4.1: Selected Reading

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 88764

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

SELECTED READING

Visual arts are art forms such as ceramics, drawing, painting, sculpture, printmaking, design, crafts, photography, video, filmmaking, and architecture (UVA, n.d.). Many artistic disciplines (performing arts, conceptual art, textile arts) involve aspects of the visual arts as well as arts of other types. Visual arts are for visual purposes in nature; however, visual arts also include applied arts such as industrial design, graphic design, fashion design, interior design, decorative art, calligraphy, jewelry design, and wood craft (The Different Forms of Art, n.d.). In this chapter, the following visual arts forms are explored: drawing, painting, printmaking, calligraphy, photography, filmmaking, computer art, and sculpture.

Drawing

Drawing is a means of making an image, using any of a wide variety of tools and techniques. It generally involves making marks on a surface by applying pressure from a tool or moving a tool across a surface using dry media such as graphite pencils, pen and ink, inked brushes, wax color pencils, crayons, charcoals, pastels, and markers. Digital tools that simulate the effects of these are also used. The main techniques used in drawing are: line drawing, hatching, crosshatching, random hatching, scribbling, stippling, and blending. An artist who excels in drawing is referred to as a draftsman or draughtsman.

Drawing goes back at least 16,000 years to Paleolithic cave representations of animals such as those at Lascaux in France and Altamira in Spain. In ancient Egypt, ink drawings on papyrus, often depicting people, were used as models for painting or sculpture. Drawings on Greek vases, initially geometric, later developed to the human form with black-figure pottery during the 7th century BC (History of Drawing, n.d.). With paper becoming common in Europe by the 15th century, drawing was adopted by masters such as Sandro Botticelli, Raphael, Michelangelo, and Leonardo da Vinci who sometimes treated drawing as an art in its own right rather than a preparatory stage for painting or sculpture (Drawing, n.d.).

Painting

Painting is the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface. The medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush, but other implements, such as knives, sponges, and airbrushes, can be used. Painting taken literally is the practice of applying pigment suspended in a carrier (or medium) and a binding agent (a glue) to a surface (support) such as paper, canvas or a wall. However, when used in an artistic sense it means the use of this activity in combination with drawing, composition, or other aesthetic considerations in order to manifest the expressive and conceptual intention of the practitioner.

Painting is also used to express spiritual motifs and ideas. Sites of this kind of painting range from artwork depicting mythological figures on pottery to The Sistine Chapel to the human body itself. Like drawing, painting has its documented origins in caves and on rock faces. The finest examples, believed by some to be 32,000 years old, are in the Chauvet and Lascaux caves in southern France. In shades of red, brown, yellow and black, the paintings on the walls and ceilings are of bison, cattle, horses and deer.

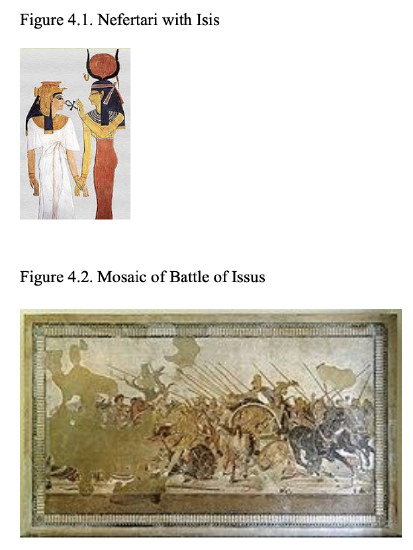

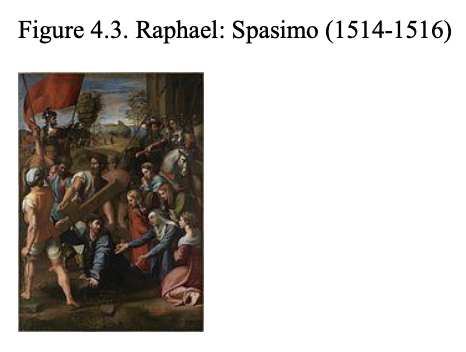

Paintings of human figures can be found in the tombs of ancient Egypt. In the great temple of Ramses II, Nefertari, his queen, is depicted being led by Isis (History of Painting, n.d.) (Figure 4.1). The Greeks contributed to painting but much of their work has been lost. One of the best remaining representations are the Hellenistic Fayum mummy portraits. Another example is mosaic of the Battle of Issus at Pompeii (Figure 4.2), which was probably based on a Greek painting. Greek and Roman art contributed to Byzantine art in the 4th century BC, which initiated a tradition in icon painting.

The Renaissance Painting and Painters

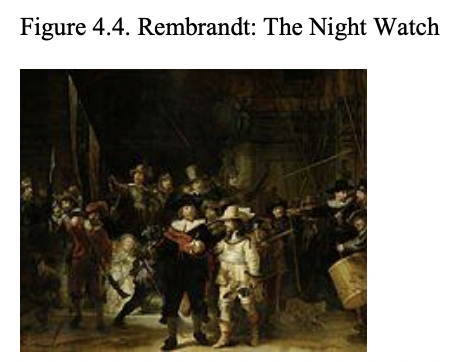

Apart from the illuminated manuscripts produced by monks during the Middle Ages, the next significant contribution to European art was from Italy's renaissance painters. From Giotto in the 13th century to Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael at the beginning of the 16th century, this was the richest period in Italian art as the chiaroscuro techniques were used to create the illusion of 3-D space (Painting in Renaissance Art, n. d) (Figure 4.3). Painters in northern Europe too were influenced by the Italian school. Jan van Eyck from Belgium, Pieter Bruegel the Elder from the Netherlands and Hans Holbein the Younger from Germany are among the most successful painters of the times. They used the glazing technique with oils to achieve depth and luminosity.

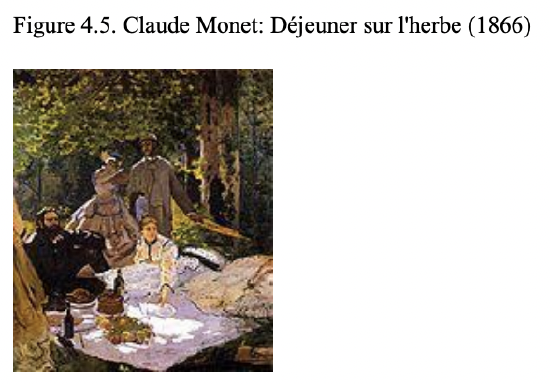

The 17th century witnessed the emergence of the great Dutch masters such as the versatile Rembrandt who was especially remembered for his portraits and Bible scenes, and Vermeer who specialized in interior scenes of Dutch life (Figure 4.4).

The Baroque started after the Renaissance, from the late 16th century to the late 17th century. Main artists of the Baroque included Caravaggio, who made heavy use of tenebrism. Peter Paul Rubens was a flemish painter who studied in Italy, worked for local churches in Antwerp and also painted a series for Marie de' Medici. Annibale Carracci took influences from the Sistine Chapel and created the genre of illusionistic ceiling painting. Much of the development that happened in the Baroque was because of the Protestant Reformation and the resulting Counter Reformation. Much of what defines the Baroque is dramatic lighting and overall visuals (Hills, 2011).

Impressionist Paintings

Impressionism began in France in the 19th century with a loose association of artists including Claude Monet (Figure 4.5), Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Paul Cézanne who brought a new freely brushed style to painting, often choosing to paint realistic scenes of modern life outside rather than in the studio. This was achieved through a new expression of aesthetic features demonstrated by brush strokes and the impression of reality. They achieved intense color vibration by using pure, unmixed colors and short brush strokes. The movement influenced art as a dynamic, moving through time and adjusting to new found techniques and perception of art. Attention to detail became less of a priority in achieving, whilst exploring a biased view of landscapes and nature to the artists eye (Impressionism, n.d.; Impressionism in Visual Arts, n.d.).

Post-Impressionist Paintings

Paintings of Symbolism, Expressionism and Cubism

Edvard Munch, a Norwegian artist, developed his symbolistic approach at the end of the 19th century, inspired by the French impressionist Manet. The Scream (1893), his most famous work, is widely interpreted as representing the universal anxiety of modern man. Partly as a result of Munch's influence, the German expressionist movement originated in Germany at the beginning of the 20th century as artists such as Ernst Kirschner and Erich Heckel began to distort reality for an emotional effect. In parallel, the style known as cubism developed in France as artists focused on the volume and space of sharp structures within a composition. Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque were the leading proponents of the movement. Objects are broken up, analyzed, and re-assembled in an abstracted form. By the 1920s, the style had developed into surrealism with Dali and Magritte (Modern Art Movements, n.d.).

Printmaking

Printmaking is creating, for artistic purposes, an image on a matrix that is then transferred to a twodimensional (flat) surface by means of ink (or another form of pigmentation). Except in the case of a monotype, the same matrix can be used to produce many examples of the print.

Historically, the major techniques (also called media) involved are woodcut, line engraving, etching, lithography, and screen printing (serigraphy, silk screening) but there are many others, including modern digital techniques. Normally, the print is printed on paper, but other mediums range from cloth and vellum to more modern materials. Major printmaking traditions include that of Japan (ukiyo-e). Prints in the Western tradition produced before about 1830 are known as old master prints. In Europe, from around 1400 AD woodcut, was used for master prints on paper by using printing techniques developed in the Byzantine and Islamic worlds. Michael Wolgemut improved German woodcut from about 1475, and Erhard Reuwich, a Dutchman, was the first to use cross-hatching. At the end of the century Albrecht Dürer brought the Western woodcut to a stage that has never been surpassed, increasing the status of the single-leaf woodcut (The Printed Image in the West, n.d.).

In China, the art of printmaking developed some 1,100 years ago as illustrations alongside text cut in woodblocks for printing on paper (Figure 4.8). Initially images were mainly religious but in the Song Dynasty, artists began to cut landscapes. During the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1616-1911) dynasties, the technique was perfected for both religious and artistic engravings (The History of Engraving in China, n.d.) (Figure 4.9).

Woodblock printing in Japan (Japanese: 木版画, moku hanga) is a technique best known for its use in the ukiyo-e artistic genre; however, it was also used very widely for printing books in the same period. Woodblock printing had been used in China for centuries to print books, long before the advent of movable type, but was only widely adopted in Japan surprisingly late, during the Edo period (1603-1867). Although similar to woodcut in western printmaking in some regards, moku hanga differs greatly in that water-based inks are used (as opposed to western woodcut, which uses oil-based inks), allowing for a wide range of vivid color, glazes and color transparency (Figure 4.10).

Calligraphy

Calligraphy is a visual art related to writing. It is the design and execution of lettering with a broad tip instrument, brush, or other writing instruments (Mediaville, 1996). A contemporary calligraphic practice can be defined as "the art of giving form to signs in an expressive, harmonious, and skillful manner" (Mediaville, 1996, p. 18).

Modern calligraphy ranges from functional inscriptions and designs to fine art pieces where the letters may or may not be readable (Mediaville, 1996). Calligraphy continues flourishing in the forms of wedding invitations and event invitations, font design and typography, original hand-lettered logo design, religious art, announcements, graphic design and commissioned calligraphic art, cut stone inscriptions, and memorial documents. It is also used for props and moving images for film and television, testimonials, birth and death certificates, maps, and other written works (Geddes & Dion, 2004; Propfe, 2005).

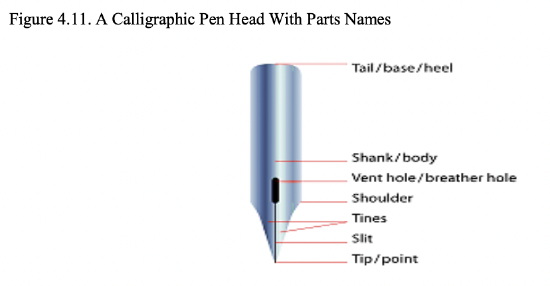

The principal tools for a calligrapher are the pen and the brush. Calligraphy pens (Figure 4.11) write with nibs that may be flat, round, or pointed (Child, 1985; Lamb, 1976; Reaves & Schulte, 2006). For some decorative purposes, multi-nibbed pens-steel brushes-can be used. However, works have also been created with felt-tip and ballpoint pens, although these works do not employ angled lines. There are some styles of calligraphy, such as Gothic script, that require a stub nib pen.

Writing ink is usually water-based and is much less viscous than the oil-based inks used in printing. High quality paper, which has good consistency of absorption, enables cleaner lines (Aesthetic Theory, n.d.) although parchment or vellum is often used, as a knife can be used to erase imperfections and a light-box is not needed to allow lines to pass through it. Normally, light boxes and templates are used to achieve straight lines without pencil markings detracting from the work. Ruled paper, either for a light box or direct use, is most often ruled every quarter or half inch, although inch spaces are occasionally used.

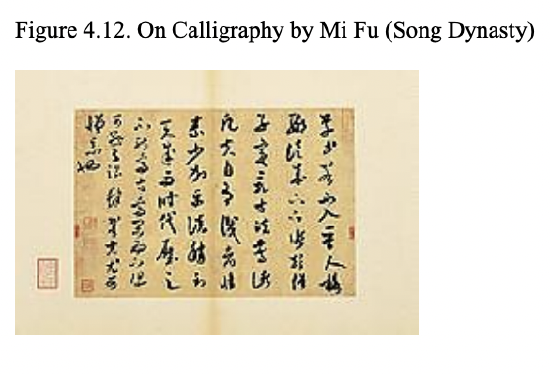

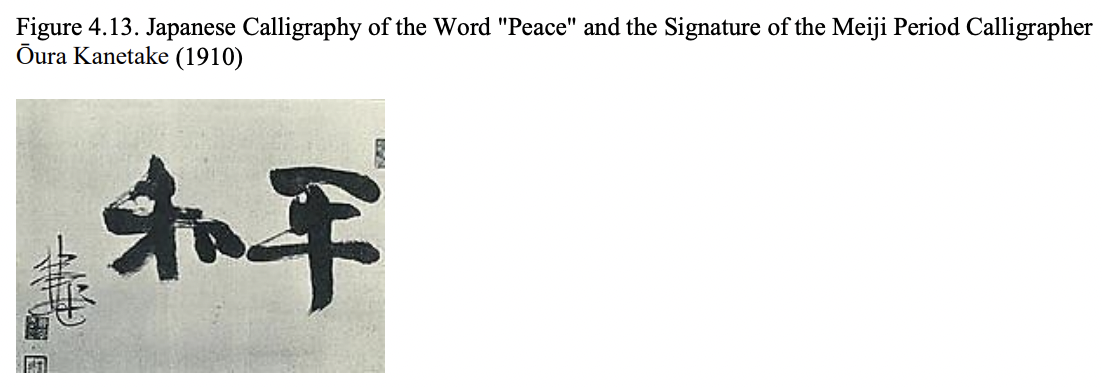

Calligraphic writing with brushes is most found in East Asian calligraphy (Figure 4.12; Figure 4.13). Traditional East Asian writing uses the Four Treasures of the Study (文房四寶/文房四宝): the ink brushes known as máobǐ (毛笔) to write Chinese characters, Chinese ink, rice paper, and inkstone, known as the Four Friends of the Study (Korean: 문방사우, translit. 文房四友) in Korea. In addition to these four tools, desk pads and paperweights are also used.

The shape, size, stretch, and hair type of the ink brush, the color, color density and water density of the ink, as well as the paper's water absorption speed and surface texture are the main physical parameters influencing the final result. The calligrapher's technique also influences the result. The calligrapher's work is influenced by the quantity of ink and water he lets the brush take, then by the pressure, inclination, and direction he gives to the brush, producing thinner or bolder strokes, and smooth or toothed borders. Eventually, the speed, accelerations, decelerations of the writer's moves, turns, and crochets, and the stroke order give the "spirit" to the characters, by greatly influencing their final shapes.

Photography

Photography is the process of making pictures by means of the action of light. Light patterns reflected or emitted from objects are recorded onto a sensitive medium or storage chip through a timed exposure. The process is done through mechanical shutters or electronically timed exposure of photons into chemical processing or digitizing devices known as cameras.

The word comes from the Greek words φως phos ("light"), and γραφις graphis ("stylus", "paintbrush") or γραφη graphê, together meaning "drawing with light" or "representation by means of lines" or "drawing." Traditionally, the product of photography has been called a photograph. The term photo is an abbreviation; many people also call them pictures. In digital photography, the term image has begun to replace photograph. (The term image is traditional in geometric optics.)

Filmmaking

Filmmaking is the process of making a motion-picture, from an initial conception and research, through scriptwriting, shooting and recording, animation or other special effects, editing, sound and music work and finally distribution to an audience; it refers broadly to the creation of all types of films, embracing documentary, strains of theatre and literature in film, and poetic or experimental practices, and is often used to refer to video-based processes as well.

Computer Art

Visual artists are no longer limited to traditional art media. Computers have been used as an ever more common tool in the visual arts since the 1960s. Uses include the capturing or creating of images and forms, the editing of those images and forms (including exploring multiple compositions) and the final rendering or printing (including 3D printing).

Computer art is any in which computers played a role in production or display. Such art can be an image, sound, animation, video, CD-ROM, DVD, video game, website, algorithm, performance or gallery installation. Many traditional disciplines are now integrating digital technologies and, as a result, the lines between traditional works of art and new media works created using computers have been blurred. For instance, an artist may combine traditional painting with algorithmic art and other digital techniques. As a result, defining computer art by its end product can be difficult. Nevertheless, this type of art is beginning to appear in art museum exhibits, though it has yet to prove its legitimacy as a form unto itself and this technology is widely seen in contemporary art more as a tool rather than a form as with painting.

Computer usage has blurred the distinctions between illustrators, photographers, photo editors, 3-D modelers, and handicraft artists. Sophisticated rendering and editing software has led to multi-skilled image developers. Photographers may become digital artists. Illustrators may become animators. Handicraft may be computer-aided or use computer-generated imagery as a template. Computer clip art usage has also made the clear distinction between visual arts and page layout less obvious due to the easy access and editing of clip art in the process of paginating a document, especially to the unskilled observer.

Sculpture

Sculpture is three-dimensional artwork created by shaping or combining hard or plastic material, sound, or text and or light, commonly stone (either rock or marble), clay, metal, glass, or wood. Some sculptures are created directly by finding or carving; others are assembled, built together and fired, welded, molded, or cast. Sculptures are often painted. A person who creates sculptures is called a sculptor.

Because sculpture involves the use of materials that can be molded or modulated, it is considered one of the plastic arts. The majority of public art is sculpture. Many sculptures together in a garden setting may be referred to as a sculpture garden.

Sculptors do not always make sculptures by hand. With increasing technology in the 20th century and the popularity of conceptual art over technical mastery, more sculptors turned to art fabricators to produce their artworks. With fabrication, the artist creates a design and pays a fabricator to produce it. This allows sculptors to create larger and more complex sculptures out of material like cement, metal and plastic, that they would not be able to create by hand. Sculptures can also be made with 3-D printing technology.

Paper Cutting

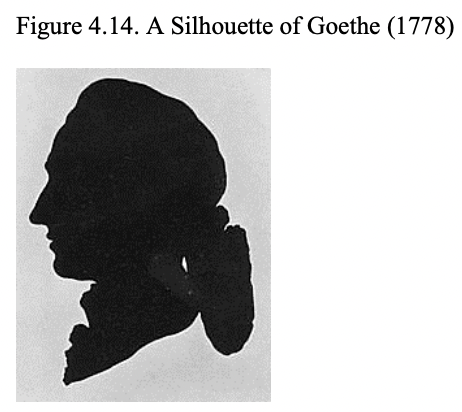

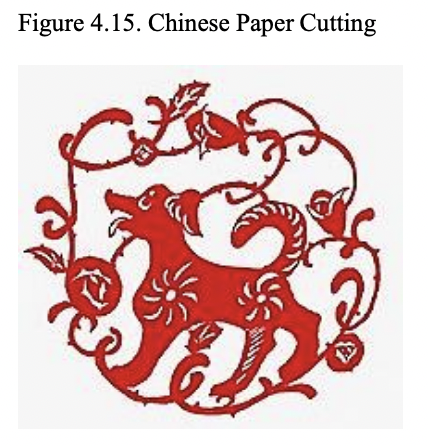

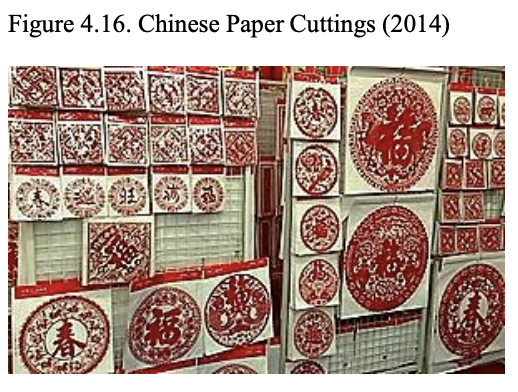

Papercutting or paper cutting is the art of paper designs. The art has evolved uniquely all over the world to adapt to different cultural styles. One traditional distinction most styles share in common is that the designs are cut from a single sheet of paper (Figure 4.14; Figure 4.15; Figure 4.16) as opposed to multiple adjoining sheets as in collage.

Paper cutting, Jianzhi (剪紙), is a traditional style of papercutting in China and it originated from cutting patterns for rich Chinese embroideries and later developed into a folk art in itself. Jianzhi has been practiced in China since at least the 6th Century AD Jianzhi has a number of distinct uses in Chinese culture, almost all of which are for health, prosperity or decorative purposes. Red is the most commonly used color. Jianzhi cuttings often have a heavy emphasis on Chinese characters symbolizing the Chinese zodiac animals.

Figure 4.15. The paper cutting is in a style that is practically identical to the original 6th-century form.

Although paper cutting is popular around the globe, only the Chinese paper cut was listed in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists, which was in 2009 (Chinese Paper Cut, n.d.). The Chinese paper-cutting was recognized and listed because it has a history of more than 1500 years and it represents cultural values of the people throughout China.

Modern paper cutting has developed into a commercial industry. Papercutting remains popular in contemporary China, especially during special events like the Chinese New Year or weddings (McCormick & White, 2011, p. 285).

Origami

Origami (折り紙) from ori meaning "folding", and kami meaning "paper" (kami changes to gami due to rendaku)) is the art of paper folding, which is often associated with Japanese culture. In modern usage, the word "origami" is used as an inclusive term for all folding practices, regardless of their culture of origin. The goal is to transform a flat square sheet of paper into a finished sculpture through folding and sculpting techniques. Modern origami practitioners generally discourage the use of cuts, glue, or markings on the paper.

Origami Paper

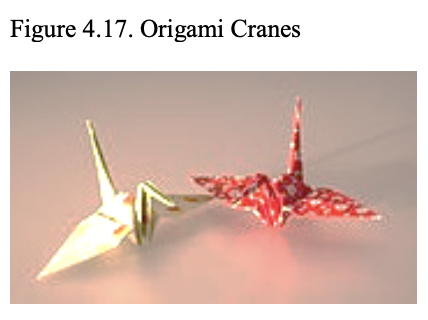

Almost any laminar (flat) material can be used for folding; the only requirement is that it should hold a crease. The small number of basic origami folds can be combined in a variety of ways to make intricate designs. The best-known origami model is the Japanese paper crane (Figure 4.17). In general, these designs begin with a square sheet of paper (Figure 4.18) whose sides may be of different colors, prints, or patterns. Traditional Japanese origami, which has been practiced since the Edo period (1603-1867), has often been less strict about these conventions, sometimes cutting the paper or using non-square shapes to start with. The principles of origami are also used in stents, packaging and other engineering applications (Merali, 2011).

Figure 4.18. A crane and papers of the same size used to fold it.

Ideas of Integrating Visual Arts in the Classroom

Integrating visual arts into the classroom is not as daunting as one may think. Visual arts lend itself to naturalistic, wholistic, and authentic learning. Visual arts integration does not mean integrating art for the sake of another subject; but integrating art for arts’ sake to heighten students’ overall learning experience (Harris, 2011).

To start, think about the fundamentals of visual arts such as line, shape, and color. To teach the vocabulary words of color, the following terminology is suggested: saturation (the amount of intensity a color displays, either very bright or dim), hues (color used in any design in any pixel), tone/value (the amount of lightness in a color placed along a spectrum of black (no tone) to white (highest tone), shades (shades are created by taking a hue and adding pure black to create a new deeper color), and tints (similar except you add pure white to create a new color) (The Science Behind Design Color Theory, n.d.).

To successfully integrate visual arts into the classroom, it is important for the teachers to go outside of own box to new ideas and new learning; it is important to have “cross-disciplinary thinking, collaborative and intentional works, written reflections, revisions, documentation, exhibitions, and critiques-all of which being crucial towards holistic and authentic learning and instruction” (Harris, 2011, p. 21). Visual arts can be integrated into any subject; however, it requires the teacher’s efforts for planning, researching, and reflecting (Harris, 2011).

When visual arts are added to the learning process, content learning becomes more tangible, personal, and meaningful. Visual arts allow students to engage in hands-on learning and inquiry-based learning. Visual arts add to students’ personal expression and creativity in the learning process. In other words, students are engaged in the learning process for deeper levels of learning when visual arts are integrated. There are many activities that can help teachers a jumpstart in integrating visual arts in the classroom. Below are a few activity ideas of integrating visual arts in content areas:

Activity 1: Da Vinci’s Notebook: the teacher shows the images to students and then students search images to brainstorm images for thoughts and themes for the Notebook. The teacher should make sure the images are age-appropriate before letting students surf the web. This activity can be integrated in any subject area (Koonlaba, 2015).

Activity 2: Paper Sculpture Project. Students create paper sculpture projects. This could be integrated in history, writing, language arts, science, and math (Koonlaba, 2015).

Activity 3: Pop Art. It is always very popular with students. The simple imagery is easy for them to imitate. It’s also engaging in content areas (Koonlaba, 2015).

Activity 4: Class Comic Book. Create a class comic book by combining student art pieces and having them work together to write a story with a beginning, a middle, and an ending (Koonlaba, 2015).

Activity 5: Pyramid Art Project. A Pyramid could be painted/drawn/sketched. This could be used to connect art in math and social studies content area.

Activity 6: Poster/Brochure/Advertisement Project. Ask students to create a poster, brochure, or advertisement. These art projects can be great alternative assessment products; they are also a great tool to teach students about graphic design (Hayes, n.d.).

Activity 7: A Work of Art. Ask students to draw or make a collage about a specific topic they are studying in any content area. Cartoons are great to incorporate visual art with current events in social studies (Hayes, n.d.).

REFERENCES

Aesthetic theory of Arabic calligraphy in the Islamic Art. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.calligraphyfonts.info/ae...y-islamic-art/

Child, H. (Ed.). (1985). The calligrapher's handbook. Marlboro, NJ: Taplinger Publishing Co.

Chinese paper cut. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/chinese-paper-cut-00219

Drawing. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20090314...?vendorId=FWNE .fw..dr085000.a

Geddes, A., & Dion, C. (2004). Miracle: A celebration of new life. Kansas City, MO: Andrews McMeel Publishing.

Harris, S. F. (2011). Integrating visual arts into the curriculum. Retrieved from https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/b...RP%20FINAL.pdf

Haynes, K. (n.d.). 12 ways to bring the arts into your classroom. Retrieved from http://www.teachhub.com/12-ways-brin...your-classroom

Hills, H. (2011). Rethinking the baroque. Farnham, UK: Ashgate Publishing.

History of drawing. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.dibujosparapintar.com/eng...e_history.html

History of painting. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.historyworld.net/wrldhis/...HistoryID=ab20>rack=pt hc

Impressionism in visual arts. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.impressionism.org/

Impressionism. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/glo/impressionism/

Koonlaba, A. E. (2015, February 24). 3 visual artists-and tricks-for integrating the arts into core subjects. Retrieved from https://www.edweek.org/tm/articles/2...gthe-arts.html

Lamb, C. M. (Ed.). (1976) [1956]. Calligrapher's handbook. London, UK: Faber & Faber.

McCormick, C. T., & White, K. K. (2011). Folklore: An encyclopedia of beliefs, customs, tales, music, and art. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Mediaville, C. (1996). Calligraphy: From calligraphy to abstract painting (translated by A. Marshall). Wommelgem, BE: Scirpus Publications.

Merali, Z. (2011, June 17). Origami engineer flexes to create stronger, more agile materials. Science, 332(6036), 1376-1377. doi:10.1126/science.332.6036.1376

Modern art movements (1870-1970). (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/mode...tmovements.htm

Painting in renaissance art. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://faculty.evansville.edu/rl29/a...epainting.html

Post impressionism. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/poim/hd_poim.htm

Reaves, M., & Schulte, E. (2006). Brush lettering: An instructional manual in Western brush calligraphy (Revised ed.). New York, NY: Design Books.

The different forms of art. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://arthearty.com/different-forms-of-art

The history of engraving in China. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.chinavista.com/experience...e/engrave.html

The printed image in the West: History and technique. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/prnt/hd_prnt.htm

The science behind design color theory. (n.d.) Retrieved from https://designshack.net/articles/gra...-color-theory/

UVA. (n.d.). What is visual art? Retrieved from http://www.unboundvisualarts.org/wha...ual-art/Propfe, J. (2005). SchreibKunstRaume: Kalligraphie im Raum Verlag (in German). Munich, DE: Callwey Verlag.