1.16: Backlash against Globalization 3.0

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 226217

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)A backlash against globalization has been on the rise in recent decades. Globalization refers to the increase in collaboration between nations, companies, and economies because of the transnational trade of goods and services. It denotes the interdependence of various systems on an international level (Lang, 2006). The anti-globalization movement roughly refers to the broad sentiments associated with an apparent decrease in support among the public and with policy decisions. Globalization has had a wide-ranging impact on global economics, culture, and politics. Backlash can be seen in every individual category, with general overlap between topics (Walter, 2021). Thus, those who oppose political globalization do not necessarily oppose social or economic globalization. However, some qualms go hand in hand. For example, opposing the European Courts of Human Rights, as many do, is a mixture of political and cultural anti-globalization sentiments (Walter, 2021). There are three eras of globalization worth noting that provide context for globalization and backlash against such integration.

Our current era is a new era of globalization that took off around the late 1980s as the Soviet Union fell, and almost all countries were choosing to adopt some level of democracy. Most importantly, during this time, an overwhelming majority of countries chose to open their markets and adopt capitalism. This was the introduction of globalization 3.0. In his 2007 essay, The World is Flat, American political commentator and author Thomas L. Friedman divides the history of globalization into three eras. Each era refers to a period in time that was defined by very high economic growth along with increased collaboration and integration in the global economy of the time. These eras particularly occurred under periods with a recognizable hegemonic power which resulted in stable trade. However, international economic integration waxes and wanes and there was often protectionist sentiment that would be a regular pattern in all three eras.

Globalization 1.0, or Pax Mongolica, is defined by the Mongol Empire in the early 13th century (as well as the Yuan Dynasty) which usurped unprecedented territory, but especially important- their hegemonic power resulted in a stable overland trade route from Europe to China, even spreading economic integration to the Horn of Africa. Globalization 2.0, known as Pax Britannica, involved European expansion in the 19th to early 20th century, where there was rapid economic growth with the rise of the Industrial Revolution. During this period, there was stability under the hegemon of the British Empire.

Globalization 2.0 ended around the interwar period from 1918-1938, the same time that the British Empire’s place as the global hegemon fell and the United States’ position as a global hegemon arose. The continued pattern is that when there is a hegemon there to bring stability, it promotes trade, collaboration, and growth in economic activity. There are always winners and losers in the global economy and the various factors involved may lead to a backlash by those who feel threatened by certain patterns of integration.

The final and most recent era is Globalization 3.0. This is our current era and is defined by newfound possibilities for global collaboration but also increased competition. In this era we are witnessing, as seen in past eras, unprecedented levels of integration with rapid increases in the ability to trade in terms of scale and speed, especially through advanced tools such as the introduction of the internet in the 21st century. It is also coinciding with a power shift away from the West and increasingly towards Asia. This era has sparked great controversy over the politicization of topics that are otherwise apolitical in nature (Lang, 2006). Economic globalization has faced backlash in the form of protests against the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and other international financial institutions, while others worry about lasting effects on national sovereignty because of political globalization. These are just a handful of the various antiglobalization sentiments shared by many. The backlash is not a new concept- it has been building for decades. Researchers suggest spikes in opposition occur when mass public groups incur losses, whether that be the election of former president Donald J. Trump or other developments such as youth-led movements for climate action (Walter, 2021).

The rise in skepticism in globalization 3.0 has had a direct correlation to a rise in protectionism, isolationism, and nationalism-related policies. Some of these policies are inherently harmful to and threaten the current means of international order. These theories and policies will be defined and analyzed throughout the following sections.

Globalization

Historical Background

Opposition towards globalization has been increasing. Scholars believe the concept was introduced in the early 18th century as various world powers, cultures, and economies became more and more integrated. Others attribute the dawn of globalization to Christopher Columbus’ journey to the New World, leading to the Columbian Exchange, during which European influence traveled across oceans to the Americas and vice versa. Regardless of one’s interpretation of the commencement of the concept, globalization made it so that past borders were no longer a limit to trade. Author Anthony Giddens defined globalization as “the stretching of social connections between the local and the distant” (Giddens, 2013), highlighting the cooperation of distant nations. From the globalization of trade to that of production and finance, the collaboration of nations has been subject to opposition for quite some time.

The “post–Cold War” world ushered in an unprecedented wave of geopolitical change. Following the fall of the Soviet Union, the United States quickly positioned itself at the top of the “food chain,” the unparalleled “hyperpower.” In Globalization 3.0 we are witnessing a power shift from the West to other rising states, such as China and India, whose economies may continue to overpower that of the West. Evidently, the shifting of power and influence has prompted heated debate, many of which have sparked new policies based on economic theories rooted in anti-globalization sentiments.

The Economics of Globalization

Discussing the backlash against globalization naturally leads to a discussion of the economic dimensions that make it up. The second liberal international order that rose after World War II can today be found in at least two forms. The first is referred to by some as hyper globalization and includes policies on rules within countries that promote capitalist markets, the movement of capital between countries, free trade between countries, and the equal treatment of foreign direct investment. The second is known as embedded liberalism, which, like the first form, promotes the free movement of goods and services between countries and understands that this can cause disruptions to societies. Therefore, it includes the sheltering of the most vulnerable parts of society while also compensating those who are negatively affected by an open economy (Lake et al., 2021). However, the push towards economic liberalism has resulted in conflicts with those who prefer policies closer to the Westphalian order. This refers to a system of international relations that emerged in Europe after the Thirty Years’ War in the mid-17th century, prompted by the signing of the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648. This system was characterized by the principle of state sovereignty, which established clearly that each state had exclusive control over its territory, government, and domestic affairs. The Westphalian order also established the idea of non-interference in the internal affairs of other states, the recognition of borders, the concept of territorial integrity, and the principle of equal legal standing between states. The problem arises as those with neoliberal ideals push for the acceptance of liberal economic domestic policies as a normative idea (Lake et al., 2021). The following sections will explore economic theories which support globalization and theories which attempt to explain backlash against globalization.

The Benefits of Globalization

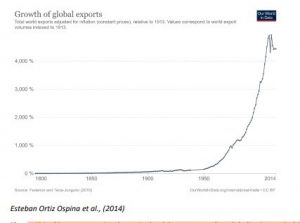

In an ever-changing world, where the height of our technology has allowed societies to network with others through improved communication and transportation, international trade has been rapidly increasing since the 1900s (Esteban Ortiz Ospina et al., 2014). Proponents of globalization look to the impact it has had on the increased access to goods that societies have been able to trade and the reduced prices that come with it as both local and foreign producers compete against each other to sell their goods to the public (Joyce S. Osland, 2003). The “vent for surplus” theory was first founded by Adam Smith and later critiqued by Hla Myint, who is a Burmese economist known for his contributions to welfare economics, highlighting the importance of export orientation as an effective growth tool. He suggested that, because businesses and nations have the capability to produce more than what their local public can consume, these businesses and nations will look to the international market as another source of consumption for their excess goods (Victor S. Venida, 2000). The capacity to produce more and the extra source of consumption by the “vent for surplus theory” not only explains why the trend of globalization has increased, but it also explains how consumers would support globalization as they have access to cheaper goods and see that their economy is growing.

‘Competition’ is a major theme in the debate surrounding globalization and later in this chapter, you will learn about how it is the fear of losing competitiveness that leads some to pursue protectionist policies or back out of international trade altogether. Still, supporters also cite competition as a contributing factor to how it leads to nations experiencing socio-economic rewards that they would not have gained had they not globalized. Due to the competition between developed and developing nations, supporters have cited that competition has led to developing countries enhancing the quality and specialization of their workforce in hopes to better compete with their counterparts (Joyce S. Osland, 2003).

However, despite the number of arguments researchers and academics will cite in support of globalization, there is still a wide range of literature that argues against globalization, highlighting the negative consequences that certain parts of the world are facing because of it. Now that you understand on a basic level some of the benefits of globalization, such as the increased incentive to specialize and improve technical skills for developing states, greater access to cheaper goods for consumers, as well as a larger market for producers to sell those goods. We will next explore the backlash against globalization.

Backlash Against Globalization

Non-material Issues

Globalization has brought about many non-material issues that have impacted societies. One of the main issues is the erosion of cultural diversity, as globalizing forces, such as the spread of Western media, and consumerism, have led to the homogenization of cultures, particularly among younger generations (Croteau & Hoynes, 2013). These aspects have led to the loss of traditional knowledge, practices, and beliefs as well as the marginalization of minority cultures. Additionally, globalization has led to the concentration of power and wealth in the hands of a few global corporations and countries, exacerbating social inequality and poverty (Ferri, 2003). At the same time, the majority of the world’s population has not seen significant improvements in their standards of living. This has led to growing social and economic disparities within and between countries, contributing to political unrest, migration, and other social challenges. Finally, globalization has also contributed to environmental degradation, as increased economic activity has led to greater exploitation of natural resources and increased pollution.

This new economic activity has three major contributing factors: increased ability to transport more goods faster, economic specialization, and biodiversity loss brought about by globalization (Stobierski, 2021). Economic specialization is the process by which an organization concentrates its labor and resources on the production of a particular resource to create a comparative advantage for the economy. This hyper-focus or concentration has led to the overconsumption and extraction of natural resources to the detriment of some local communities and the environment, resulting in overfishing, increased pollution, extreme deforestation, and other environmental issues arising from trying to meet a competitive advantage in the global market. At the same time, decreased biodiversity is brought about by the loss of habitats and overhunting brought about by economic specialization and consumer demands. Another factor decreasing biodiversity is the introduction of invasive foreign plants and animals worldwide due to global shipping networks. That being said, states and the public are becoming increasingly aware of these non-material issues and have started to take action to minimize the negative non-material issues brought about by globalization. We will next explore the backlash against globalization using current economic theories and politics.

Theories on Backlash Against Globalization

There are three anti-globalization theories that are built upon classical trade theories to relate globalization to income inequality: These are a neo or enriched version of the Heckscher-Ohlin and Stolper-Samuelson model (neo-HOSS), new new trade theory (NNTT), and the theory of economic geography.

Originally introduced by Haskel et al. (2012), neo-HOSS theory adds to the HOSS model the idea that workers are heterogenous, each with various levels of skill. The implication of doing so is that a drop in the relative price of a labor-intensive good by some force reduces the wage of lower-skilled labor, but also that the gains from the force which pushes prices down are distributed to only a small portion of higher-skilled labor. It is important to note that this force could be either globalization or technological advances, but finds that the more that globalization is shown to be linked to a decrease in prices, the greater the backlash to globalization will be (Flaherty et al., 2021).

New new trade theory, on the other hand, focuses on a firm level to explain the effect of globalization-induced wage inequality. NNTT reasons that, due to the high associated costs of imports and exports, only the largest firms will be able to enter this market, and that the gains from trade will make them even larger. Subsequently, domestic markets will be overtaken by the largest global firms, driving down profits for domestic firms and completely driving out local establishments. Adding the previously discussed idea of heterogeneous workers into the theory, profits are concentrated for workers at the top firms, and workers in smaller domestic firms are left out, as demonstrated by Helpman et al. (2010) and Akerman et al. (2013).

Looking at an even broader scale, economic geography “explores the origins and effects of one of a society’s most readily observable features: the unequal distribution of economic activity across space” (Flaherty et al., 2021). This theory, also called new economic geography, originates from trade economics, mainly by Krugman (1991), Krugman et al. (1995), and Ottaviano et al. (1998). Findings from Broz et al. (2021), as discussed earlier, show how globalization’s effects are felt most significantly at a community level. Flaherty et al. (2021) complement their findings by demonstrating how globalization leads to economic stagnation and decline on a regional level, leaving only a handful of cities to benefit. The causal mechanism behind this theory is that globalization lowers trade costs, allowing firms to gain more from locating themselves in areas with the most benefits. Such areas become large cities because they have advantages like access to ports or natural resources, access to key infrastructure, a large and specialized labor pool, and a diverse consumer base. As firms can locate in these large cities because of lowering trade costs from globalization, the areas continue to grow in a process known as agglomeration. However, this growth is at the cost of less advantageous cities. The result is large inequality between regions and within the largest cities (Breinlich et al., 2014).

Again, these theories are constrained in that they do not discuss the non-economic mechanisms through which inequality arises and only offer purely material reasons for the backlash against globalization. Data from Jones (2018) suggests that over half of Americans view trade favorably, despite the literature that inequality has been growing. This is indicative of factors other than just economics impacting attitudes toward globalization. In addition, neo-HOSS, NNTT, and the economic geography theory are most applicable to high-income countries. Further research will need to test their robustness when applied to lower-income countries. Next, we will analyze political ideologies that further our understanding of backlash to globalization.

Backlash Against Globalization: Nationalist Populism

Nationalism and populism are two theories that are often combined when discussing international relations. Nationalism is the political ideology that sovereignty interests and identity takes precedence over other states, while populism is the political strategy of appealing to the people of a state rather than the elites. The difference between them for this discussion is the economic solutions they propose to solve the issues brought on by globalization. Right-wing populism proposes protectionism, whereas left-wing populism proposes redistribution, an idea that is also supported by embedded liberalism. Nationalist populism, therefore, describes the meeting of these two like theories on an international level without specifying their specific economic leaning (Singh, 2021). Although nationalist populist values differ across regions, left-wing populism shares in its rejection of surrendering economic sovereignty to an international organization. Specific values include hostility towards international trade, investment, and finance, and in the case of European nationalist populists, there is also hostility towards European integration (Eichengreen, 2020). Although nationalist populism was not founded as a counter to globalization, its growing presence in areas that have been negatively affected by globalization indicates its role in weakening the liberal economic order. Broz et al. (2021) find that the distributional effects of globalization, a steady decline in manufacturing, pressure from countries like China on lower-skill and education workers, and the financial crisis of 2008 were major factors in the explosive growth of nationalist populism in the OECD. In addition, the distributional effects of globalization were felt most significantly at the community level, especially those with middle-class incomes and industrial communities.

However, focusing on the economic side of nationalist populist theory results in a purely material explanation for the rise in the backlash against globalization and ignores the debate over whether the driving force against globalization is material or nonmaterial in nature. There are other findings that align with that of Broz et al. (2019) where the losers of globalization, those who are more exposed to its risks, and individuals with lower skills are more likely to support anti-globalization policies and parties (Walter, 2021). At the same time, other findings such as Rommel et al. (2018) do not align with the idea that those more affected by the negatives of globalization are more likely to vote for anti-globalization measures.

The Politics of Anti-globalization

As alluded to in the economic theories behind the backlash to globalization, a contention of importance and issue is in the political arena, with regard to cultural backlash or the ability to respond to those risks.

The impact globalization has on people helps reveal the backlash against globalization and why. Nationalism, populism, and social grievances play a key role in a general population and reaction to policy or globalization. A key issue is alienation, where people feel alone and separated from issues. This has been brought up in many different works of literature from classical liberalism to Marxist ideas. Failing to address this key part also affects backlash. The current backlash against globalization is a complex issue, stemming from a reaction to the failure of traditional parties not adequately responding to pressing issues. The deindustrialization of regions, combined with feelings of neglect and being on the losing end of policies, has helped make domestic (American) sentiment against globalization (Broz, Frieden, Weymouth, 2021). Multiple crises in the last two decades, such as the Great Recession, the coronavirus pandemic, inflation, oil shocks, the rising cost of living, and many more regional conflicts, have built a lengthy line of grievances and gripes people have over globalization.

In America, people who have been on the losing end of these policies and feeling alienated from governance have as a result found economic populism to be popular. In other parts of the globe, the backlash extends into responses due to being on the losing end of trade deals or suffering external factors that are not expected. For example, places that historically suffered from colonization and imperialism are much more cynical about the benefits of globalization. We also must look at how areas manage debt, as well as how it factors into the economic response. This all factors into an enormous chain of events that can affect the ability of the state or region to respond to a crisis, and by extension, motivate backlash to globalization. In an upcoming case study, we will see some of these factors in action.

Case Studies

Case Study: Backlash in Puerto Rico

An example of how these factors come into play is the current economic crisis and response in the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico. This territory had over $72 billion in debt in 2016, was defaulting on the debt, and was already in austerity with its budget (Espada, 2021). In 2015, poverty levels were at 46%, and the island was in an economic depression since 2006 (Caraballo-Cueto, 2021). The island has suffered a mass exodus, as people are fleeing the island because of poverty and lack of opportunities. This resulted in the creation of a fiscal board, PROMESA, by the U.S. federal government in 2016 (Espada, 2021). This board has received little praise from the people residing on the island, as austerity and tax exemptions for businesses were the policies perceived by them (Espada, 2021).

Part of this policy distrust goes back to the 50s and 60s when,during an industrialization plan initiated by the American federal government, there was hard growth at the cost of families and culture of the island, and forced migrations (Caraballo-Cueto. 2021) (Fuentes-Ramirez, Hosteler-Diaz, 2020). In Ricardo R. Fuentes-Ramirez’s analysis, The Political Economy of Puerto Rico: Surplus Use and Class Structure, “between 1950 and 1972 annual growth rates were on average 6.1 percent, but more than half of the population remained in poverty and unemployment never fell below 10 percent” (Fuentes-Ramirez, Hosteler-Diaz, 2020). For this economic success and opening of markets, Puerto Rico required a constant valve of migrations to the mainland to help reduce poverty and get population control. This resulted in the splitting of families as men would leave for the mainland due to patriarchal cultural norms, leaving wives and loved ones to take over the home. This fractured cultural norms in the society (Caraballo-Cueto. 2021) (Fuentes-Ramirez, Hosteler-Diaz, 2020).

This caused massive stratification in Puerto Rican society, as the losers of the policy were highly impacted and saw little benefits as a result. This has led to a massive distrust in future policy jumps by the federal government and combined with well-known policies such as the Jones Act. This act triggered protectionism, hurt Puerto Rican consumers, and also caused a rift between island elites and the federal government (Caraballo-Cueto. 2021) (Fuentes-Ramirez, Hosteler-Diaz, 2020).

As the island has been deindustrializing due to economic shortfalls and people fleeing, this has also led to leaders trying to use tax exemptions to try luring businesses in and trying to create demand for services by bringing new capital funding to the island (Espada, 2021). This has resulted in the islanders triggering massive protests against the policies, denouncing people from the mainland United States as invaders and a danger to their culture. This also followed an upsurge of populist rhetoric and backlash against expanding markets (Espada, 2021).

Here we can see how past policy failings, along with poverty, and people losing against past policy can trigger backlash to globalization or its concept. While there were benefits and a jumpstart to the economy, because governance failed to accommodate and help those affected, this caused people to feel alienated and become distrustful of globalization. When analyzing why people react negatively to shifts in global markets and opening markets, we must take cases like the one above into consideration to examine the impacts on those negatively affected.

Case Study: Protectionism in The United States

Protectionist sentiment is also important in trade and politics as firms, employers, and political institutions feel pressure to adopt protectionist policies in times of concern for the domestic economy. A primary example of modern backlash to globalization comes from US protectionist sentiment in response to China’s increasing influence and dominance as an economic superpower. At the core of this sentiment has been the concern for the loss of manufacturing jobs as they shift overseas to China and other such countries where labor is cheaper. The US manufacturing industry has experienced challenges from increased global competition and many Americans believe that outsourcing is resulting in unemployment and wage stagnation, especially in areas like the Rust Belt and red states experiencing industrial decline (Economist, 2023). The backlash against globalization was a major issue during the Trump administration during which the administration placed tariffs on billions of dollars worth of goods from around the world, especially from China (BBC, 2019). During his campaign, Trump argued protectionist policies would bring jobs back and reduce the trade deficit. This was an example of protectionist policies gaining traction in US economic policy. Such policies particularly found success under a Republican, right-wing, and conservative-leaning administration whose party has significant support from red states whose middle class has been losing in terms of economic geography. The tariffs placed on China during the Trump administration reflect an attempt to shield the US from foreign competition.

Another common way protectionism policies are promoted in the US government is through lobbying. Lobbying is a form of democratic participation where corporations and individuals can protect their interests and promote economic growth. Conservative states tend to lobby for protectionism in which communities vocalize their concerns over job security. There are concerns that the public trust in the political system is slowly eroding due to the potential for corruption and conflicts of interest. Despite these concerns, protectionist policies can safeguard domestic industries from unfair foreign competition, and measures such as tariffs and trade restrictions can address unfair practices. These protectionist policies are essential for national security and for reducing dependence on foreign countries, such as China, for strategic goods and therefore help maintain US national sovereignty. Prioritizing and protecting American jobs is supporting the interest of U.S. workers and globalization is threatening this. Outsourcing of U.S. jobs to foreign countries and economic inequality are damaging American national identity and the domestic economy (Aiden, 2022). American communities and industries continue to be disproportionately impacted by globalization and free trade and protectionist policies are a way for stakeholders to address these grievances. Lobbying, like tariffs, also helps threatened industries shield themselves from foreign competition. These are just some of the ways anti-globalization sentiments are expressed, particularly noteworthy as a major player in US politics.

Conclusion

Even though there are both proponents and adversaries on the topic of globalization, both parties can agree on the fact that globalization is an international phenomenon that has dominated the 21st century. The literature revolving around Globalization 1.0 (Pax Mongolica) and Globalization 2.0 (Pax Britannica) has been extensively covered and discussed but as the international community is currently experiencing Globalization 3.0, many citizens, government officials, and business owners are concerned as to how this new phase of globalization will affect their personal lives and the socio-economic conditions of their countries. Many have been sympathetic to the theories and beliefs of National Populism, wishing to protect their jobs against outsourcing to countries that have a cheaper labor force and increase the number of manufacturing jobs that have been lost due to globalization. And through an NNTT lens, as goods get cheaper and cheaper, the wages of low-skilled laborers will also decrease as their wages are directly affected by the products they help sell and create.

Globalization affects and shapes the economic conditions that people experience which in turn affects the political beliefs a person adopts. It is evident, with Puerto Rico being the prime example, that ideas of protectionism and national populism are appealing when it is evident that local and national job producers are being outsourced or taken by foreign markets. And as the gap between different economic classes grows, making clear distinctions between those who benefit from globalization and those who don’t, there will be a continued backlash against globalization. It is debatable as to whether the backlash against globalization will be successful in stopping its continued spread and growth and only time will tell if it ever succeeds.

References

Alden, E. (2022, May 10). The dangerous new anti-globalization consensus. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved April 18, 2023, from https://www.cfr.org/article/dangerous-new-anti-globalization-consensus

BBC. (2019, May 10). Trade wars, Trump tariffs and Protectionism explained. BBC News. Retrieved April 19, 2023, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-43512098

Beltekian, E. O.-O. and D. (2014). Trade and globalization. Our World in Data. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/trade-and-globalization

Breinlich, Ottaviano, G. I. ., & Temple, J. R. . (2014). Regional Growth and Regional Decline. In Handbook of Economic Growth (Vol. 2, pp. 683–779). Elsevier B.V. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53540-5.00004-5

Broz, J., Frieden, J., & Weymouth, S. (2021). Populism in Place: The Economic Geography of the Globalization Backlash. International Organization, 75(2), 464-494. doi:10.1017/S0020818320000314

Caraballo-Cueto. (2021). The Economy of Disasters? Puerto Rico Before and After Hurricane Maria. Centro Journal, 33(1), 66–.

Croteau, D., & Hoynes, W. (2014). Media/Society: Industries, images, and audiences (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

The Economist Newspaper. (2023, January 9). What America’s protectionist turn means for the world. The Economist. Retrieved April 19, 2023, from https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2023/01/09/what-americas-protectionist-turn-me ans-for-the-world

Eichengreen, B. J. (2020). The populist temptation: Economic grievance and political reaction in the modern era. Oxford University Press.

Espada, M. (2021, April 19). How Puerto Ricans are fighting back against using the island as a tax haven. Time. Retrieved April 20, 2022, from https://time.com/5955629/puertorico-tax-haven-opposition/

Flaherty, T., & Rogowski, R. (2021). Rising Inequality As a Threat to the Liberal International Order. International Organization, 75(2), 495-523. doi:10.1017/S0020818321000163

Fuentes-Ramírez. (2020). The Political Economy of Puerto Rico: Surplus Use and Class Structure. Latin American Perspectives, 47(3), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X20912529

Giddens, A. (2013). The Consequences of Modernity (1st ed.). Wiley. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1535427...-modernity-pdf (Original work published 2013)

Haskel, Lawrence, R. Z., Leamer, E. E., & Slaughter, M. J. (2012). Globalization and U.S. Wages: Modifying Classic Theory to Explain Recent Facts. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26(2), 119–139. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.26.2.119

Jones, B. (2018, May 10). Americans are generally positive about free trade agreements, more critical of tariff increases. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/05/10/americans-are-generally-positive-about-freetrade-agreements-more-critical-of-tariff-increases/

Krugman. (1991). Increasing Returns and Economic Geography. The Journal of Political Economy, 99(3), 483–499. https://doi.org/10.1086/261763

Krugman, & Venables, A. J. (1995). Globalization and the Inequality of Nations. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(4), 857–880. https://doi.org/10.2307/2946642

Lake, Martin, L. L., & Risse, T. (2021). Challenges to the Liberal Order: Reflections on International Organization. International Organization, 75(2), 225–257. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000636

Lang, M. (2006, December 1). Globalization and Its History. The Journal of Modern History, 78(4), 899-931. https://doi.org/10.1086/511251

Manuel Anselmi. (2017). Populism: An Introduction. Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315268392

Osland, J. S. (n.d.). Broadening the Debate: The Pros and Cons of Globalization. (2003). Eugene McDermott Library – The University of Texas at Dallas. Retrieved from https://journals sagepub-com.libproxy.utdallas.edu/doi/pdf/10.1177/1056492603012002005

Ottaviano, & Puga, D. (1998). Agglomeration in the Global Economy: A Survey of the “New Economic Geography.” World Economy, 21(6), 707–731. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9701.00160

Rommel, T., & Walter, S. (2018). The Electoral Consequences of Offshoring: How the Globalization of Production Shapes Party Preferences. Comparative Political Studies, 51(5), 621–658. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414017710264

Singh. (2021). Populism, Nationalism, and Nationalist Populism. Studies in Comparative International Development, 56(2), 250–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-021-09337-6

Stiglitz, J., & Pike, R. M. (2004). Globalization and its discontents. Canadian Journal of Sociology, 29(2), 321-324.

Stobierski, T. (2021, April 15). Effects of globalization on the environment. Business Insights Blog. Retrieved April 16, 2023, from https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/globalization-effects-on-environment#:~:text=Increased%20greenhous e%20gas%20emissions%2C%20ocean,reduce%20biodiversity%20around%20the%20globe.

Venida, V. S. (n.d.). (2000). The Economic Theory of Globalization. Eugene McDermott Library – The University of Texas at Dallas. From https://www-jstor-org.libproxy.utdallas.edu/stable/42634424?seq=1

Villanueva. (2021). Recovery work, life-work, and the extractive economies of finance capital in post-María Puerto Rico: A response to Beverley Mullings. Geoforum, 125, 107–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.07.008

Walter, S. (2021). The Backlash Against Globalization. Annual Review of Political Science, 24(1), 421–442. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102405