Chapter Summary: The first half of this chapter attempts to define music as a subject and offers perspectives on music, including basic vocabulary and what you should know about music in order to incorporate it in your work with children. The second half gives a brief overview of music education and teaching in the U.S., which provides the foundation of the discipline for the book.

I. Defining Music

“Music” is one of the most difficult terms to define, partially because beliefs about music have changed dramatically over time just in Western culture alone. If we look at music in different parts of the world, we find even more variations and ideas about what music is. Definitions range from practical and theoretical (the Greeks, for example, defined music as “tones ordered horizontally as melodies and vertically as harmony”) to quite philosophical (according to philosopher Jacques Attali, music is a sonoric event between noise and silence, and according to Heidegger, music is something in which truth has set itself to work). There are also the social aspects of music to consider. As musicologist Charles Seeger notes, “Music is a system of communication involving structured sounds produced by members of a community that communicate with other members” (1992, p.89). Ethnomusicologist John Blacking declares that “we can go further to say that music is sound that is humanly patterned or organized” (1973), covering all of the bases with a very broad stroke. Some theorists even believe that there can be no universal definition of music because it is so culturally specific.

Although we may find it hard to imagine, many cultures, such as those found in the countries of Africa or among some indigenous groups, don’t have a word for music. Instead, the relationship of music and dance to everyday life is so close that the people have no need to conceptually separate the two. According to the ethnomusicologist Bruno Nettl (2001), some North American Indian languages have no word for “music” as distinct from the word “song.” Flute melodies too are labeled as “songs.” The Hausa people of Nigeria have an extraordinarily rich vocabulary for discourse about music, but no single word for music. The Basongye of Zaire have a broad conception of what music is, but no corresponding term. To the Basongye, music is a purely and specifically human product. For them, when you are content, you sing, and when you are angry, you make noise (2001). The Kpelle people of Liberia have one word, “sang,” to describe a movement that is danced well (Stone, 1998, p. 7). Some cultures favor certain aspects of music. Indian classical music, for example, does not contain harmony, but only the three textures of a melody, rhythm, and a drone. However, Indian musicians more than make up for a lack of harmony with complex melodies and rhythms not possible in the West due to the inclusion of harmony (chord progressions), which require less complex melodies and rhythms.

What we may hear as music in the West may not be music to others. For example, if we hear the Qur’an performed, it may sound like singing and music. We hear all of the “parts” which we think of as music—rhythm, pitch, melody, form, etc. However, the Muslim understanding of that sound is that it is really heightened speech or recitation rather than music, and belongs in a separate category. The philosophical reasoning behind this is complex: in Muslim tradition, the idea of music as entertainment is looked upon as degrading; therefore, the holy Qur’an cannot be labeled as music.

Activity 2A

Listen

Qur’an Recitation, 22nd Surah (Chapter) of the Qur’an, recited by Mishary Rashid Al-‘Efasi of Kuwait.

Although the exact definition of music varies widely even in the West, music contains melody, harmony, rhythm, timbre, pitch, silence, and form or structure. What we know about music so far…

- Music is comprised of sound.

- Music is made up of both sounds and silences.

- Music is intentionally made art.

- Music is humanly organized sound (Bakan, 2011).

A working definition of music for our purposes might be as follows: music is an intentionally organized art form whose medium is sound and silence, with core elements of pitch (melody and harmony), rhythm (meter, tempo, and articulation), dynamics, and the qualities of timbre and texture.

Beyond a standard definition of music, there are behavioral and cultural aspects to consider. As Titon notes in his seminal text Worlds of Music (2008), we “make” music in two different ways: we make music physically; i.e., we bow the strings of a violin, we sing, we press down the keys of a piano, we blow air into a flute. We also make music with our minds, mentally constructing the ideas that we have about music and what we believe about music; i.e., when it should be performed or what music is “good” and what music is “bad.” For example, the genre of classical music is perceived to have a higher social status than popular music; a rock band’s lead singer is more valued than the drummer; early blues and rock was considered “evil” and negatively influential; we label some songs as children’s songs and deem them inappropriate to sing after a certain age; etc.

Music, above all, works in sound and time. It is a sonic event—a communication just like speech, which requires us to listen, process, and respond. To that end, it is a part of a continuum of how we hear all sounds including noise, speech, and silence. Where are the boundaries between noise and music? Between noise and speech? How does some music, such as rap, challenge our original notions of speech and music by integrating speech as part of the music? How do some compositions such as John Cage’s 4’33’’ challenge our ideas of artistic intention, music, and silence?

read more John Cage 4’33’’

watch this Annenberg Video: Exploring the world of music

Activity 2B

Imagine the audience’s reaction as they experience Cage’s 4’33” for the first time. How might they react after 15 seconds? 30? One minute?

Basic Music Elements

- Sound (overtone, timbre, pitch, amplitude, duration)

- Melody

- Harmony

- Rhythm

- Texture

- Structure/form

- Expression (dynamics, tempo, articulation)

In order to teach something, we need a consensus on a basic list of elements and definitions. This list comprises the basic elements of music as we understand them in Western culture.

1. Sound

Overtone: A fundamental pitch with resultant pitches sounding above it according to the overtone series. Overtones are what give each note its unique sound.

watch this throat-singing

Timbre: The tone color of a sound resulting from the overtones. Each voice has a unique tone color that is described using adjectives or metaphors such as “nasally,” “resonant,” “vibrant,” “strident,” “high,” “low,” “breathy,” “piercing,” “ringing,” “rounded,” “warm,” “mellow,” “dark,” “bright,” “heavy,” “light,” “vibrato.”

Pitch: The frequency of the note’s vibration (note names C, D, E, etc.).

Amplitude: How loud or soft a sound is.

Duration: How long or short the sound is.

2. Melody

A succession of musical notes; a series of pitches often organized into phrases.

3. Harmony

The simultaneous, vertical combination of notes, usually forming chords.

4. Rhythm

The organization of music in time. Also closely related to meter.

5. Texture

The density (thickness or thinness) of layers of sounds, melodies, and rhythms in a piece: e.g., a complex orchestral composition will have more possibilities for dense textures than a song accompanied only by guitar or piano.

Most common types of texture:

- Monophony: A single layer of sound; e.g.. a solo voice

- Homophony: A melody with an accompaniment; e.g., a lead singer and a band; a singer and a guitar or piano accompaniment; etc.

- Polyphony: Two or more independent voices; e.g., a round or fugue.

watch this Musical Texture

6. Structure or Form

The sections or movements of a piece; i.e. verse and refrain, sonata form, ABA, Rondo (ABACADA), theme, and variations.

7. Expression

Dynamics: Volume (amplitude)—how loud, soft, medium, gradually getting louder or softer (crescendo, decrescendo).

Tempo: Beats per minute; how fast, medium, or slow a piece of music is played or sung.

Articulation: The manner in which notes are played or words pronounced: e.g., long or short, stressed or unstressed such as short (staccato), smooth (legato), stressed (marcato), sudden emphasis (sforzando), slurred, etc.

What Do Children Hear? How Do They Respond to Music?

Now that we have a list of definitions, for our purposes, let’s refine the definition of music, keeping in mind how children perceive music and music’s constituent elements of sound (timbre), melody, harmony, rhythm, structure or form, expression, and texture. Children’s musical encounters can be self- or peer-initiated, or teacher- or staff-initiated in a classroom or daycare setting. Regardless of the type of encounter, the basic music elements play a significant role in how children respond to music. One of the most important elements for all humans is the timbre of a sound. Recognizing a sound’s timbre is significant to humans in that it helps us to distinguish the source of the sound, i.e. who is calling us—our parents, friends, etc. It also alerts us to possible danger. Children are able to discern the timbre of a sound from a very young age, including the vocal timbres of peers, relatives, and teachers, as well as the timbres of different instruments.

Studies show that even very young children are quite sophisticated listeners. As early as two years of age, children respond to musical style, tempo, and dynamics, and even show preference for certain musical styles (e.g., pop music over classical) beginning at age five. Metz and his peers assert that “a common competence found in young children is the enacting through movement of the music’s most constant and salient features, such as dynamics, meter, and tempo” (Metz, 1989; Gorali-Turel, 1997; Chen-Hafteck, 2004). On the aggregate level, children physically respond to music’s beat, and are able to move more accurately when the tempo of the music more clearly corresponds to the natural tempo of the child. As we might expect, children respond to the dynamic levels of loud and soft quite dramatically, changing their movements to match changing volume levels.

The fact that children seem to respond to the expressive elements of music (dynamics, tempo, etc.) should not come as a surprise. Most people respond to the same attributes of music that children do. We hear changes in tempo (fast or slow), changes in dynamics (loud or soft), we physically respond to the rhythm of the bass guitar or drums, and we listen intently to the melody, particularly if there are words. These are among the most ear-catching elements, along with rhythm and melody.

This is what we would expect. However, there are other studies whose conclusions are more vague on this subject. According to a study by Sims and Cassidy, children’s music attitudes and responses do not seem to be based on specific musical characteristics and children may have very idiosyncratic responses and listening styles (1997). Mainly, children are non-discriminating, reacting positively to almost any type of music (Kim, 2007, p. 23).

Activity 2C

What type of music might children best respond to given their musical perceptions and inclinations? Is there a particular genre of music, or particular song or set of songs? How might you get them to respond actively while engaging a high level of cognitive sophistication?

Music Teaching Vocabulary

After familiarizing yourself with the basic music vocabulary list above (e.g., melody, rhythm), familiarize yourself with a practical teaching vocabulary: in other words, the music terms that you might use when working in music with a lesson for children that correspond to their natural perception of music. For most children, the basics are easily conveyed through concept dichotomies, such as:

- Fast or Slow (tempo)

- Loud or Soft (dynamics)

- Short or Long (articulation)

- High or Low (pitch)

- Steady or Uneven (beat)

- Happy or Sad (emotional response)

Interestingly, three pairs of these dichotomies are found in Lowell Mason’s Manual for the Boston Academy of Music (1839).

For slightly older children, more advanced concepts can be used, such as:

- Duple (2) or Triple (3) meter

- Melodic Contour (melody going up or down)

- Rough or Smooth (timbre)

- Verse and Refrain (form)

- Major or Minor (scale)

Music Fundamentals

The emotive aspects of music are what most people respond to first. However, while an important part of music listening in our culture, simply responding subjectively to “how music makes you feel” is similar to an Olympic judge saying that she feels happy when watching a gymnast’s vault. It may very well be true, but it does not help the judge to understand and evaluate all of the elements that go into the execution of the gymnast’s exercise or how to judge it properly. Studies show that teachers who are familiar with music fundamentals, and especially note reading, are more comfortable incorporating music when working with children (Kim, 2007). Even just knowing how to read music changes a teacher’s confidence level when it comes to singing, so it’s important to have a few of the basics under your belt.

II. Music Education in America

Music education does not exist isolated in the music classroom. It is influenced by trends in general education, society, culture, and politics.

—Harold Abeles, Critical Issues in Music Education, 2010

How did music education develop into its current form? Did music specialists always teach music? What were classroom teacher’s musical responsibilities? Well, to answer these questions, we need to look to the past for a moment. Initially, music and education worked hand in hand for centuries.

Early Music Teaching

18th century: Singing schools and their tune books

Before there was formal music education in the United States, there was music and education, primarily experienced through religious education. Music education in the U.S. began after the Pilgrims and Puritans arrived, when ministers realized that their congregation needed help singing and reading music. Several ministers developed tune books that used four notes of solfege (Mi, Fa, Sol, La) and shape notes to train people in singing the psalms and hymns required for proper church singing. By 1830, singing schools based on the techniques found in these books began popping up all over New England, with some people attending singing school classes every day (Keene, 1982). They were promised that they would learn to sing in a month or become music teachers themselves in three months.

Some consider the hymn music of this time to be uniquely American—borrowing styles from Ireland, England, and Europe, but using dance rhythms, loose harmonic rules, and complex vocal parts (counterpoint) where each voice (soprano, alto, tenor and bass) sang its own unique melody and no one had the main melody. Original American composers such as William Billings wrote hundreds of hymns in this style.

19th century

Johann H. Pestalozzi (1746–1827)

Pestalozzi was an educational reformer and Swiss philosopher born in 1746. He is known as the father of modern education. Although his philosophies are over 200 years old, you may recognize his ideas as sounding quite contemporary. He believed in a child-centered education that promoted understanding the world from the child’s level, taking into account individual development and concrete, tactile experiences such as working directly with plants, minerals for science, etc. He advocated teaching poor as well as rich children, breaking down a subject to its elements, and a broad, liberal education along with teacher training. In the U.S., normal schools would take off by the end of the 19th century, and advocates of Pestalozzi’s educational reform would put into place a system of teacher training that influences us to this day.

Lowell Mason (1792–1872) and the “Better Music” movement

Lowell Mason, considered the founder of music education in America, was a proponent of Pestalozzi’s ideas, particularly the rote method of teaching music, where songs were experienced and repeated first and concepts were taught afterward. Mason authored the first series book based on the rote method in 1864 called The Song Garden.

Mason was highly critical of both the singing schools of the day and the compositional style. He was horrified at the promises that singing schools made to their students—namely that they could be qualified to teach after only a few months of lessons, and the general composition techniques used at the time. Mason felt that the music, including the work of composers such as Billings, was “rude and crude.” To change this, he promoted simplified harmonies that made the melody the most prominent aspect of the music, and downgraded the importance of the other vocal parts to support the melody. He accomplished this through the establishment of shape note singing schools, which carried out his musical vision. The result was that the original hymn style became the purview of the shape note singing schools, mostly in the South, where they flourished for many years. The most famous shape-note book is called Sacred Harp.

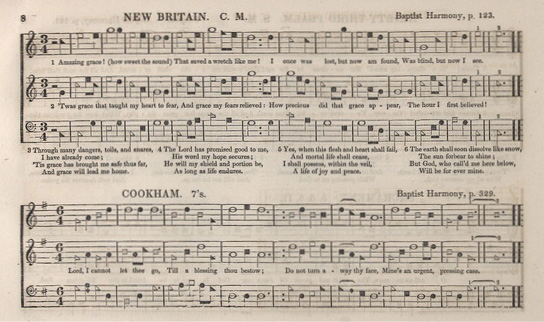

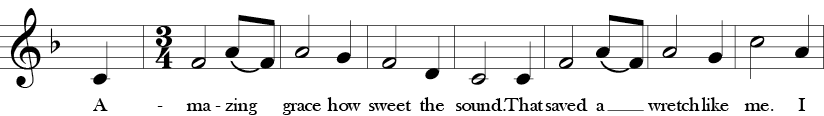

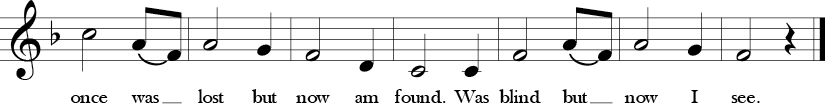

Hosted at the U.S. Library of Congress (U.S Library of Congress and [1]) [Public domain], via WikiCommons

Under the title “New Britain”, “Amazing Grace” appears in a 1847 publication of Southern Harmony in shape notes

The songs in Sacred Harp were religious hymns. “Amazing Grace” was one of the songs published in this book.

Amazing Grace

John Newton (1779), Sacred Harp Songbook (1844)

watch this Shape Note Singing

watch this Sacred Harp Shape Note Singing

read more Shape Notes

In 1833, Lowell Mason and others began to introduce the idea of music education in the schools. Mason, along with Thomas Hastings, went on to establish the first public school music program in Boston, beginning with the Boston Singing School, which taught children singing under his methodology. Eventually, regular classroom teachers were educated in normal schools (later called teachers’ colleges), developed in the mid-19th century, where they were taught the general subjects and were expected to teach the arts as well (Brown, 1919).

The up-to-date primary school, realizing the limitations of the 3 R’s curriculum, has enriched its program by adding such activities as singing, drawing, constructive occupations, story-telling, and games, and has endeavored to organize its work in terms of children rather than the subject matter (Temple, 1920, 499).

Music and the normal school

Normal schools in the 19th century grew out of a need to educate a burgeoning young American population. These schools were teacher preparation courses, usually with access to model schools where teachers in training could observe and practice teach. Music was a significant part of education. The Missouri State Normal School at Warrensburg stressed the importance of music in their catalog from 1873–74:

Vocal Music—the importance of music as one of the branches of education is fully recognized. Vocal music is taught throughout the entire course…and teachers are advised to make it a part of the course of instruction in every school with which they may be connected (Keene, 1982, p. 204).

Music and education in America: 20th century

Music supervisors, who oversaw the work of classroom teachers, received additional training in music. Music education in the early 20th century continued under the purview of the music supervisor, while classroom teachers were trained to teach music to their students. Gradually, a specialization process began to occur and music became a regular subject with its own certification, an educational tradition that continues to this day. By the 1920s, institutions in the U.S. began granting degrees in music education and, along with groups such as the Music Supervisor’s Conference (later the Music Educator’s National Conference and currently the National Association for Music Educators or NAfME), supported the use of qualified music teachers in the schools. Eventually, the arts broke into different specialties, and the separate role of music teacher as we know it was created.

Ironically, there was great concern at the time regarding these special music teachers. Because music was no longer in the hands of the classroom teachers, great effort was made to “bring music in as close a relation to the other work as is possible under the present arrangement of a special music teacher” (Goodrich, 1901, p. 133).

Contemporary Music Education

Instructional methods

The role of music in the U.S. educational system is perpetually under discussion. On one hand, many see structural problems inherent in music’s connection to its history and the glaring distinction between the prevalence, importance, and function of music’s role in everyday life and its embattled role in the classroom Sloboda (2001). On the other, increased advocacy is required in order to justify music’s existence and terms of benefits to the child amidst the threat of constant budget cuts. Given this, it is important to remember music education’s history, origin and deep roots in the American education experience.

The beginning of the 20th century was an exciting time for music education, with several significant instructional methods being developed and taking hold. In the United States, music education developed around a method of instruction, the Normal Music Course, the remnants of which are adhered to even today in music classrooms. The books used a “graded” curriculum with successively more complex songs and exercises, and combined author-composed songs in these books with folk and classical material. An online copy of the New Normal Music Course (1911) for fourth and fifth graders is accessible via Google Books.

In Europe and Asia, four outstanding and very different music instruction methods developed: the Kodály Method, Orff Schulwerk, Suzuki, and Dalcroze all played significant roles in furthering music education abroad and in the U.S., and were methods based on folk and classical genres (see Chapter 4 for further discussion about these methods). In contrast to the early music books for the Normal School, for which there was “a paucity of song material prompting the authors of the original course to chiefly use their own song material” (Tufts & Holt, 1911, p. 3), Kodály and Orff in particular used authentic music in their methods, and authentic music directly related to children’s lives (see Chapter 4 for more on this).

Resources

Gregory, A., Worrall, L., & Sarge, A. (1996). The development of emotional responses to music in young children. Motivation and Emotion. December 20 (4), 341–348.

Boone, R., & Cunningham, J. (2001). Children’s expression of emotional meaning in music through expressive body movement Journal of Non-verbal Behavior. March, 25 (1), 21–41.

- Children as young as four and five years old were able to portray emotional meaning in music through expressive movement.

Metz, E. R. (1989). Movement as a musical response among preschool children. Journal of Research in Music Education 37, 48–60.

- The primary result of “Movement as a Musical Response Among Preschool Children” was the generation of a substantive theory of children’s movement responses to music. The author also derived implications of the seven propositions of early children education and movement responses to music.

Sims, W., & Cassidy, J. (1997). Verbal and operant responses of young children to vocal versus instrumental song performances. Journal of Research in Music Education, 45(2), 234–244.

- Young children’s music attitudes and responses do not seem to be based on specific musical characteristics; children may have very idiosyncratic responses and listening styles.

References

Abeles, H. (2010). The historical contexts of music education. In H. Abeles & L. Custodero (Eds.), Critical issues in music education: Contemporary theory and practice (1–22). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Abeles, H., and Custodero, L. (2010). Critical issues in music education: Contemporary theory and practice. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Andress, B. (1991). From research to practice: Preschool children and their movement responses to music. Young Children, November, 22–27.

Atkinson, P., & Hammerley, M. (1994). Ethnography and participant observation. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (248–261), Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Attali, J. (1985). Noise: The Political Economy of Music. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Bakan, M. (2011). World music: Traditions and transformations. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Blacking, J. (1973). How Musical is Man? Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Boone, R. T., & Cunningham, J. G. (2001). Children’s expression of emotional meaning in music through expressive body movement. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 5(1), 21–41.

Bresler, L., & Stake, R. E. (1992). Qualitative research methodology in music education. In R. Colwell (Ed.), Handbook of research on music teaching and learning (75–90). New York: Schirmer Books.

Brown, H. A. (1919). The Normal School curriculum. The Elementary School Journal 20(4), 19, 276–284.

Chen-Hafteck, L. (2004). Music and movement from zero to three: A window to children’s musicality. In L. A. Custodero (Ed.), ISME Early Childhood Commission Conference—Els Móns Musicals dels Infants (The Musical Worlds of Children), July 5–10. Escola Superior de Musica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain. International Society of Music Education.

Cohen, V. (1980). The emergence of musical gestures in kindergarten children (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Illinois, Champaign, IL.

Flohr, J. W. (2005). The musical lives of young children. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice-Hall Music Education Series.

Goodrich, H. (1901). Music. The Elementary School Teacher and Course of Study, 2(2), 132–33.

Graue, M. E., & Walsh, D. J. (1998). Studying children in context: Theories, methods and ethics. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Heidegger, Martin. (2008). On the Origin of the Work of Art. In D. Farrell Krell (Ed.) Basic Writings (143-212). New York: Harper Collins

Holgersen, S. E., & Fink-Jensen, K. (2002). “The lived body—object and subject in research of music activities with preschool children.” Paper presented at the meeting of the10th International Conference of the Early Childhood Commission of the International Society for Music Education, August 5–9, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Janesick, V. J. (1994). The dance of qualitative research design: Metaphor, methodology, and meaning. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (209–219). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Jordan-DeCarbo, J., & Nelson, J. A. (2002). Music and early childhood education. In R. Colwell & C. Richardson (Eds.), The new handbook of research on music teaching and learning (210–242). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Keene, J. (1982). History of music education in the United States. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.

Kim, H. K. (2007). Early childhood preservice teachers’ beliefs about music, developmentally appropriate practice, and the relationship between music and developmentally appropriate practice (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

Mason, L. (1839). Manuel of the Boston Academy of Music for the instruction of vocal music in the system of Pestalozzi. Boston, MA: Wilkins and Carter.

Mason, L. (1866). The song garden. Boston, MA: Oliver Ditson and Co.

Metz, E. (1989). Movement as a musical response among preschool children. Journal of Research in Music Education 37(1), 48–60.

Moog, H. (1976). The musical experience of the pre-schoolchild. (C. Clarke, Trans.). London: Schott Music. (Original work published 1968)

Moorhead, G. E., & Pond, D. (1978). Music of young children: General observations. In Music of Young Children (29–64). Santa Barbara, California: Pillsbury Foundation for Advancement of Music Education. (Original work published 1942)

Nettl, B. (2001). Music. In S. Sadie (Ed.), New Grove dictionary of music and musicians (Vol. 17, 425-37) London: Grove’s Dictionaries of Music Inc.

Peery, J. C., & Peery, I. W. (1986). Effects of exposure to classical music on the musical preferences of pre-school children. Journal of Research in Music Education 33(1), 24–33.

Retra, J. (2005). Musical movement responses in early childhood music education practice in the Netherlands. Paper presented at the meeting of Music Educators and Researchers of Young Children (MERYC) Conference, April 4–5, at the University of Exeter.

Sims, W. L. (1987). The use of videotape in conjunction with systematic observation of children’s overt, physical responses to music: A research model for early childhood music education. ISME Yearbook 14, 63–67.

Sims, W. L., & Nolker, D. B. (2002). Individual differences in music listening responses of kindergarten children. Journal of Research in Music Education 50(2), 292–300.

Sloboda, J. (2001). Emotion, functionality and the everyday experience of music: Where does music education fit? Music Education Research 3(2).

Smithrim, K. (1994). Preschool children’s responses to music on television. Paper presented at the International Society for Music Education Early Childhood Commission Seminar “Vital Connections: Young Children, Adults & Music,” July 11–15, University of Missouri-Columbia.

Stone, R. (1998). Africa, the Garland encyclopedia of world music. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc..

Temple, A. (1920). The kindergarten primary unit. The Elementary School Journal, 20/7(20), 498–509.

The American singing movement. (2001). Smith Creek Music. www.smithcreekmusic.com/Hymnology/American.Hymnody/Singing.Schools/Singing.School.movement.html (accessed March 11, 2013).

Titon, J. T. (2008). Worlds of music: An introduction to the music of the world’s people. Boston, MA: Cengage.

Tobin, J. J., Wu, D. Y. H., & Davidson, D. H. (1989). Preschool in three cultures—Japan, China, and the United States. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Tufts, J., and Holt, H. (1911). The New Normal music course. Need location of publisher: Silver Burdett and Co.

Vocabulary

articulation: the manner in which notes are played or words pronounced; e.g., long or short, stressed or unstressed

counterpoint: the art of combining melodies

dynamics: indicates the volume of the sound, and the changes in volume (e.g. loudness, softness, crescendo, decrescendo).

harmony: the simultaneous combination of tones, especially when blended into chords pleasing to the ear; chordal structure, as distinguished from melody and rhythm

homophony: a melody with an accompaniment; e.g., a lead singer and a band

indigenous groups: people associated with a certain area who formulate their own culture

melody: musical sounds in agreeable succession or arrangement

meter: the organization of strong and weak beats; unit of measurement in terms of number of beats in a measure

monophony: single layer or sound; e.g.; a soloist

notation: how notes are written on the page

pitch: the frequency of a note’s vibration

polyphony: two or more independent voices; e.g., a round of a fugue

psalms and hymns: examples of church music

recitation: reading a text using heightened speech, similar to chanting

rhythm: the pattern of regular or irregular pulses caused in music by the occurrences of strong or weak melodic and harmonic beats

rote method: memorization technique based on repetition, especially when material is to be learned quickly

shape notes: notation style used in early singing schools in the U.S. where each note had a unique shape by which it was identified

silence: the absence of sound

solfege: a music education method to teach pitch and sight reading, assigning syllables to the notes of a scale; i.e., Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, Ti, Do would be assigned to represent and help hear the major scale pitches

sound: vibrations travelling through air, water, gas, or other media that are picked up by the human ear drum

tempo: relative rapidity or rate of movement, usually indicated by terms such as adagio, allegro, etc., or by reference to the metronome. Also, the number of beats per minute

texture: the way in which melody, harmony, and rhythm are combined in a piece; the density, thickness, or thinness or layers of a piece

timbre: the tone color of each sound; each voice has a unique tone color (vibrato, nasal, resonance, vibrant, ringing, strident, high, low, breathy, piercing, rounded warm, mellow, dark, bright, heavy, or light)