Clearing the Market at Equilibrium Price and Quantity

When a market achieves perfect equilibrium there is no excess supply or demand, which theoretically results in a market clearing.

Learning objectives

Define market equilibrium

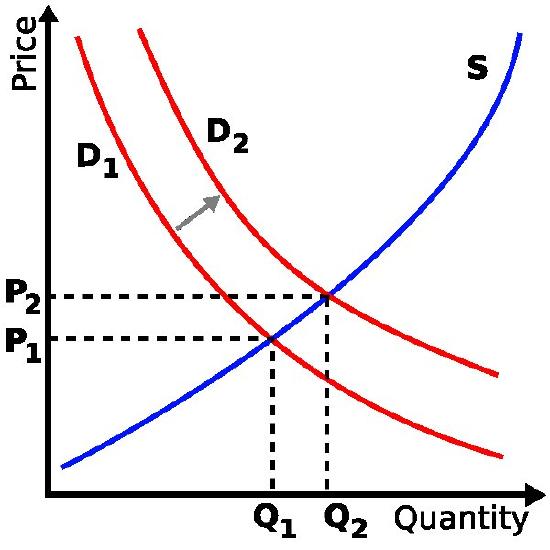

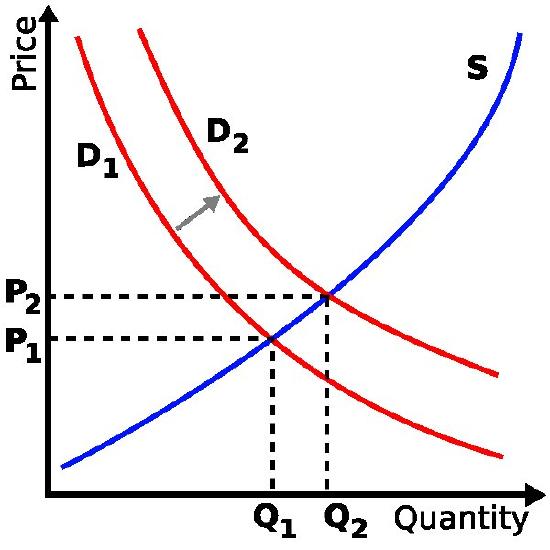

The interdependent relationship between supply and demand in the field of economics is inherently designed to identify the ideal price and quantity of a given product or service in a marketplace. This equilibrium point is represented by the intersection of a downward sloping demand line and an upward sloping supply line, with price as the y-axis and quantity as the x-axis. At perfect equilibrium there is no excess demand (represented by ‘A’ in the figure) or excess supply (represented by ‘B’ in the figure), which theoretically results in a market clearing.

Equilibrium Pricing: This chart effectively highlights the various basic implications of a simple supply and demand chart. The equilibrium point is where market clearing will theoretically occur.

Market Clearing Assumptions

A market clearing, by definition, is the economic assumption that the quantity supplied will consistently align with the quantity demanded. This definition requires a variety of assumptions which simplify the complexities of real markets to coincide with a more theoretical framework, most centrally the assumptions of perfect competition and Say’s Law:

- Perfect competition is a market where the price determined for a given good or service is not affected by external forces or competition in a way that allows incumbents (companies) to attain market influence.

- Say’s Law hinges on the concept that capital loses value over time, or that money is essentially perishable. The simplest way to view this law is interest rates. When you invest or owe money, that capital accrues interest due to the fact that there is an opportunity cost in not investing that money elsewhere. This opportunity cost creates the assumption that money will not go unused.

Combining these two assumptions, in a perfectly competitive market the amount of a product or service that is supplied at a given price will equate to the amount demanded, clearing the market of all goods/services at a given equilibrium point.

Theory and Practice

While this concept of market clearing resonates well in theory, the actual execution of markets is very rarely perfect. Markets demonstrate consistent shifts of supply and shifts of demand based on a wide spectrum of externalities. Even in static markets there is competitive consolidation that allows companies to charge differing price points than that of the equilibrium. The concept of monopolies provides a good example for this experience, as monopolies (see example) can control price and quantity simultaneously.

Another classic criticism of market clearing is the way in which the labor market functions. In the 1930’s, during the worst depression recorded in the United States, the labor market did not clear the way economic theories of market clearing would assume it would. Instead, there seemed to be what John Maynard-Keynes (father of Keynesian Economics) called ‘stickiness,’ which preventing the market from normalizing. The importance of raising these concerns is the understanding that while the concept of market clearing, equilibrium and supply/demand charts are highly useful in understanding the basic functioning of markets, reality does not always conform with these models.

Impacts of Surpluses and Shortages on Market Equilibrium

The existence of surpluses or shortages in supply will result in disequilibrium, or a lack of balance between supply and demand levels.

Learning objectives

Infer the outcomes of departures from equilibrium using the model of supply and demand

In the analysis of market equilibrium, specifically for pricing and volume determinations, a thorough understanding of the supply and demand inputs is critical to economics. Surpluses and shortages on the supply end can have substantial impacts on both the pricing of a specific product or service, alongside the overall quantity sold over time. Shifts such as these in the supply availability results in disequilibrium, or essentially a lack of balance between current supply and demand levels. Surpluses and shortages often result in market inefficiencies due to a shifting market equilibrium.

Surpluses

Surpluses, or excess supply, indicate that the quantity of a good or service exceeds the demand for that particular good at the price in which the producers would wish to sell (equilibrium level). This inefficiency is heavily correlated in circumstances where the price of a good is set too high, resulting in a diminished demand while the quantity available gains excess. There are substantial business risks inherently built into the concept of surpluses, as the general outcome will be either selling off inventory at sub-par prices or leftover unsold inventory. In both scenarios businesses will be forced to minimize margins or incorporate losses on that particular good. Governmental intervention can often create surplus as well, particularly through the utilization of a price floor if it is set at a price above the market equilibrium.

Price Floor: A price floor ensures a minimum price is charged for a specific good, often higher than that what the previous market equilibrium determined. This can result in a surplus.

In a perfectly competitive market, particularly pertaining to goods that are not perishable, excess supply is equivalent to the quantity available in the market beyond the equilibrium point of intersection between supply and demand. In this theoretical scenario the equilibrium point will transition towards a lower price point due to the increased supply, which will in turn motivate consumers to purchase a higher quantity as a result. This allows the economic model of the market to correct itself.

Shortages

Inversely, shortage is a term used to indicate that the supply produced is below that of the quantity being demanded by the consumers. This disparity implies that the current market equilibrium at a given price is unfit for the current supply and demand relationship, noting that the price is set too low. It could also indicate that the desired good has a low level of affordability by the general public, and can be a dangerous societal risk for necessary commodities. Indeed, Garrett Hardin emphasized that a shortage of supply could also be perceived as a ‘longage’ of demand, as the two are inversely related. From this vantage point shortages can be attributed to population growth as much as resource scarcity.

In a perfectly competitive market, a shortage in supply will ultimately result in a shift in the equilibrium point, transitioning towards a higher price point due to the limited supply availability. This will prioritize who receives the good or service based upon their willingness and ability to pay a premium for the specific item in demand, leveraging those along the demand curve who are at higher levels with higher ability and willingness to pay.

Changes in Demand and Supply and Impacts on Equilibrium

Alterations to overall supply or demand dictate the cross-section or equilibrium, ascertaining price and volume for a product or service.

Learning objectives

Illustrate how changes in supply or demand impact the market equilibrium

The interdependent relationship between the supply of a given product or service and the overall demand exercised by interested parties generates a theoretical equilibrium point, dictating the average market price and purchased volume relative to that price. In a static market it would be reasonable to assume that prices and volumes would remain fairly predictable and consistent relative to the population, but realistic markets are not static. Instead, markets are in constant flux as demands and supplies are subjected to varying driving forces and influences. These shifts play a critical role in altering market equilibrium price points and volumes for products and services, requiring constant vigilance and adaptation by providers and consumers. To better understand market variations, it is useful to examine how changes in supply and demand may occur, as well as the impacts and implications of these changes.

Demand Shifts

Demand shifts are defined by more or less of a given product or service being required at a fixed price, resulting in a shift of both price and quantity. As would be assumed, an increase in demand will shift price upwards and volume to the right, increasing the overall value of both metrics relative to the prior equilibrium point. Alternately, a decrease in demand will shift price downwards and volume to the left, decreasing both measurements to realign equilibrium with a reduced demand.

Demand Shifts: In this graph, the demand curve (red) has been affected by an increase in demand. This consequently increases price at a given volume.

Demand shifts can be caused by a wide variety of factors, but largely revolve around drivers of consumer behavior and circumstances. Demand shifts can therefore often be affected by economic factors such as average spending power per person in a given economy or overall average income. Demand can also be affected by cultural changes, demographic shifts, availability of substitutes, environmental factors and concerns (e.g. climate change), politics, and advances in science (e.g. declining demand for unhealthy foods). Demand is particularly malleable in respect to goods that are not necessities, thus are desired or not based upon sociological norms.

Supply Shifts

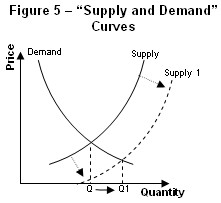

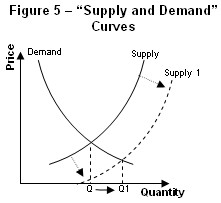

Supply shifts are defined by more or less of a particular product/service being available to fulfill a given demand, affecting the equilibrium point by shifting the supply curve upwards or downwards. A supply shift to the right, indicating more availability of the specified product or service, will create a lower price point and a higher volume assuming a fixed demand. Alternately, a decrease in supply with a consistent given demand will see an increase in price and a decrease in quantity. This is an intuitive theory underlining the fact that scarcity is relevant to the willingness to pay.

Supply Shifts: In this supply and demand chart we see an increase in the supply provided, shifting quantity to the right and price down. More of a given product, assuming the same demand, will result in lower price points at the equilibrium.

Supply shifts, similar to demand shifts, can ultimately be a result of a wide variety of external factors. As discussed above, scarcity plays a critical role in pricing and thus controlling supply is often even considered a strategic play by companies in specific industries (most notably industries like precious stones, rare earth metals, etc.). Supply shifts can also be a result of technological advances, over-utilization or consumption, globalization, supply-chain efficiency, and economics. For example, the discovery of a new gold deposit, acts as a shock to the supply of gold, shifting the curve right.

Equilibrium

In combining these two potential shifts, equilibrium is constantly subjected to both factors resulting in supply shifts and factors resulting in demand shifts. Due to the demand curve sloping downward and the supply curve sloping upwards, they inadvertently will cross at some given point on any supply/demand chart. This cross-section, or equilibrium, serves as a price and quantity tracking point based upon the consistent inputs of overall demand and supply availability. Any change in either factor will result in immediate impact on equilibrium, balancing the new demand or supply with a corresponding volume and appropriate average price point.