16.2.2: Learning to Learn

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 90309

- Kris Barton & Barbara G. Tucker

- Florida State University & University of Georgia via GALILEO Open Learning Materials

Author: Barbara G. Tucker, Professor of Communication, Dalton State College

“Remember, in business and in life – success is earned from learning how to do things that you don’t like doing.” (Llopis, 2012)

One of the most important things that you will learn in college is how to learn. Why does that matter? Because learning will be one of our jobs in the future. No matter what profession you eventually enter after your formal education—social work, nursing, accounting, social media director, elementary school teacher, business manager, respiratory therapist, banker, or one of many others—you will continue learning new procedures, new policies, new techniques, new ways of thinking. Your employers will expect you to attend training. You may decide to change careers completely or slightly and have to learn new skills. Software and technology change constantly. Many of you will eventually want to earn a graduate degree.

Psychologist Herbert Gerjuoy said many years ago, “Tomorrow’s illiterate will not be the man who can’t read; he will be the man who has not learned how to learn.“ “ This quotation has often been attributed to the futurist Alvin Toffler, who used it in his book Future Shock from the 1970s. These men’s words were prophetic, although they could not have foreseen all of today’s technology.

Of course, not every learning task will be the same as the type you do in college. However, the truth remains that you are only beginning to learn as an adult, and this is the time in our life where you can focus on learning, on understanding the process, on how you best learn, and how you can expand your repertoire to learn better.

There are many theories about how we learn. While in some cases they contradict, for the most part they complement and supplement each other because they concern themselves with different aspects of the learning process, either the physiological effects of learning on the brain and body, the social aspects, or the personal and psychological effects.

Thanks to magnetic resonance imaging (MRIs), other medical science, and the growing field of neuroscience, we know much more today about how we learn. We know that learning creates a physical change in the brain as synapses grow. We know that this happens not by passive reception or exposure to information but by our effort. We know that memories are formed by passing from a short-term category to long-term through rehearsal, usage, and other efforts.

We understand how attention works and that distractions inhibit learning rather than helping it. While you think listening to music may help you study, it probably is not, and your open laptop in class is distracting the students behind you. In fact, the idea of multitasking is a myth. You may think you can do several things at a time, but you are actually cutting the efficiency and quality of the work you are doing. In other words, you might get some things done when you multitask, but you won’t do them as quickly or as completely or as well.

We understand now that intelligence is malleable (change-able, flexible) and that a person with a fixed mindset about learning (those who say they are just born to be good at a skill like math, music, or writing) will face frustrations and obstacles in comparison with those who have a growth mindset. A growth mindset sees one’s failures in a learning task as ways to find new methods for learning, not as a stopping off point in learning. Also, to the advantage of all college students who sometimes feel like their heads are going to explode, we know that learning is not a zero sum game. Learning one thing does not mean it has to displace something else. Your brain is an organ that is developing new and more intricate connections; it is not a box that will only hold so much. We also know there are different kinds of knowledge and different kinds of intelligence, and we know there is a distinct difference in learning and processing between novices and experts.

We also know that some of the common ideas about learning do not have much evidence. One of them is learning styles. You have probably taken a test that classified you as a visual, auditory, or kinesthetic learner. While there is nothing wrong with being classified in such a way, there is no evidence from scientific studies that you will learn better if your instructor teaches to your learning style. Unfortunately, I have heard many students over the years attribute their failure in a class to the professor who didn’t teach to their learning style. What the students did not understand is that we learn through all styles (visual, print, hearing, and activity) depending on the demands of the learning tasks.

You did not learn to drive a car simply by reading about it or looking at videos (print, visual). You had to drive around in a car and listen to the instructor (kinesthetic and auditory learning). Think about learning how to ride a bicycle—same scenario. On the other hand, learning to speak a foreign language requires auditory and visual input, not just one, and is enhanced by movement. It would be better for you to use all four modalities than to pigeonhole yourself and limi

Like other labels, learning style labels may contain a grain of truth. A student who prefers to learn auditorily may find studying more productive when her notes are spoken aloud into a recording device and revisited later. But she may also find that when studying for a geometry test, drawing diagrams (visual) and physically manipulating shapes on paper (kinesthetic) work best for her.

In fact, it’s just as important what you do with the information after it is accessed (enters your mind) than how it gets in there! As a college student and developing adult learner, you will want to be aware of what learning tasks require, especially what they require of you in terms of effort, attention, and time. You will want to notice what you are doing when you learn and even when you do not learn as you hoped to. You will want to think about and talk about how you learn best because using language is part of the effort behind creating those synaptic connections. These behaviors are called metacognition, or “thinking about thinking.”

This need for metacognition is why your professors will often ask you to turn to your partner and discuss some of the lecture material, such as what was unclear– “the muddiest point”—or to compare notes you have taken. It is why your instructor might have you look at the questions you got wrong on that midterm exam and figure out why you got them wrong— what processes did you go through to get that answer, and where, perhaps, did you get off track. It is why your professor might give you a pre-test at the beginning of the course to see what your pre-conceptions about the material are.

Of course, learning is not just about adding knowledge but also reshaping your understanding and approaches. For an example, I’ll use public speaking. Students come into the class with ideas about public speaking that they have to “unlearn.” One is that they cannot do it, because of bad past experiences or fear. Another is that all they have to do to be a good speaker is be funny, even silly. Another might be that public speaking is not an important skill, or that public speaking is just reading to an audience. As another example, science instructors often see that their beginning students have faulty ideas about science as a field of knowledge as well as about specific scientific facts. Their goal is not just to fill the students’ minds with scientific facts but to think like scientists, to understand what the scientific process involves and to apply that process in new ways.

All this is to say that one of the things you will hear over and over again, and one of the things that is a major difference between high school and college, is “time on task.” College learning, because it is “higher” in terms of the thought processes your professors want you to engage in, takes time. You cannot jot off a ten-page paper in a couple of hours. You cannot study for a midterm for an hour the night before. Well, you can try, but how successful you will be, in terms of really learning and earning good grades, is up for grabs.

Six theories of learning I would like to present here that will be of value to you as a student are Bloom’s/Krathwohl’s/Anderson’s taxonomy, Albert Bandura’s self-efficacy, self-directed and self-regulated learning, the usefulness of mindset, Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development, and Kolb’s experiential learning cycle. What matters with each is that learning is effort. While learning can be enjoyable, the old “learning is fun” adage gives the idea that it is easy and that it shouldn’t require much effort. It learning does take effort, the erroneous thinking goes, then something must be wrong. On the contrary, learning is hard work.

Recently I signed up for an online course with an organization that credentials online courses. The organization’s purpose is to help instructors create excellent courses and to train college personnel in applying excellent standards to the course. I have taught online for almost twenty years but wanted to learn this organization’s system. It proved to be more challenging than I planned.

Because I had many years of experience in teaching online and reading about how to do it and design classes, I found I had to put aside some of my attitudes and ideas because of the philosophy and approach of this organization’s system. I had to “unlearn” some of my former ways of thinking about online teaching and course design. To “unlearn” doesn’t mean to forget, since memory is not something we can just erase like deleting a file from a computer. Due to my willingness to do that, I walked away with a deeper understanding of good online course design. I was also able (and this is another aspect of college learning) to transfer or apply that knowledge to my traditional classroom teaching.

What is one of the things I “unlearned?” I like to put lots of extra resources in my online class, as in “when you get a chance, this is something interesting to read.” I “unlearned” that that was a good idea. It just confuses the students, and unless it directly meets a learning objective or outcome, it does not belong with all the other materials. What I might do in a regular classroom doesn’t translate to online, not in all cases. That was a hard lesson for me because of my personality—I like to give students lots of choices! But it was a good one to learn.

In that personal learning situation I see each one of the six theories mentioned above. I see that I had to go up the taxonomy, and I had to be stretched into a new zone. I had to believe that my failure on the first assignments (yes, I failed them!) was not because I couldn’t learn but that I had to—and could—find new strategies. I also had to regulate my time and work on the class when I was mentally prepared, and I had to reflect on my experience to learn. Let’s talk about each one in more detail.

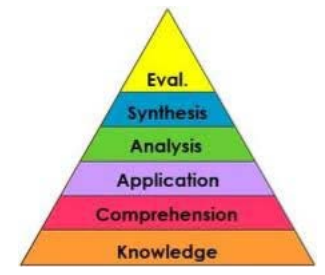

Bloom’s taxonomy was created in the 1960s to help teachers recognize that all learning was not the same and happened in an upward movement. This is a typical reproduction (source: Wikimedia.commons) of the original “taxonomy,” which means “a scheme of classifications.” In this case, it is classifying learning tasks.

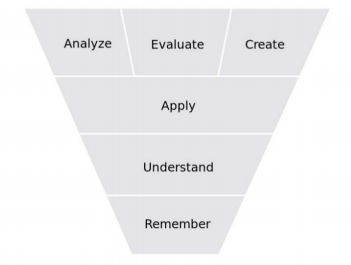

Later, in 2001, the model was updated to use verbs rather than nouns and emphasize the activity of learning. (Also from Wikimedia.commons) This configuration turns the triangle (or rhombus) upside down but other versions keep it like the one above

The important thing for you to get from this is that your instructors will have some learning tasks at the bottom—remembering facts or concepts, such as being able to recreate lists of information on a test, and understanding, such as being able to define the concepts in your own words . However, in higher education we move higher up the taxonomy. You will be asked to apply the learning, and then do new things with it. You will also be asked to learn a greater volume of information for tests, in most cases, than what you have been used to in high school.

So in a history class, obviously you will have to remember dates. Then you will have to be able to explain or define an historical concept such as Manifest Destiny. Then you will be asked to apply, such as “Did the concept of Manifest Destiny influence a president’s behavior?” In this case the instructor may have never addressed that question specifically in class; you are supposed to take the concept and compare it to what the president did and said. Those are the lower levels, and it is possible that those will be your major learning tasks in your first year or so of classes, although not entirely.

However, as you progress, you will be asked to:

- Analyze (taking apart, contrasting and comparing parts): “What are the beliefs behind Manifest Destiny and where did they come from?”

- Evaluate: Assess how a concept or practice stands up to other criteria, standards, or philosophies: “Does Manifest Destiny violate the U.S. Constitution in spirit or in letter?”

- Create: Develop a new thesis from the materials you have learned.

This is not to say you will be asked to do all six levels of the taxonomy in anyone class; in fact, that is unlikely. But I introduce this for you to understand what your instructors are trying to do. If you come into class with the pre-conception that you will be learning lots of facts and taking tests on them, that is only partly true. You will be expected to operate more at the applying, analyzing, and evaluating levels.

The second theory we will examine is that of Mindset. This theory is based on the work of Carol Dweck, a psychologist from Stanford University in California, and it has encouraged a great deal of research on learning. It is simple, “elegant” as some say, but also has a number of parts and offshoots.

Learning is work, sometimes hard work. You do not learn a task primarily because you are inherently good at that task; you learn it because you work hard in the right way. Learning researcher Angela Duckworth shows that experts—the really skilled—spend an average of 10,000 hours becoming that skilled person. For example, concert musicians and professional athletes do not approach their tasks as “I am just talented at this” and let it slide. They constantly practice and keep working on skills.

A person with a growth mindset sees learning as possible and due to hard work. They will try new methods to learn because they don’t see having the skill as either “born with it or not.” Also, a person can change their mindset; it would be against the theory to say someone could not change! Thankfully those who are trained to recognize how their fixed mindsets are affecting them can change to a growth mindset. Finally, children (and adults) should probably not be praised for being “smart” or “gifted” but instead for “working hard,” “finding new ways to do things, “ and having perseverance or endurance. (From https://mindsetonline.com/whatisit/ about/)

Closely tied to the idea of mindset is self-efficacy, which is “one’s belief in one’s ability to succeed in specific situations or accomplish a task” (Bandura, 1977). Self-efficacy is not just self-confidence, but is related to beliefs regarding specific tasks. Self-efficacy is tied to success in many endeavors, and to resilience and locus of control, which are also a large part of mindset. A person who believes that ability and talent are just natural and all that matters in success—absent from hard work and using the right techniques, practice, etc.—lacks self-efficacy. The mindset approach can help college students because they will be faced with daily events that can attack their self-worth and lead to dropping out, when what they often need is to find other ways to approach learning.

For example, let’s say that on your first Biology 1107 test you earn a 56. You say, “This is not me! I don’t get 56s on exams! What is going on?” You now have a choice. You can study exactly the same way for the next exam, maybe just using more of it or spending longer hours at it. That might work, and it might not. You can blame the instructor’s teaching methods. That is not going to help, because then your only option is to drop the class, something you do not want to do because it will become a pattern. You can say, “I told you so; I stink at science, so I need to drop the class and change my major so I don’t have to take biology.” Again, not a pattern you want to establish. You can do nothing and hope for the best (not a good option either).

Or you can:

- Examine your behavior in the class up to now. This is part of a process called reflection. Have you attended all your classes (that old myth that you don’t need to go to class in college rears its head again!) Have you read the material in the textbook outside of class? Did you come to class alert, having slept and eaten well? Did you look at your notes after class or go over them everyday, accumulating knowledge, or did you just wait until the night before the exam? All of these are standard things that college students are told to do, and it’s not because college professors want to control your life. THEY WORK.

- Go talk to the professor during posted office hours (and don’t expect them to be there at other times) to ask for help and some ideas for succeeding in the class.

- Attend the tutoring services offered by the Dean of Students’ Office.

- If your instructor offers outside of class sessions, take advantage of them.

The process of reflection is vital to college learning. You start by reflecting on what led up to the experience, as well as how you felt about the low grade and even the experience of taking the exam. What was on the test that you didn’t expect? Did you study word-for-word definitions but the test asked you for applications? Did you memorize lists but it asked you to put concept in your own words? Was there a whole section of the textbook that you just skipped?

After reflecting, you have to make a plan for the next time and take action. It may be that your problem was not the amount of time you spent, but when you spent it and what you did during the time. For the purpose of learning and memory formation, repetition (going over the accumulated class notes every day or several days a week) would be better than what we call “cramming.” Spending ten minutes a day for 21 days (three and half hours) will be more useful than cramming for five hours the night before, which is time you might not have that night anyway. You do have ten minutes every day.

You make a plan, you commit to it, you act upon it, and then you experience it again. Is there a difference? More than likely, yes. You might not get a 98 on the exam, but you should be able to approach the exam in a more organized and in control fashion. And you will have a clearer idea of how you can learn.

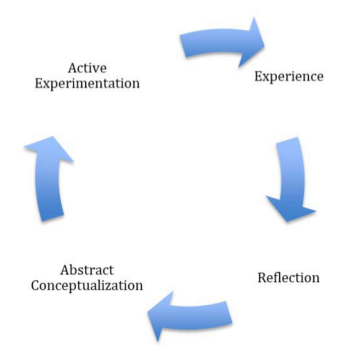

I have just described another theory of learning, one that I particularly like, Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle, pictured below.

As the image shows, this model involves four steps that are cycled through: Experience, Reflection, Abstract Conceptualization, and Active Experimentation. The key part is the reflection. Many people like to say “we learn by experience” but we don’t necessarily. We learn by reflecting on experience and doing something with it. In the model, don’t let the word “Abstract Conceptualization” confuse you. It means, in this case, making a plan for what will work next time.

Reflection is something we all approach differently. Some of us talk to reflect (even to ourselves out loud), some write (I am a writer, but I reflect a lot when I walk my dog every evening), and some just mull it over in our minds when nothing else is holding our attention There is no right way to do it, but there are some questions you should ask yourself, or some territory you should cover in reflection. In order for reflection to be useful, you should focus on what really happened in the experience as well as how you felt about it. You should turn the experience around and see it from other points of view. You should ask, “Is the way I feel about it, am evaluating it, valid, or am I just seeing one side of it?” You can question, why and how did it happened? These are only a few questions that you can use in reflecting. Here is a diagram of questions you can ask about a lecture, film, or speaker.

| Question 1 | Question 2 | Question 3 | |

| What | What is being said? (and not) (understanding) | What does it mean? (interpretation) | What can I do with this information or insight? (application) |

| Why | Why is this important (value) | Why should I accept his position? (logic of his arguments) | Why would I be biased against this position? (questioning my assumptions) |

| How | How did the speaker get to this position/idea view? ( is he or she honest about it) | Could the speaker be leaving something out? (their biases) | How does the speaker support their ideas? (persuade us) |

What I mean for you to take from this is that reflection is useful for you as a self-regulated and self-directed learner (discussed below).

Now, a few words here. First, notice that as I was discussing strategies to improve exam grades, I didn’t say “get a study buddy.” Study buddies or study groups are great . . . IF. What are the ifs?

- You know that the person is a good student. While you might think that student in your history class is cute and you want to get to know them, don’t hide asking the other student out on a date behind studying. He or she may have gotten a 48 on the exam! By a good student I don’t just mean someone with a high grade, however. This person needs to have good learning habits, take good notes, be willing to engage in asking questions, and generally be cooperative. If you don’t commit to serious study and to trying new approaches, such as the ones listed above. Research shows mixed results on study groups because students use it without changing other behaviors, that is, they still don’t read the textbook or go over accumulated notes every day.

- You have to realize this is a study session, not a tutoring session. You have to bring an equal part to the session. If it’s just “I want to look at your notes because I take bad ones,” or “I want you to explain this to me,” you are just using the other person and not helping them.

- You need to study in a good setting, for example, one that is free of distractions, and come prepared (laptop, textbook, paper, etc.)

- You need a plan. It can’t just be, “Well, here we are. What now?” You can first be sure all your sets of notes are complete, and then you can quiz each other, or think up possible questions that will be on the test. Research shows that student who can come up with their own questions and “self-quiz” do better on tests. Plan to take breaks—we really don’t study well in two-hour sessions. The breaks should just be for bathroom and a drink of water and stretching legs, not as long as the session itself!

A second note. Up to this point I have not used the two most important words about learning in college. Those words are “self-directed” and “self-regulated.” Self-directed learning is learning you choose to do, that you are invested in and that you direct. The fact that you are in college should say that you are self-directed, because college is not legally required—we choose to go. Now, I realize that some people go to college for reasons other than choice (that is, someone told them they had to in order to get some kind of reward or avoid some sort of punishment), and those people usually are unsuccessful. I have heard of students who enrolled in college because their parents said, “You either go to work at manual labor, go in the military, or go to college,” and college sounded like the best of the three. That type of student is rarely self-directed.

Self-directed also means that you choose the method of learning and you decide when you have learned it. In this case, college cannot be totally self-directed because, unfortunately, the college expects you to learn a certain amount and show that you have learned in order to get a degree. You have to get certain grades and take certain courses to even stay in school. However, you can still be self-directed by choosing the hours that you take the classes, the professors, the number of hours of classes you take each semester, and the subject matter of the courses.

The point is that your instructors expect a large amount of self-direction from you, because you are an adult now and not required by law to be in their classes. Granted, you may only be in that biology class because two lab science classes are required for your major, but in general you have chosen to be there.

I make this point because it relates to an aspect of self-efficacy called “locus of control.” We do better at tasks, generally, when we have an internal locus of control rather than an external one. In other words, if I am the one making the choices in my life and I recognize that, my viewpoint on learning and success will be quite different than if I think I am just being bossed around by external forces, and therefore a victim. Locus of control means I take responsibility for my life rather than blaming others. If I get a ticket for going 15 miles per hour too fast in a 35 mph zone, I might blame the fact that the police officer was “out for me.” That’s external locus of control. If I own up to the fact it was my foot was the gas and I was going 50, that’s internal locus of control.

On the other hand, self-regulated learning is more about the actual behaviors you engage in as a learner. The concept of metacognition that we mentioned earlier is key here. A self-regulated learner reflects and recognizes what he or she is doing as a learner and seeks to find approaches that will make him or her more successful (and that includes being more economical in use of time and resources). A self-regulated learner is like an athlete who pays attention to her body and outcomes and what they are telling her about her athletic performance.

With all this talk of self-efficacy, self-regulation, and self-direction, it may sound like I am saying that learning is a very individualistic, “lone wolf” kind of phenomenon. That is not what I want to communicate, only that ultimately it does boil down, especially in college, to your own choices and work. However, one of the best parts of college (and one of the downsides of online classes) is that learning is social. Although Bandura originated the self-efficacy concept, it is rooted in his social learning theory, which states that an individual’s actions and reactions are influenced by the actions that individual has observed in others. So, if we have self-efficacy (also called personal efficacy) it’s not because it just sprang from nowhere or we figured it out on our own somehow magically. It came largely as a result of accumulated social interactions and observations over the lifespan

The good news is, though, that even reading this textbook is a social situation for learning, as are the classes you are enrolled in this semester—especially the public speaking class! College allows you to learn in the best of situations—you can learn from others, directed and regulated by yourself.

Of course, one of those people in the situation is the class instructor, and this brings us to the last of the theories. Go back to the beginning of this appendix and read the quotation that starts it, from Forbes Magazine online. (Forbes is a leading business magazine.) Mr. Llopis has put in his own words the essence of Vygotsky’s theory called “Zone of Proximal Development,” which sounds like something from science fiction but is really quite simple and useful.

Vygotsky claimed that we learn only when we are given new tasks that are just outside our ability to do them. If we are given tasks to do that are within our ability, what’s there to learn? Only when we have to stretch outside the “zone” do we learn. Just like an athlete who will try to beat his last time or distance, we have to be asked to do something we cannot do right now in order to learn it. The qualifier is that it cannot be too far outside of the “zone of proximal development,” because the learner will fail and not really be able to figure out why. Ideally, learning tasks must be staged as a series of challenges just outside what you can currently do.

Public speaking instructors do this by making your series of speech assignments longer and more complicated. Your first speech will be short and probably personal; your last speech will be much longer and involve higher-order thinking such as found on the Bloom’s taxonomy. Your history instructor in First Year U.S. History will probably not assign you to write a twenty-page paper. If you are a history major and take the seminar course before you graduate, you will by that time have the skills to write a forty-page, in-depth paper with scholarly sources.

It is your instructors’ and professors’ jobs to structure the classes this way. It may feel like the challenge is too far outside your “zone.” Sometimes, it is; that doesn’t mean you are incapable of the challenge, only that there are some steps in between that you need to do first. In that case, you might need to visit the tutoring center on campus and meet with the professor for extra help.

In my many years of teaching, I have found that sometimes a short conversation with the faculty member clears up a lot of matters. A student might just misunderstand what is being asked of him or her and consequently construe it into a much more difficult task than it is. At other times a tutor or tutorial videos can fill in the gaps. This is often true with math or science concepts that are not that difficult but were missed in your high school education for some reason. The key is not to give up when the task seems right outside your reach. Your mental “arm” is longer than you think. Although we really can’t make our arm longer, we can build synapses in our minds that connect neurons and lead to learning.

This part of the appendix has attempted to explain and inspire. By understanding what really goes on in the learning involved in “higher education,” you will have more tools to reflect on and regulate your learning. I have emphasized that learning is hard work and should be. That does not mean college is all drudgery. You have a unique opportunity to get to know really smart and interesting people in your classes who also want to learn, and in many cases they will be going into the same fields you are, so you have built-in networking colleagues. College is about gaining what is called “social capital” (networks of friends and relationships that you can draw upon later in life) as well as intellectual capital. Instead of coming into class, hiding in the back of the room, burying yourself behind your cell phone until the instructor starts class, turn to someone and say, “Hello. My name is…What did you think about…?”