16.2.1: How to Be a College Student

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 90308

- Kris Barton & Barbara G. Tucker

- Florida State University & University of Georgia via GALILEO Open Learning Materials

Author: Barbara G. Tucker, Professor of Communication, Dalton State College

Many students who take a basic public speaking course are enrolled in their first semester or year of college. For that reason, in this fourth edition of Exploring Public Speaking, we include helpful material on making the life transition to being a college student and thus a lifelong learner. Your instructor may or may not assign you to read these appendices, but we hope you will consider reading them even if not assigned.

The Journey

In some ways, going to college is like taking a journey. It will feel like a different culture with a different language, customs, expectations, and even values. Consider these appendices as a guidebook for the journey.

In choosing the metaphor of a journey for college, we are comparing them on several factors.In choosing the metaphor of a journey for college, we are comparing them on several factors.

- Like a journey, rather than a weekend trip, college is a long process. The journey takes time.

- A journey goes through different terrain. Sometimes you will feel like it’s more uphill than downhill.

- A journey involves guides, people who have been there before and have wisdom about the way to get to the destination. These are your professors mostly, but also your academic advisors, peer mentors, administrators, older students, and staff in Enrollment Services and the Dean of Students’ Office.

- A journey requires a map. This is, for the most part, the college catalog that tells you what courses are required to fulfill your major. Your advisor can also probably provide you with a “course plan,” which breaks down in order which classes you should try to take each semester.

- A journey has a destination. Here is where you might find that your values are different from your professors or mentors. Many college students see this destination as commencement day and getting a diploma in front of family and friends. That is only part of it. Your professors and mentors want you to be introduced to ideas, books, authors, and experiences that you will continue to engage with throughout life.

Your destination for now is probably the career you see yourself working in five years or more from now. You probably chose a major or perhaps even the college based on that career destination. That is reasonable and you were probably encouraged by your high school teachers, counselors, spiritual advisors, and parents to do that.

Why College?

However…there are a few problems with approaching college with only a career destination focus.

First, you are likely to change your mind. Most college students do at some point. In fact, according to Gordon, Haubley, et al (2000), 50% – 70% of students change their majors at least once, and most will change majors at least 3 times before they graduate.

Second, you may have to change your mind about your major. Some college majors are competitive, meaning a fraction of those who want to get into them are accepted, based on grades and other factors.

Third, you might want to change majors as you are exposed to new ideas and career fields you didn’t even know about.

Fourth, the career you end up in may not even have been invented yet. In 2007, when the author’s son started college as a communication major, no one had heard of a social media director. That is what he does now. Conversely, some of the hottest jobs now might not be so hot in five years. Technology is changing, knowledge is expanding, politics alter realities, and the population is getting generally older. These trends will affect the kinds of jobs that are created (Anders, 2017).

Fifth, and more to my point, college is about becoming a better version of you, not just getting a job. If you see the main point of college as coming out with a career, you will miss some of the best parts of the journey. Or even worse, if you feel that every class is just an obstacle to that career rather than a stepping stone to being a more prepared individual for that career, you will miss the value of each class. And let’s face it; you are going to take at least forty classes over the next four to six years. You want to enjoy them, not just see most of them as roadblocks to getting out.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I am not saying you should spend all this time, effort, and money to get a piece of paper that doesn’t take you to a career path. But note, I say career path. It is highly unlikely you will not walk off the platform after graduation and into the perfect job you will stay in for decades. The reality of today’s workplace is that you will have many positions and perhaps many careers over your forty or fifty years of work life, and college cannot prepare you specifically for all of them right now.

What college prepares you for is to be a lifelong learner who can adapt yourself and your skills to the new jobs the marketplace will create or will interest you in the future, and the new skills you will be expected to have in your chosen career field. If you want to be a registered nurse and graduate with a bachelor of science in nursing, that will just be the beginning of your learning to be a competent, caring nurse.

You have probably heard it before, but the top skills employers want, inappropriately called “soft skills,” have more to do with personal abilities. Team work, critical thinking, work ethic, spoken and written communication, conflict resolution, and group facilitation are common skills seen on lists of what employers want in new hires. (Go ahead and do an Internet search for this subject, and you will see what I mean). The soft skills, which are really not soft but the basis of your success, are what you learn in college classes and college experiences outside of the classroom. (The term “soft” does not refer to them being squishy but fluid and transferable to different contexts. Professors in the liberal arts really do not like the term “soft skils” by they way, because they sound “less than” something important.)

In other words, college is not a vocational program that trains you for a specific job. If that goal interests you, you should consider it, because the workplace desperately needs skilled workers such as electricians, plumbers, technicians, and the like. College is designed to help you attain (not give you) a wide set of skills and knowledge so you can adapt, grow, communicate, and learn no matter what field you pursue, as well as give you more specific skills for certain positions.

Also, college will not be the end of your learning. You may want to attain another credential or degree after graduating from college. You will definitely be expected by your employers to be involved in for-credit and not-for-credit continuing education. This is the just the beginning of the learning journey. Yes, you have been learning since birth and in school since you were four or five, but there is one difference now: you are learning because you want to. Learning is now your choice.

So, every part of the college experience, even the hard parts, should be seen as part of the journey. If you’re hiking in the mountains, the view from the top will be magnificent but you might sweat a lot, trip and get scrapes, or tramp through some thorny bushes before you reach the summit.

However, if you prepare for the journey and stay on the right path, many of the problems can be avoided. That is the purpose of these appendices.

Preparation

Of course, much of your preparation for college came in your K-12 years. You learned to read and write, solve equations, perhaps speak the basics of a foreign language, and perform many other academic tasks. You also probably learned about working with others, solving problems, and taking responsibility through musical groups, sports teams, clubs, and other extracurricular activities. In some ways, college will be a continuation of those years, but many students find that high school did not prepare them for everything that college brings. There are many reasons for this lack of preparation. The question is, “If you find yourself unprepared, what can you do about it?” That is the subject of these appendices: Getting the big picture of what college is about; understanding your friend, the instructor; time management; appreciating how we learn and you learn individually; studying, reading, and test-taking; and avoiding the plagiarism trap. We will finish up with some resources on campus.

Part 1 of Appendix B will deal with the first two; the others will address the remaining five.

Getting the Big Picture of College

The institution of the university has actually been around longer than high schools or elementary schools. The first university was founded in Morocco in 859 C.E., the University of Karueein. (A college is traditionally considered a section of a university as well as an independent unit; today “universities” usually refer to institutions with graduate programs.) Oxford University in England came along in 1096. For that reason, centuries of tradition still cling to the culture of colleges and universities. Traditions change slowly, especially when they have been around over 1000 years! Part of being a college student is to learn the physical and cultural terrain of the college, much of which comes from traditions.

Colleges and universities are generally separated into public and private. In most cases, public institutions are in a system of related colleges or univesities in a state. The author’s college, Dalton State, for example, is a unit of the University System of Georgia, which means a number of positive things for students. They have access to books in all the libraries in the University System of Georgia, as well as other resources. Their credits can transfer easily to other institutions in the University System of Georgia, although we prefer for students to stay here and not transfer! To a large extent, the curriculum (the nature and number of courses taken) is determined by the University System of Georgia.

A college degree is either a two-year (associate of arts or science) or fouryear (bachelor of arts, bachelor of science, bachelor of fine arts, bachelor of social work, bachelor of business administration, etc.). Associate’s degrees are usually limited to 60 required hours . A bachelor’s degree is usually limited to 120 hours. There are, of course, some exceptions to these standards. Most colleges have a set of “have to” classes for eery student; these might include a “core” of general education courses (some required, some elective)); and then required and elective courses for the student’s specific chosen major. Some programs are very closely proscribed (few elective choices, usually health professions and education), and some give the student more flexibility.

For example, at Dalton State, there are 42 hours of required “core” classes. Although you have some options to choose from here, you still have to take a certain set of classes. These 42 hours are divided into five areas called A-E:

A: Essential Areas (English 1101, 1102, and a math course) B: Institutional Options (for Dalton State, you take COMM 1110 and a one-hour academic elective) C: Literature and Fine Arts D: Science and Math, including two lab sciences E: Social Sciences (including required American Government and U.S. History)

Then there is Area F, 18 hours, which will be different depending on your major. In some majors you have choices in Area F; in some, for example, everything is set by state or accreditation standards. Other coleges, public and private, typically have similar breakdowns or requirements for “core” classes. Then in the junior and senior year, the student takes 60 or more hours of courses in the major and perhaps a minor.

Many students feel that some of their freshman year classes are repeats of what they had in high school. Unless you took AP or dual enrollment classes, your freshman year classes will be much more demanding than those high school classes, even if some of the material is review.

All that said, the curriculum of college is not something a bunch of people in a room thought up last week. It is the result of those hundreds of years of what has traditionally been considered important to a college education. History—how did we get to where we are? Social sciences—how do we relate to other people? Literature, language, and public speaking—what are the best ideas and how do we communicate them? Sciences—how does the physical world work? Math—what is the logic behind numbers? You can argue about the value of any one of them, but years of tradition have solidified that these are what an educated person needs to know about. The configurations of classes may differ from college to college, but the basic concepts are the same.

Advising and Your Classes

The subject of the curriculum brings us to another matter that students often do not understand about college. Each college or university system is “autonomous.” Each has its own curriculum and set of required classes for a particular major or degree. Each college has the right to accept or not accept courses for transfer from another institution. This may seem unfair, but that is part of the tradition of higher education and not likely to change anytime soon. If you transfer from a public to a private institution, or vice versa, or to a college out of state, some of your credits may not be accepted for transfer there.

Also, our academic advisors cannot advise you for another institution, only for this one. If you plan on transferring, you are responsible to talk to the other institution about requirements and what will transfer. Since you don’t want to take a class that will not count toward your final degree and you don’t want to lose time, credits, and money, be in contact with the school you hope to attend later.

Speaking of advisors, they are your best resource for making educational choices. At the same time, they want you to develop the ability to make your own academic decisions, specifically by being able to read the catalog, the course plan, Banner and Degreeworks (these last two are common student record and degree auditing systems; your college may have a different “brand” of this software). You can then see what classes you need each semester and design your schedule. They are willing to help you in the freshmen year or if you change your major, but after a while the advisor (who might be a faculty member) will want you to take ownership of this process, with their help and approval. Some things to keep in mind about advising:

- As freshmen, almost all the courses you are required to take in the core are offered frequently, usually every semester and with many sections, so you will not have trouble finding those courses when you need them.

- As you become a junior and senior, the courses may only be offered once a year, at a time that is not convenient, and/or even every two years. You will have to plan accordingly.

- Learn to use the records system and degree auditing software; they are great tools. If you advisor doesn’t mention it, ask about it.

Another very important point about advising: Financial aid questions must be addressed to the financial aid office staff in Enrollment Services. The professional and faculty advisors usually have no access to your financial aid information. Students often run into financial aid problems for a number of reasons: dropping too many courses, failing to pass enough courses, and taking courses that are not required in their program are three major ones. Not completing the FAFSA on time is also a huge obstacle to navigating the financial aid universe. The financial aid office staff are the experts and you need to check your email, Banner, and your postal mail for notices from them about deadlines and your awards from financial aid.

Additionally, the college most likelyexpects payment before the semester begins. In fact, if you do not pay your bill or make sure your financial aid is in order a couple of weeks before the start of the semester, your registration will be “purged” or removed—you will no longer have a class schedule, even if you had registered very early. Dates are advertised on the website and calendar. Obviously, you do not want this to happen, because you have to begin all over again trying to get into classes, and by then they might be closed to new registrations. This is why you should have a way or plan to take care of the fees and tuition as soon as you register.

So, to recap, college is a new terrain, and the college experience is a journey over that terrain. The terrain has a physical and cultural features. The physical one is the actual campus, which for Dalton State involves many buildings over more than 40 acres of land. The cultural one involves the rules and regulations, the language, the values, and the persons and personalities. In the next section we will talk about the people most affecting you—the faculty—but first I’d like to address the values of higher education.

Values

The first value is rigor. That means the learning tasks require effort from students. You could say it means the courses are hard, but there is more to it than that. It means the academic standards and expectations are high. At Dalton State, we have a tradition of being a rigorous college. Our students who transfer do very well historically at other colleges. Our health professions students do very well on certification exams. To be honest, we take pride in being rigorous and having high standards but also in empowering the students to meet those standards through good teaching. Teaching is what our faculty do, and it is our priority.

The second is diversity and inclusion. College will allow you, and sometimes force you, to encounter people and ideas that you have not before. Your instructors may be from other countries or parts of the U.S., as might be your classmates. You will have classmates who are twenty or even thirty years older than you—or younger. Your instructors may teach theories and concepts you personally disagree with. One thing that students often find in college is that the old cliques and “drama” that happened in high school simply don’t apply in college. It’s about the learning and the work, not social status, cliques, or in-groups. Everyone belongs, no matter what they look like, as long as they do the work.

The third is civility, which can be thought of as “actively showing respect.” Not agreement, but respect for them as human beings and members of the community and as persons who have a right to express their opinions with civility as well.

The fourth value is equality and fairness. You might not always think it is true in your experience, but higher education values access (availability of learning to those willing to work hard), equality (not getting a grade for any reason other than performance, and not giving or asking for special treatment) and fairness (equal output for equal input). For that reason, if you ask a professor for special favors, you are asking him or her to be unfair to the rest of the class who did not get those favors.

Now, in case my emphasis on work is making you worry that there is nothing fun going on at your college, let me stop here and say that it offers a wide variety of programs for social interaction, relaxation, fun, and developing relationships, spirituality, and leadership. The Dean of Students’ Office, the Health and Wellness programs, and the Athletic Department are three website you should check out right now just to convince you college is not all hard work and there is plenty of activities to get involved in here!

College Faculty

I have mentioned faculty several times in this section on values, and there is a reason for that. The persons you will have the most contact with on campus, other than students, are your faculty. You may spend several hours a week with them. It is best if you start to think of them in positive and constructive manners rather than as stern, rigid, distant authority figures who have no connection to your lives. The following is from a PowerPoint I created for a first-year seminar course taught in 2016 I called “The Care and Feeding of College Faculty.”

Forget all the things you have heard about college professors. You might have been taught that college faculty:

- Spend most of their times writing books

- Are introverted, weird, or eccentric (the absent-minded professor stereotype)

- Have inappropriate relationships with their students (while this has happened in some colleges, it usually ends badly, as in unemployment. )

- Don’t work very hard (We might only be on campus about 30 hours per week, but we work away from the office many more hours.)

- Are mean. Students have informed me that their high school teachers told them that college professors were uncaring. Perhaps they said that so that the students would not expect the professors to be easy; perhaps those high school teachers did have bad experiences. I can say this is not the case at Dalton State and probably not at your institution.

You will find your instructors to be warm, polite, helpful, and friendly—but professional. Part of growing up is to learn to negotiate between those two.

These mistaken and questionable ideas often come from TV and movies are questionable. However, college faculty do have specific characteristics.

- They LOVE their discipline. They live their discipline. They went to school for years to understand their discipline. They think it’s the greatest thing ever. I teach communication and do not understand why the subject does not fascinate everyone. Consequently, don’t blow off their subject. Don’t say it’s worthless or boring or of no value. How would you feel if someone did that to you?

- They like to question, so they seem skeptical. In pursuing graduate degrees necessary to be a college teacher, we are taught to question ideas and assumptions. Sometimes we say things in class for you to think about, even if we don’t agree with it. We expect you to follow the syllabus and do the assignments. The syllabus in college means much more than the syllabus in high school; you should keep it in a prominent or accessible position in your notebook.

- They have different personalities. Some of us are extraverts and some are introverts. Some have quirky senses of humor and some have fairly quiet ones.

- They are in total charge of their classrooms. College instructors are not to be disturbed when teaching. Do not walk into a college instructor’s class and interrupt in the middle of a session, unless the building is on fire or it’s a matter of life or death.

- Higher education changes slowly, and so do faculty. Colleges were originally run entirely by the faculty; there was not really a separate administrative staff. Even today, many college academic policies cannot be changed without the approval of the faculty. For example, we cannot change federal financial aid policy, but we can change the curriculum in a major if we choose to do so.

- Professors at Dalton State are student-oriented. We chose to work here because it is a teaching institution, which means our main responsibility is to teach, advise, and serve students, as opposed to doing research. We do engage in research, but that is not our priority.

- They don’t treat some students better because they like them.

- We have heavy workloads. We teach 3-5 classes per semester, with varying numbers of students—as few as ten, as many as 100 or more. We have to keep office hours, one or two a day, which does not include committee meetings (faculty participate in governance of the college, and that takes time), advising students, preparing classes, grading, assessments, and required continuing education.

- We have families and lives, too.

- College faculty do not deal with parents. It is against federal law for a college instructor to talk to your parents about your status (that means grades) in their class. That law is called the Buckley Amendment and often referred to as FERPA because of its origin in the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act. If a parent calls and asks about a student–and it does happen occasionally–we just say we are not allowed to talk about a student’s progress to parents or anyone else outside the College personnel. There is a way around this law; the student can sign a waiver of his or her privacy rights in Enrollment Services. But our first response will be to refer to FERPA.

- As adults, authority figures, and experts in their subject matters, faculty members expect respect. It is best to refer to him or her as “Professor” if you do not know if the instructor has earned a doctorate, and as “Dr.” if you know they have (it will probably be on the syllabus). We work hard for the doctorate and it is professional courtesy to use it. Some will say it is all right to call them by their first name (very rare) or “Mr.” or “Ms.” but unless they do, you should default to “Professor.” You should also learn your professor’s name and office location on Day One. The instructors keep office hours mainly for students to come see them about class matters. You will not be bothering them.

- Keeping all these characteristics in mind, here is a list of Don’ts that will keep you in good shape with your professors. Don’t…

- Ever ask them if anything important happened in class on a day you were absent. This is literally the Kiss of Death and you may get a very harsh or sarcastic answer, such as “No, since you were not there, we put our heads down and thought about your absence.”

- Don’t email them like text speak. Emails should start professionally, “Dear Professor,” identify who you are and your class (the email address may not do that), and clearly give your question or concern. You should have a closing as well. Your relationship with your faculty member is a professional one and this is a good time to learn professional communication. Many professors simply will not answer an email like this:

hey I missed class today can I get the notes from you or the power point? Bill

Yes, I have gotten emails like this from students

- Expect special treatment. Fairness to students is extremely important to us.

- Play with your electronic devices in class. I cannot stress this one enough. Each faculty member will have a policy on phones and laptops, and you must abide by it. Remember, we are in control of our classrooms. Faculty are also allowed to call public safety and have students escorted out of class if they are really disruptive or causing harm to other students and their learning.

- Think attendance doesn’t matter. This is one of the biggest lies that is propagated about college life. Attendance in class does matter, very, very much. No, we won’t call the county truant officer. However, many faculty take daily roll, and we have to keep some record of attendance for financial aid purposes. So, we are aware of your attendance, but more important, you will not do well by missing many classes, even in a class that is purely lecture and test-taking. Lots of research shows this.

- Be afraid to go to their offices and ask for help. It’s one of the best things you can do if you are having academic concerns. If you do go to their office, however, don’t overlook the office hours sign on the door (also on the syllabus). If the professor has informed the students that she is in from 1:00-3:00 on Thursday afternoon, don’t expect her to be there at 4:30.

- Think your instructors are psychic. If you never ask questions in class, even if you have them, we are not mind readers. Please ask.

At the end of the semester you will be asked to evaluate your instructors online. First, please comply. The data is important to the college’s operations. Second, answer thoughtfully. Third, don’t blindside the instructor. If you say “He never explained X clearly,” did you ask about X? Fourth, don’t get ugly and personal; swearing or obscenity on the evaluations isn’t helping anyone. State your case about the instructor’s behavior, not that you didn’t like her shoes. The evaluations are about the learning experience in the class, not whether you think the class should be in the curriculum.

Parting thoughts

While there are a lot more things I could say about the journey of being a college student, some things you just have to experience. Not everything will make sense at first. Remember, it’s a long journey.

Expect your college life to have a cyclical nature. The first few weeks will be exciting and daunting; you may feel like your head will explode with all the newness. A few weeks in you might feel a little down. The newness has worn off and man, oh, man, the work is piling up. By the eighth week, it will feel like everything came at once, but you do get a short break about then. The stress and activity builds and builds until finals and whew, it’s time to sleep and binge watch shows on Netflix. You say, “I got to get a better start next time” before it starts again in January.

I’m telling you this now because the key word I want to leave you with is PROACTIVITY. Your college journey will be enjoyable and successful to the extent that you are proactive. I learned this all-important word from the best book on time management, The Seven Habits of Highly Successful People by Stephen A. Covey. In a sense it means “planning” but more than that. Because we cannot plan for everything, we plan margin and solutions for what we know we cannot plan for. I cannot plan when I will have a flat tire; I can plan to have the resources in my car to fix the flat when that happens. I cannot plan the traffic between my home and the campus, but I can plan to leave 10 minutes early every day to get a parking space and miss the worst of the traffic.

Proactivity is about having a future-orientation that is executed in the present. Paper planners, or electronic ones, can help. But you can write down or type into your phone all the plans you want if you don’t choose to execute the plans. After a while, proactivity can become a habit and you cease to even recognize it as such. For example, years ago I learned to put my clothes out the night before a workday. My husband sets the coffee pot up before going to bed. These are small things but they save loads of time and more importantly, stress. Much of the stress we feel is self-inflicted from poor planning.

It is common for textbooks on transitions for first-year students in college to contain a chapter on time management. In place of a separate chapter or appendix, we will include some online resources. Inventories, filling out sample weekly calendar/schedules, and tips on time management are very helpful, but they start with this attitude of proactivity and some of the mental processes discussed in the Part 2, specifically self-efficacy and locus of control. Now is the time in your life to realize that there are urgent things and important things in your life, and those will change as you go through various seasons.

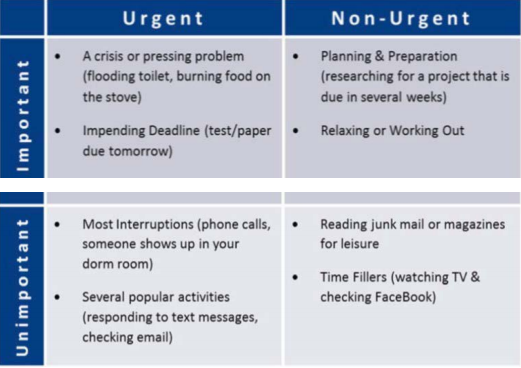

Urgent means that for whatever reason the task must be done very, very soon. Important means that it is central to your values and to your reaching your goals. Urgent means the task or activity demands your attention now; important tends to mean it will demand your attention long-term. Some things are simply urgent, but not important; some are important but not urgent; some are neither, and some are both. The diagram on the next page is often used to show that comparison.

Many of you have family and work responsibilities. Being a student is one of your many roles. This means balancing priorities; you have more things in your life that are both urgent and important. For that reason, using tools such as planners are a must for you. As a friend of mine says, everything takes longer than it takes,” so be realistic about trying to pack too many activities into your day. For your health and good relationships, you need to plan “margin” in your life, time in the day that is not packed to the full. That time will probably be taken up by the urgent and semi-urgent things that come up that you can’t plan for or expect.

Here are some resources that can help you with time management:

https://www.mindtools.com/pages/main/newMN_HTE.htm

http://www.rasmussen.edu/student-lif...-tips-college/

https://www.usnews.com/education/blogs/professors-guide/2009/10/14/top-12-time-management-tips

https://www.projectsmart.co.uk/smart-goals.php

In conclusion, time management is more about self-management than the clock. You can’t really manage time—it keeps going forward, no matter what we do. You can only manage your own goals and behaviors, and college life will bring the importance of that home to you.