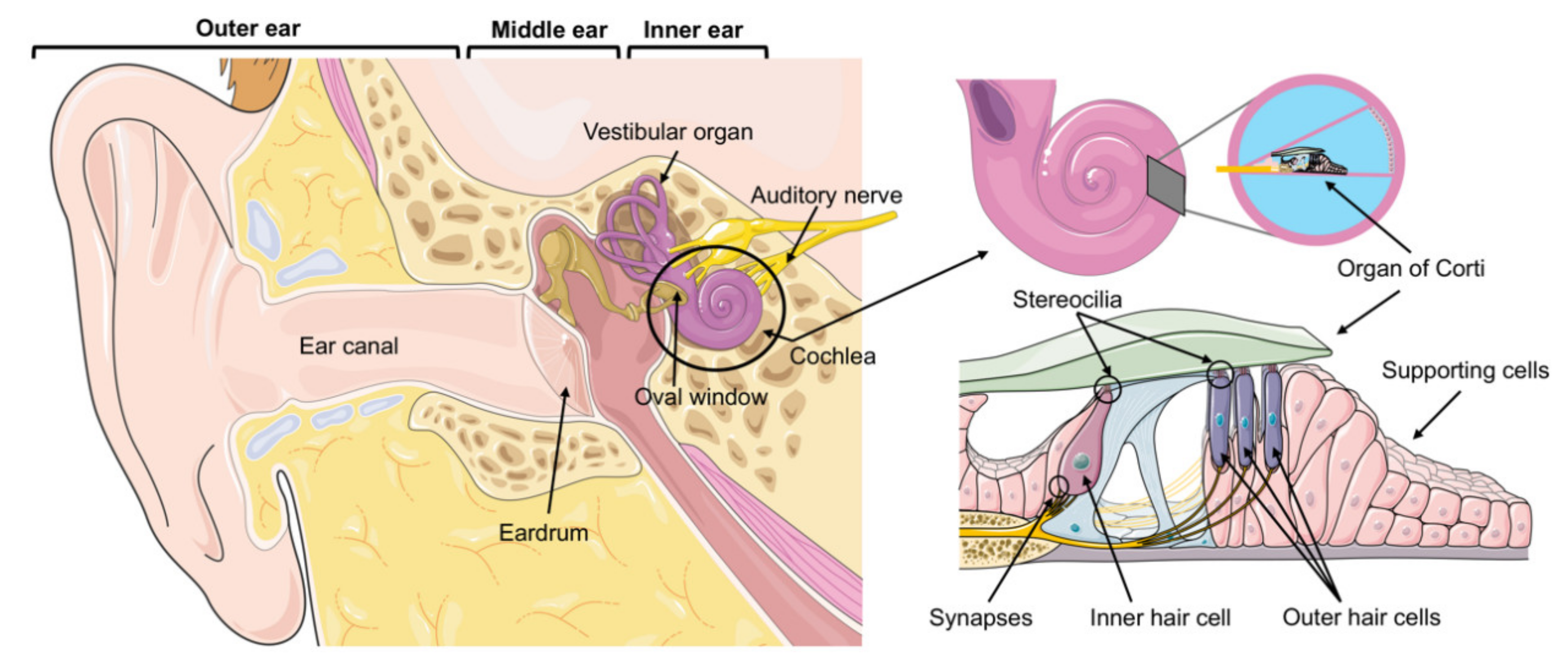

It has been argued that humans can hear a variety of sounds and distinguish between a large variation of them. This ability begins with the unique architecture of the accessory structure for hearing, the ear. The complex anatomy of the ear in humans can be divided into three sections. As detailed in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) (Left), these sections include the external, middle, and inner ear. With the exception of the final component of the inner ear, these three sections are all part of the non-neural accessory structure for hearing. Just like with other senses, these accessory structures act to convert and transfer the incoming environmental stimuli into something that the specialized receptor cells can respond to. Some parts of this accessory apparatus, such as the small bones of the middle ear are particularly delicate and prone to deficits that can lead to hearing loss.

The environmental stimuli for hearing are basically air vibrations. Unlike light waves which travel in a vacuum, these air disturbances or "sound waves" are transferred when molecules bump into each other in the air and, if the waves are of high enough amplitude result in our ultimate perception of them. However, before we get close to perception, these waves must first make their way through the outer and middle ear before reaching the "sensation" step which occurs in the cochlea of the inner ear.

The specialized, sensory receptor cells for audition are located along the basilar membrane in the middle of three, fluid-filled canals of the cochlea. These cells are called auditory hair cells due to the cilia or hair-like structure of their dendrites. See Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) (Right). When the dendrites or cilia of these cells move they produce electrical changes or impulses which then travel along the auditory nerve into the brain. Ultimately, this activity reaches the primary auditory cortex and beyond to produce perception.

The illustration below summarizes the complex system of the ear and how the anatomical structures and connections between them lead to the ability to perceive the sounds of nature, appreciate beauty of music and utilize language to communicate with others who speak the same language (see Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) – Accessory Structures of the Ear (Left): The Outer ear contains the external pinna (not labelled), ear canal, and tympanic membrane ("eardrum"). The Middle ear contains three small bones called ossicles . The Inner ear contains the cochlea. Neural Component - Organ of Corti (Right): The spiral-shaped cochlea is the auditory sensory organ where mechanical sound waves are transmitted into electrical signals by the hair cells of the organ of Corti. See the text for further details. The figure was created with Servier Medical Art templates by Servier, which are licensed under a CC BY 3.0; https://smart.servier.com (accessed on 16 January 2021). See Cortada, et al. (2021)

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) – Accessory Structures of the Ear (Left): The Outer ear contains the external pinna (not labelled), ear canal, and tympanic membrane ("eardrum"). The Middle ear contains three small bones called ossicles . The Inner ear contains the cochlea. Neural Component - Organ of Corti (Right): The spiral-shaped cochlea is the auditory sensory organ where mechanical sound waves are transmitted into electrical signals by the hair cells of the organ of Corti. See the text for further details. The figure was created with Servier Medical Art templates by Servier, which are licensed under a CC BY 3.0; https://smart.servier.com (accessed on 16 January 2021). See Cortada, et al. (2021)Theories of Auditory Perception

The incoming sound waves come in different frequencies, with low frequency sounds ultimately being perceived as lower pitched and higher frequency sounds being perceived as higher pitched. In particular, the human ear is most responsive to sounds that are in the same frequency as the human voice. This is why parents and mothers in particular are able to pick out the sound of their children’s voice amongst other children’s voices and we are often able to identify another person from the sound of their voice without having to see them physically. The complex system of the ear allows us to process sounds almost instantly.

There are a few theories that have been proposed to help account as to why individuals can distinguish between pitch perception and frequencies. Two commonly accepted ones are detailed here.

The temporal theory of pitch perception asserts that frequency is coded by the differential activity level of individual sensory neurons. This would mean that a given hair cell would fire action potentials related to the frequency of the sound wave. While this is a very intuitive explanation, we detect such a broad range of frequencies (20–20,000 Hz) that the frequency of action potentials fired by hair cells cannot account for the entire range. Because of properties related to sodium channels on the neuronal membrane that are involved in action potentials, there is a point at which a cell cannot fire any faster (Shamma, 2001).

The place theory of pitch perception suggests that different portions of the basilar membrane moves up and down in response to incoming sound waves. More specifically, the base of the basilar membrane responds best to high frequencies and the tip of the basilar membrane responds best to low frequencies. Therefore, hair cells that are in the base portion would be labeled as high-pitch receptors, while those in the tip of basilar membrane would be labeled as low-pitch receptors (Shamma, 2001). In reality, both theories explain different aspects of pitch perception. At frequencies up to about 4000 Hz, it is clear that both the rate of action potentials and place contribute to our perception of pitch. However, much higher frequency sounds can only be encoded using place cues (Shamma, 2001).

Sound Localization

Similar to the need for recognizing different pitches and frequencies, knowing where particular sounds are coming from (sound localization) is an important part of navigating the environment around us. The auditory system has the ability to use monaural (one ear) and binaural (two ears) cues to locate where a particular sound might be coming from. Each pinna interacts with incoming sound waves differently, depending on the sound’s source relative to our bodies. This interaction provides a monaural cue that is helpful in locating sounds that occur above or below and in front or behind us. The sound waves received by your two ears from sounds that come from directly above, below, in front, or behind you would be identical; therefore, monaural cues are essential (Grothe, Pecka, & McAlpine, 2010).

Binaural cues, on the other hand, provide information on the location of a sound along a horizontal axis by relying on differences in patterns of vibration of the eardrum between our two ears. If a sound comes from an off-center location, it creates two types of binaural cues: interaural level differences and interaural timing differences. Interaural level difference refers to the fact that a sound coming from the right side of your body is more intense at your right ear than at your left ear because of the attenuation of the sound wave as it passes through your head. Interaural timing difference refers to the small difference in the time at which a given sound wave arrives at each ear, illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\). Certain brain areas monitor these differences to construct where along a horizontal axis a sound originates (Grothe et al., 2010).

Hearing Loss

- About 2 to 3 out of every 1,000 children in the United States are born with a detectable level of hearing loss in one or both ears (https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/sta...istics-hearing).

- More than 90 percent of deaf children are born to hearing parents (https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/sta...istics-hearing).

- Approximately 15% of American adults (37.5 million) aged 18 and over report some trouble hearing (https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/sta...istics-hearing)

Conductive hearing loss can be caused by physical damage to the ear (such as to the eardrums); this condition reduces the ability of the ear to transfer vibrations from the outer ear to the inner ear. Conductive hearing loss can also be a result of fusion of the ossicles (three bones in the middle ear). Sensorineural hearing loss, which is caused by damage to the cilia (of the hair cells) or to the auditory nerve, is not as common as conductive hearing loss but the likelihood of this condition increases with age (Tennesen, 2007). As we continue to get older damage to the cilia increases; by the age of 65 years old 40% of individuals will have had damage to the cilia (Chisolm, Willott, & Lister, 2003).

Individuals who have experienced sensorineural hearing loss may benefit from a cochlear implant. Data From the National Institutes of Health shows that as of December 2019, approximately 736,900 cochlear implants have been implanted worldwide. In the United States, roughly 118,100 devices have been implanted in adults and 65,000 in children The following video explains the process of a cochlear implant.

Deafness and Deaf Culture

In most modern nations people who are born or become deaf at an early age have developed their own system of communication and culture amongst themselves and people close to them. It has been argued that encouraging deaf people to sign is a more appropriate adjustment as opposed to encouraging them to speak, read lips or have cochlear implant surgeries. However, more recent studies suggest that due to advancements in technology, cochlear implants increase the likelihood of a person being able to have and engage in some auditory and speaking activities if implanted early enough (Dettman, Pinder, Briggs, Dowell, & Leigh, 2007; Dorman & Wilson, 2004). As a result parents often face the difficult decision of whether to take advantage of new technologies and approaches of providing support to deaf students in mainstream classroom settings or utilizing American Sign Language (ASL) schools and encouraging more immersion in those settings.

Hearing and the Vestibular System

The vestibular system has some similarities with the auditory system. It utilizes hair cells just like the auditory system, but it excites them in different ways. There are five vestibular receptor organs in the inner ear: the utricle, the saccule, and three semicircular canals. Together, they make up what’s known as the vestibular labyrinth that is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). The utricle and saccule respond to acceleration in a straight line, such as gravity. The roughly 30,000 hair cells in the utricle and 16,000 hair cells in the saccule lie below a gelatinous layer, with their stereocilia projecting into the gelatin. Embedded in this gelatin are calcium carbonate crystals—like tiny rocks. When the head is tilted, the crystals continue to be pulled straight down by gravity, but the new angle of the head causes the gelatin to shift, thereby bending the stereocilia. The bending of the stereocilia stimulates the neurons, and they signal to the brain that the head is tilted, allowing the maintenance of balance. It is the vestibular branch of the vestibulocochlear cranial nerve that deals with balance.

Attributions

- Hearing sections adapted by Isaias Hernandez from "Anatomy and Physiology from Oregon State University"; https://open.oregonstate.education/a.../15-3-hearing/

- Hearing sections adapted by Isaias Hernandez from "Psychology 2e from OpenStax"; https://openstax.org/books/psycholog...es/5-4-hearing

References

Cortada, M., Levano, S., & Bodmer, D. (2021). mTOR Signaling in the Inner Ear as Potential Target to Treat Hearing Loss. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(12), 6368. MDPI AG. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijms22126368