Descriptions of Families

Here are descriptions of the types of families listed in Chapter 8.

Dual parent family

We often thing about this as a mother and father raising children. However, in thinking about the the diversity of families this could include same sex parents as they are also raising children together.

Single parent family (either by choice or through divorce)

This could be a male or female parent who either wants to be a parent and does not have a partner to create a child with or is raising children on their own due to divorce. Often, we think of single parents as female, but today as we continue to form acceptance of family structures, they are males who are also choosing to form a family on their own or raise their children (from divorce) on their own.

Grandparents or other relatives raising children (relatives can also be non-related family members who are close to the children)

Children whose parents are not able to care for them (for whatever reason), may be raised by their maternal or paternal grandparents or may be raised by extended family members including those family members that are not related biologically.

Teen parents

Today it is more acceptable for teens who become pregnant to raise a child. Sometimes they may do this together or separate. Sometimes they may do this with the help of their families. Teens who become pregnant while still in high school are often able to return to school and there are programs on high school campuses where teens may bring their child. They may receive parenting classes in addition to their high school curriculum.

Adoptive families (including transracial adoption)

Families who are not able to conceive a child or carry a child to term may choose adoption as a way to form a family. While this tends to be most common, there are families who consciously choose adoption over procreation as well as decide to add to their family through adoption. In any case, forming a family through adoption is a choice not taken lightly. There are many options in forming your family through adoption. You can choose to have an open or closed adoption. Open adoption refers to having a continued relationship with the birth parent(s) to just knowing who the birthparents are and everything in between. Closed adoption means that the family does not have access to birthparent(s) information. In addition, families may choose to adopt a child of the same race or of another race.

Foster families

Children placed in temporary care due to extenuating circumstances involving their family of origin may be placed in homes that are licensed to care for children. The adults who foster these children must go through strict protocols in order to care for these vulnerable children. The most common name for this arrangement is fostering, but you may also hear them described as resource families. In these cases, it is the intent to reunite the children with their family of origin whenever possible. When this is not possible, the children are placed in the system for adoption. The foster family may decide to adopt the children or adopted by another family. It is always the intent to find a permanent arrangement for children whenever possible, as we know that stability has better outcomes for children.

Families with Same-sex parents

Same sex couples, whether two men or two women, may choose to form a family and raise the children together. There are many options available when deciding to form their family. They may adopt, they may use reproductive technology, and they may use egg or sperm donors. In the case where two women are choosing to form a family, one of them may become pregnant and give birth to their child. According to recent research into children raised by same sex parents, there is evidence to suggest that since these children are planned, they often have better outcomes than originally was believed.

Bi-racial/Multi-racial families

These include families with children raised by parents from two different races, including parents who may be bi-racial themselves. This also includes multi-racial families. Society is becoming more acceptable of diversity within families, which provides children with better outcomes.

Families with multi-religious/faith beliefs

This includes families with children raised by parents who have different religious faith/beliefs. They may choose to raise their children with neither religion, either religion, or both.

Children with an incarcerated parent(s)

This includes families where one or both parents are incarcerated. This can be complicated for the family as the parent may spend some time away and then return home. While the parent who is incarcerated is away, the family structure changes. Each time the parent goes away and comes back adds to this confusion. Sometimes, children whose parent(s) are incarcerated may live in foster care while their parent is away and be returned to the parent upon their release, if it is safe for the child to do so.

Unmarried parents who are raising children

Today, many parents are deciding not to marry and raise children. The only difference is that they do not have a legal marriage license; however, their family structure is the same as dual parent families whether opposite sex or same sex.

Transgender parents raising children

This refers to two ways in which children may be raised by a transgender parent or parents. A parent may transition after already having children with someone of the opposite sex or they may transition prior to having a child and decide they want to parent.

Blended families

A blended family can be two different parents that come together each bringing their children from a previous relationship with them. Sometimes the parents that come together with children from a previous relationship may also decide to have a child together.

Multigenerational Families

These are families where multiple generations either live together in the same household or nearby. In America, this was a familiar practice during our agricultural boom. In other countries, this is an accepted practice, especially in Native cultures.

Families formed through reproductive technology

Today we have sophisticated medical advances to help parents who are infertile to become pregnant and give birth to their biological child as well as to use the biological material from someone else and carry that fertilized embryo to term. The variety of reproductive technology available to families is quite expansive. This is often at a huge financial cost to the families, as most medical insurance companies do not cover the medical expenses of infertility.

First time older parents

Today it is becoming more common for men and women to have children in their 30’s, 40’s, and even older.

Families who are homeless

We know that some children are raised without a stable home. The family may be living in their car, living in a hotel, a homeless shelter, or living in multiple dwellings also known as couch surfing. Families experiencing homelessness may be due to the loss of a job/steady income, being employed by making minimal wages that do not provide the means necessary to sustain housing (and other basic necessities), or other issues that may complicate the family’s ability to sustain a stable place to live. Families do not always share their homeless status as there is often shame and embarrassment that society places on these families.

Families with children who have developmental delays and disabilities

This refers to families who have a child or children with developmental delays and/or disabilities. These delays/disabilities are varied. There also may be typically developing children in the family as well. This often places a burden on families, not only because of the time needed to care for a child who is not typically developing, but because society often misinterprets children who display behaviors that may be viewed as challenging.

Families raising their children in a culture not their own and in which English is not the primary language

This refers to families who may have immigrated here and whose children were either born in their country of origin or born in the United States. This duality of cultures can create challenges for the child and their family if societal expectations are that the family enculturate to the dominant culture. This results in children feeling shame about their family when they should feel pride in their family of origin.

[1] Gordon, A. M., & Browne, K. W. (2016). Beginning essentials in early childhood education . Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. Laureate Education INC., The History and Theory of Early Childhood Education [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from http://mym.cdn.laureate-media.com/2dett4d/Walden/EDDD/8080/01/mm/history_theory/WAL_EDDD8850_HT_EN.pdf , Image by Author is licensed under CC0 Public Domain , Image (Orbis Pictus) is in the public domain, Image is in the public domain., Image by Chris Bertram is in the public domain., Image is in the public domain.,

[2] Image is in the public domain., Image by Nathan Hughes Hamilton is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ., Image is in the public domain., Image by Stefano Lubiana is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ., Image is in the public domain ., Image by Spudgun67 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ., Image by Dodd Lu is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 ., Image is in the public domain., Image by Dragos Gontariu is from Unsplash .,

[3] Image is in the public domain., Image by delfi de la Rua from Unsplash., Image by Drümmkopf is licensed under CC BY 2.0 .

[4] T. Berry Brazelton. (2018, June 11). Retrieved from https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/T._Berry_Brazelton ., David Elkind. (2018, October 15). Retrieved from https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Elkind ., Bio. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.alfiekohn.org/bio/ ., Dr. Dan Siegel - Home. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.drdansiegel.com/ ., Childtrauma. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://childtrauma.org/ ., Image by Ninjaassasinman is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ., Image by Leo Rivas from Unsplash., Image by David Stirling is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ., Image by Lesly Juarez from Unsplash., Image by Toimetaja tõlkebüroo from Unsplash.

[5] Gordon, A. M., & Browne, K. W. (2016). Beginning essentials in early childhood education . Boston, MA: Cengage Learning

[6] Gordon, A. M., & Browne, K. W. (2016). Beginning essentials in early childhood education . Boston, MA: Cengage Learning

[7] Gordon, A. M., & Browne, K. W. (2016). Beginning essentials in early childhood education . Boston, MA: Cengage Learning

[8] Image by COC OER Team is licensed under CC BY 4.0 .

[9] Oxford University Press. (2020). Theory. Oxford Dictionary. https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/theory

[10] Image by COC OER Team is licensed under CC BY 4.0 .

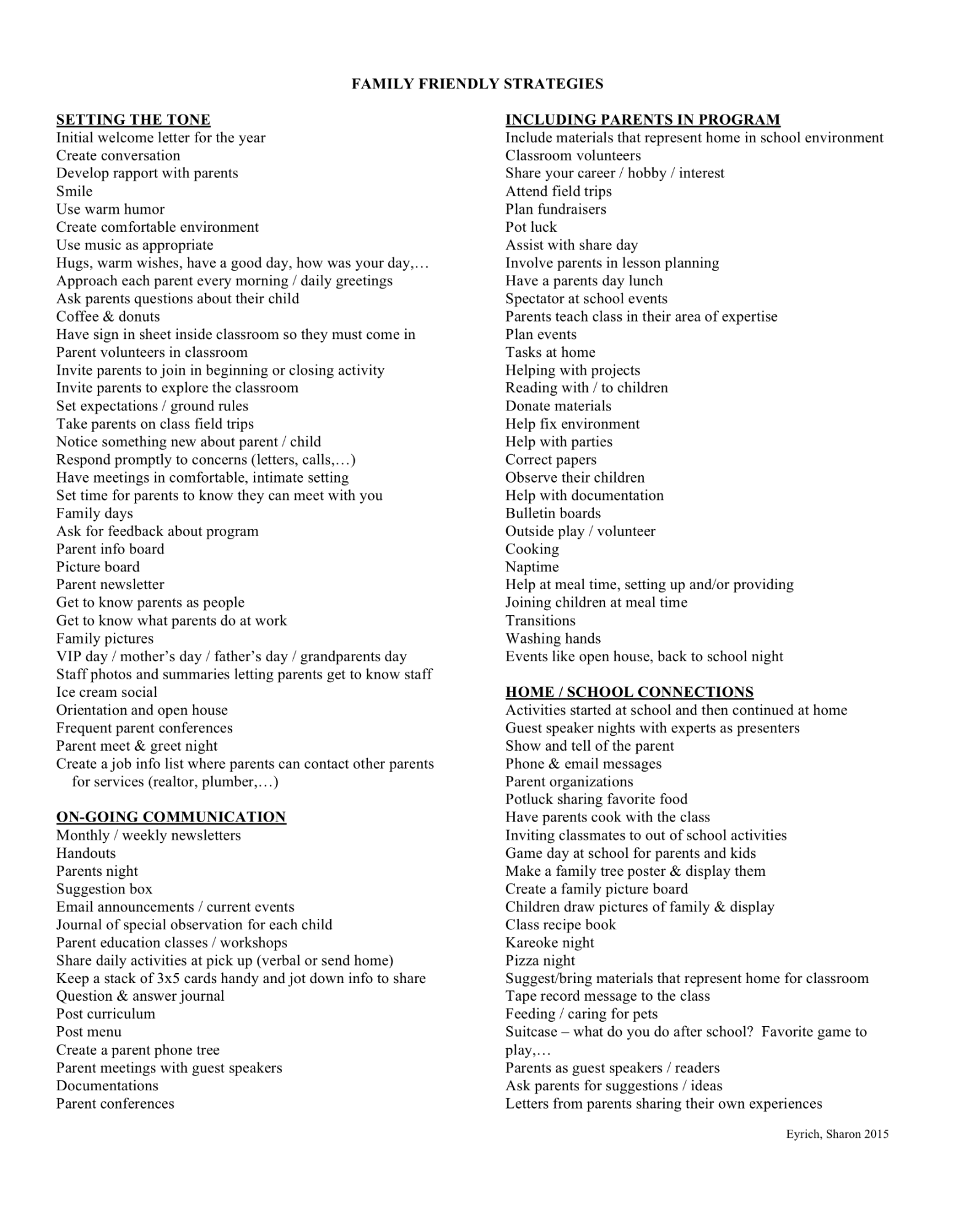

[11] Content by Sharon Eyrich (please do not alter)

[12] Content by Sharon Eyrich (please do not alter)

[13] Content by Sharon Eyrich (please do not alter)

[14] Gordon, A. M., & Browne, K. W. (2016). Beginning essentials in early childhood education . Boston, MA: Cengage Learning

[15] National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2009). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs serving children from birth through age 8. https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/position-statements/PSDAP.pdf

[16] Pam, N. (2013, April 7). Attachment. Psychology Dictionary . https://psychologydictionary.org/attachment/

[17] Reactive Attachment Disorder. (n.d). Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/reactive-attachment-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20352939

[18] Smith, P.K. (2013) Play . Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development. http://www.child-encyclopedia.com/play/according-experts

[19] Hughes, B. (2002). A Playworker’s Taxonomy of Play Types, 2 nd ed. London: PlayLink.

[20] Bongiorno, L. (n.d.). 10 thing every parent should know about play. National Association for the Education of Young Children. https://www.naeyc.org/our-work/families/10-things-every-parent-play

[21] Trauma Informed Care Project. (n.d). http://traumainformedcareproject.org

[22] Center for Disease Control (202-, April 3). Violence Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/aces/fastfact.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fviolenceprevention%2Fchildabuseandneglect%2Facestudy%2Faboutace.html

[23] Sinek, S. (2009, September 28). Start with why: How great leaders inspire action [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u4ZoJKF_VuA&feature=youtu.be

[24] National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2011, May). Code of ethical conduct and statement of commitment. Retrieved from https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/position-statements/Ethics%20Position%20Statement2011_09202013update.pdf .

[25] National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2009). Developmentally Appropriate Practice in Early Childhood Programs Serving Children from Birth through Age 8 . Retrieved from https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/position-statements/PSDAP.pdf

[26] Image by https://www.flickr.com/photos/usdagov/ is licensed under CC BY 2.0

[27] Image by Tatiana Syrikova from Pexel s

[28] Sharon Eyrich, 2019

[29] Lebedeva G. (2015, November/December) Building Brains One Relationship at a Time. Child Care Exchange. Retrieved from https://www.childcareexchange.com/article/building-brains-one-relationship-at-a-time/5022621/

[30] Tronick, E., & Beeghly, M. (2011). Infants’ meaning-making and the development of mental health problems. American Psychology , 66 (2), 107-119.

[31] College of the Canyon’s Early Childhood Education Practicum handbook

[32] College of the Canyon’s Early Childhood Education Practicum handbook

[33] Gladwell, M. (2002). The tipping point: How little things can make a big difference. Back Bay.

[34] Council for Professional Recognition. (2020) About the Child Development Associate (CDA) Credential. Retrieved from https://www.cdacouncil.org/about/cda-credential

[35] Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (n.d.) Early Childhood Credentials/Permits issued by the Commission. Retrieved from https://www.ctc.ca.gov/docs/default-source/educator-prep/early-care-files/ece-cred-types.pdf?sfvrsn=4f4fed04_0

[36] Gordon, A. M., & Browne, K. W. (2016). Beginning essentials in early childhood education . Boston, MA: Cengage Learning

[37] Gordon, A. M., & Browne, K. W. (2016). Beginning essentials in early childhood education . Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

[38] Image by COC OER Team is licensed under CC BY 4.0 .

[39] The Integrated Nature of Learning by the CDE is used with permission.

[40] Bentzen, W. R. (2009). Seeing young children: A guide to observing and recording behavior. (6 th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

[41] Bentzen, W. R. (2009). Seeing young children: A guide to observing and recording behavior. (6 th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

[42] Preschool Curriculum Framework, Volume 1 by the CDE is used with permission

[43] The Integrated Nature of Learning by the CDE is used with permission

[44] Gordon, A. M., & Browne, K. W. (2016). Beginning essentials in early childhood education . Boston, MA: Cengage Learning

[45] Gordon, A. M., & Browne, K. W. (2016). Beginning essentials in early childhood education . Boston, MA: Cengage Learning

[46] Rencken, K. S. (1996). Observation: The primary tool in assessment . Retrieved from https://www.childcareexchange.com/library/5011250.pdf

[47] Provided information and context throughout the chapter: Early Head Start National Resource Center at ZERO TO THREE. (2013) Observation: The heart of individualizing responsive care . Retrieved from https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/ default/files/pdf/ehs-ta-paper-15-observation.pdf

[48] Head Start (2020). Partnering with families [video transcript]. https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/video/transcripts/001219-partnering-with-families-highlights.pdf

[49] Image by VisionPic. net from Pexels

[50] Image by cottonbro from Pexels

[51] Image by Anna Shvets from Pexels

[52] Dress, A.R. (2020, May/June ). Supporting spiritual development in the early childhood classroom. https://www.ccie.com/article/supporting-spiritual-development-in-the-early-childhood-classroom/5025388/

[53] Image by Ian Joslin is licensed under CC BY 4.0 from "Introduction to Curriculum" by Kristin Beeve and Jennifer Paris, College of the Canyons is licensed under CC BY 4.0 / A derivative from the original work

[54] Image by Ian Joslin is licensed under CC BY 4.0 from "Introduction to Curriculum" by Kristin Beeve and Jennifer Paris, College of the Canyons is licensed under CC BY 4.0 / A derivative from the original work

[55] Image by Ian Joslin is licensed under CC BY 4.0 from "Introduction to Curriculum" by Kristin Beeve and Jennifer Paris, College of the Canyons is licensed under CC BY 4.0 / A derivative from the original work

[56] Image by Ian Joslin is licensed under CC BY 4.0 from "Introduction to Curriculum" by Kristin Beeve and Jennifer Paris, College of the Canyons is licensed under CC BY 4.0 / A derivative from the original work

[57] Image by Ian Joslin is licensed under CC BY 4.0 from "Introduction to Curriculum" by Kristin Beeve and Jennifer Paris, College of the Canyons is licensed under CC BY 4.0 / A derivative from the original work

[58] Image by Ian Joslin is licensed under CC BY 4.0 from "Introduction to Curriculum" by Kristin Beeve and Jennifer Paris, College of the Canyons is licensed under CC BY 4.0 / A derivative from the original work

[59] Image by Ian Joslin is licensed under CC BY 4.0 from "Introduction to Curriculum" by Kristin Beeve and Jennifer Paris, College of the Canyons is licensed under CC BY 4.0 / A derivative from the original work

[60] Image by Ian Joslin is licensed under CC BY 4.0 from "Introduction to Curriculum" by Kristin Beeve and Jennifer Paris, College of the Canyons is licensed under CC BY 4.0 / A derivative from the original work

[61] Image by Ian Joslin is licensed under CC BY 4.0 from "Introduction to Curriculum" by Kristin Beeve and Jennifer Paris, College of the Canyons is licensed under CC BY 4.0 / A derivative from the original work

[62] Image by Ian Joslin is licensed under CC BY 4.0 from "Introduction to Curriculum" by Kristin Beeve and Jennifer Paris, College of the Canyons is licensed under CC BY 4.0 / A derivative from the original work

[63] Image by Ian Joslin is licensed under CC BY 4.0 from "Introduction to Curriculum" by Kristin Beeve and Jennifer Paris, College of the Canyons is licensed under CC BY 4.0 / A derivative from the original work

[64] Image by Ian Joslin is licensed under CC BY 4.0 from "Introduction to Curriculum" by Kristin Beeve and Jennifer Paris, College of the Canyons is licensed under CC BY 4.0 / A derivative from the original work

[65] Image by Ian Joslin is licensed under CC BY 4.0 from "Introduction to Curriculum" by Kristin Beeve and Jennifer Paris, College of the Canyons is licensed under CC BY 4.0 / A derivative from the original work

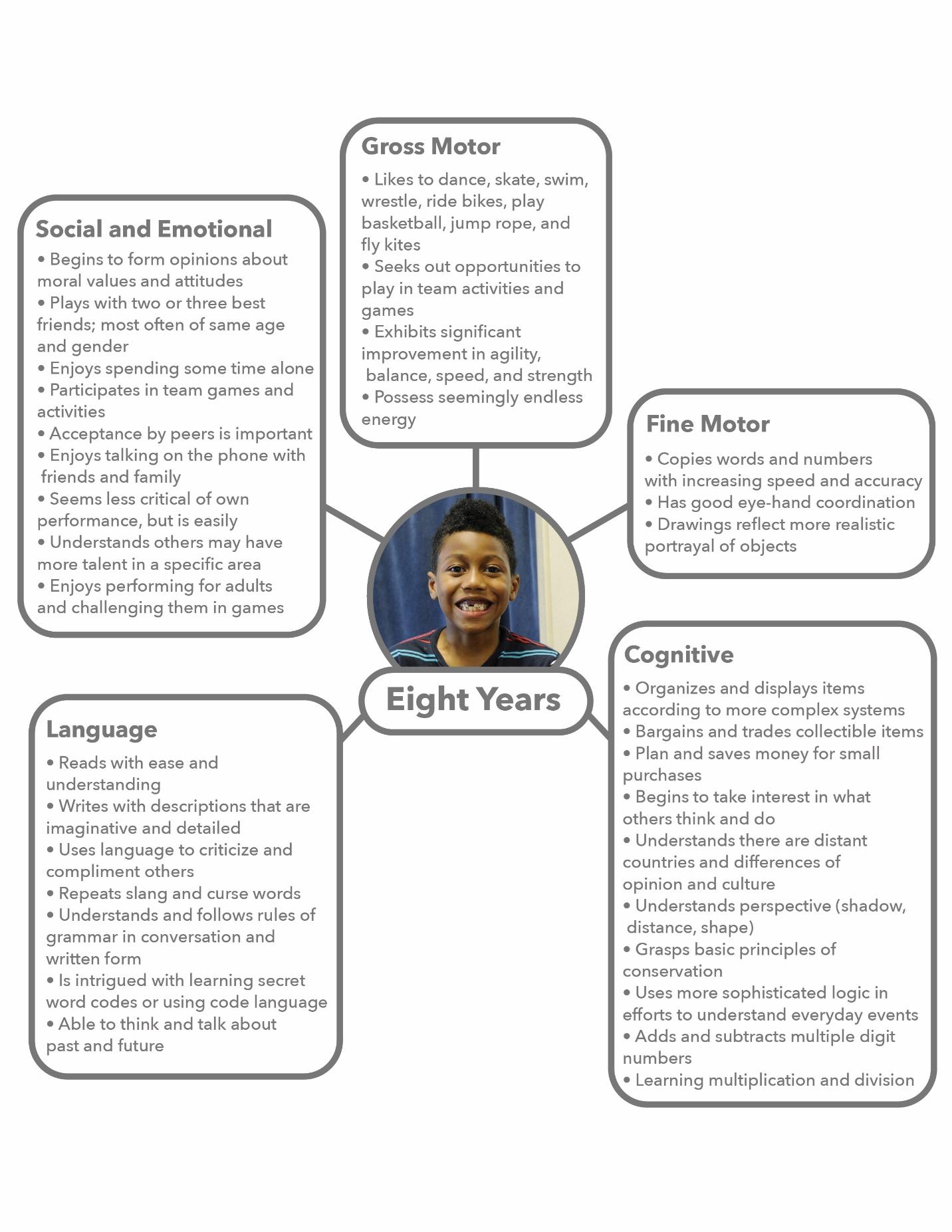

[66] Factors influencing Behavior by Age by Wendy Ruiz is licensed under CC BY 4.0

[67] National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2009). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs serving children from birth through age 8. https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/position-statements/PSDAP.pdf

[68] Content by Kristin Beeve is licensed under CC BY 4.0

[69] Image by Ian Joslin is licensed by CC-BY-4.0 from "Introduction to Curriculum" by Kristin Beeve and Jennifer Paris, College of the Canyons is licensed under CC BY 4.0 / A derivative from the original work

[70] Sharon Eyrich, 2020

[71] Play by Skitterphoto is licensed under CC0

[72] Hughes, B. (2002) A playworker’s taxonomy of play types (2 nd ed.). PlayLink.

[73] Parten, M. B. (1932). Social participation among preschool children. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 27 (3). 243–269. doi:10.1037/h0074524

[74] Sharon Eyrich, 2016

[75] Image by the California Department of Education is used with permission

[76] Image by Olenda Pea Perez is in the public domain

[77] Sharon Eyrich, 2015

[78] Gordon, A. M., & Browne, K. W. (2016). Beginning essentials in early childhood education . Boston, MA: Cengage Learning

[79] Gordon, A. M., & Browne, K. W. (2016). Beginning essentials in early childhood education . Boston, MA: Cengage Learning

[80] Gordon, A. M., & Browne, K. W. (2016). Beginning essentials in early childhood education . Boston, MA: Cengage Learning

[81] Biermeier, M. A. (2015). Inspired by Reggio Emilia: Emergent curriculum in relationship-driven learning environments. Young Children (70) 5. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/pubs/yc/nov2015/emergent-curriculum

[82] Preschool Program Guidelines by the California Department of Education is used with permission

[83] Gordon, A. M., & Browne, K. W. (2016). Beginning essentials in early childhood education . Cengage.

[84] Dodge, D. T., Coker, L. J., & Heroman, K. (2002). The Creative Curriculum for Preschoolers (4 th ed.). Teaching Strategies.

[85] Preschool Program Guidelines by the California Department of Education is used with permission

[86] Photo by Karolina Grabowska from Pexels

[87] Cropped from Photo by Karolina Grabowska from Pexels

[88] Child Care Center General Licensing Requirements is in the public domain

[89] Image by Community Playthings is used with permission

[90] Image by Community Playthings is used with permission

[91] Image by Community Playthings is used with permission

[92] MiraCosta College (n.d.). Preschool Environment Checklist. Retrieved from https://www.miracosta.edu/instruction/childdevelopmentcenter/downloads/5.2PreschoolEnvironmentChecklist.pdf

[93] Heaving decorated classrooms disrupt attention and learning in young children. (2014, May 27). https://www.psychologicalscience.org/news/releases/heavily-decorated-classrooms-disrupt-attention-and-learning-in-young-children.html

[94] Social and Emotional Development is in the public domain

[95] Image by Orione Conceição from Pexels

[96] Gordon, A. M., & Browne, K. W. (2016). Beginning essentials in early childhood education . Cengage.

[97] Gillespie, L. (n.d.). It takes two: The role of co-regulation in building self-regulation skills. https://www.zerotothree.org/resources/1777-it-takes-two-the-role-of-co-regulation-in-building-self-regulation-skills

[98] Image by Nicholas Githiri from Pexels

[99] Perry, B. D. (n.d.). Creating an emotionally safe classroom. https://www.scholastic.com/teachers/articles/teaching-content/creating-emotionally-safe-classroom/

[100] Responsive Caregiving as an Effective Practice to Support Children's Social and Emotional Development is in the public domain

[101] Perry, B. D. (n.d.). Creating an emotionally safe classroom. https://www.scholastic.com/teachers/articles/teaching-content/creating-emotionally-safe-classroom/

[102] Preschool Program Guidelines by the California Department of Education is used with permission

[103] Image from the Center on the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning is used with permission

[104] Gordon, A. M., & Browne, K. W. (2016). Beginning essentials in early childhood education . Cengage.

[105] Image from PowerPoint is in public domain

[106] Image from PowerPoint is in public domain

[107] Draft Policy Statement on Inclusion of Children with Disabilities Executive Summary is in the public domain

[108] FPG Child Development Institute. (n.d.). Environment Rating Scales ®. https://ers.fpg.unc.edu/

[109] Dodge, D. T., Coker, L. J., & Heroman, K. (2002). The Creative Curriculum for Preschoolers (4 th ed.). Teaching Strategies.

[110] Mayntz, M. (n.d.). Definitions of Family. https://family.lovetoknow.com/definition-family

[111] NAEYC. (2011). NAEYC Code of ethical conduct and statement of commitment. https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/position-statements/Ethics%20Position%20Statement2011_09202013update.pdf

[112] Six images in top two rows are used by permission from Family Partnerships and Culture

Bottom left image by Surrogacy-UK is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Bottom center image by Tinker Air Force Base is public domain

Bottom right image by Maggie Zhao is free to be used and modified

[113] Milbrand, L. (2019, July). How 4 different parenting styles can affect your kids. https://www.thebump.com/a/parenting-styles

[114] The Six Stages of Parenthood. (n.d.) http://arbetterbeginnings.com/sites/default/files/pdf_files/Six%20Stages%20of%20Parenthood.pdf

[115] Sharon Eyrich, 2015

[116] NAEYC. (2011). NAEYC Code of ethical conduct and statement of commitment. https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/position-statements/Ethics%20Position%20Statement2011_09202013update.pdf

[117] NAEYC. (2011). NAEYC Code of ethical conduct and statement of commitment. https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/position-statements/Ethics%20Position%20Statement2011_09202013update.pdf

[118] https://www.naeyc.org/resources/topics/dap/5-guidelines-effective-teaching

[119] Image by the California Department of Education is used with permission

[120] Gordon, A. M., & Browne, K. W. (2016). Beginning essentials in early childhood education . Cengage.

[121] Seplocha, H. (n.d.). Partnerships for learning: Conferencing with families . https://dphhs.mt.gov/Portals/85/hcsd/documents/ChildCare/STARS/Kits/3to4NAEYCconferencing.pdf

[122] Image used by permission from The Infant/Toddler Learning and Development Program Guidelines,

Second Edition

[123] Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (2017). Parent engagement practices improve outcomes for preschool children. https://www.peopleservingpeople.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Parent_Engagement__Preschool_Outcomes.pdf