1.5: Why is Care and Education with Infants and Toddlers Important?

- Page ID

- 138979

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The rapid growth that unfolds during the first three years of a child’s life is unprecedented and establishes a developmental foundation for future years to build off of. The experiences infants and toddlers have are related to short-term and long-term growth trajectories. Not only are the infant and toddler years associated with school readiness, but the first three years are also a wise investment for long-term academic and developmental outcomes.

School Readiness for Infants and Toddlers?

Until very recently, the majority of work in school readiness has focused on the preschool period. In fact, the term school readiness itself is controversial when applied to infants and toddlers. School readiness often brings about the idea of formal academics such as letters and numbers presented in ways that are not developmentally appropriate for infants and toddlers. However, as the term school readiness became more broadly defined and the research base documenting the important foundations for later learning established during the first three years expanded, families, programs serving infants and toddlers, and policymakers have increasingly accepted that school readiness begins in infancy.

Several organizations have issued guidance and developed resources for programs, practitioners, and families on how to think about and offer services to support the foundations of school readiness in infants and toddlers. For example, in 2013, the National

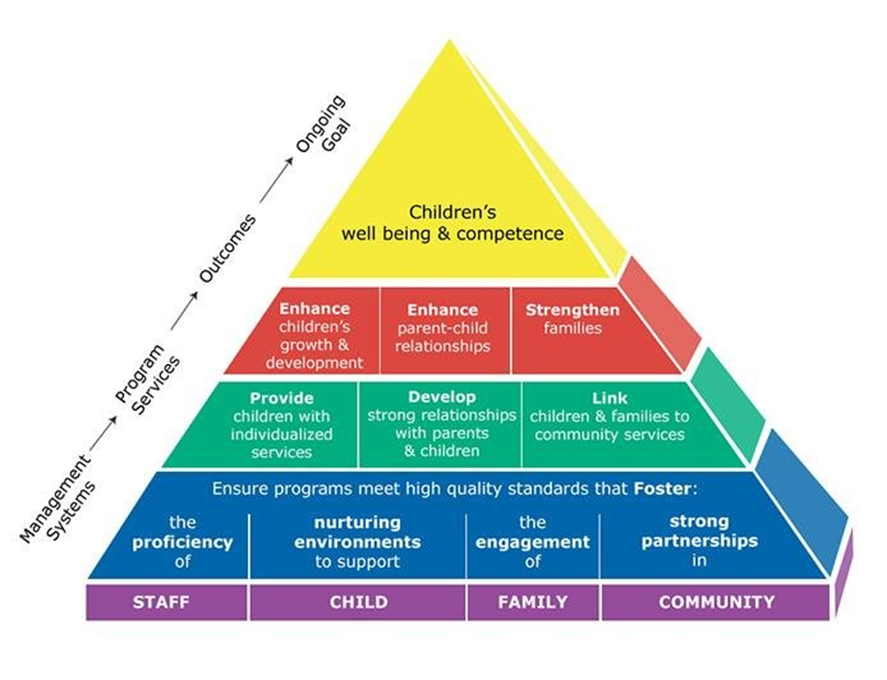

Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) published a book entitled Developmentally Appropriate Practice: Focus on Infants and Toddlers devoted to defining and applying the concept of developmentally appropriate practice for teachers and caregivers working in infant and toddler programs (Copple, Bredekamp, Koralek, & Charner, 2013). The Office of Head Start has also provided guidance to programs through developing the Framework for Programs Serving Infants and Toddlers and Their Families and The Parent, Family, and Community Engagement (PFCE) Framework. Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) presents the Framework for Programs Serving Infants and Toddlers. An important aspect of the Early Head Start framework is the relationship between the provision of high-quality services and children’s growth and development. The quality of early childhood service is multidimensional and encompasses not only characteristics of staff but also the quality of the interactions and relationships among staff members and the children and parents with whom they work. States have also published expectations for infants, toddlers, and their caregivers (National Center on Child Care Quality Improvement, 2019). As of 2019, all U.S. states have developed early learning development guidelines for preschool children (3 to 5 years old), and most states, although not all, have early learning development guidelines that either include or are separate for infants and toddlers. [1] [2]

The infant and toddler period is an opportunity to support young children’s optimal development and to set a positive path for school readiness and life-long success. It is also true that all opportunities involve risk. A risk with applying the concept of school readiness to infants and toddlers is the temptation to funnel practices developed for preschoolers to children under three years of age. To avoid this risk, attention to the unique developmental characteristics of infants and toddlers and purposeful reflection is required to ensure activities and interactions are age-appropriate. [1]

Infant and Toddler Care & Education: A Wise Investment

The experiences infants and toddlers receive during the first three years of life can have a long-lasting impact on their later development, academic achievement and income in adulthood. While there are numerous studies documenting the long-term benefits of investing into the preschool years (Bai, Ladd, Muschkin & Dodge, 2020; Deming, 2009; Fisher, Barker & Blaisdell, 2020; Joo et al., 2020; Knudsen, Heckman, Cameron & Shonkoff, 2006; Nores, Belfield, Barnett & Schweinhart, 2005), more recent studies have revealed that investing into the infant and toddler years has strong, long-lasting benefits as well.

When children attend center-based or family child care programs as infants, they are more likely to graduate high school (compared to dropping out) and less likely to be in poverty as adults (Domond et al., 2020; Gertler et al., 2014; Losier et al., 2021). Attending center-based programs, compared to informal care, such as by a family member, can have a long-lasting, positive impact on a child’s social-emotional, language and cognitive development (Davies et al., 2021; Felfe & Lalive, 2014; Gomajee et al., 2018; Hansen & Hawkes, 2009; Luijk et al., 2015; Orri et al., 2019). Infants and toddlers who attended a center-based program for at least one year saw the greatest social and emotional benefits later in childhood (Gomajee et al., 2018). During the COVID-19 pandemic, infants and toddlers who attended group care programs, compared to those in informal care, had higher cognitive abilities (Davies et al., 2021). In Chile, toddlers who attended center-based care had higher cognitive and language scores, compared to toddlers in informal care (Narea, Arriagada & Allel, 2020; Narea, Toppelberg, Irarrázaval & Xu, 2020).

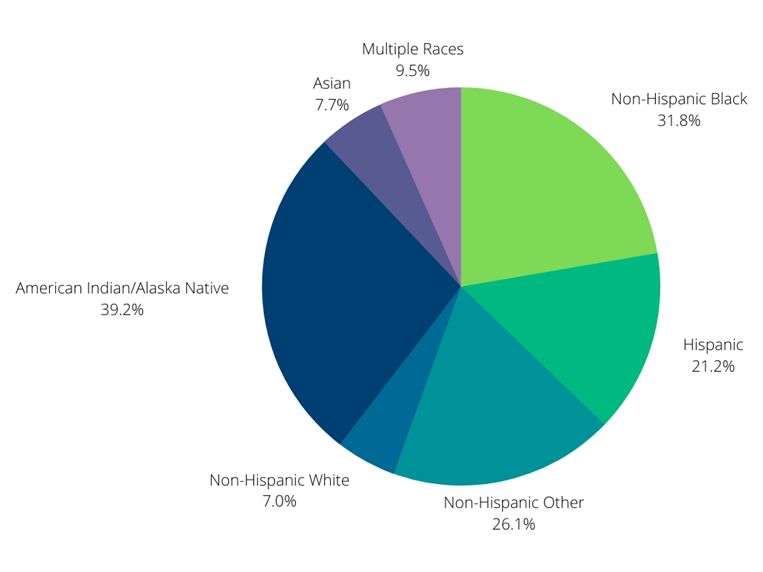

The greatest returns on investments into infancy and toddlerhood may be for the children who are most at risk (Felfe & Lalive, 2014). One risk factor for optimal child development outcomes is low socioeconomic status (SES). SES is a multidimensional construct, combining factors such as an individual's (or parent's) education, occupation, and income (McLoyd, 1998). In 2020, there were 37.2 million people in poverty in the U.S., approximately 3.3 million more than in 2019 (United States Census Bureau, 2012). Approximately 40% of infants and toddlers live in households that are low-income or in poverty (Keating et al., 2021). In California, infants and toddlers of color are more likely to be growing up in poverty (Keating et al., 2021). Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows the percentage of children under three years of age in California, by race, who are living in poverty. Compared to only 7% of White children, 39.2% of American Indian/Alaska Native, 31.8% of Black and 22.2% of Hispanic children are growing up in poverty (Keating et al., 2021). [3] [4]

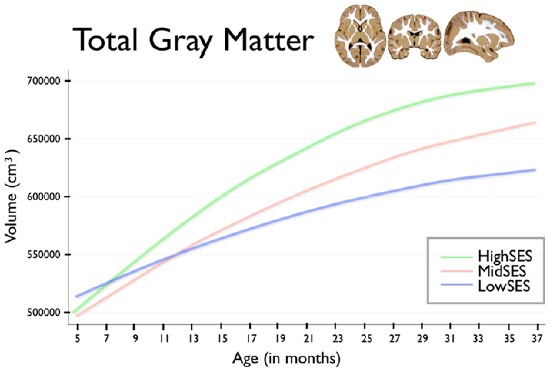

The negative impact SES can have on childrens’ development begins to show an effect during the first three years. Significant disparities in vocabulary and language processing efficiency were evident at 18 months between infants from higher and lower SES families. In fact, by 24 months, there is a six month gap between SES groups in the ability to process language (Fernald et al., 2013). Importantly, these early differences do not fade一stronger language abilities as toddlers are related to stronger language abilities and higher cognitive abilities later in childhood (Gilkerson et al., 2018; Marchman & Fernald, 2008). Already by 21 months of age, toddlers from higher SES families have greater language and memory skills (Noble et al., 2015). [6]

The negative impact SES can have on childrens’ development is a worldwide concern. Latin America is a region that struggles with wealth inequality. After examining young children from five Latin American countries, differences in language skills between the highest and lowest wealth groups emerged by three years of age (Schady et al., 2014). In Ecuador and Colombia, children from higher SES families score higher on language and cognitive assessments and the relationship between SES and ability only grows wider with time (Paxson & Schady, 2007; Rubio-Codina et al., 2015; Schady, 2011). By two years of age, statistically significant differences in IQ had emerged between British children of high and low SES families (Von Stumm & Plomin, 2015). A cross-country study of children from India, Indonesia, Peru and Senegal found that differences in child-development scores emerged as early as nine months of age for children in the highest and lowest SES groups (Fernald, Kariger, Hidrobo & Gertler, 2012). A study from Bangladesh found cognitive differences between SES groups in infants by seven months of age (Hamadani et al., 2014). [6]

The quality of care and education in group care programs during the first three years can be an important factor to reduce the impact SES can have on children’s developmental trajectory (Felfe & Lalive, 2014; Holochwost et al., 2021). Children from low SES families score lower on academic readiness and achievement, unless the children attended a formal childcare program during their first four years of life, including during infancy and toddlerhood (Geoffroy et al., 2010). Infants and toddlers from low SES families exposed to center-based child care demonstrate better reading, writing, and mathematics scores than low-SES children never exposed to center-based programs (Laurin et al., 2015). Children from low SES families who begin center-based care by five months of age have better reading and mathematical skills than infants and toddlers who do not start until eighteen months of age or later. Toddlers who were read to everyday by caregivers had higher reading and math scores as four year olds (Lombardi, Fisk & Cook, 2021). Children who were attending infant child care programs by nine months of age, had greater cognitive abilities later as three year olds (Côté, Doyle, Petitclerc & Timmins, 2013). Although the interaction between SES and child development is complex, research suggests that center-based care is related to greater developmental outcomes due to the quantity and quality of language shared between caregivers and children along with cognitively stimulating experiences (Davis et al., 2021; Lombardi, Fisk & Cook, 2021).

[1] “Early learning and development guidelines” from National Center on Child Care Quality Improvement is in the public domain.

[2] “Income and Poverty in the United States: 2020” from the United States Census Bureau is in the public domain.

[3] Brito & Noble (2014). Socioeconomic status and structural brain development. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 8, 276. CC by 3.0

[4] “Income and Poverty in the United States: 2020” from the United States Census Bureau is in the public domain.

[5] Image by Todd LaMarr is licensed under CC by 4.0. Data is from Keating, Cole & Schneider, A. (2021). State of babies yearbook: 2021.

Washington, DC: ZERO TO THREE

[6] Reynolds (2021). Center-Based Child Care and Differential Improvements in the Child Development Outcomes of Disadvantaged Children. Child & Youth Care Forum. CC by 4.0

[7] Brito & Noble (2014). Socioeconomic status and structural brain development. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 8, 276. CC by 3.0

[8] “Anatomy and Physiology” on OpenStax is licensed under CC by 4.0.

[9] Image from Hanson et al., (2013). Family poverty affects the rate of human infant brain growth. PloS One, 8(12), e80954. CC by 4.0