11.2: Diversity and Equity within the Early Childhood Education Field

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 188794

- Shanti Connors & Ninder Gill

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Diversity

Diversity is “a variation among individuals, as well as within and across groups of individuals, in terms of their backgrounds and lived experiences. These experiences are related to social identities, including race, ethnicity, language, sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, social and economic status, religion, ability status, and country of origin” (NAEYC, 2019, 17).

The key to this definition of diversity is that it moves us away from simply thinking that diversity means being different from someone and appreciating those differences. This definition specifically highlights the experiences that people have based on those differences. Social identities are differences and categories that were and are socially constructed. This means that these categories were and are created and then agreed upon by society and have serious consequences for people’s lives (Sensoy & DiAngelo, 2017).

Below are beginning definitions of the social identity groups listed in the definition.

- Race is a social-political construct that categorizes and ranks groups of human beings on the basis of skin color and other physical features (NAEYC, 2019).

- Ethnicity refers to “people bound by a common language, culture and spiritual traditions, and/or ancestry” (Sensoy & DiAngelo, 2017, p.45)

- Sex is the biological or genetic markers that distinguish male and female bodies and refers to one’s genitals, body structure and is assigned at birth (Sensoy & DiAngelo, 2017).

- Gender is the assigned sex given at birth that have prescribed roles and behaviors and expectations; gender identity is the development of one's self as a male or female in relations to others; and gender expression is the gender that a person presents to the world (Sensoy & DiAngelo, 2017)

- Sexual Orientation is whom a person is sexually attracted to (Derman-Sparks & Edwards, 2020).

- Social and Economic Status refers to the financial and social conditions of a person which determines their access to the institutions and resources of society (Derman-Sparks & Edwards, 2020)

- Religion is a faith and worship into a particular system of beliefs.

- Ability Status includes the ability that children have to do something and acknowledge disabilities including a physical, cognitive, emotional, or neruo-divergent challenge that impacts a person's abilities in some areas of daily living and learning (NAEYC, 2019 & Derman-Spark & Edwards, 2020).

These categories are binary. They are categories that we all belong to and are presented as an either/or to divide and differentiate people. For example, our sex assignment at birth is either male or female and the gender roles attached to our sex are framed around masculine or feminine characteristics. Our sexual orientation is either gay or straight. We are either able bodied or have a disability. Our race is either black or white. However, the 2020 census did collect race data from five groups: White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian or other, Pacific Islander.

To address the binary nature of these categories that differentiate people, NAEYC’s Advancing Equity diversity definition noted that “the terms diverse and diversity are sometimes used as euphemisms for non- White and NAEYC specifically rejects this usage, which implies that Whiteness is the norm against which diversity is defined” (NAEYC, 2019, p.17). This specific clarification is a response to the binary nature of and the social construction of social identity groups and meaning attached to them by society.

Advancing Equity Recommendations for Everyone

When we review the first recommendation from NAEYC’s Advancing Equity statement we are asked to examine the impact and the influence of diversity on who we are as teachers and what and how we teach. We need to have awareness and understanding of our own culture, personal beliefs, values and biases. And in order to do that we have to reflect on our own lived experiences based on our social identities (NAEYC, 2019). As teachers of young children, we are teaching from a specific set of cultural values and beliefs. We have learned those beliefs and values through the cycle of socialization. Through this process we have also learned biases. We have also experienced privilege and oppression based on our social identity groups. To truly understand the impact of diversity on our teaching practices, we have to do some intrapersonal work and examine our own personal and social identity development.

Reflection

How would you describe your social identities as listed in the diversity definition? What are other identities that categorize and differentiate people that are not listed? Do you think our social identities influence how we interact and engage with other people whose identities are different than ours?

Culture, Social Identities & the Cycle of Socialization

Culture is something we all have and is something that we learn. Culture is the experiences, language, values and beliefs that people share at a given time and place. Our cultural ways of being can be as simple and visible as what we have learned to like to eat; what we don’t like to eat; the words we use, language we speak; how we dress; and what music we like to listen too. Culture is also complex and invisible. It is the deeply held beliefs and values we have that influence the daily decisions we make. These beliefs can be about eye contact should look like; touching; relationships with our elders; the way we raise our children; and what role families should play in our lives. There is a lot under the surface that we have learned, and we don’t see or are aware of and those cultural ways of being become automatic.

Ultimately culture shapes and frames how we understand, view, and interact with the world around us and what we learn depends on what cultural and social groups we belong too. We are born into or assigned them at birth, such as race, sex, class, or religion. And they can be cultural and social groups we join or become part of later in life. For example, it is possible to learn a new culture by moving to a new country or area, by a change in our economic status, or by becoming disabled. We all belong to many cultural and social groups. When we have similar cultural ways of being with others, we usually get along better with or feel more comfortable with.

Reflection

Think about the people who are important people in your life. What do you have in common with them? How does this commonality make you feel when you engage with people who have similar cultural ways of being as you? What about with those who are different then you? How do you feel when you engage with those who may not speak the same language as you or eat the same foods as you?

We are socialized into those cultural ways of knowing and being based on the various cultural and social identity groups we are a part of. We have been systemically socialized into those identities (Harro, 2018).

Socialization is the process where we internalize the cultural norms and ideologies of society that we have learned through the institution we interact with i.e. education, church, peers, family, laws, media, business etc. Harro (2018) notes that based on each of our social identities, we learn how to:

- Think about ourselves and others

- How to interact with others

- Understand what is expected of us based on a specific set of social identities we were born into

- Know what the consequences are, if we deviate from what is expected of us

What is important to understand is that these social identities that we are either assigned to, born into, or become a part of later in life predisposes us to unequal binary roles. We are socialized into those roles subtly as well as overtly by our family and institutions (teachers, schools, media, church, work). These roles are prescribed through systematic training that tell us the “appropriate and acceptable ways to be” that identity (Harro, 2018).

In the U.S. the “appropriate and acceptable ways to be” have come from the dominant social groups. We are either part of the dominant groups or marginalized groups. In the U.S. these dominant social groups are men, white people, able-bodied people, middle to upper class people, heterosexuals, and middle-aged people. Subordinate or marginalized groups are women; people of color specifically historically racially oppressed groups; gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender people; people with a disability; seniors and youth; and people living in poverty. Understanding the socialization process and the groups we belong to will help us better understand what we have learned to value and believe but also what we have learned about the groups we do not belong to.

An example of how this socialization process works can be demonstrated by thinking about sex, gender identity and expression. When someone is pregnant, we usually ask them what the sex of the baby is. Will it be a boy or a girl? Depending on what they tell us, we start thinking of names that would we consider boy or girl names. We may also start to think about what kind of toys and clothes to get depending on the sex. When the baby is born, we then begin to engage with the baby and consciously or unconsciously have expectation for them to act and look a certain way. For example, we may remind little girls to not talk loudly, or be too physical in their play and tell them how pretty they look in their new dress. We may tell boys to stop crying and to be strong physically and emotionally. For some children the sex assignment matches with how they identify and want to express themselves being that gender. For some children the sex and gender roles that are expected of them is not what they identify with and how they want to express themselves. However, through the cycle of socialization these roles are enforced by either the child’s family and school, church, and possibly their friends.

Reflection

What social identity groups do you belong to? How did you learn to be a that identity or part of that group? What role did your family, friends, community organizations play in this process of learning about who you were and are now? What role did your teachers play? What messages may we be sending to children about their social identity groups based on how we were socialized?

What is important to remember here is that we were born into or assigned these identities at birth and really have no control over that process and what we learned as children. The cultural norms and values and ways of being were already established. These rules, roles, assumptions were created by the dominant groups and marginalized or subordinate groups were essentially exploited, disenfranchised, and discriminated against (Harro, 2018). Through this cycle society has normalized the dominant groups cultural values, beliefs, and ways of being at the expense of the subordinate groups. This leads to implicit biases that we have learned about other social identity groups. It also leads to systemic bias towards the dominant groups who have unearned privileges and discrimination and oppression of marginalized groups.

Bias

Advancing Equity (2019) defines bias as the attitudes that favor one group over another. Explicit biases are conscious, openly aware of, beliefs and stereotypes that influence one’s understanding, actions, and decisions; implicit bias affects one’s understanding, actions, and decision but in an unconscious, not aware of, manner (NAEYC, 2019). We all have biases. They are learned from our cultural ways of being and through the process of socialization.

An example of explicit bias in the classroom may happen when we openly expect children from specific racial group to be good at sports or be quiet and shy. An example of implicit bias in a classroom would be where all but one or two books have illustrations with only white children and families in them. An example of systemic bias in the classroom may be where the lead teachers and supervisors are white, but the assistants and support staff are people of color or English language learners. Most of the biases we have we are not necessarily conscious of and we have learned to normalize the attitudes and actions of the dominant groups through our socialization process.

The first Advancing Equity (2019) recommendation suggest that we have to recognize that we all hold some type of bias based on our personal background and experiences and socialization. We need to “identify where our varied social identities have provided strengths and understandings based on your experiences of both injustices and privilege” (NAEYC, 2019, 6). Knowing which values, beliefs, and the cultural norms we hold that influence our teaching will help us begin to reflect on the impact we have on children and families that do not have the same values and beliefs.

Reflection

Consider how your values and beliefs influence your teaching decisions. Are those values and beliefs held by the children and families you work with? For example, do you always have the same expectations around sleeping, feeding, potty training children as your families? What biases do you think you may have of others who do not have the same values and beliefs you have? What biases may you have learned about other social identity groups?

Oppression and Privilege

When we reflect on which groups we belong to and learn more about ourselves and others, we will realize that the privileges and oppressions we experience are based on the social identity groups we belong to. Privilege is the unearned advantages that result from being a member of a dominant social identity group. This type of privilege is deeply embedded, and it is often invisible to those who experience it without ongoing deep self-reflection about diversity and equity. An example of this privilege can be the language we use in our programs. If your program is an English-speaking program, then if you speak English it will be easier for you to communicate. Because of your ability to speak English you have access to resources and services that others who do not speak it. If you do not speak English and there are no other languages spoken in the program, then you may struggle with communicating with others.

Oppression is the systematic and prolonged mistreatment of a group of people that results from systemic bias based on their social identity groups. For example, ableism is a systemic form of oppression deeply embedded in society that devalues disabilities through structures that are based on implicit assumptions about standards of physical, intellectual, and emotional normalcy (Derman-Sparks & Edwards, 2020). If we are an able-bodied person, we might not think about making sure our classroom is set up for a child who uses a wheelchair, or a family member who uses a scooter. It may be harder to find tables for children that allow a wheelchair to slide under. When we have not experienced the challenges of a person with a physical disability, the changes needed to adjust our classroom do not come to us as quickly. Usually, they come to us when we have to make those changes because we have a child or family member who uses a wheelchair or scooter.

This is not to say that those of us who have privilege have never experienced challenges and those us who have been oppressed have not experienced advantages. However, when we become more aware of our biases we have learned, the privileges and systemic oppressions we have experienced then we may be able to understand the experiences of others. We can empathize as well as resist and revise our teaching practices based on our understanding of how we have experienced privileges and/or oppressions.

Our early education system is a product of the dominant group’s values and norms in the U.S. When we take the responsibility to become more aware and conscious of whose norms and values we have learned, internalized, and are teaching from, we can assess and evaluate our work with children. In order to be anti-bias we have to know our biases and actively fight against them. In order to be culturally responsive, we have to know what cultural values and beliefs we have that are different than others. Therefore, diversity is not just appreciating and acknowledging differences, it is actively reflecting on our own experiences and identities and how it influences how we are teaching.

Reflection

If biases, privilege and oppression are part of our education system then how can we ensure that all children have access to quality learning experiences?

Equity

When biases and systemic oppression go unexamined or unchecked it leads to harmful and discriminatory experiences for children from marginalized social identity groups. Equity goes beyond “fairness” and provides us with a framework to understand the impact of our biases and oppression on children and families and how we can address them.

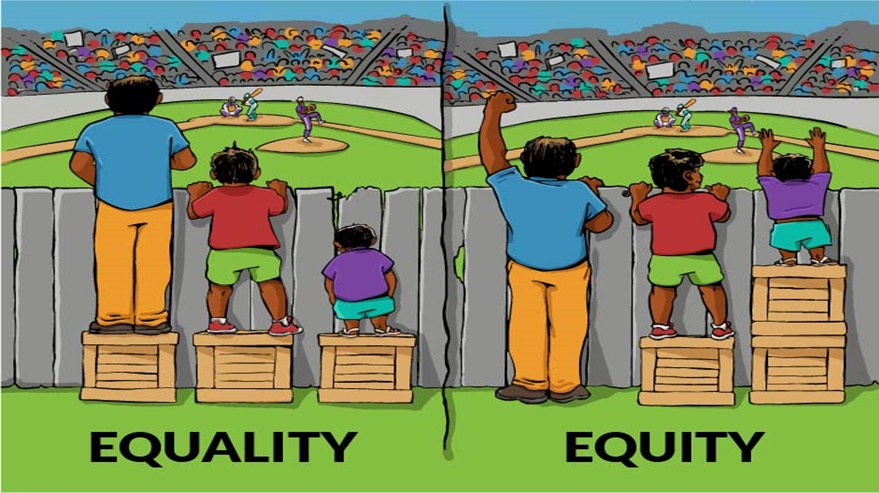

NAEYC’s Advancing Equity (2019) statement defines equity as, “the state that would be achieved if individuals fared the same way in society regardless of race, gender, class, language, disability, or any other social or cultural characteristic” (NAEYC, 2019, p.17). If we have been socialized into unequal roles based on our social identity groups, then we are not truly equal. Attempting to treat everyone the same is essentially not fair. We cannot have equality and fairness until we have equity where children have similar access to resources to support their learning, growth, and development.

The image below provides us with a visual of the difference between equality and equity. Giving everyone the same thing when they are starting from different places would not be equitable.

Reflection

The picture above represents the difference between equality and equity. What does this picture tell you about how we may be using the boxes/crates like in our classrooms and programs?

What supports (boxes/crates) are we providing for children in our classrooms?

Advancing Equity Recommendations for Everyone

Inequities, unfair advantages (privileged) and disadvantages (discrimination and oppression), are built into our systems, they are structural. Advancing Equity’s fourth recommendation tasks us to acknowledge and seek to understand these structural inequities and their impact over time (NAEYC, 2019). As teachers we have to be sure that we do not place blame or fault on a child or family’s character or abilities. Every single child has the potential to learn, thrive and be successful in life. Because of historical and current systemic structural inequities based on social identity groups, children from marginalized groups have been and are disproportionately impacted.

Demographics

The U.S. has always had diverse social and cultural groups. This wonderful and rich growth in diversity continues today. According to the Children’s Defense Fund’s “The State of America’s Children®” 2020 report, 73.4 million children lived in the U.S. in 2018. 50 percent were children of color: 14 percent were Black; 26 percent were Hispanic; 5 percent were Asian/Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander; and <1 percent were American Indian/Alaska Native.

Reflect

Who are the children in your classroom?

What social identity groups do they belong too?

However, the statistics below provide a glimpse into what structural inequity look like for children in our country.

- 16 % of America’s children were poor in 2018–a total of 11.9 million children–and children of color were disproportionately poor (Children’s Defense Fund, 2020).

- Poverty is one of the biggest threats to children’s healthy development. There are 11,752,892 children in the U.S. between the ages of 3 and 5.9% of them in deep poverty where families of these children have incomes below 50 percent of the federal poverty line, or less than $10,289 for a family of one parent and two children (National Center for Children in Poverty, n.d.)

- $88,200 was the median income for white families with children compared with $40,100 for Black and $46,400 for Hispanic families in 2017 (Children’s Defense Fund, 2020).

- Children from families with higher socioeconomic status (economic status, education, occupation) were likely to enroll in higher education institutions then those from lower SES families (Long, 2007).

To help us better understand equity, we will specifically examine race and what racism looks like in early childhood education. NAEYC’s Advancing Equity (2019) defines race as a social-political construct that categorizes and ranks groups of human beings on the basis of skin color and other physical features. As we learned earlier from the definition of diversity and from the cycle of socialization, race is a social identity that confers privilege to one group and discriminates against another. Racism is defined as a belief that some races are superior or inferior to others and it operates at a systemic level through deeply embedded structural and institutional policies that have favored Whiteness at the expense of other groups (NAEYC, 2019).

Throughout history of public and early childhood education children have been discriminated against because of their race. Children of slaves were not allowed to attend schools and indigenous children were removed from their homes and sent to boarding schools. Not all children are starting with the same resources or supports because of historical and current bias and oppression in our institutions. BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of color) children and families are part of our classrooms and programs. Earlier we reflected on bias, privilege and oppression. Looking at data about preschool expulsion and suspension rates we can see how our implicit biases about a child’s race are contributing to systemic oppression:

- Gilliam (2005) in his initial Yale study found that expulsion and suspension rates are higher in preschool programs then in K-12 schools.

- The U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights (2016 a, b.) confirmed that these rates were disproportionately high for Black children where Black children make up 18% of preschool enrollment, but 48% of preschool children suspended more than once.

- Gilliam (2016) and Kunesh and Noltemeyer (2019) found that race and implicit bias seem to be contributing factors to the higher expulsion and suspension rates for black and brown children specifically boys.

Furthermore, here in Washington State, the Department of Children, Youth and Families found children of color are underrepresented in the percentage of children entering kindergarten with the skills they need to be successful. Children and youth of color enter and remain in the child welfare system at greater rates. Youth of color are also disproportionately represented in the juvenile justice system (DCYF, n.d.). Teachers are a part of creating this data. We have to consistently be considering children’s diverse identities and how our own biases may be contributing to these systemic issues.

Achievement and Opportunity

All children can achieve. All children have the capacity to learn and develop to their fullest potential when they have the opportunities to do so. But due to bias that exist in individual teachers, in our programming and educational system, not all children are set up for success. Milner (2012) identified this as an opportunity gap. It is important for us to understand this distinction. Structural inequities adversely impact BIPOC children; however, it is not something inherently in them or related to their ability and capacity to learn. Again, all children will achieve if the opportunity to do so exist. As teachers we have to be creating those opportunities.

The fourth Advancing Equity recommendation reminds us that we do this work by looking deeper at our own expectations, practices, and curriculums especially when outcomes vary significantly by social identities (NAEYC, 2019). Authentic observations and assessments can assist teachers in identifying aspects of their work that could be adjusted to create more equitable learning experiences, and family support. Teachers need to see each child as a capable learner and develop culturally responsive curriculum and individualized learning experiences to create opportunities for growth and development. We have a responsibility to set the stage so that all children have opportunities to learn, grow and develop to their fullest potential.

We have learned and inherited our biases about race, socio-economic class, sexual orientation, gender expression and identity, ability and disability, language, national origin, indigenous heritage, religion, and other identities. Ongoing critical reflection on our biases and our social and cultural context and how we may be contributing to systemic inequities is necessary for achieving better outcomes for all children, especially for those who are from historically and systemically, marginalized, and oppressed groups.

Reflection

How are children and their families in your classroom impacted by bias and systematic oppression?

What are some things you are doing to ensure that all children feel they belong in your classroom?

What changes can you make in your classroom and curriculum to create equitable learning opportunities?

Inclusion

The study of inclusion involves how we can intentionally create equitable learning opportunities into our teaching, curriculum, and programs with a commitment to continuous learning. Inclusive teaching strategies engage each child to feel like they belong and help them to participate in the learning experiences with the rest of the group.

NAEYC Advancing Equity defines inclusion as “the embodiment of the values, policies, and practices that support the right of every infant and young child and their family regardless of ability, to participate in a broad range of activities and context as full members of their families, communities and society” (NAEYC, 2019, p. 18). To be inclusive means to include everyone, and full inclusion seeks to promote justice by ensuring equitable participation of all children. To be inclusive we also need to know who we may be unconsciously excluding.

When early childhood educators take the time to truly get to know children, and their abilities, they can design learning environments that are welcoming to all children. It is important to consider aspects that include the children’s culture, linguistic background, and developmental ability when setting up an inclusive classroom. Effective and developmentally appropriate teaching strategies for inclusion involve building nurturing relationships, authentic observations, scaffolding learning experiences, adjusting support, and collaboration.

Advancing Equity Recommendation for Everyone

There are several recommendations that can support our ability and capacity to work towards inclusion where all children feel like they belong. The second NAEYC Advancing Equity recommendation for everyone tells us that we need to recognize the power and benefit of diversity and inclusivity and recommendation three asks us to take responsibility for biased actions, even if unintended, and actively work to repair harm (NAEYC, 2019, p. 6). In our classrooms, children are learning about the world around them. Developmental theories and brain research tell us that the first 8 years of a child’s life is one of exponential growth. Children are curious and engaged in what we share during circle time. They are active and excited when they participate in our planned or spontaneous table activities. During this time of active cognitive learning, children are also learning about themselves and others as well. Children in our classrooms are not only working towards meeting developmental milestones but they are also being socialized by their families, teachers, and the communities they live in. They are beginning to learn about the cultural norms of their family as well as the social norms that we have in our classrooms and those of society. We are an intimate and integral part of a child’s social and cultural growth and development. Whether we know it or not, we may be contributing to the deep inequities that exist for children and their families because of their social identities. It is imperative and necessary for us to consider ways that we can be more inclusive in our work.

Acknowledge, Discuss and Plan

Creating welcoming and inclusive classrooms requires educators to put forth an ongoing effort. When we become more comfortable with social diversity, we will become more comfortable talking to children about differences that children will notice. If we don’t acknowledge a child’s observation in a positive way, then it gives them the impression that the difference is a problem or something negative.

Think about taking the following steps when a child sees something that is different in another child or their families.

- Don’t ignore it. Our initial acknowledgement can be a simple positive affirming statement. For example, a child’s may ask why their friend has two dad’s and no mom’s. A simple positive acknowledgment of this observation is to affirm that the child does have two dad’s and that there are so many different kinds of families.

- Continue the discussion. We should continue the discussion depending on our comfort level by using open ended questions and examples to share about affirming the differences and normalizing them to the child. If we are uncomfortable continuing anymore discussions, then we can revisit it at another time when we feel more prepared.

- Plan for integration. This leads us to the third step where we can plan for a purposeful introduction or integration into our lesson planning and materials we have in our classroom.

Reflective practices that involve consideration about children’s abilities, languages, culture, and temperaments will guide teachers to adjust their teaching approaches to create inclusive learning environments. This type of reflective approach focuses on the uniqueness of each child, and their individual needs and social diversity. Following are brief descriptions of inclusive practices and approaches you can apply to your teaching.

Critical Reflection

Critical reflection is required to help us assess our thinking, judgements, and actions in the classroom. Self-reflection is a strategy that teachers should use to stop, step back, pause and think about their work and assess to make changes or affirm what is working well. Sometimes self-reflection happens in the moment in the classroom after a planned activity or it may happen at a time when you are not in the classroom. Critical self-reflection is a process where we stop and consider why we did what we did, how we did and specifically ask if there were any biases in our decision making.

Culturally and socially, many of the developmental theories we have relied on were researched by white men with children and families who spoke the same language, lived in similar homes and with similar traditional family structures, who were part of the dominant (white) culture at that time. Having the ability to reflect on information that is current and culturally responsive will help us engage with diversity, equity, and inclusion in your work with children. Learning more about growth mindset, trauma informed care (ACES) and language development are places you can start to develop an understanding of current developmental needs and supports.

Anti-Bias Approach

Ultimately the goal of anti-bias education is to be conscious of and actively fight against biases we have about others and that exist in the institutions we work and live in. Derman-Sparks and Edwards (2020) explain the anti-bias approach as an approach in early childhood education that explicitly works to end all forms of bias and discrimination towards children by those who care, teach, and guide them.

Derman-Sparks & Edwards (2020) outline four goals of anti-bias education that will nurture the development of the whole child so they can:

- demonstrate self-awareness, confidence, family pride, and positive social identities

- express comfort and joy with human diversity, use accurate language for human differences and form deep, caring human connections across diverse backgrounds

- increasingly recognize and have language to describe unfairness (injustice) and understand that unfairness hurts

- and have the will and the skills to act, with others or along against prejudice and/or discriminatory actions

For us to meet these goals of identity, diversity, justice, and activism, we need to learn about the social, cultural, economic context of the child, their family and of ourselves. As we discussed earlier in this chapter, we all have biases that we learned through the cycle of socialization. We also have our own social, cultural, and economic context that influences how we work and teach. Becoming more conscious of our biases through critical reflective work will help us determine how we learned to know what we know and do what we do.

To better assess our awareness and knowledge below are some activities that can be done.

- Classrooms. Look around your classroom and reflect on the materials you use to teach children. What social identities are represented in your books and dramatic play area? What kind of pictures are up in your classroom? Who is visible and who do we not see?

- Books for Children: Assess your books for bias by using the Guide for Selecting Anti-Bias Children’s Books written (Derman-Sparks, n.d.).

- Self-Assessments: Consider completing self-assessment about the own social identity groups you belong to. How were you socialized into those identities? What did you learn about groups that you belonged too and what did you learn about groups you did not belong too? Reflect on where you may have experienced privilege and/or discrimination (Derman-Sparks & Edwards, 2020).

- Books for Teachers: Read more! Start with NAEYC’s Advancing Equity in Early Childhood Education Position Statement (NAEYC, 2019). Specifically look over the recommendations for early childhood educators. Derman-Sparks & Edwards, Anti-Bias Education for Young Children and Ourselves (2020) provides a thorough introduction to anti-bias education in early childhood education.

- Self-Education: Take classes on Anti-Bias Education, Diversity & Equity, Inclusion to continue to learn and build your knowledge and awareness. Another thing to consider is finding ways to expand your knowledge of diverse experiences and perspectives without generalizing or stereotyping about others who are different from you (NAEYC, 2019). Ted Talks are an excellent way to hear powerful and empowering authentic stories about systemic oppressions and bias. There are some suggestions in the website to review following the references at the end of this chapter.

- Intent vs Impact: Remember good intent does not always lead to positive impact. When you commit a biased act, be ready and willing to be accountable and to take that opportunity to learn rather than being defensive (NAEYC, 2019).

- Book Clubs: Think about starting a book club focusing on diversity and equity with your co-workers or with your friends and families. Or even with the children!

This is a journey and requires continuous learning for all of us. Take time to regularly reflect and revisit the aspects listed above, so you can create an equitable and inclusive early learning setting for children to thrive in. Invite your co-teachers to examine and discuss aspects with you. This type of collaborative work supports raising awareness of issues and developing an anti-bias approach.

Anti-Racist

If the stories we are learning from and teaching with are from the dominant white culture perspective, then we have to move beyond the anti-bias approach and also be anti-racist. Children are constantly internalizing the messages conveyed in their environments. As we previously discussed, BIPOC children are being disproportionately impacted by our education systems. A recent study found that children as young as 5 rated images of black boys less favorably than images of white boys and girls, with images of black girls falling in the middle (Perszyk et al, 2019). As teachers we are also socializing children into the dominant cultural norms and values. It is critical that we reflect on what we are teaching children that may not be visible to us.

Furthermore, Dr. Shulman (2020), President of the American Psychological Association, stated that we are living in a racism pandemic. This racism “pandemic” leads to a number of psychological, physical issues and historical trauma (Shulman, 2020). The impact of racism emphasizes the urgent need for each early childhood educator to engage in anti-racist work. This work will require us to examine our own racial biases we may have based on our own socialization process. Anti-racist work will look different for each person and teachers in each of our classrooms, and our teaching approaches. We all can actively fight against racism. Some educators might say that they do not see color, however we want to avoid this color-blind approach. When we see color, we truly see children, and welcome the diversity that each child brings.

We will have to actively engage in learning more about what it means to be an anti-racist as well. Dr. Kendi (2019) points out that the opposite of being a racist is not just being not racist, it is being an anti-racist, where we are actively fighting for racial equity. It means examining our own beliefs about what racial equity is. Through evaluation and reflection, we can dig deeper in our own socialization process and check for beliefs and ideas of others based on our and their race.

Working with Families

As we learn more about ourselves, we will begin to realize the social and cultural systems that our families lived and worked in influenced us as children and now as adults. This same process is something we are part of for the children and families we are working with. As teachers we have an opportunity to disrupt the socialization process that perpetuates the discrimination and marginalization of social identity groups.

It is important that we move away from the binary classification of social identities. We have learned to value and espouse the either/or way of thinking about others but why can’t we be an and/both? When we begin to shift our thinking to an and/both perspective we allow for more space to integrate the diverse needs and supports our children and families need. We can use a child’s home language in the classroom and use English to support their language development. Why can’t we boys and girls wear dresses in our classroom and be able to rough and tumble and assertive in their play?

Home Environments

In early chapters, we learned how important home environments are for each child and how their home environments may be very different from early learning environments. Children may be living and thriving in a single parent household; a multi-generational household where other family members are an integral part of the home; or children may be homeless and living in transitional housing. This is just a few ways that diversity in family structure can look for the children in our classrooms.

Connecting with Families

Learning more about our families does not mean that we have to integrate or engage with all that they may do for their child. But we can begin to consider ways to support the child based on what they are learning from their family and what we are teaching them. Think about the ways you connect with families.

- How do we get to know our families, and how they raise their child at home? What are some ways that incorporate the cultural ways of being of the families into your program?

- How do we reflect or consider a child’s home environments impact on the child’s way of being in our classrooms?

- What networks of support does the family have outside of the home? How can we create a supportive network within the early learning program?

- How are we creating a sense of emotional and physical safety for the family? For example, if a family is undocumented then the way they engage with the school will depend on their level of safety they feel with the teachers and the school. This will be something that impacts the child.

- How are we integrating the funds of knowledge that children and families already have into our classroom?

Ultimately, to create responsive equitable learning opportunities we must fully understand the lived experiences of the family and the child outside of our classroom. When we reflect on how a child is influenced and impacted by the environments that their families have to navigate to function and survive, we can create equitable opportunities for the child and the family because we have a better understanding of the barriers that the family is experiencing.

Culturally Responsive Teaching

When we integrate culturally responsive teaching into practice we are moving to another level of critical reflection. We not only see how our social identities influence our decision-making we also acknowledge and find ways to teach using the cultural context of the children in our classroom. Culture is increasingly understood as inseparable from development (Rogoff, 2003). Therefore, it is important to ensure cultural continuity, where the child’s home culture is reflected in the classroom and is not invisible. Many marginalized social identity groups are invisible in our classrooms and teaching materials.

Zaretta Hammond (2018) writes about the pliability of young children’s brains. Her focus was mostly on older children, but it is a reminder again that we set the stage for how children see and feel about themselves and where they fit into the classroom environment. There are three strategies we can use right now with children and some of us are doing them already.

- Culturally responsive teaching in practice can be as simple as making learning fun with interactive games that focus on social and verbal interactions, instead of just sitting and listening (Hammond, 2018).

- Children learn by doing, so adding a game to the learning makes it more engaging. Teachers can facilitate group activities in which children work together to create a story, or mural together. We could create a guessing game using felt boards when teaching about body parts. Give children felt pieces that represent different parts of the body and have them guess what parts they use to smell something they cook at home.

- Another strategy is to make it a social experience (Hammond, 2018). Think about how we lead circle time, do we allow children to share and talk during our reading of a story or teaching of a specific lesson?

- Do we make time for children to talk with each other about what they are learning? Consider asking children to share their favorite smell, family activity, food they eat together at home, or play a song that they listen to at home.

- A third strategy is to add stories (Hammond, 2018).

- We can invite families to share or make up stories with their children about smells? Have elders come and tell stories in the classroom during circle. Instead of reading books listen to stories families have recorded. This also helps us see how using play could be a culturally responsive strategy.

Ultimately, culturally responsive teaching occurs when we integrate teaching strategies that are centered from the children and their family’s culture. This does not mean we have to know about all the cultures of our families and how they live outside of the classroom. As the fifth NAEYC Advancing Equity (2019) recommendation mentions we just need to be willing to be open to learning and commit to learn based on our experiences with children and their families. When we are open to learning more about children and families, we will build connections and partnerships that will support children’s development. These connections demonstrate that we welcome all families and strive to incorporate children’s cultures into the learning experiences.

Final Thoughts

This chapter discussed aspects related to diversity, equity, and inclusion in early learning settings. The details within these topics included societal issues, identities, bias, and cultural identity development. The information presented influences that can impact our teaching and program practices, along with ways to engage in anti-bias work. Diversity is more than just being different from someone. It requires a commitment to learn about our own diversity and how it influences our teaching. Equity is more than trying to treat everyone fairly. We have a responsibility to understand that not everyone has had the same opportunities, so we have a responsibility to ensure that all children have access. Inclusion is not just making every feel welcome. It requires us to take an active role in engaging and integrating children and their families' diversity into our programs intentionally.

We hope that this chapter will motivate and inspire early childhood educators to learn more about the children and families in their programs and strive to work with them in a culturally responsive way. Every interaction we engage in with children can influence their memories, cultural and social development, and ideas about how they fit into this world. We have the responsibility to ensure that every single child feels welcomed as a valuable part of the learning community. In order to ensure that children meet their fullest potential, it is vital that we continue to study, reflect, and act to address diversity, equity and inclusion.