10.5: Incorporating Evidence

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 147053

Learning Objectives

After completing this section, students should be able to:

- explain how using support materials impacts speaker credibility.

- differentiate between internal and external evidence.

- distinguish the three types of testimony.

- distinguish the three types of examples.

- differentiate between descriptive and inferential statistics.

- cite a source appropriately.

- judge the validity of a source.

Once we have a clever idea of what we want to say in the speech, we need to find and include supporting materials. Supporting materials refer to any type of evidence, explanation, or illustration we use in the speech to enhance the likelihood the audience will accept and believe what we say.

Credibility

We use support materials because we need to enhance the credibility, the believability, of our message to the audience. Our audiences will only believe our messages if they can have faith that what we are saying is reflective of the truth or the best ideas. Audiences should believe in us as speakers and in our message. The use of supporting materials builds our credibility and the credibility of our message.

In today's political climate, the ability to identify quality evidence is extremely important. With claims of "fake news" being used to dismiss any information not meeting one's pre-existing beliefs, our ethical obligation to identify the best sources of information is greater than ever. Compounding this challenge is the plethora of websites established to advocate certain viewpoints, cherry-pick news stories for the most sensational tidbits, or outright fabricate news stories. More than ever, we must be critical consumers of information, carefully assessing what we are reading and hearing to separate truth from fiction, and reality from sensationalism. As speakers, we must use that same critical process to ensure we are presenting evidence to our audience that can withstand scrutiny. To that end, later in this section, we present the CRAAP Test for evaluating sources.

- When using evidence, especially from outside our own experiences, we rely on credibility transfer. We select good, quality sources we anticipate the audience will find credible, with the hope that by using that source, the credibility attributed to the source will transfer to us as speakers. That is why good, clear source citations are so important. By citing the source, we are giving information to the audience to allow them to establish the credibility of the source and enhance our credibility as the speaker.

- There are two broad categories of evidence: internal and external. Internal evidence refers to our own firsthand experiences, knowledge, and opinions. The evidence can be strong if the audience sees us as having expertise in the area. As the audience's perception of the speaker's credibility increases, the speaker can rely more on internal evidence and less on external. However, even highly credible speakers will still use external evidence as well to enhance their expertise.

- External evidence is the experiences, information, and opinion from someone other than the speaker. For external evidence to carry weight, the audience must view these external sources as credible.

Types of External Evidence

There are three types of evidence: testimony, examples, and statistics. Each one has its strengths and weaknesses.

Testimony

Testimony refers to quotations by others about the topic. When quoting someone, we can either quote verbatim, or we can paraphrase. When quoting verbatim, the speaker is quoting the person exactly as the person said it. This works well if the quotation is worded in a powerful, memorable, impactful manner. Paraphrasing is restating what the source said in the speaker's own words but keeping the meaning of what was said. Paraphrasing is especially valuable when dealing with longer quotations, or with quotations in which the wording is confusing or not as engaging as the speaker wants. Regardless of why the information is paraphrased, the speaker has an ethical obligation to make sure the quotation is translated in a manner keeping the intent of the original.

There are three types of testimony: lay, prestige, and expert.

- Lay testimony refers to statements by the "person on the street." These can be effective as audience members may relate more to "someone like me." Infomercials use lay testimony heavily to try to prove the advertised product will work for "someone just like you." It is important to remember a lay person is not an expert, so the proof value may not be as high as the speaker assumes.

- Prestige testimony is from someone who is well known but is not considered an expert in their field. Examples would include statements by celebrities like John Stewart, Stephen Colbert, or from the world of movies, television, or literature. They are usually used because of their interesting, engaging nature, although their ability to seriously prove a point is not strong. These are virtually always quoted verbatim.

- Expert testimony is from someone who is an expert on the topic. These quotations carry the most weight of the three types of testimony if the audience sees this person as being highly credible. Expert testimonies are usually found in newspapers, magazines, journals, or off internet research sites. Their weakness is often the wording can be dry and "academic" in tone, so frequently the speaker will need to paraphrase the quotation to have it carry more "punch" with the audience.

Examples

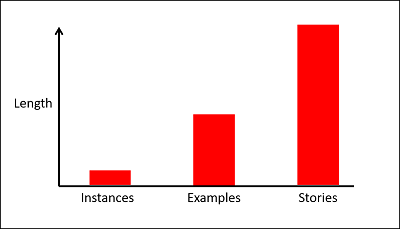

Examples are narratives relating to the topic. They can range from instances to examples to stories, depending on length.

- An instance is a quick reference, usually in a word or two, about a specific occurrence. For example, "D-Day" would remind the audience of a larger specific event, or "9/11" would remind the audience of the attacks on the World Trade Centers. Be sure the audience understands the reference. For example, for many people today, making a reference to "Columbine" may not be as effective as it was a few years ago.

- On the other end of the continuum are stories. Stories are fully developed narratives with a beginning, middle, and end. They can be used for longer speeches but are usually too involved for shorter speeches. The advantage of stories, if given well, is that they can be very involving and interesting. If they are not told well, they can end up being boring. The keys to using stories effectively are that the speaker tells the story well, and the story has a point that adds significantly to the purpose of the speech.

- In the middle is the more common example. When using an example, the speaker gives the pertinent details but does not develop it as a full-blown story. For example, to illustrate a speech on drinking and driving, a speaker might give some examples of individuals who were injured and the long-lasting effects. Saying only the name of the victim would not work, nor would the speaker want to tell the whole story of each person. The speaker gives the vital details of each example, enough so the audience understands the point of the example.

Examples are a highly effective form of proof with an audience, although by themselves they do not often prove the breadth of the problem; one or two examples do not prove there is a widespread problem. However, due to the human interest that we experience with examples, they have the ability, when well delivered, to involve the audience more on a human, emotional level than on a rational, cognitive level.

Statistics

Statistics refer to the numerical representation of data. Statistics can be the most powerful form of evidence to prove the extent of a problem; however, they can also be horrendously misused. In western culture, we tend to believe once a problem has been quantified and expressed in statistics, the statistics are inherently truthful. Statistics can be manipulated, misused, and misrepresented just as any other evidence can be misused. Speakers must be especially cautious when selecting statistics to be sure the numbers come from a quality source and are accurate reflections of reality. Statistics are used in two ways: descriptively and inferentially.

- Descriptive statistics describe what was true at a given moment in time. They describe data from the past. The past can be distant, such as in years, or recent, such as hours or days. The statistics reflect what was found when the statistics were gathered. For example, if a poll is taken on a Monday to determine which of two candidates is ahead in a political race, the statistics reflect what was found on the day. If on Wednesday, the media reports one candidate was arrested for drug dealing 10 years earlier, the results of Monday's poll become worthless as they reflected the results prior to the revelation of the drug dealing. When asked what the enrollment of Ridgewater College is, we usually refer to what is called "10th day enrollment." The enrollment of Ridgewater on the 10th day of the semester is used as the official attendance figure, but since students tend to drop out throughout the semester even on the 11th day the number may be wrong. Descriptive statistics report what was found on the day at the time. Descriptive statistics are the type we encounter most of the time.

- Inferential statistics are used to predict what may happen in the future. Simply taking descriptive statistics and assuming what they report will be true in the future is a faulty assumption. Rather, inferential statistics are specifically developed to predict behavior. For example, if a study establishes through valid research that as the poverty rate increases crime increases, we could infer if a community experiences a rise in the poverty rate, they are likely to experience a rise in the crime rate. The statistics link behaviors together. Physicians use statistics inferentially daily. As medications are tested, statistical relationships between variables, such as weight, and therapeutic effect are determined. Doctors then use the statistics to determine the appropriate dosage for a given patient, predicting with a high degree of confidence the medical outcome.

Whether used descriptively or inferentially, statistics have some distinct issues:

- The Source: Hundreds of organizations in the U.S. have the goal of persuading the American people and the American government to a specific position. Since their goal is inherently biased to one position, statistics released by the organizations are inherently biased. Even if the statistics they release were gathered and processed properly, they will be selective in which statistics they release, publishing only ones supporting their position.

- Gathering/Processing: Gathering and processing statistics have distinct guidelines. If statistics are not gathered using the guidelines, the quality of the statistics is highly questionable. Get statistics from reliable sources to produce quality statistical data.

- Interpretation: It is important speakers use statistics honestly, not inferring conclusions from them the statistics may not support. For example, if a speaker has statistics that 60% of Americans favor "handgun control," they should not use those to claim that most Americans favor "gun control;" the statistics are specific to handgun control, not gun control in general.

- Presentation: Statistics can be very confusing. The use of graphs helps immensely in clarifying numbers. It is up to the speaker to make sure the audience understands what the statistics are saying.

Evaluating Sources

Regardless of the type of evidence used, a core ethical speaker's responsibility is to present the audience with quality, trustworthy information. One way to do this is to apply the CRAAP Test to sources. Adapted from “Evaluating Information—Applying the CRAAP Test," from the Meriam Library of California State University, Chico, there are five criteria to apply when evaluating sources:

Currency: The timeliness of the information.

- When was the information published or posted?

- Has the information been revised or updated?

- Does the topic require current information, or will older sources work as well?

- Are the links functional?

Relevance: The importance of the information for the speech.

- Does the information relate to the specific purpose of the speech?

- Who is the intended audience for the information?

- Is the information at an appropriate level (i.e. not too elementary or advanced for the needs)?

- Is this the best of several sources reviewed?

- Will providing this information from this source increase the likelihood that the audience will accept the speech content as valid and credible?

Authority: The source of the information.

- Who is the author/publisher/source/sponsor?

- What are the author's credentials or organizational affiliations?

- Is the author qualified to write on the topic?

- Is there contact information, such as a publisher or email address?

- Does the URL reveal anything about the author or source? Examples: .com .edu .gov .org .net

- Will this source be viewed as credible by the audience?

Accuracy: The reliability, truthfulness, and correctness of the content.

- Where does the information come from?

- Is the information supported by evidence?

- Has the information been reviewed or refereed?

- Can the information be verified in another source or from personal knowledge?

- Does the language or tone seem unbiased and free of emotion?

- Are there spelling, grammar, or typographical errors?

- Can the accuracy of this source be easily defended?

Purpose: The reason the information exists.

- What is the purpose of the information? Is it to inform, teach, sell, entertain, or persuade?

- Do the authors/sponsors make their intentions or purpose clear?

- Is the information fact, opinion, or propaganda?

- Does the point of view appear objective and impartial?

- Are there political, ideological, cultural, religious, institutional, or personal biases?

Oral Citations

Whenever a speaker uses any external sources, an oral citation must be given. One major reason is to avoid plagiarism, presenting others’ ideas and words as one’s own. Citing sources also facilitates the credibility transfer process discussed earlier. If the speaker does not cite the sources, the audience will not know the sources were used; hence, the credibility transfer process will not occur.

In a speech, sources are cited differently than in writing. Obviously, we cannot use footnotes or give a list of works cited at the end of our speech. Instead, the speaker should orally cite the sources where they are used.

Speakers can be creative and vary how the source is cited and when it is cited. They should be cited smoothly, fitting into the overall flow of the speech. When citing the source, give enough information so that an audience member could locate the source in the future and the audience can also decide on its credibility.

Here are some examples of typical oral citations:

- “According to the May 3, 2009, Star Tribune article by Dr. Amy Fisher…”

- “Dr. Dana Brown, Director of the Breast Cancer Research Fund, said in last week’s Time magazine, that…”

- “John Gray, in his 1992 book, Men are From Mars, Women are From Venus, explained…”

- “Just last month in Esquire magazine, Stephen Colbert said…”

They are more casual and succinct than citations in a research paper would be. Some instructors require students to hand in a typed bibliography and will usually want it in either MLA or APA format. Students should pay attention to their instructor's expectations.

Key Concepts

The terms and concepts students should be familiar with from this section include:

Supporting Materials

Credibility

- Credibility transfer

Categories of evidence

- Internal

- External

Types of External Evidence

- Testimony

- Lay

- Prestige

- Expert

- Paraphrasing

- Quoting Verbatim

- Examples

- Instances

- Examples

- Stories

- Statistics

- Descriptive

- Inferential

- Evaluating Statistics

Evaluating Sources

- Currency

- Relevance

- Authority

- Accuracy

- Purpose

Source Citations

Reference

Meriam Library, California State University, Chico. (2010). Evaluating Information—Applying the CRAAP Test. Retrieved from www.csuchico.edu/lins/handou...l_websites.pdf